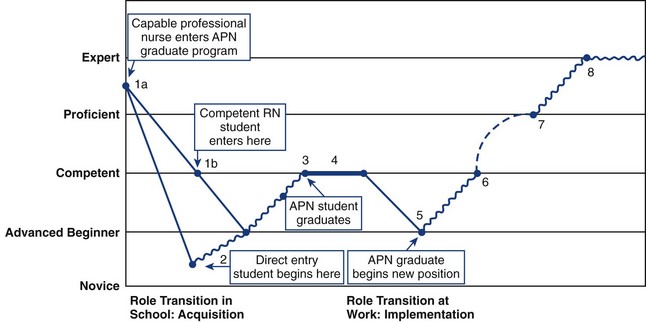

Chapter 4 Perspectives on Advanced Practice Nurse Role Development Novice to Expert Skill Acquisition Model Role Concepts and Role Development Issues Advanced Practice Nurse Role Acquisition in Graduate School Strategies to Facilitate Role Acquisition Advanced Practice Nursing Role Implementation at Work Strategies to Facilitate Role Implementation International Experiences with Advanced Practice Nurse Role Development and Implementation: Lessons Learned and a Proposed Model for Success Facilitators and Barriers in the Work Setting Continued Advanced Practice Nurse Role Evolution What is it like to become an advanced practice nurse (APN)? Role development in advanced practice nursing is described here as a process that evolves over time. The process is more than socializing and taking on a new role. It involves transforming one’s professional identity and the progressive development of the seven core advanced practice competencies (see Chapter 3). The scope of nursing practice has expanded and contracted in response to societal needs, political forces, and economic realities (Levy, 1968; Safriet, 1992; see Chapter 1). Historical evidence suggests that the expanded role of the 1970s was common nursing practice during the early 1900s (DeMaio, 1979). However, the core of nursing is not defined by the tasks nurses perform. This task-oriented perspective is inadequate and disregards the complex nature of nursing. In the current cost-constrained environment, the pressure to be cost-effective and to make an impact on outcomes is greater than ever, but studies have shown that the initial year of practice is one of transition (Brown & Olshansky, 1998; Brykczynski, 2009; Kelly & Mathews, 2001) and an APN’s maximum potential may not be realized until after approximately 5 or more years in practice (Cooper & Sparacino, 1990). This chapter explores the complex processes of APN role development, with the objectives of providing the following: (1) an understanding of related concepts and research; (2) anticipatory guidance for APN students; (3) role facilitation strategies for new APNs, APN preceptors, faculty, administrators, and interested colleagues; and (4) guidelines for continued role evolution. This chapter consolidates literature from all the APN specialties—including clinical nurse specialists (CNSs), nurse practitioners (NPs), certified nurse-midwives (CNMs), and certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNAs)—to present a generic process relevant to all APN roles. Some of this literature is foundational to understanding issues of role development for all APN roles and, although dated, remains relevant. This chapter has been expanded to include international APN role development experiences. Professional role development is a dynamic ongoing process that, once begun, spans a lifetime. The concept of graduation as commencement, whereby one’s career begins on completion of a degree, is central to understanding the evolving nature of professional roles in response to personal, professional, and societal demands (Gunn, 1998). Professional role development literature in nursing is abundant and complex, involving multiple component processes, including the following: (1) aspects of adult development; (2) development of clinical expertise; (3) modification of self-identity through initial socialization in school; (4) embodiment of ethical comportment (Benner, Sutphen, Leonard, & Day, 2010); (5) development and integration of professional role components; and (6) subsequent resocialization in the work setting. Similar to socialization for other professional roles, such as those of attorney, physician, teacher, and social worker, the process of becoming an APN involves aspects of adult development and professional socialization. The professional socialization process in advanced practice nursing involves identification with and acquisition of the behaviors and attitudes of the advanced practice group to which one aspires (Waugaman & Lu, 1999, p. 239). This includes learning the specialized language, skills, and knowledge of the particular APN group, internalizing its values and norms, and incorporating these into one’s professional nursing identity and other life roles (Cohen, 1981). Acquisition of knowledge and skill occurs in a progressive movement through the stages of performance from novice to expert, as described by Dreyfus and Dreyfus (1986, 2009), who studied diverse groups, including pilots, chess players, and adult learners of second languages. The skill acquisition model has broad applicability and can be used to understand many different skills better, ranging from playing a musical instrument to writing a research grant. The most widely known application of this model is Benner’s (1984) observational and interview study of clinical nursing practice situations from the perspective of new nurses and their preceptors in hospital nursing services. Although this study included several APNs, it did not specify a particular education level as a criterion for expertise. As noted in Chapter 3, there has been some confusion about this criterion. The skill acquisition model is a situation-based model, not a trait model. Therefore, the level of expertise is not an individual characteristic of a particular nurse but is a function of the nurse’s familiarity with a particular situation in combination with his or her educational background. This model could be used to study the level of expertise required for other aspects of advanced practice, including guidance and coaching, consultation, collaboration, evidence-based practice ethical decision making, and leadership (see Brykczynski [2009] for a detailed discussion of the Dreyfus model). Figure 4-1 shows a typical APN role development pattern in terms of this skill acquisition model. A major implication of the novice to expert model for advanced practice nursing is the claim that even experts can be expected to perform at lower skill levels when they enter new situations or positions. Hamric and Taylor’s report (1989) that an experienced CNS starting a new position experiences the same role development phases as a new graduate, only over a shorter period, supports this claim. FIG 4-1 Typical APN role development pattern. 1a, APN students may begin graduate school as proficient or expert nurses. 1b, Some enter as competent RNs, with limited practice experience. Depending on previous background, the new APN student will revert to novice level or advanced beginner level on assuming the student role. 2, A direct-entry APN student or NNCG student with no experience would begin the role transition process at the novice level. 3, The graduate from an APN program is competent as an APN student but has no experience as a practicing APN. 4, A limbo period is experienced while the APN graduate searches for a position and becomes certified. 5, The newly employed APN reverts to the advanced beginner level in the new APN position as the role trajectory begins again. The imposter phenomenon may be experienced here (Arena & Page, 1992; Brown & Olshansky, 1998). 6, Some individuals remain at the competent level. There is a discontinuous leap from the competent to the proficient level. 7, Proficiency develops only if there is sufficient commitment and involvement in practice along with embodiment of skills and knowledge. 8, Expertise is intuitive and situation-specific, meaning that not all situations will be managed expertly. See text for details. The overall trajectory expected during APN role development is shown in Figure 4-1; however, each APN experiences a unique pattern of role transitions and life transitions concurrently. For example, a professional nurse who functions as a mentor for new graduates may decide to pursue an advanced degree as an APN. As an APN graduate student, she or he will experience the challenges of acquiring a new role, the anxiety associated with learning new skills and practices, and the dependency of being a novice. At the same time, if this nurse continues to work as a registered nurse, his or her functioning in this work role will be at the competent, proficient, or expert level, depending on experience and the situation. On graduation, the new APN may experience a limbo period, during which the nurse is no longer a student and not yet an APN, while searching for a position and meeting certification requirements (see later). Once in a new APN position, this nurse may experience a return to the advanced beginner stage as he or she proceeds through the phases of role implementation. Even after making the transition to an APN role, progression in role implementation is not a linear process. As Figure 4-1 indicates, there are discontinuities, with movement back and forth as the trajectory begins again. Years later, the APN may decide to pursue yet another APN role. The processes of role acquisition, role implementation, and novice to expert skill development will again be experienced—although altered and informed by previous experiences—as the postgraduate student acquires additional skills and knowledge. Role development involves multiple, dynamic, and situational processes, with each new undertaking being characterized by passage through earlier transitional phases and with some movement back and forth, horizontally or vertically, as different career options are pursued. Direct-entry students who are non-nurse college graduates (NNCGs) and APN students with little or no experience as nurses before entry into an APN graduate program would be expected to begin their APN role development at the novice level (see Fig. 4-1). Some evidence indicates that although these inexperienced nurse students may lack the intuitive sense that comes with clinical experience, they avoid the role confusion associated with letting go of the traditional RN role commonly reported with experienced nurse students (Heitz, Steiner, & Burman, 2004). This finding has implications for APN education as the profession moves toward the Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) as the preferred educational pathway for APN preparation (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], 2006). Another significant implication of the Dreyfus model (Dreyfus & Dreyfus, 1986, 2009) for APNs is the observation that the quality of performance may deteriorate when performers are subjected to intense scrutiny, whether their own or that of someone else (Roberts, Tabloski, & Bova, 1997). The increased anxiety experienced by APN students during faculty on-site clinical evaluation visits or during videotaped testing of clinical performance in simulated situations is an example of responding to such intense scrutiny. A third implication of this skill acquisition model for APNs is the need to accrue experience in actual situations over time, so that practical and theoretical knowledge are refined, clarified, personalized, and embodied, forming an individualized repertoire of experience that guides advanced practice performance. As the profession encourages new nurses to move more rapidly into APN education, students, faculty, and educational programs must search for creative ways to incorporate the practical and theoretical knowledge necessary for advanced practice nursing. Discussing unfolding cases is a useful approach for teaching the clinical reasoning in transition so essential for clinical practice (Benner, Sutphen, Leonard, & Day, 2010; Day, Cooper, & Scott, 2012). This discussion of professional role issues incorporates role concepts described by Hardy and Hardy (1988) along with the concept that different APN roles represent different subcultural groups within the broader nursing culture (Leininger, 1994). Building on Johnson’s (1993) conclusion that NPs have three voices, Brykczynski (1999a) described APNs as tricultural and trilingual. They share background knowledge, practices, and skills of three cultures—biomedicine, mainstream nursing, and everyday life. They are fluent in the languages of biomedical science, nursing knowledge and skill, and everyday parlance. Some APNs (e.g., CNMs) are socialized into a fourth culture as well, that of midwifery. Others are also fluent in more than one everyday language. The concepts of role stress and strain discussed by Hardy and Hardy (1988) are useful for understanding the dynamics of role transitions (Table 4-1). Hardy and Hardy described role stress as a social structural condition in which role obligations are ambiguous, conflicting, incongruous, excessive, or unpredictable. Role strain is defined as the subjective feeling of frustration, tension, or anxiety experienced in response to role stress. The highly stressful nature of the nursing profession needs to be recognized as the background within which individuals seek advanced education to become APNs (Aiken, Clarke, Sloan, et al., 2002; Dionne-Proulz & Pepin, 1993). Role strain can be minimized by the identification of potential role stressors, development of coping strategies, and rehearsal of situations designed for application of those strategies. However, the difficulties experienced by neophytes in new positions cannot be eliminated. As noted, expertise is holistic, involving embodied perceptual skills (e.g., detecting qualitative distinctions in pulses or types of anxiety), shared background knowledge, and cognitive ability. A school-work, theory- practice, ideal-real gap will remain because of the nature of human skill acquisition. TABLE 4-1 Adapted from Hardy, M.E., & Hardy, W.L. (1988). Role stress and role strain. In M.E. Hardy & M.E. Conway (Eds.), Role theory: Perspectives for health professionals (pp. 159–239, 2nd ed.). Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange; and Schumacher, K.L., & Meleis, A.I. (1994). Transitions: A central concept in nursing. Image: The Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 26, 119–127. Bandura’s (1977) social cognitive theory of self-efficacy may be of interest to APNs in terms of understanding what motivates individuals to acquire skills and what builds confidence as skills are developed. Self-efficacy theory, a person’s belief in their ability to succeed, has been used widely to further understanding of skill acquisition with patients (Burglehaus, 1997; Clark & Dodge, 1999; Dalton & Blau, 1996). Self-efficacy theory has also been applied to mentoring APN students (Hayes, 2001) and training health care professionals in skill acquisition (Parle, Maguire, & Heaven, 1997). Role ambiguity (see Table 4-1) develops when there is a lack of clarity about expectations, a blurring of responsibilities, uncertainty regarding role implementation, and the inherent uncertainty of existent knowledge. According to Hardy and Hardy (1988), role ambiguity characterizes all professional positions. They have noted that role ambiguity might be positive in that it offers opportunities for creative possibilities. It can be expected to be more prominent in professions undergoing change, such as those in the health care field. Role ambiguity has been widely discussed in relation to the CNS role (Bryant-Lukosius, Carter, Kilpatrick, et al, 2010; Hamric, 2003; see also Chapter 14), but is also a relevant issue for other APN roles (Kelly & Mathews, 2001), particularly as APN roles evolve (Stahl & Myers, 2002). Role incongruity is intrarole conflict, which Hardy and Hardy (1988) described as developing from two sources. Incompatibility between skills and abilities and role obligations is one source of role incongruity. An example of this is an adult APN hired to work in an emergency department with a large percentage of pediatric patients. Such an APN will find it necessary to enroll in a family NP or pediatric NP program to gain the knowledge necessary to eliminate this role incongruity. This is a growing issue as NP roles become more specialized. Another source of role incongruity is incompatibility among personal values, self-concept, and expected role behaviors. An APN interested primarily in clinical practice may experience this incongruity if the position that she or he obtains requires performing administrative functions. An example comes from Banda’s (1985) study of psychiatric liaison CNSs in acute care hospitals and community health agencies. She reported that they viewed consultation and teaching as their major functions, whereas research and administrative activities produced role incongruity. APNs experience intraprofessional role conflict for a variety of reasons. The historical development of APN roles has been fraught with conflict and controversy in nursing education and nursing organizations, particularly for CNMs (Varney, 1987), NPs (Ford, 1982), and CRNAs (Gunn, 1991; see also Chapter 1). Relationships among these APN groups and nursing as a discipline have improved markedly in recent years, but difficulties remain (Fawcett, Newman, & McAllister, 2004). The degree to which APN roles demonstrate a holistic nursing orientation as opposed to a more disease-specific medical orientation remains problematic (see value-added discussion under collaboration, later). Communication difficulties that underlie intraprofessional role conflict occur in four major areas: (1) at an organizational level; (2) in educational programs; (3) in the literature; and (4) in direct clinical practice. Kimbro (1978) initially described these communication difficulties in reference to CNMs, but they are relevant for all APN roles. The fact that CNSs, NPs, CNMs, and CRNAs each have specific organizations with different certification requirements, competencies, and curricula creates boundaries and sets up the need for formal lines of communication. Communication gaps occur in education when courses and textbooks are not shared among APN programs, even when more than one specialty is offered in the same school. Specialty-specific journals are another formal communication barrier because APNs may read primarily within their own specialty and not keep abreast of larger APN issues. In clinical settings, some APNs may be more concerned with providing direct clinical care to individual patients, whereas staff nurses and other APNs may be more concerned with 24-hour coverage and smooth functioning of the unit or institution. These differences may set the stage for intraprofessional role conflict. During the 1980s and 1990s, when there was more confusion about the delineation of roles and responsibilities between RNs and NPs, RNs would sometimes demonstrate resistance to NPs by refusing to take vital signs, obtain blood samples, or perform other support functions for patients of NPs (Brykczynski, 1985; Hupcey, 1993; Lurie, 1981), and they were not admonished by their supervisors for these negative behaviors. These behaviors are suggestive of horizontal violence (a form of hostility), which may be more common during nursing shortages (Thomas, 2003). Roberts (1983) first described horizontal violence among nurses as oppressed group behavior wherein nurses who were doubly oppressed as women and as nurses demonstrated hostility toward their own less powerful group, instead of toward the more powerful oppressors. Recognizing that intraprofessional conflict among nurses is similar to oppressed group behavior can be useful in the development of strategies to overcome these difficulties (Bartholomew, 2006; Brykczynski, 1997; Farrell, 2001; Freshwater, 2000; Roberts, 1996; Rounds, 1997; see Chapter 11). According to Rounds (1997), horizontal violence is less common among NPs as a group than among RNs generally. Over the years, as the NP role has become more accepted by nurses, there appear to be fewer cases of these hostile passive-aggressive behaviors, often currently referred to as bullying, toward NPs. However, they are still reported in APN transition literature (Heitz et al., 2004; Kelly & Mathews, 2001). One way to address these issues would be to include APN position descriptions in staff nurse orientation programs. Curry’s claim (1994) that thorough orientation of staff nurses to the APN role, including clear guidelines and policies regarding responsibility issues, is an important component of successful integration of NP practice in an emergency department setting is also applicable to other roles and settings. Another significant strategy for minimizing intraprofessional role conflict is for the new APN, and APN students, to spend time getting to know the nursing staff to establish rapport and learn as much as possible about the new setting from those who really know what is going on—the nurses. This action affirms the value and significance of nurses and nursing and sets up a positive atmosphere for collegiality and intraprofessional role cooperation and collaboration. In Kelly and Mathews’ study (2001) of new NP graduates, such a strategy was exactly what new NPs regretted not having incorporated into their first positions. One way to promote positive interprofessional relationships is to provide education and practice experiences that include APN students, medical students, and both physician and APN faculty to enhance mutual understanding of both professional roles (Kelly & Mathews, 2001). Developing such interprofessional education (IPE) experiences is difficult because of different academic calendars and clinical schedules. However, these obstacles can be overcome if these interdisciplinary activities are considered essential for improved health care delivery and if they have sufficient administrative support. Some programs attempt to overcome these scheduling issues by mandating IPE for APNs while it remains an elective experience for medical students, thereby reinforcing an optional and not important perspective among medical students. The issues of professional territoriality and physician concern about being replaced by APNs were reported by Lindblad and colleagues (2010) from an ethnographic study of the first four APNs to graduate in 2005 from the first CNS program in Sweden. The APNs and general practitioners (GPs) agreed that the usefulness of the APNs would have been greater if the APNs had been able to prescribe medications and order treatments. After working with the APNs, the GPs saw them more as an additional resource and complement rather than a threat. By 2009, there were 16 APNs working in the new role in primary health care. Further clarification and definition of APN role responsibilities and collaboration will be forthcoming from Sweden. The complementary nature of advanced practice nursing to medical care is a foreign concept for some physicians, who view all health care as an extension of medical care and see APNs simply as physician extenders. This misunderstanding of advanced practice nursing underlies physicians’ opposition to independent roles for nurses because they believe that APNs want to practice medicine without a license (see Chapters 1 and 3). In fact, numerous earlier studies of APN practice have demonstrated that advanced practice roles incorporate a holistic approach that blends elements of nursing and medicine (Brown, 1992; Brykczynski, 1999a, b; Fiandt, 2002; Grando, 1998; Johnson, 1993). However, when APNs are viewed by physicians as direct competitors, it is understandable that some physicians would be reluctant to be involved in assisting with APN education (National Commission on Nurse Anesthesia Education, 1990). In addition, some nurse educators have believed that physicians should not be involved in teaching or acting as preceptors for APNs. Improved relationships between APNs and physicians will require redefinition of the situation by both groups. The Interprofessional Education Collaborative’s (IPEC, 2011) advocacy for an interprofessional vision for all health professionals and the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM, 2003) recommendation that the health professional workforce be prepared to work in interdisciplinary teams underscore the imperative of interprofessional collaboration (see Chapter 12). Competency in interprofessional collaboration is critical for APNs because it is central to APN practice. This content is incorporated into the leadership and interprofessional partnership components of The Essentials of Doctoral Education for Advanced Nursing Practice (AACN, 2006). Some interesting research has recently emerged on this issue in Canada and Europe. A participatory action research study conducted in British Columbia, Canada (Burgess & Purkis, 2010) indicated that NPs viewed collaboration as both a philosophy and a practice. “They cultivated collaborative relations with clients, colleagues, and health care leaders to address concerns of role autonomy and role clarity, extend holistic client-centered care and team capacity, and create strategic alliances to promote innovation and system change” (p. 300). Of particular importance is the fact that the NP participants described themselves as being nurses first and practitioners second. This is significant because when role emphasis is on physician replacement and support rather than on the patient-centered, health-focused, holistic nursing orientation to practice, the nursing components of the role become less valued and invisible (Bryant-Lukosius, DiCenso, Browne, & Pinelli, 2004). Medically driven and illness-oriented health systems tend to devalue these value-added components of APN roles and reimbursement mechanisms for including these aspects of care are lacking. Fleming and Carberry (2011) reported on a grounded theory study of expert critical care nurses transitioning to the role of APN in an intensive care unit (ICU) setting in Scotland. Initial perceptions were that the APN role was closely aligned with medical practice, but later perceptions supported earlier studies that the APN role was characterized by an integrated, holistic, patient-centered approach to care, which was close to the medical model, but different because it was carried out within an expert nursing knowledge base. They identified that further research is needed to explore the outcomes of this integrated practice. This is the research imperative for APNs—to demonstrate the impact of the holistic nursing approach to care on patient outcomes. Nurse-midwives have been in the forefront of developing collaborative relationships with physicians for many years. All APN groups would benefit from attention to the progress that CNMs have made in collaboration with physicians. The joint practice statement of the American College of Nurse Midwives (ACNM) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) can be used as a model for other APN groups (ACOG/ACNM, 2011). It highlights key principles for improving communication, working relationships, and seamlessness in the provision of women’s health services (see also the ACNM’s website, www.acnm.org). Problems with previous joint practice statements were that they included varying interpretations of physician supervision. According to the most recent statement, “OB-GYNs and CNMs/CMs are experts in their respective fields of practice and are educated, trained, and licensed, independent providers who may collaborate with each other based on the needs of their patients. Quality of care is enhanced by collegial relationships characterized by mutual respect and trust, as well as professional responsibility and accountability” (ACOG/ACNM, 2011). Role transitions are defined here as dynamic processes of change that occur over time as new roles are acquired (see Table 4-1). Five essential factors influence role transitions (Schumacher & Meleis, 1994): (1) personal meaning of the transition, which relates to the degree of identity crisis experienced; (2) degree of planning, which involves the time and energy devoted to anticipating the change; (3) environmental barriers and supports, which refer to family, peer, school, and other components; (4) level of knowledge and skill, which relates to prior experience and school experiences; and (5) expectations, which are related to such factors as role models, literature, and media. The role strain experienced by individuals in response to role insufficiency (see Table 4-1 for definitions) that accompanies the transition to APN roles can be minimized, although certainly not completely prevented, by individualized assessment of these five essential factors, development of strategies to cope with them, and rehearsal of situations designed for application of these strategies. Entering graduate school may be associated with a ripple effect of concurrent role transitions in family, work, and other social arenas (Klaich, 1990). The personal meaning of role transitions was a major focus of literature in nursing role development in the United States from the 1970s through 2005. This topic is currently more prevalent in the international APN literature as APN roles are being established in different countries. In a review of APN role development literature from certificate and graduate NP programs, alterations in self-identity and self-concept emerged as a consistent theme, with role acquisition experiences commonly described as identity crises (see Brykczynski [1996] for a detailed discussion of this earlier work). In their study of NP students, Roberts and colleagues (1997) reported findings similar to those observed decades earlier by Anderson, Leonard, and Yates (1974). Anderson and colleagues described the process of role development observed in three NP programs (a graduate program, post-baccalaureate certificate program, and continuing education program), whereas Roberts and associates described a current graduate NP program. Anderson and colleagues’ (1974) description of NP students’ progression from dependence to interdependence being accompanied by regression, anxiety, and conflict was found to be similar to observations made by Roberts and coworkers (1997) in graduate NP students over a period of 6 years (Table 4-2). For many years, my NP faculty colleagues and I have observed similar role transition processes in teaching role and clinical courses for graduate NP students. In a discussion of role transition experiences for neonatal NPs, Cusson and Viggiano (2002) made the important point that even positive transitions are stressful. TABLE 4-2 Role Acquisition Process in School Adapted from Anderson, E.M., Leonard, B.J., & Yates, J.A. (1974). Epigenesis of the nurse practitioner role. American Journal of Nursing, 10, 12–16; and Roberts, S.J., Tabloski, P., & Bova, C. (1997). Epigenesis of the nurse practitioner role revisited. Journal of Nursing Education, 36, 67–73. Roberts and colleagues (1997) observed 100 NP graduate students and reviewed their student clinical journals. They identified three major areas of transition as students progressed from dependence to interdependence: (1) development of professional competence; (2) change in role identity; and (3) evolving relationships with preceptors and faculty. The lowest level of competence coincided with the highest level of role confusion. This occurred at the end of the first semester and the beginning of the second semester in the three-semester program examined (Roberts et al., 1997). The most intense transition period seemed to come at the end of the students’ first clinical immersion experience. Roberts and colleagues (1997) described the first transition as involving an initial feeling of loss of confidence and competence accompanied by anxiety (see Table 4-2, stage I). Initial clinical experiences were associated with the desire to observe, rather than provide care, the inability to recall simple facts, the omission of essential data from history taking, feelings of awkwardness with patients, and difficulty prioritizing data. The students’ focus at this time was almost exclusively on acquiring and refining assessment skills and continued development of physical examination techniques. By the end of the first semester, students reported returning feelings of confidence and the regaining of their former competence in interpersonal skills. Although they were still tentative about diagnostic and treatment decisions, students reported feeling more comfortable with patients as some of their basic nursing abilities began to return (see Table 4-2, stage II). Transitions in nursing role identity occurring during the first two stages were associated with feelings of role confusion. Students were dismayed at how slowly and inefficiently they were performing in clinical situations and reported feelings of self-doubt and lack of confidence in their abilities to function in the real world of health care. They sought shortcuts in attempts to increase their efficiency. They reported profound feelings of responsibility regarding diagnostic and treatment decisions and, at the same time, increasingly realized the limitations of clinical practice when they were confronted with the real-life situations of their patients. They recalled finding it easy to second-guess physicians’ decisions in their previous nursing roles, but now they found those decisions more problematic when they were responsible for making them. They joked about feeling like adolescents. This is the point that Cusson and Viggiano (2002) were making when they commented, in reference to neonatal NPs, that the infant really does look different when viewed from the head of the bed rather than the side of the bed. They explained that “rather than taking orders, as they did as staff nurses, neonatal NPs must synthesize incredibly complex information and decide on a plan of action. Experienced neonatal nurses often guide house staff regarding care decisions and writing orders to match the care that is being given. However, the shift in responsibility to actually writing the orders can be very intimidating” (p. 24). Roberts and colleagues (1997) observed that a blending of the APN student and the former nurse developed during stage II as students renewed their appreciation for their previous interpersonal skills as teachers, supporters, and collaborators and again perceived their patients as unique individuals in the context of their life situations. Students developed increased awareness of the uncertainty involved in the process of making definitive diagnostic and treatment decisions. In spite of current attempts to reduce diagnostic and treatment uncertainty through evidence-based practice, a basic degree of uncertainty is still inherent in clinical practice. Although these insights served to demystify the clinical diagnostic process, the students’ anxiety about providing care increased. Learning about strategies to cope with clinical decision making in situations of uncertainty, such as ruling out the worst case scenario, seeking consultation, and monitoring patients closely with phone calls and follow-up visits, can decrease anxiety and promote increased confidence (Brykczynski, 1991). The transition in the relationships between students and preceptors and students and faculty in the study by Roberts and colleagues (1997) involved students feeling anxious that they were not learning enough and would never know enough to practice competently. Students felt frustrated and perceived that faculty and preceptors were not providing them with all the information they needed. During the third stage (see Table 4-2), as they felt more confident and competent, students began to question the clinical judgments of their preceptors and faculty. This process is thought to help students advance from independence to interdependence—the last stage of the transition process. Much of the conflict at this juncture appeared to derive from students’ feelings of “ambivalence about giving up dependence on external authorities” (Roberts et al., 1997, p. 71) such as preceptors and faculty and assuming responsibility for making independent judgments based on their own assessments from their clinical and educational experiences and the literature. The relevance of these role acquisition processes for other APN roles has not been reported. This is another area in which research would be helpful. Until recently, the literature on APN role acquisition in school has focused exclusively on individuals who were already nurses. A commonly held assumption among nurses is “the more clinical experience, the better” for acquiring the necessary knowledge and skill to take on complex APN roles. At least 1 year of nursing practice is typically preferred for admission to APN programs. The process of role acquisition for students in direct-entry APN master’s programs that admit NNCGs may differ because these individuals were not functioning as nurses before they entered the program. For additional information regarding this topic, see the qualitative study reported by Rich and Rodriguez (2002). In their qualitative study of family nurse practitioner (FNP) role transition, Heitz and colleagues (2004) found differences in role acquisition experiences between FNP students who were inexperienced nurses and FNP students who were experienced nurses. Feelings of insecurity, inadequacy, vulnerability, and being overwhelmed were typical, but role confusion was reported primarily by the more experienced RN students as they went through the letting go process of the RN role and taking on the FNP role. It will be interesting to observe whether this finding holds true for BSN to DNP students.

Role Development of the Advanced Practice Nurse

Perspectives on Advanced Practice Nurse Role Development

Novice to Expert Skill Acquisition Model

Note: Refer to the Dreyfus skill acquisition model for further details (Benner, 1984; Benner, Tanner, & Chesla, 2009; Dreyfus & Dreyfus, 1986; 2009). For the purpose of illustration, this figure is more linear than the individualized role development trajectories that actually occur.

Role Concepts and Role Development Issues

![]()

Concept

Definition

Examples

Role stress

A situation of increased role performance demand

Returning to school while maintaining work and family responsibilities

Role strain

Subjective feeling of frustration, tension, or anxiety in response to role stress

Feeling of decreased self-esteem when performance is below expectations of self or significant others

Role stressors

Factors that produce role stress

Financial, personal, or academic demands and role expectations that are ambiguous, conflicting, excessive, or unpredictable

Role ambiguity

Unclear expectations, diffuse responsibilities, uncertainty about subroles

Some degree of ambiguity in all professional positions because of the evolving nature of roles and expansion of skills and knowledge

Role incongruity

A role with incompatibility between skills and abilities and role obligations or between personal values, self-concept, and role obligations

An adult NP in a role requiring pediatric skills and knowledge

Role conflict

Occurs when role expectations are perceived to be mutually exclusive or contradictory

Role conflict between APNs and other nurses and between APNs and physicians

Role transition

A dynamic process of change over time as new roles are acquired

Changing from a staff nurse role to an APN role

Role insufficiency

Feeling inadequate to meet role demands

New APN graduate experiencing the imposter phenomenon (Arena & Page, 1992; Brown & Olshansky, 1998)

Role supplementation

Anticipatory socialization

Role-specific educational components in a graduate program

Role Ambiguity

Role Incongruity

Role Conflict

Intraprofessional Role Conflict

Interprofessional Role Conflict

Role Transitions

Advanced Practice Nurse Role Acquisition in Graduate School

![]()

Stage

Definition

Descriptive Features

I

Complete dependence

Immersion in learning medical components of care; role transition associated with role confusion and anxiety; decreased appreciation for psychosocial components of health and illness concerns; loss of confidence in clinical skills; feelings of incompetence

II

Developing competence

Ongoing clinical preceptorship experiences; didactic classes that incorporate medical diagnostic and nursing and medical therapeutic components, along with personal experience of illness components; renewed sense of appreciation for the value of nursing knowledge and skills; more realistic self-expectations of clinical performance, although still uncomfortable about accountability; increased confidence in ability to succeed in learning and making a valid contribution to care; initial formation of own philosophy and standards of practice

III

Independence

Comfortable with ability to conduct holistic assessments (physical and psychosocial); concentration on intervention and management options; conflicts with preceptors as student and preceptor challenge one another; conflicts with faculty relate to management options, clinical evaluations, examination questions, concern over not being taught all there is to know

IV

Interdependence

Renewed appreciation for interdependence of nursing and medicine; development of individualized version of advanced practice role

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access