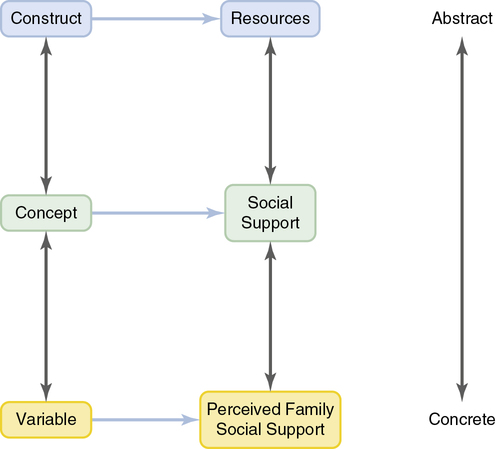

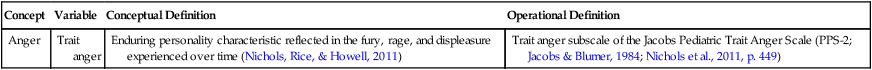

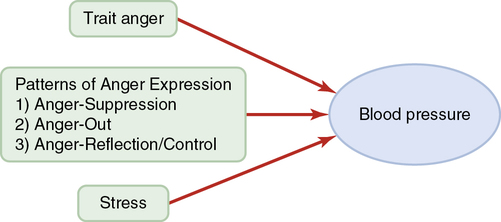

After completing this chapter, you should be able to: 1. Define theory and the elements of theory (concepts, relational statements, and propositions). 2. Distinguish between the levels of theoretical thinking. 3. Describe the use of middle range theories as frameworks for studies. 4. Describe the purpose of a study framework. 5. Identify study frameworks developed from nursing theories. Theories are the ideas and knowledge of science. In a psychology course, you may have studied theories of the mind, defense mechanisms, and cognitive development that provide explanations of thinking and behavior. In nursing, we also have theories that provide explanations, but our theories explain human responses to illness and other phenomena important to clinical practice. For example, nursing has a theory of using music and movement to improve health outcomes (Murrock & Higgins, 2009). A theory of adaptation to chronic pain (Dunn, 2004, 2005) has also been developed, as well as a theory of unpleasant symptoms (Lenz, Pugh, Milligan, Gift, & Suppe, 1997). With the increased focus on quality and safety (Sherwood & Barnsteiner, 2012), a theory has been developed to describe a culture of safety in a hospital (Groves, Meisenbach, & Scott-Cawiezell, 2011). Theories guide nurses in clinical practice and in conducting research. As a researcher develops a plan for conducting a quantitative study, the theory on which the study is based is expressed as the framework for the study. A study framework is a brief explanation of a theory or those portions of a theory that are to be tested in a study. The major ideas of the study, called concepts, are included in the framework. The framework with the concepts and their connections to each other may be described in words or in a diagram. When the study is conducted, the researcher can then answer the question, “Was this theory correct in its description of reality?” Thus a study tests the accuracy of theoretical ideas proposed in the theory. In explaining the study findings, the researcher will interpret those findings in relation to the theory (Grove, Burns, & Gray, 2013). Qualitative studies may be based on a theory or may be designed to create a theory. Because the assumptions and underlying philosophy of qualitative research (see Chapter 3) are not the same as quantitative research, the focus of this chapter is on theory as related to quantitative studies. To assist you in learning about theories and their use in research, the elements of theory are described, types of theories are identified, and how theories provide frameworks for studies are discussed. You may notice that references in this chapter are older, because we cited primary sources for the theories, many of which were developed 10 or more years ago. You are also provided with guidelines for critically appraising study frameworks, and these guidelines are applied to a variety of frameworks from published studies. Scientific professions, such as nursing, use theories to organize their body of knowledge and establish what is known about a phenomenon. Formally, a theory is defined as a set of concepts and statements that present a view of a phenomenon. Concepts are terms that abstractly describe and name an object, idea, experience, or phenomenon, thus providing it with a separate identity or meaning. Concepts are defined in a particular way to present the ideas relevant to a theory. For example, Dunn (2004, 2005) developed definitions for the concepts of adaptation and chronic pain in her theory. The statements in a theory describe how the concepts are connected to each other. A phenomenon (the plural form is phenomena) is the appearance, objects, and aspects of reality as we experience them (Rodgers, 2005). You may understand the phenomenon of taking an examination in a course or the phenomenon of receiving news of your acceptance into nursing school. As nurses, we intervene in the phenomena of pain, fear, and uncertainty of our patients. The phenomenon termed social support introduced earlier is a concept. A concept is the basic element of a theory. Each concept in a theory needs to be defined by the theorist. The definition of a concept might be detailed and complete, or it might be vague and incomplete and require further development (Chinn & Kramer, 2011). Theories with clearly identified and defined concepts provide a stronger basis for a study framework. Two terms closely related to concept are construct and variable. In more abstract theories, concepts have very general meanings and are sometimes referred to as constructs. A construct is a broader category or idea that may encompass several concepts. For example, a construct for the concept of social support might be resources. Another concept that is a resource might be household income. At a more concrete level, terms are referred to as variables and are narrow in their definition. Thus a variable is more specific than a concept. The word variable implies that the term is defined so that it is measurable and suggests that numerical values of the term are able to vary (are variable) from one instance to another. The levels of abstraction of constructs, concepts, and variables are illustrated with an example in Figure 7-1. A variable related to social support might be emotional support. The researchers might define emotional support as a study subject’s rating of the extent of emotional encouragement or affirmation that he or she receives during a stressful time. The measurement of the variable is a specific method for assigning numerical values to varying amounts of emotional social support. Subjects would respond to questions on a survey or questionnaire about emotional support and their individual answers would be reported as scores. For example, the Functional Social Support Questionnaire has a three-item subscale that measures perceived emotional support (Broadhead, Gehlbach, de Gruy, & Kaplan, 1988; Mas-Expósito, Amador-Campos, Gómez-Benito, & Lalucat-Jo, 2011). One of the items was “People care what happens to me,” and the others addressed whether the respondent felt loved and received praise for doing a good job (Broadhead et al., 1988, p. 722). If the Functional Social Support Questionnaire was used by researchers in a study, the subjects’ answers to the three items would be added together as the total score. The subjects’ total scores on the three questions would be the measurement of the variable of perceived emotional support. (Chapter 10 provides a detailed discussion of measurement methods.) The conceptual definition that a researcher identifies or develops for a concept comes from a theory and provides a basis for the operational definition. Remember that in quantitative studies, each variable is ideally associated with a concept, conceptual definition, and operational definition. The operational definition is how the concept can be manipulated, such as an intervention or independent variable, or measured, such as a dependent or outcome variable (see Chapter 5). Conceptual definitions may be explicit or implicit. It is important that you identify the researcher’s conceptual definitions of study variables when you critically appraise a study. Nichols, Rice, and Howell (2011) conducted a study with 73 overweight children who were 9 to 11 years old to examine the relationships among anger, stress, and blood pressure. Although the researchers did not identify the conceptual definitions in the report of the study, the definitions can be extracted from the study’s framework. The implicit conceptual definition and operational definition for one concept in the study, trait anger, are presented in Table 7-1. Conceptual and operational definitions of variables are described in detail in Chapter 5. Table 7-1 Conceptual and Operational Definitions for Trait Anger in the Study of Overweight Children Adapted from Jacobs, G. & Blumer, C. (1984). The Pediatric Anger Scale. Vermillion, SD: University of South Dakota, Department of Psychology; and from Nichols, Rice, & Howell, 2011. A relational statement clarifies the type of relationship that exists between or among concepts. For example, in the study just mentioned, Nichols and colleagues (2011) proposed that high levels of trait anger were related to high blood pressure in overweight children. They also proposed that high blood pressure was influenced by patterns of anger expression and stress. In regard to the effects of stress on blood pressure, they provided more detail about how stress affected blood pressure by describing the relationships among the corticotropin-releasing factor, stress response, rate and stroke volume of the heart, cardiac output, and constriction of the blood vessels that result in changes in blood pressure. The statements of the physiological processes explaining the connections between stress and blood pressure were also relational statements. Figure 7-2 is the diagram that the researchers provided to display the relationships of their framework. In theories, propositions (relational statements) can be expressed at various levels of abstraction. Theories that are more abstract (grand nursing theories) contain relational statements that are called general propositions (Grove et al., 2013). Stating a relationship in a more narrow way makes the statement more concrete and testable and results in a specific proposition. Specific propositions in less abstract frameworks (middle range theories) may lead to hypotheses. Hypotheses are developed based on propositions from a grand or middle range theory that comprise the study’s framework. Hypotheses, written at a lower level of abstraction, are developed to be tested in a study. Statements at varying levels of abstraction that express relationships between or among the same conceptual ideas can be arranged in hierarchical form, from general to specific. Table 7-2 provides three examples of relationships between two concepts that are written as general propositions, specific propositions, and hypotheses. The first general proposition includes the constructs of enduring personality traits and physiological responses and could be applied to enduring personality traits, such as determination or self-confidence. In this case, the specific proposition indicates that the enduring personality trait is trait anger and the physiological response is blood pressure. The hypothesis proposes a specific relationship between trait anger and blood pressure that was tested in the study (Nichols et al., 2011). Table 7-2 Examples of Logical Links* In a Study of Trait Anger, Patterns of Anger Expression, Stress, and Blood Pressure in Overweight Children *Between relational statements from abstract to concrete. From Nichols, K. H., Rice, M., & Howell, C. (2011). Anger, stress, and blood pressure in overweight children. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 26(5), 446-455. Early nurse scholars labeled the most abstract theories as conceptual models or conceptual frameworks. For example, Roy (Roy & Andrews, 2008) described adaptation as the primary phenomenon of interest to nursing in her model. This model identifies the elements considered essential to adaptation and describes how the elements interact to produce adaptation and thus health. In contrast, Orem (Orem & Taylor, 2011) presents her descriptions of health phenomena in terms of self-care, self-care deficits, and nursing systems. Both these theories have been called conceptual models. What can be confusing is that other scholars do not label Roy’s and Orem’s writings as conceptual models, but classify them as grand nursing theories (Peterson & Bredow, 2009). Because of this lack of agreement, we will use the term grand nursing theories in this book to describe the nursing theories that are more abstract. We will reserve the term model to refer to a diagram that graphically presents the concepts and relationships of a framework being used to guide a study. Table 7-3 lists several well-known grand nursing theories, with a brief explanation. Table 7-3 Selected Grand Nursing Theories Building a body of knowledge related to a particular grand nursing theory requires an organized program of research and a group of scholars. The Roy Adaptation Model (RAM) has been used as the basis for studies for over 25 years. The Roy Adaptation Association is a group of researchers who “analyze, critique, and synthesize all published studies in English based on the RAM” (Roy, 2011, p. 312). The Society of Rogerian Scholars continues to conduct studies and develop knowledge related to Martha Rogers’ Science of Unitary Human Beings (http://www.societyofrogerianscholars.org/index.html). The International Orem Society publishes a journal, Self-Care, Dependent-Care, & Nursing, to disseminate research and clinical applications of Dorothea Orem’s theory of self-care. These are examples of researchers who maintain a network to communicate with each other and other nurses about their work with a specific theoretical approach. Middle range theories are less abstract and narrower in scope than grand nursing theories. These types of theories specify factors such as a patient’s health condition, family situation, and nursing actions and focus on answering particular practice questions (Alligood & Tomey, 2010). Middle range theories are more closely linked to clinical practice and research than grand nursing theories and therefore have a greater appeal to nurse clinicians and researchers. They may emerge from a grounded theory study, be deduced from a grand nursing theory, or created through a synthesis of theories on a particular topic. Middle range theories also can be used as the framework for a study, thus contributing to the validation of the middle range theory (Peterson & Bredow, 2009). Table 7-4 lists some of the middle range theories currently being used as frameworks in nursing studies. These published middle range theories have clearly identified concepts, definitions of concepts, and relational statements and are referred to as substantive theories. These theories are labeled as substantive because they are closer to the substance of clinical practice. For example, clinical practice involves nursing actions to help the patient be comfortable. Kolcaba and Kolcaba (1991) analyzed the concept of comfort. They defined comfort as the state of relief, ease, and transcendence that is experienced in the physical, psychospiritual, environmental, and social contexts of a person. From that concept analysis, a middle range theory of comfort was developed that is applicable to practice and research. “According to the theory, enhanced comfort strengthens recipients….to engage in activities necessary to achieving health and remaining healthy” (Kolcaba & DiMarco, 2005, p.189). Table 7-4

Understanding Theory and Research Frameworks

What is a Theory?

Understanding the Elements of Theory

Concepts

Concept

Variable

Conceptual Definition

Operational Definition

Anger

Trait anger

Enduring personality characteristic reflected in the fury, rage, and displeasure experienced over time (Nichols, Rice, & Howell, 2011)

Trait anger subscale of the Jacobs Pediatric Trait Anger Scale (PPS-2; Jacobs & Blumer, 1984; Nichols et al., 2011, p. 449)

Relational Statements

General Proposition

Specific Proposition

Hypothesis

Enduring personality traits are associated with physiological responses to the environment.

Trait anger is associated with blood pressure.

Among overweight children, high levels of trait anger are associated with high systolic and diastolic blood pressures.

Patterns of emotional responses are associated with physiological responses to the environment.

Patterns of anger expression are associated with blood pressure.

Among overweight children, anger expressed outwardly is associated with high systolic and diastolic blood pressures.

Emotional stress is associated with physiological responses to the environment.

Stressful events are associated with blood pressure.

Among overweight children, high levels of perceived daily stress are associated with high systolic and diastolic blood pressures.

Levels of Theoretical Thinking

Grand Nursing Theories

Name

Author (Year)

Brief Description

Adaptation Model

Roy & Andrews (2008)

In response to focal, contextual, and residual stimuli, people adapt by using a variety of processes and systems, some of which are automatic and some of which are learned. The overall goal is to return to homeostasis and promote growth.

Self-Care Deficit Theory of Nursing

Orem (2001)

Individuals’ ability to care for themselves is affected by developmental stage, presence of disease, and available resources and may result in a self-care deficit. The goal of nursing is to provide care in proportion to the person’s self-care capacity.

Systems Model

Neuman & Fawcett (2002)

Stressors can pose a threat to the core processes of the individual. The core is protected by concentric circles of resistance and defense.

Theory of Caring

Watson (1985)

Human caring is a central process of life that influences health. A nurse may create caring moments with a patient by being an authentic human and acknowledging the uniqueness of the patient.

Middle Range and Practice Theories

Theory

Relevant Theoretical Sources

Acute pain

Good, 1998; Good & Moore, 1996

Acute pain management

Huth & Moore, 1998

Adaptation to chronic pain

Dunn, 2004, 2005

Adapting to diabetes mellitus

Whittemore & Roy, 2002

Adolescent vulnerability to risk behaviors

Cazzell, 2008

Caregiver stress

Tsai, 2003

Caring

Swanson, 1991

Chronic pain

Tsai, Tak, Moore, & Palencia, 2003

Chronic sorrow

Eakes, Burke, & Hainsworth, 1998

Client Expression Model

Holland, Gray, & Pierce, 2011

Crisis emergencies for individuals with severe, persistent mental illnesses

Brennaman (2012)

Comfort

Kolcaba, 1994

Culturing brokering

Jezewski, 1995

Health promotion

Pender, Murdaugh, & Parsons, 2006

Home care

Smith, Pace, Kochinda, Kleinbeck, Koehler, & Popkess-Vawter, 2002

Nursing intellectual capital

Covell, 2008

Peaceful end of life

Ruland & Moore, 1998

Postpartum weight management

Ryan, Weiss, Traxel, & Brondino, 2011

Resilience

Polk, 1997

Self-care management for vulnerable populations

Dorsey & Murdaugh, 2003

Uncertainty in illness

Mishel, 1988, 1990

Unpleasant symptoms

Lenz, Pugh, Milligan, Gift, & Suppe, 1997

Urine control theory

Jirovec, Jenkins, Isenberg, & Baiardi, 1999 ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Understanding Theory and Research Frameworks

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access