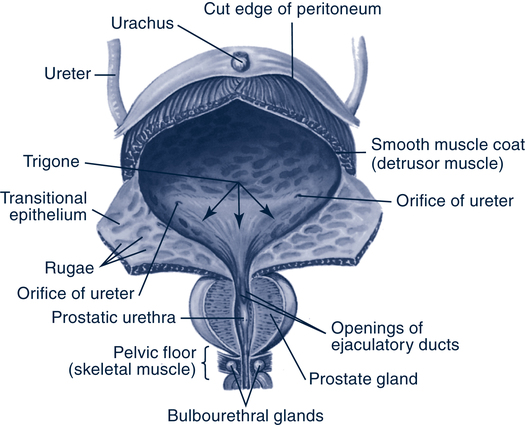

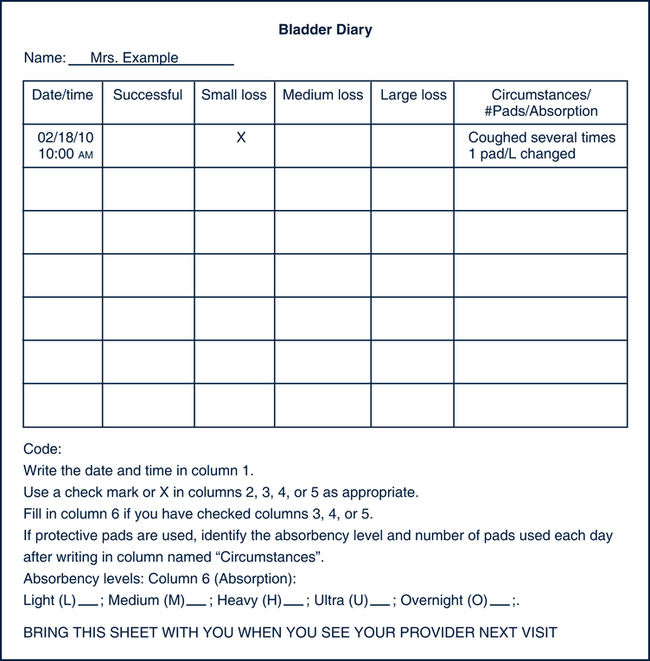

Sabrina Friedman, MSN, PhD, EdD, FNP, CNS On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Describe how aging affects normal bladder function. 2. List four possible causes of acute incontinence. 3. List the types of persistent incontinence and their clinical characteristics. 4. List the components of a continence history. 5. Discuss the role of functional and environmental assessment in the evaluation of urinary incontinence. 6. Discuss how the nurse can use tests of provocation in making a nursing diagnosis of clients with urinary incontinence. 7. Describe the behavioral interventions used to treat urinary incontinence in cognitively intact clients. 8. Develop a client teaching plan for a client with urge incontinence. 9. Develop a caregiver teaching plan for a client with functional urinary incontinence resulting from dementia. 10. Describe the effects of normal aging on renal function. 11. Identify the possible causes of acute and chronic renal failure. 12. Identify the treatment options for clients with bladder cancer. 13. List supportive services for the individual who has undergone a cystectomy. 14. Differentiate between benign prostatic hypertrophy and prostate cancer. 15. Identify the treatment options for clients with prostate cancer. 16. Apply the nursing process in the care of older adults with select urinary system conditions. Contrary to the belief of many older adults and even some health care providers, aging is not the sole cause of UI. However, aging does affect the lower urinary tract (Fig. 28–1). These age-related changes increase an older adult’s susceptibility to other insults to the lower urinary tract. As a result, these insults (e.g., drug side effects, UTIs, and conditions impairing mobility) are more likely to produce incontinence in older clients than in younger ones. UI is very common in the older adult, especially among older women and is underrecognized (Halter et al, 2009). UI is even more common among nursing facility residents. Affecting slightly more than half of all nursing facility residents, UI is an independent predictor for nursing facility admission and is associated with irritant dermatitis, pressure ulcers, falls, significant sleep interruptions, and UTIs (Halter et al, 2009). Many health care providers do not ask clients about incontinence. Even when clients inform them about incontinence, many providers ignore the problem and do not provide adequate diagnosis and treatment. Screening for urinary incontinence has increasingly become recognized as an indicator of quality of care (Halter et al, 2009) UI is generally classified as either acute (transient) or chronic (persistent). Acute incontinence has a sudden onset, is generally associated with some medical or surgical condition, and generally resolves when the underlying cause is corrected (Ouslander, 2003) (Box 28–1). Medication is a common cause and should always be suspected as a potential cause of new incontinence. Although the exact prevalence of acute incontinence is not known, any new onset of incontinence should be considered acute, and possible precipitating causes should be ruled out. Addressing the cause has the potential to resolve the incontinence. Persistent incontinence is not related to an acute illness. It continues over time, often becoming worse. Major types of persistent incontinence include stress, urge, overflow, and functional incontinence (Agency for Health Care Policy and Research [AHCPR], 1996; Dash et al, 2004). These types of incontinence can occur in combination, causing mixed incontinence. Stress incontinence is commonly seen in older women, who involuntarily lose urine as the result of a sudden increase in intraabdominal pressure. Stress incontinence occurs as pressure in the bladder (intravesical pressure) exceeds urethral resistance when intraabdominal pressure increases in the absence of a detrusor (bladder) contraction. This can be caused by a lack of estrogen, obesity, previous vaginal deliveries, and/or surgeries (Halter et al, 2009). Individuals with stress incontinence often leak urine with physical exertion such as coughing, sneezing, laughing, lifting, and exercise. Older women may report leakage when they change position (e.g., get out of a chair) or lift a small child. These activities increase intraabdominal pressure, which increases bladder pressure. If the urethra, supporting tissues, and bladder neck are abnormal, urethral resistance may be too low to withstand the increased pressure on the bladder, which results in involuntary urine loss. Stress incontinence is unusual in men, and it mainly occurs after transurethral surgery for benign conditions or after surgery or radiation therapy for lower urinary tract malignancy when the anatomic sphincters are damaged (Halter et al, 2009). Urge incontinence is also common in the older adult population. Urge incontinence is usually, although not always, associated with abnormal detrusor contractions (AHCPR, 1996; Dash et al, 2004). Common causes of urge incontinence include local genitourinary conditions such as cystitis, urethritis, tumors, stones, and diverticula, as well as central nervous system disorders such as stroke, dementia, and Parkinson’s disease (Ouslander, 2003). Individuals with urge incontinence typically give a history of involuntary urine loss after a sudden urge to void. Urgency and involuntary urine loss can be precipitated by the sound of running water, cold weather, or the sight of a toilet. Urinary accidents are sometimes large. Urge incontinence is often accompanied by nocturia and complaints of frequency. Urge incontinence can be classified as one of the following types, based on etiology and the bladder abnormality (AHCPR, 1996): 1. Detrusor hyperreflexia (DH), when the uninhibited bladder (detrusor) contractions are caused by a neurologic problem (e.g., stroke). 2. Detrusor instability (DI), when there is no underlying neurologic problem. 3. Detrusor sphincter dyssynergia (DSD), when the uninhibited bladder contraction is accompanied by contraction of the external sphincter. This results in urinary retention and may be seen in clients with suprasacral spinal cord lesions and multiple sclerosis. 4. Detrusor hyperactivity with impaired bladder contractility (DHIC), when uninhibited bladder contractions are accompanied by impaired contractility during voluntary voiding. As a result, the client must strain to empty his or her bladder either completely or incompletely. This type of urge incontinence may be seen in frail older adults. Overflow incontinence occurs when a chronically full bladder increases bladder pressure to a level higher than urethral resistance, causing the involuntary loss of urine. On the basis of the history alone, overflow incontinence may be difficult to differentiate from stress or urge incontinence. It accounts for only a small number of incontinence cases in older adults. Typically, individuals with overflow incontinence complain of frequent loss of small volumes of urine. They may have both daytime and nighttime accidents. Overflow incontinence can occur as a result of an atonic bladder that does not contract adequately (e.g., from diabetic neuropathy, anticholinergic medications, or spinal cord injury); a mechanical obstruction to bladder emptying (e.g., prostatic hypertrophy, a large cystocele, or uterine prolapse); or dyssynergia, a condition in which the urethral sphincter contracts during bladder contraction, preventing the bladder from emptying (e.g., from multiple sclerosis) (AHCPR, 1996). The purpose of the diagnostic evaluation for UI is threefold (Ouslander, 2003): 1. To identify potentially reversible factors that may be contributing to the incontinence 2. To identify clients who need more than a basic evaluation 3. To determine the type of incontinence so that appropriate treatment can be initiated The basic evaluation for UI includes a history, physical examination, postvoid residual (PVR) testing, and urinalysis. This evaluation is indicated for all clients with incontinence and is often sufficient for diagnosing the type of incontinence and for guiding therapy (AHCPR, 1996). A PVR result over 100 mL may indicate inadequate bladder emptying. A clean urine specimen should be collected for urinalysis. If there is a delay in processing a urine specimen, it should be refrigerated. During the incontinence history assessment, the following information should be collected: • The onset of the incontinence • The frequency and volume of accidents • The circumstances that cause urine loss, including (1) any leaking of urine when the client coughs, sneezes, laughs, changes positions, climbs steps, exercises, has an urge to void, hears running water, is cold, or is sleeping, (2) any involuntary urine loss caused by caffeine, alcohol, or any medication, and (3) whether the client leaks urine without being aware that it occurred, has any postvoid dribbling, or leaks continuously • Bladder habits, including the frequency and volume of daytime and nighttime urination • Daily fluid intake, including caffeine intake • Self-management techniques the client uses to manage the incontinence (e.g., frequent voiding, restricting the volume or type of fluid, incontinence products, urine collection devices) • Previous evaluation and treatment of the incontinence, including the client’s perception of the effectiveness of previous treatment measures • Any other urinary tract symptoms, including urgency, burning, pain, hematuria, weakness of the urinary stream, intermittent stream, and difficulty emptying the bladder completely • Bowel habits, including constipation, laxative use, and fecal incontinence Because function problems often contribute to UI, functional assessment is one of the most important parts of the evaluation. Information should be collected about the client’s ability to perform normal activities of daily living (ADLs), including grooming, dressing, getting in and out of bed, and walking. Clients who have difficulty performing these ADLs often have difficulty toileting. Functional status can be assessed by unstructured questioning or by using a structured questionnaire such as the Older Americans Research and Service Center Instrument (OARS) (Duke University Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development, 1978) or the Katz Index of ADLs (Katz et al, 1963) (see Chapter 4). Direct observation provides the most valuable information about the client’s mobility and toileting ability. The following observational guide can be used in practice (Burgio & Goode, 1997): 1. Place the client 15 feet from the toilet. 2. Ask the client to approach the toilet, either on foot or in a wheelchair, and to prepare and position for voiding. 3. Note the time it takes the client to reach the toilet and any difficulty in getting undressed or positioning for voiding. 4. If the client is unable to toilet independently and a caregiver normally assists the client, observe the toileting procedure with caregiver assistance. Mental status should be assessed during the functional assessment. Cognitive ability can affect the client’s ability to recognize the need to urinate, locate the toilet, and undress for toileting. In addition, knowledge of a client’s cognitive status is essential in planning nursing interventions for incontinence. The most efficient way to assess cognitive status is to use a standardized instrument such as the Folstein MiniMental State Examination (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975) (see Chapter 4). • Any barriers between the client’s usual location and the toilet, such as poor lighting, steps, furniture, or other objects • The size of the bathroom: is it large enough to accommodate the client and any assistive devices (wheelchair or walker) that must be used? • Toilet height: is it adequate or too high or low? • Presence of grab bars, if needed • Availability of caregiver or nursing staff assistance, if needed The physical examination should include • Inspection of gait and balance • Neurologic assessment of any weakness, paralysis, or sensory deficit in the lower extremities, which can affect a client’s ability to toilet • Abdominal examination for bladder distention, suprapubic tenderness (occurs in bladder infections), and costovertebral angle tenderness (occurs in kidney infections) • Rectal examination for fecal impaction; rectal sensation and tone; and, for men, the size, shape, and consistency of the prostate gland • Measurements of sitting and standing blood pressure to detect orthostatic hypotension and dizziness • Pelvic examination, including inspection of the vagina for atrophic changes, vaginitis, cystocele, rectocele, or uterine prolapse 1. Ask the client to cough 3 or 4 times while in a supine position. 2. Ask the client to stand; note any involuntary urine loss during the position change. 3. Ask the client to cough 3 or 4 times while standing. 4. If the client’s physical condition permits, ask him or her to bounce on the heels 3 or 4 times. 5. Have the client listen to running water. 6. Ask the client to walk to the bathroom. One of the most effective ways to assess bladder habits is to ask the client or caregiver to keep a diary of the frequency of urination and any incontinent episodes, their relative volume, and the circumstances that precipitated their occurrence (e.g., coughing, sneezing, urgency, and changing position). Fig. 28–2 shows a sample bladder diary. Bladder diaries can be used in the home, hospital, or nursing facility and can be kept by the client or caregiver. They provide a more objective and accurate measure of a client’s bladder habits than can be obtained by recall alone. They can be especially useful for a client who has short-term memory problems. If they are to be accurate, however, clients and caregivers need careful instructions on their maintenance. History: The client reports leaking urine with activities that increase intraabdominal pressure (e.g., coughing, sneezing, laughing, lifting, position changes, walking, climbing steps, or exercise). Objective observations: Leaking urine with stress provocation; signs of pelvic floor relaxation (e.g., cystocele, rectocele, or uterine prolapse) observed on pelvic examination Bladder records: Documentation of urine loss during physical activities that increase intraabdominal pressure History: The client reports a sudden urge to void, followed by involuntary urine loss; the client may also report that running water or cold weather precipitates involuntary urine loss. Objective observations: Leaking urine with urge provocation Bladder records: Documentation of urine loss associated with urgency; frequent urination and nocturia also frequently recorded History: Client histories vary, but they often show frequent involuntary urine loss of small amounts. Urine loss may be associated with physical exertion. Complaints may include decreased force of the urine stream, hesitancy, a feeling of incomplete bladder emptying, and frequent urination of small amounts of urine. Clients may also have risk factors for urinary retention, such as diabetes or the use of anticholinergic medications. Objective observations: An elevated PVR (greater than 100 mL) is the hallmark of overflow incontinence. This should be part of the initial evaluation of clients with UI. On abdominal examination a distended bladder may be detected on percussion or palpation. In cases in which overflow incontinence is related to prostatic hypertrophy, an enlarged prostate can be detected on rectal examination. In women a large cystocele observed during pelvic examination may suggest the cause of overflow incontinence. Bladder records: Documentation of frequent small-volume urinary accidents History: The client or caregiver reports large-volume urine loss in places other than the toilet, commode, bedpan, or urinal in the absence of symptoms of stress, urge, or overflow incontinence. The client may be unaware of the need to void or have significant mobility impairment. Objective observations: In pure functional incontinence, leaking is not seen with stress or urge provocation and the PVR result is normal. A mental status examination may reveal cognitive impairment. Functional assessment may reveal impaired mobility and toileting skills. Bladder records: Documentation of involuntary urine loss (often large accidents) without symptoms of urge or stress incontinence Nursing interventions for UI focus on behavioral therapies. In 1988 the National Institutes of Health (NIH) held a consensus conference to review the status of knowledge on UI. The conference stated, “As a general rule, the least invasive or least dangerous procedures should be tried first. For many forms of incontinence, behavioral techniques meet this criterion” (NIH Consensus Development Conference, 1990). Despite the effectiveness of these techniques, many nurses are not skilled in their implementation. The most appropriate behavioral intervention depends on the type of incontinence and a client’s cognitive status (Du Moulin et al, 2005). Pelvic floor muscle exercises were first reported as a treatment for UI by Kegel (1948). These exercises consist of alternating contraction and relaxation of the levator ani muscles, which are the muscles of the pelvic floor. These muscles, including the pubococcygeal muscle surrounding the midportion of the urethra, contract as a unit. In older adults these muscles are often weak from disuse atrophy. Performed correctly, pelvic floor muscle exercises strengthen the muscles, increase urethral resistance, and allow the client to use the muscles voluntarily to prevent urinary accidents (Wyman, 2003). Clinicians often use verbal feedback during digital examination of the rectum or vagina to help clients identify their pelvic floor muscles. The nurse inserts two fingers into the vagina or one into the rectum and asks the client to contract the pelvic floor muscles. Approximately one third of clients are correctly able to identify and contract their pelvic floor muscles on digital examination and can use this exercise as a successful intervention for UI. The majority of older clients, however, need additional help in identifying and learning to use their pelvic floor muscles. These clients often benefit from pelvic floor muscle biofeedback. Biofeedback is not a treatment in itself, but if appropriately used, it can facilitate acquisition of the ability to contract and use the pelvic floor muscles to prevent involuntary urine loss (Burgio & Goode, 1997). During biofeedback, the client is given immediate auditory and/or visual feedback of pelvic floor muscle contractions. After training with biofeedback or verbal feedback, the client must practice pelvic floor muscle exercises at home. The client should be instructed to practice contracting and relaxing the pelvic floor muscles at least 45 times a day, in three or four practice sessions. The client should exercise lying down, sitting, and standing. This facilitates the client’s ability to identify and use the muscles in any position. The nurse should remind the client to relax the abdominal muscles when exercising as this is essential for successful performance of exercises. The nurse can ask clients to try occasionally to slow or stop their urine stream while voiding. This allows them to monitor their progress in using and strengthening the correct muscles (Box 28–2). Once clients master the exercises, they should be taught strategies to prevent involuntary urine loss (stress and urge strategies). Clients with stress accidents should be instructed to contract their pelvic floor muscles before and during activities that precipitate leaking such as coughing, sneezing, lifting, or changing position. Those with urge incontinence can be taught to contract their pelvic floor muscles to inhibit involuntary bladder contractions. A client should respond to an urge to void by relaxing and contracting the pelvic floor muscles three or four times quickly. When the urgency subsides, the client should walk to the toilet at a normal pace (Box 28–3).

Urinary Function

Age-Related Changes in Structure and Function

Prevalence of Urinary Incontinence

Myths and Attitudes

Common Problems and Conditions

Acute Incontinence

Chronic Incontinence

Stress Incontinence

Urge Incontinence

Overflow Incontinence

Diagnosis of Urinary Incontinence

Nursing Management

![]() Assessment

Assessment

History

Functional Assessment

Environmental Assessment

Physical Examination

Tests of Provocation

Bladder Habits

![]() Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Stress Incontinence

Urge Incontinence

Overflow Incontinence

Functional Incontinence

![]() Intervention

Intervention

Cognitively Intact Clients

Pelvic Floor Muscle Exercises

Urinary Function

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access