Chapter 8 Understanding effectiveness for service planning

Introduction

Surely effective public health care is good health care? It does what is intended to do, which is to restore or promote health or to prevent illness. The difficulty arrives when it comes to deciding the appropriate outcomes, the appropriate ways of defining them and the appropriate way of determining whether the desired outcome has been achieved. This is the problem of determining effectiveness. It is often at its most problematic when dealing with complex, multi-faceted interventions, which have multiple outcomes and operate through complex mechanisms. Many public health interventions undertaken by public health practitioners are of this type. Public health practitioners are increasingly expected to contribute to service planning too, perhaps as members of a Primary Care Trust (PCT), or in a working group for one or more aspects of a Local Strategic Partnership (LSP) or Local Delivery Plan (LDP) (see Chapters 3 and chapter 7). How can they choose which services will best meet the health needs? Those seeking evidence to use in planning public health services need to consider the type of evidence needed and the value of that evidence very carefully, prior to putting any intervention into effect.

Much of the debate about effectiveness is fuelled by competing approaches to scientific enquiry and arguments about the nature of human knowledge and experience. Those who are tempted to paddle in these turbulent philosophical waters are advised to bear in mind that at the heart of the effectiveness debate lies a simple purpose. To put it most plainly, we wish to determine whether our actions had an effect and whether that effect was that which we intended. For public health interventions, the desired effect is ‘health’, construed in its broadest sense to encompass a range of human experiences from the relief of physical illness through to positive aspects of wellbeing in individuals or groups.

Defining effectiveness

Muir Gray (2001) offers a simple definition of effectiveness. The effectiveness of a health care service or professional is the extent to which desired outcomes are achieved in practice (p. 185). Effectiveness is distinguished from quality, which is seen as the adherence to (best) standards of care delivery. Although you might generally expect that standards of care be set in order to deliver the most effective care possible, this is frequently not the case. One reason for this is that the effectiveness of many health care interventions is simply not known. In many cases (perhaps all) the goal is not necessarily the most effective care possible for a specific problem, but that which yields the best effect within parameters that are dictated by financial resources and decisions about allocating resources across a range of interventions for a variety of problems. Further, since the effects of health care interventions are generally multi-faceted, the most effective approach to care depends upon the value ascribed to different outcomes, which varies across individuals and groups. Effectiveness must also be distinguished from efficacy, the impact of an intervention in ideal circumstances, as opposed to everyday practice.

Should the distinction between quality and effectiveness seem unconvincing, it may help to consider an alternative framework for defining quality in health care. According to Donabedian, a health outcome is, ‘… the effect of care on the health and welfare of individuals or populations’ (Donabedian 1988, p. 177). Donabedian’s work distinguishes outcome from process (‘… care itself’) and structure (‘… the characteristics of the settings in which care is delivered’) (1988, p. 177). Although the validity of any quality indicator is predicated upon a re-lationship between that indicator and some dimension of patient health or wellbeing, it is frequently the case that this relationship is hypothetical (Donabedian 1966). Quality in the structures and processes of care is not necessarily based on a proven link to outcomes, i.e. effectiveness (see Chapter 13 for more information about quality).

A hypothetical example might illustrate these differences. Suppose that we designed a fall-prevention programme for elderly people. We choose to implement it through individualised visits to people identified as at-risk by a specially trained public health practitioner. The programme consisted of an assessment of risk in the home, advice on exercise and feedback to the GP about any risks to the individual from their medication regime and the need for any further medical assessment.

A research study demonstrates that the programme dramatically reduces the number of falls experienced by the target group when compared to an appropriate comparison group who do not receive it, and it is deemed a success. Such a research study would almost certainly have at its core a randomised controlled trial in which clients are randomly allocated to receive the fall-prevention programme or a control intervention, which would probably be simply GP follow-up. At this point the programme has been identified as having efficacy, since it has worked, albeit in these special circumstances. A range of such studies have, in fact, been done, which provide some evidence for a health/environmental risk factor screening assessment and individually tailored interventions in preventing falls (Gillespie et al 2003), although research has not generally examined the specific contribution of public health practitioners.

Evidence-based health care

Evidence-based medicine has been defined as ‘… the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients’ (Sackett et al 1996, p. 71). The approach is not, however, restricted to decisions about medical care nor to the care of individual patients. EBHC is more broadly defined in terms of decision making about the health care of individual patients, groups of patients and populations (Muir Gray 2001) and it is this broader term that is used here. Although the particular set of practices and principles that represent the current EBHC movement emerged into the mainstream of practice only during the mid 1990s, its advocates claim illustrious ancestors.

Origins in public health practice

The link between public health practice and EBHC is firmly established. Authors in the area often seek to establish its lineage by tracing its roots to the pioneering studies including the epidemiological work of Semmelweiss and Oliver Wendel Holmes, both of whom identified the role of health care practitioners in causing puerperal fever through lack of basic hygiene (Rangachari 1997). Systematic observation allowed Holmes to discern that incidence of puerperal fever seemed to be in clusters that were associated with particular physicians and concluded that these physicians were transmitting the disease-causing agent from one woman to another. Semmelweiss’ comparison of infection rates in women cared for by doctors (who did not wash their hands when attending to women after post-mortem examinations) and midwives (who were not contaminated in this way) is held up as an early prototype for today’s randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

If Holmes and Semmelweiss are claimed as its grandfathers, Archie Cochrane, an epidemiologist who worked on the earliest RCTs conducted by the Medical Research Council in the UK, could be said to be the father of today’s EBHC movement. After a lifetime spent working on studies of effectiveness he complained, ‘It is surely a great criticism of our profession that we have not organised a critical summary, by specialty or subspecialty, adapted periodically, of all relevant randomised controlled trials’ (Chalmers 1997). For Cochrane, an unbiased synthesis of evidence from good-quality studies is the true endpoint of health research. He campaigned for effective health care to be free in the National Health Service (NHS), but equally argued that interventions with no evidence of effectiveness should not be offered unless as part of a well-designed research programme.

Use of evidence

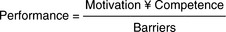

Muir Gray (2001) reduces the problem of identification and utilisation of evidence of effectiveness to a simple algebraic formulation (which I suspect he would not wish us to take too literally). In his formulation the decision-maker’s performance as an ‘evidence-based decision-maker’ is proportional to motivation (to utilise evidence) and competence (in identifying, appraising and interpreting evidence). It is inversely related to barriers which, in Muir Gray’s account, are lack of resources for accessing evidence (Figure 8.1).

Muir Gray’s term ‘motivation’ covers a complex set of cognitive processes, which are often touched on in studies of research utilisation. In the extreme case it has been frequently argued that practitioners will simply disbelieve or dis-regard evidence if it does not accord with pre-existing beliefs (Hunt 1996, Jones 1997, Rodgers 1994). Within the paradigm of EBHC, these complex factors are essentially irrational, in that they will tend to lead the individual toward making an incorrect decision (or to be sufficiently unmotivated as to make no decision at all).

The experiences of the early pioneers Semmelweiss and Wendel Holmes illustrate that the power of rational argument alone is not enough to ensure that evidence is implemented. Semmelweiss was eventually dismissed from his job in Vienna and forced to return to his native Hungary, after failing to find further work. Wendel Homes was the subject of considerable scorn from eminent practitioners for many years, before his findings were finally accepted. One detects a whiff of anti-semitism in the treatment of Semelweiss and it is clear that the perceptions of the messenger have considerable impact upon people’s willingness to listen to the message. This is a complex topic, and one that is well outside the remit of this chapter, although readers might like to consult two excellent reviews of implementing evidence that have been commissioned by the NHS in recent years (Greenhalgh et al 2004, NHS CRD 1999).

There is, however, one issue of substantive import that must be addressed prior to moving on. I would not wish to ally myself to an extreme relativist pos-ition on knowledge. Absolute relativism has little place in a practice discipline where all parties must accept (if only on pragmatic grounds) that individuals do not completely construct their own realities. Events such as survival and death are of fundamental significance and subject to external verification. However, this does not necessarily mean that the evidence available for rational scrutiny is not subject to interpretation. What one party may perceive as useful evidence may not necessarily be seen as such by another. The questions asked about health care practice are selective and the answers that are published are also filtered and selected according to particular world views. It is not that practitioners are free to construct any version of reality that they choose, but equally the available evidence cannot be said to simply purvey objective ‘truth’ in any absolute sense either (Griffiths 2005).

First, the literature on evidence-based practice clearly describes the basis on which many health care policy and practice decisions can be, and are, made. Indeed, although by no means ubiquitous (see Sheldon et al 1996), the EBHC model is probably now the dominant one in current health services research and research policy. Certainly, the majority of initiatives that resulted from the UK’s NHS research and development and information strategies in the early 1990s (e.g. the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination; the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, which now incorporates the former Health Development Agency; the Health Technology Assessment programme; Health Scotland, which combines the former Health Education Board for Scotland and Public Health Institute for Scotland and the National Library for Health; see Box 8.1) seem to adhere broadly to the tenets of the model. The second reason is that the model’s critique of many aspects of current (‘evidence less’) practice is compelling, as are some of the solutions offered. The following sections will describe the nature of the evidence that the evidence-based decision-maker is urged to use in order to ensure patients and clients receive the most effective health care.

Hierarchy of evidence

The problem of using non-random groups to compare the effectiveness of interventions is clear when considering a hypothetical comparison of two head-lice treatments. Imagine treatment X is the most expensive pediculocide on the market. If we simply compared those children whose parent bought and used treatment X with those who received the extremely cheap treatment Y it is difficult to determine what caused any observed differences in louse infestation. Treatment X may appear more effective because it is more diligently applied by parents who have invested heavily in treatments. Alternatively, treatment Y might appear more effective because it tended to be bought by parents who thought they ought to treat ‘just in case’, but had in fact seen no lice. The permutations are endless, but just about any pattern of outcomes could be accounted for by explanations other than differential effectiveness in treatments.

Complex techniques of design and analysis are deployed to improve the validity of results from such non-randomised (quasi-) experiments (Cook & Campbell 1979). All are essentially designed to control for the effect of extraneous causes that might lead to differences between groups, and thus to increase the confidence with which cause can be attributed to the intervention under investigation. In essence, the endeavour is to make the quasi-experiment as much like the RCT as possible. Thus, alternative study designs represent no shift in the paradigm. Rather they represent best fixes for technical problems that mitigate against the use of an RCT.

Nonetheless, two of the leading authors in the field offer the following observations: ‘With the data usually available for such studies, there is simply no logical or statistical procedure that can be counted on to make proper allowances for uncontrolled pre-existing differences between groups’ (Lord 1967, p. 305 cited in Cook & Campbell 1979). In other words, nothing really beats a good RCT, a point emphasised by Muir Gray (2001): ‘The main abuse of a cohort study is to assess the effectiveness of a particular intervention when a more appropriate method would be an RCT’ (p. 150).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree