Chapter 11. Using communication tools in health promotion practice

Chapter Contents

Guidelines for selecting and producing health promotion resources147

The range of health promotion resources: uses, advantages and limitations149

Producing health promotion resources150

Presenting statistical information151

Using mass media in health promotion153

Using the Internet for health promotion159

Summary

The first part of this chapter offers some principles governing the choice of communication tools and a summary of the uses, advantages and limitations of the main types of health promotion resources. There are guidelines for making the most of display materials, for producing written materials (including guidance on nonsexist writing) and for presenting statistical information. This is followed by a section on mass media, including identifying the key characteristics of mass media, the variety of ways in which mass media are channels for health promotion, what mass media can be expected to achieve and how they can be used effectively. Guidelines are given for working with radio, television and local press. There is a case study on the use of mass media advertising, and exercises on writing plain English, preparing and presenting material on television and radio, writing a press release and writing a letter to the editor. The chapter ends with a section on using information technology for health promotion.

The range of communication tools outlined in Table 11.1 are used extensively by health promoters but may not always be employed with maximum effectiveness. How communication tools are selected and used is as crucial as the quality of the resources themselves.

| TYPE OF RESOURCE | USES AND ADVANTAGES | LIMITATIONS |

|---|---|---|

| Leaflets and handouts | Clients can use at their own pace and discuss with other people. Educator and client can work through together. Can be easy and cheap to produce basic written information. Can reinforce points in a talk and add further detailed information | Commercially produced leaflets can be expensive and may contain advertising. Mass-produced leaflets are not tailored to everyone’s needs. Not durable, easily lost. Mass distribution can be wasteful |

| Posters and display charts | Can raise awareness of issues. Can convey information and direct people to other sources (addresses, tel. numbers, ‘pick up a leaflet’). Simple posters and information displays can be cheap to produce | High quality is expensive to make or buy. Get tatty quickly unless laminated. Need to ensure any writing is big enough to be read at the distance most people will see it Displays need changing frequently to attract attention |

| Whiteboards | Good for building up information, explaining particular points. Cheap, reusable | Educator needs to turn back to audience to write on board. Image too small for large groups |

| Flip-charts | Good for brainstorming and involving groups in producing ideas which can be stuck up round the room for discussion. Useful for recording notes to be written up later. Can be prepared in advance. Useful where no whiteboard available | Educator needs to turn back to audience to write on board. Flip-chart paper easily torn and dog eared |

| DVDs | Can be used to convey real situations otherwise inaccessible (e.g. childbirth), convey information, pose problems, demonstrate skills, trigger discussion on attitudes and behaviour. Can be used for self-teaching. Can be stopped, started or replayed to allow discussion | Normal TV-size screen too small for large audiences. Educator relies on equipment working properly. Equipment expensive and not easily transported. May need partially darkened room |

| PowerPoint presentation | Useful in large rooms or lecture theatres with a big screen. Complex information (such as graphs) can be seen clearly | Needs equipment and screen, and blackout |

| CDs | Good for certain skills development, e.g. relaxation, exercise routines. Equipment cheap, easy to use and transport | Lack of visual material requires extra concentration to hold attention |

| Health websites | Websites have the potential of reaching a worldwide audience and are useful for raising awareness of health issues, conveying information and delivering self-help materials | There is an enormous amount of health information that can be accessed on the Internet and no control over the quality |

Guidelines for Selecting and Producing Health Promotion Resources

There is a huge range of material available, with a constant turnover as items become out of date or out of print and new ones come on the market. You could find yourself with the task of selecting a leaflet, poster, display or DVD from a range of possibilities. Or you may find that there is very little available, and you have to decide whether the one item you have found is suitable.

The guidelines are designed to help you select any kind of material, such as leaflets or audiovisual, and you can also use them as a checklist when producing your own.

Is it appropriate for achieving your aims?

Think about the item in the context in which you intend to use it. For example, if you are working with a group of young smokers who are not motivated to stop, a leaflet or video on how to stop smoking is unlikely to be helpful. Materials to trigger discussion with the aim of challenging attitudes might be better.

See Chapter 14, section on stages of change model.

Is it the most appropriate kind of resource?

Will something else be cheaper and just as effective, such as photographs instead of a DVD? Could you use the real thing, such as parents in person talking about their experiences of a new baby instead of a DVD; actual food instead of pictures or models?

Is it consistent with your values and approach?

If your approach is to work in a nonjudgemental partnership with your clients, the materials you use should reflect your values. You need to avoid material that is patronising, authoritarian, scaremongering or victim-blaming. Resources should not attribute or imply blame to individuals experiencing ill health when that ill health is rooted in their socioeconomic circumstances, for example low income or poor housing.

See section on exploring relationships with clients in Chapter 10.

Is it relevant for your clients?

Does it take account of the values, culture, health concerns, age, ethnic group, sex and socioeconomic circumstances of your clients? Does it reflect local practice and health services available?

Obvious examples of irrelevance are DVDs portraying lifestyles of affluent middle-class families, which are unhelpful if you are working with people in the UK who have limited financial resources. Materials designed for one ethnic group may not be appropriate for another, not just because of language but because some aspects (such as sexual behaviour or attitudes to bereavement) are seen differently in different cultures.

Is it racist or sexist?

All resources should be nonracist and nonsexist. Racist materials stereotype people, attributing certain roles or character attributes based on ethnic group alone. Implicit in this are the assumptions that one ethnic group is superior to another and represents the desired norm. (See Robinson 2002 for information on communicating with ethnic groups.)

Sexist materials stereotype gender roles, behaviours or character attributes. Resources should also not make assumptions about sexual orientation. Guidance on nonsexist writing is provided later in this chapter.

Resources should reflect the fact that we live in a multiracial society where the roles of men and women have changed and continue to do so. Strong, positive messages and images should be provided of people of all ethnic groups and both sexes.

Will it be understood?

Is it written in plain English, which people will readily understand? Are there any incorrect assumptions about the level of literacy or existing knowledge? Does it need to be produced in other languages, to make it accessible to people from minority ethnic groups? Do leaflets need to be produced in other formats so that they are accessible to people with disabilities, such as in large type or Braille, or for DVDs, for example, with sign language or subtitles inserted on the screen?

Is the information reliable?

Is information in the materials accurate, up to date, unbiased and complete? Or does it contain one-sided information on controversial issues, and out-of-date or incomplete messages?

Does it contain advertising?

Commercial companies such as drug companies, baby food manufacturers or makers of safety equipment who produce material will produce leaflets and posters that will carry the name of the company or its products, or include advertisements. Using these resources can imply that you (or your employer) are endorsing the product. It may also damage your image as a credible source of unbiased health information, and lead people to doubt the value of the information.

For these reasons, resources containing company names, products and advertising should be avoided whenever possible. However, the item may be just what you want, and there may be no alternative. In which case:

• The product or service advertised must be ethically acceptable as healthy and environmentally friendly. This excludes tobacco, alcohol and confectionery advertising, for example.

• The advertising content must be low key. The company name on the front or back cover is acceptable, but constant references to named-brand products are not.

The Range of Health Promotion Resources: Uses, Advantages and Limitations

Table 11.1 summarises the wide range of resources available for health promotion and the key points about their uses, advantages and limitations. It is also important to note:

• Resources are aids, and should generally not be seen as substitutes for the health promoter. Leaflets should be used in conjunction with face-to-face discussion. DVDs are best presented with an introduction and a follow-up discussion.

• It takes time and practice to become familiar with using all the health promotion resources available.

See the section on health promotion teaching and learning in Chapter 12.

Producing Health Promotion Resources

Most resources, particularly posters, leaflets and audiovisual materials, come ready made, but you might want to work with a community group to help them to produce materials that target their particular need, or produce some yourself.

See also Chapter 10, section on written communication, and Chapter 12, section on improving patient communication.

This chapter does not offer a comprehensive guide on how to produce materials, but approaching the task in a systematic way using the planning and evaluation flowchart in Chapter 5 may be helpful. If you are producing a resource such as a health promotion leaflet, you will need to consider who will write the draft, who will edit it, whether and how to pilot the draft, what it will cost and whether you need the services of a desktop publisher, designer, illustrator, translator or printer.

Making the most of display materials: posters, charts, display boards and stands

Be brief and to the point

Keep the objective firmly in mind. Do not include material that is irrelevant; it will only distract from the main message.

Emphasis the key point(s)

Use size of lettering, style or colour to achieve this. Place the important messages just above the centre of a display, which is the point of maximum visual impact.

Use language the audience understands

Explain any unfamiliar technical terms. If possible, express the message in both pictures and words. Test it out on a few people to ensure that you have no unexpected ambiguities in your message.

Be bold

Words and pictures should be as large as possible.

Make the most of colour

Colour can create continuity; for example, a repetition of background colour can link a series of posters. Colour can be used to identify parts of a diagram or highlight important information. Choose colours with care, because responses to colour are emotional (for example, green is soothing), and because colours may be associated with certain messages, images and places (such as red for danger, purple for funerals, white for clinical cleanliness).

Improve the display site

If all you have is a blank wall or a wall covered with distracting wallpaper, fix a rectangle of coloured card to the wall as a background display board. If a display board has a rough or marked surface, give it a coat of paint or a covering of coloured paper, hessian or felt.

Use the display site to best advantage

Busy corridors can only be useful sites for posters with immediate appeal and few words. More information can be conveyed in a waiting area, and it may be possible to supplement displays with leaflets to take away. Ensure that writing on displays is at eye level and large enough to read without people having to move from the queue or their chair.

Be aware of lighting

Daylight is unreliable; spotlights directed onto a display are ideal.

Making the most of written materials: instruction sheets and cards, leaflets and booklets

Pilot materials on a sample of consumers

Do not assume that you know what they like, want or need: ask them.

Use colour, layout and print size to improve clarity

Larger print may be helpful for those people with a visual impairment.

Use plain English

Use everyday words; avoid jargon and explain any technical or medical words. Aim for short sentences of 15–20 words. Use active rather than passive verbs,: for example, say ‘Increase your fruit and vegetable consumption …’ rather than ‘Your fruit and vegetable consumption should be increased …’. Undertake Exercise 11.1 to practise plain English.

EXERCISE 11.1

Writing plain English

Write plain English versions of the following. The first three are very similar to the instructions found on the packages of medication bought over the counter in chemist shops. The last three are very similar to passages in health promotion leaflets.

1. Wheezoff paediatric syrup is specially formulated for children. It is indicated for the relief of cough and its congestive symptoms and for the treatment of hay fever and other allergic conditions affecting the upper respiratory tract. Contraindications, warnings, etc. Hypersensitivity to any of the active constituents. If symptoms persist consult your doctor.

2. Notwinge cream – directions for use. Apply a sufficient quantity of balm to the part affected. Massage lightly until penetration is complete.

3. The baby lies curled up in what is called the fetal position. It lies in a bag of water and the membranes which make up this fluid-filled balloon are enclosed in the womb.

4. Vitamin B1, also called thiamin, is required for the functioning of the nervous system, digestion and metabolism. Insufficient vitamin B1 can cause anorexia and fatigue.

Do a readability test on your written materials

Many word-processing packages are able to give readability statistics as well as the average sentence length and the percentage of passive sentences used. They give a rough measure of readability for adult readers based on the principle that the combination of long sentences and long words is harder to comprehend. But note that many other factors that affect readability are not taken into account, such as how the text is laid out, the use of illustrations and the size of print.

Nonsexist Writing

The importance of material being nonracist and nonsexist has already been discussed, but using language in a nonsexist way presents particular challenges. One is the use of ‘man’ as a generic term for a person. For example, people talk about manning an exhibition stand when it is just as likely to be staffed by a woman. Many job titles end with ‘man’ and date from the time when only men performed these duties, for example postman.

Another problem is the generic use of the male pronoun. For example, ‘Each doctor presented a case from his own practice’, assumes that all the doctors are men. Although it may seem clumsy to say ‘he’ or ‘she’, it can sometimes usefully emphasis that both sexes are involved. An alternative which has been used in this book is to turn the singular into a plural and use the words ‘they’ or ‘their’: changing ‘A health promoter must be a fluent communicator. He must also be a good listener.’ To ‘Health promoters must be fluent communicators. They must also be good listeners.’

It may be possible to rephrase a passage to eliminate the pronouns altogether. So, instead of ‘Information given to a social work agency is confidential in the same way as communications between a doctor and his patients’, say ‘… in the same way as communications between doctors and patients’.

Another way is to use ‘you’ instead of ‘he’, ‘she’ or a noun that implies male or female. For example, in a leaflet on parenting, you could change ‘A mother often finds difficulty in persuading her 2-year-old to eat’ to ‘You may find difficulty in persuading your 2-year-old to eat’ or ‘Parents may find difficulty …’ This avoids the implication that only mothers (not fathers) have a parenting role.

Or avoid ‘he’ by finding another noun. Thus, in ‘You may find it difficult to persuade your 2-year-old to eat. He may prefer throwing his food around instead’ you could say ‘… A child at this age may prefer throwing food around instead.’

It is also important to avoid sexism when speaking as well as writing. So, for instance, a health promoter who refers to the women who attend a smoking cessation programme as ‘the ladies’ could affront the women in the group. It is far better to refer to the women who attend as ‘patients’ or ‘clients’.

For further discussion of language barriers, see the section on overcoming language barriers in Chapter 10.

Presenting Statistical Information

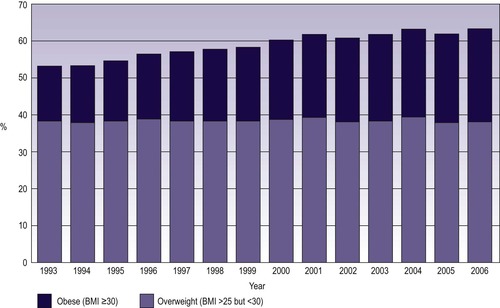

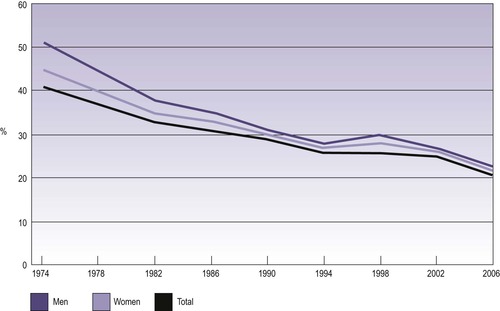

Numbers may be meaningless to lay people unless they are carefully presented in a visual way, such as in Figs 11.1 and 11.2. A wide range of computer software programmes facilitates the production of information in ways that are visually arresting and easy to understand. NHS organisations and local authorities are likely to have the equipment and expertise to support this production and there are Internet sites which also contain statistics reproduced visually. See, for example, the NHS Information Centre (http://www.ic.nhs.uk).

|

| Fig. 11.1 Proportion of the adult population overweight and obese. (Source: General Household Survey, Office of National Statistics (reproduced inBlack 2008: 40)). |

|

| Fig. 11.2 Proportion of the adult population who smoke. (Source: Health Survey for England (reproduced inBlack 2008: 38)). |

Using Mass Media in Health Promotion

The mass media are channels of communication to large numbers of people and include television, radio, the Internet, magazines and newspapers, books, displays and exhibitions. Leaflets and posters are also mass media when they are used on a stand-alone basis, as opposed to use as a learning aid in face-to-face communication with an individual or a group. However, usually when people talk about the media they are referring to television, radio, newspapers and magazines.

Health promoters are most likely to become involved with mass media when undertaking health promotion programmes or campaigns with the public, or when a public health issue becomes a news item. Probably most involvement will be with local newspapers and local radio or television. However, it is useful to put this into a wider context, and to appreciate the range of ways in which health issues and messages are portrayed via mass media.

Mass Media as Tools for Health Promotion

Health messages and information are sent through the mass media in a number of different ways:

• Planned, deliberate health promotion, from posters and leaflets, displays and exhibitions on health themes, such as all of the mass media resources available for Change4life campaign, a society-wide movement that aims to prevent people from becoming overweight by encouraging them to eat a healthy diet and take more exercise (Department of Health (DoH) 2009a), to advertisements and campaigns on television, such as the Worried campaign based on teenagers’ worries about their parents smoking (DoH 2009b) and in newspapers (see, for example, Martinson & Hindman 2005).

• Health promotion by advertisers and manufacturers of healthy products and services: for example the Safety In The Sun leaflet produced by Boots the Chemist helped convey the SunSmart message by providing information for customers (Cancer Research UK 2005).

• Books, television, newspapers and magazine articles about health issues which follow new research disseminated in academic conferences or journals or government publications. The problem here is that the media may distort the evidence with attention-grabbing headlines which can give out unhealthy messages, such as the example in Box 11.1.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access