Chapter 5. Planning and evaluating health promotion

Summary

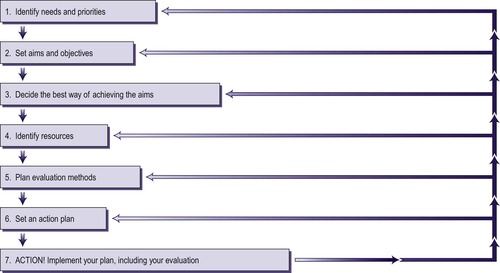

This chapter presents an outline of a planning and evaluation cycle for use in the everyday work of health promoters. It involves seven stages which include the measurement and specification of needs and priorities; the setting of aims and objectives; decisions on the best way of achieving aims; the identification of resources; the planning of evaluation methods and the establishment of an action plan followed by action. Examples are given of aims, objectives and action plans, and exercises are provided on setting aims and objectives and using the planning framework to turn ideas into action.

This chapter is about planning and evaluation at the level of your daily work in health promotion. It provides a basic framework for you to use to plan and evaluate your health promotion activities, whether you work with clients on a one-to-one or group basis, or undertake specific projects or programmes.

The Planning Process

Planning is a process that, at its very simplest, should give you the answers to three questions:

1. What am I trying to achieve? This question is concerned with identifying needs and priorities, then with being clear about your specific aims and objectives.

2. What am I going to do? This can be helpfully broken down into smaller steps:

– Select the best approach to achieving your aims.

– Identify the resources you are going to use.

– Set a clear action plan of who does what and when.

3. How will I know whether I have been successful? This question highlights the importance of evaluation and the integral part it plays in planning health promotion interventions. It should not be an afterthought or left too late to capture the information you need.

The planning process has been put together in the seven-stage flowchart in Fig. 5.1. The arrows on the flowchart lead you round in a circle. This is because, as you carry out your plan and evaluation, you will probably find things that make you re-think and change your original ideas. For example, things you might want to change could include: working on a need you found you had overlooked; scaling down your objectives because they were too ambitious; or changing the educational or publicity materials because you found that they were not as useful or effective as you had hoped. The direction of the arrows is anticlockwise, but in reality planning is not always an orderly process. You may actually start at Stage 6, with a basic idea of a health promotion intervention. Thinking more about it may lead you to clarify exactly what your aims are (Stage 2). Next, you might think about what resources you are going to need (Stage 4) and realise that you do not have enough time or money to do what you had in mind, so you go back to Stage 2 and modify your aims. Then you think about the best way of achieving your aims (Stage 3) and work out an action plan (Stage 6). After that, you start to think seriously about how you will know whether you are successful (Stage 5) and you put your evaluation plans into your action plan (Stage 6 again). In effect, you are continually reviewing and improving your plan, using the framework appropriately to help you keep on course.

|

| Fig. 5.1 A flowchart for planning and evaluating health promotion. |

Planning takes place at many levels. If you are embarking on a major project, you will need to take time to plan it in depth and detail. If you are simply planning a short one-to-one session with a client you will still need to plan, and to go through all the stages, but the process might be quick and may not even be written down.

For example, a chiropodist seeing a patient with a foot care problem may identify that the patient needs knowledge and skills in cutting toenails correctly. They decide that their aim is to give the patient basic information and training on this. They will know if they have been successful by getting feedback from the patient about how they managed next time they see them. They identify an information leaflet that they can give the patient as reinforcement. They decide on an action plan of explanation, demonstration and then get the patient to practise. They review the patient’s toenail cutting skills next time they see them, reinforcing or correcting as necessary. All this planning takes place inside the chiropodist’s head, and is an integral part of their everyday professional practice.

The Planning Framework

Stage 1: Identify Needs and Priorities

How do you find out what health promotion is needed? If you think you already know, what are you basing your judgement on? Who has identified the need: you, your clients or someone else? Identifying need is a complex process, which is looked at it in depth in the next chapter.

See Chapter 6.

You may have a long list of health promotion needs you would like to respond to, so another issue is how to establish your priorities. Again, this is discussed in detail in the next chapter, but an important point is that you must have a clear view about which needs you are responding to, and what your priorities are.

Stage 2: Set Aims and Objectives

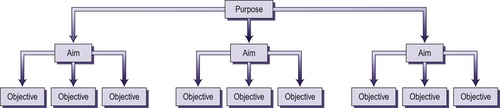

People use a range of words to describe statements about what they are trying to achieve, such as aims, objectives, targets, goals, mission, purpose, result, product, outcomes. It can be helpful to think of them as forming a hierarchy as in Fig. 5.2. At the top of the hierarchy are words that tell you why your job exists, such as your job purpose or remit, or your overall mission. In the middle of the hierarchy are words that describe what you are trying to do in general terms, such as your goals or aims. At the bottom of the hierarchy are words that describe in specific detail what you are trying to do, such as targets or objectives.

|

| Fig. 5.2 A hierarchy of aims. |

It is worth noting that objectives can be of different kinds. Health objectives are usually expressed as the outcome or end state to be achieved in terms of health status, such as reduced rates of illness or death. However, in health promotion work objectives are often expressed in terms of a step along the way towards an ultimate improvement in the health of individuals or populations, such as increasing exercise levels.

In health education work, educational objectives are framed in terms of the knowledge, attitudes or behaviour to be exhibited by the learner. Objectives can also be in terms of other kinds of changes, for example a change in health policy (introducing a healthy eating policy in the workplace) or health promotion practice (providing health information in minority ethnic languages).

See the section below on setting educational objectives.

The term target is increasingly used in health promotion. Targets usually specify how the achievement of an objective will be measured, in terms of quantity, quality and time (the date by which the objective will be achieved). So a health target can be defined as a measurable improvement in health status, by a given date, which achieves a health objective. This is the approach used in national strategies for health, such as Choosing Health: Making Healthier Choices Easier (Department of Health (DoH) 2004) and in the National service frameworks (http://www.dh.gov.uk). An example of targets and ways of measuring progress can be found in the Delivering Choosing Health: Making Healthier Choices Easier (DoH 2005).

There is more about national strategies and targets in Chapter 7, section on national public health strategies.

The objectives are framed as health objectives, and the targets are framed as health targets (changes in rates of death or illness by a specific date), behaviour targets (such as changes in population rates of smoking or drinking by a specific date) or progress measures (such as the number of people attending a smoking cessation service and the number setting a date when they plan to stop smoking).

When you plan health promotion initiatives, you need to set aims, objectives and targets or goals and outcomes.

Your aims (or aim, as there does not have to be more than one) are broad statements of what you are trying to achieve. Your objectives are much more specific, and setting these is a critical stage in the planning process.

Objectives are the desired end state (or result, or outcome) to be achieved within a specified time period. They are not tasks or activities. Objectives should be as follows:

• Challenging. The objective should provide you with a health promotion challenge in relation to what needs to be achieved.

• Attainable. On the other hand, it should be both realistic and achievable within the constraints of your situation.

• Relevant. It should be consistent with the aims of the organisation and with the overall aims of your job.

• Measurable. You should try to identify objectives that are measurable, for example specifying quantity, quality and a time when they will be achieved. For instance (using the example in Exercise 5.1), an objective of ‘to improve access to health information through the use of videos…’ has been improved by working out the appropriate number of videos and languages, and then specifying the target as ‘to have ten videos in six languages…’

EXERCISE 5.1

Clarifying your purpose, aims and objectives

Read this example of a health promoter’s purpose, aims and objectives.

Mark is a health promoter working for a local authority. His purpose is to reduce inequalities in health in the population living and working in the borough. To do this, one of his aims is to improve levels of health knowledge of the black and ethnic minority groups. One of his objectives is to improve access to health information through the use of videos. He sets a target of having a selection of ten health videos in six languages available in 25 shops within 4 months.

Now:

1. Thinking of your own job, write down what you believe to be its mission or purpose.

2. Then give an example of one of the health promotion aims you are trying to achieve.

3. Finally, give an example of an objective you are trying to achieve, in fulfillment of the aim you selected.

If you can’t find an example from your practice, make up an example of what you would like to do if you had the opportunity.

It is sometimes difficult to distinguish between aims, objectives and action plans. For example, a dietician who wants to improve the information they give to patients may describe their aim as ‘to produce an information leaflet’ but this is also their objective and their action plan. The answer is to think it through further, and ask ‘Why produce a leaflet? What am I aiming to achieve by producing the leaflet?’ It then becomes clearer that the aim is to improve patient compliance with dietary treatment, and one of the objectives is to improve patients’ understanding of their dietary instructions. The action is to produce the leaflet. The importance of actually thinking through your aims and objectives in this way is that it helps you to be absolutely clear about why you are doing something, not just what you are doing. Failure to think through this stage means that health promoters waste time and energy proceeding with what seems like a good idea only to realise, too late, that what they are doing is not actually achieving what they want.

Setting educational objectives

If your health promotion activity is based on a health education approach, it is useful to plan in terms of educational objectives.

Educationalists traditionally often think of objectives (sometimes called learning outcomes) in terms of what the clients will gain. Furthermore, the objectives are considered to be of three kinds: what the educator would like the clients to know, feel and do as a result of the education. In the language of the educationalist, these may be referred to as cognitive, affective and behavioural objectives.

Objectives about ‘knowing’

These are concerned with giving information, explaining it, ensuring that the client understands it, and thus increasing the client’s knowledge: for example, explaining the weight loss advantages of increasing exercise levels to someone who is obese. Here the objective would be to develop in the client an understanding of the value of exercise with regard to their weight loss programme to enable them to make informed choices in terms of their weight loss strategies.

Objectives about ‘feeling’

These objectives are concerned with attitudes, beliefs, values and opinions. These are complex psychological concepts, but the important feature to note now is that they are all concerned with how people feel. Objectives about feelings are about clarifying, forming or changing attitudes, beliefs, values or opinions. In the example above, when the health promoter is educating a client about exercise and weight loss, in addition to the knowledge objective, there may be an objective about helping the client to explore their attitude towards exercise and any values, beliefs or opinions that might be forming a barrier to increasing exercise levels.

Objectives about ‘doing’

These objectives are concerned with a client’s skills and actions. For example, teaching a routine of aerobic or yoga exercises has the objective that clients acquire practical skills and are able to do exercise-related specific tasks.

In the health education approach to health promotion, a combination of the knowing, feeling or doing educational objectives is usually required. For example, when a health visitor is advising a parent about feeding their toddler, they may be planning to achieve the following objectives within three home visits:

• The objective of ensuring that the parent knows which foods constitute a healthy eating programme for their child and which are best given in restricted amounts.

• The objective of changing the parent’s erroneous belief that sugar is essential to give their child energy, and relieving their anxiety that their healthy child’s food fads may cause serious ill health.

• The objective that the parent learns what to do at meal times when her child has a tantrum about eating.

To summarise the key points about setting aims and objectives:

• The focus is on what you are trying to achieve.

• Be as specific as possible. Avoid vague or subjective notions of what you want to achieve.

• Express your objectives in ways that can be measured. How much? How many? When?

• Do not get bogged down in terminology. It does not matter whether you talk about goals, aims, objectives, targets or outcomes. The key principle is to be very clear about what you are trying to achieve.

In order to practise setting aims and objectives, undertake Exercise 5.1 and Exercise 5.2.

EXERCISE 5.2

Setting aims and objectives

Yewtree scheme

The three practices at Yewtree Health Centre have agreed to establish physical activity assessment sessions, backed up by a display in the shared waiting area, with the aim of reducing the incidence of coronary heart disease in the practice populations.

The detailed objectives are:

1. To raise the users’ awareness of the link between inadequate exercise and coronary heart disease, and the part which individuals can play in reducing their own vulnerability to the disease.

2. To assess, and advise about, individuals’ physical fitness levels and help them to prepare an appropriate exercise action programme based on those results.

3. To monitor and evaluate, on a continuing basis, the effectiveness of the fitness testing, in respect of the resources involved and the reduction in vulnerability to heart disease.

Ask yourself the following questions:

1. Do the objectives match the characteristics of objectives described above? Are they challenging, attainable, as measurable as possible and relevant?

2. How would you suggest changing the objectives?

Stage 3: Decide the Best Way of Achieving the Aims

Occasionally, there might be only one possible way of accomplishing your aims and objectives. Usually, however, there will be a range of options. In Case study 5.1 Jim has a number of options about how to achieve his objective of increasing the sun safety measures being taken by the school and the children. He could write to the schools or to parents of school-age children, he could hand out leaflets at school gates, he could lobby parents to take up the cause, he could find out if there are any school governors’ meetings and ask to speak at them, he could conduct a sun safety campaign in the local media, he could write an article on the issue of sun safety in school playgrounds for the education journals that teachers read, or he could try to meet each Head Teacher face-to-face. Or he could do two or more of these together.

CASE STUDY 5.1

Jim is an environmental health officer. His project is to tackle sun safety in schools. This fits in with the overall purpose of his job, which is to ensure safer environments. Jim works out that his aim is to work with local schools to set up a scheme that will result in sun safety measures being taken by the school and the children. He researches the subject in detail, looking at the results achieved from similar projects and working out how much time and money it is likely to take. He then decides that it is reasonable to set his objective as follows:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access