Discuss some controversies relating to the issue of quality in qualitative research

Identify the quality criteria proposed in a major framework for evaluating quality and integrity in qualitative research

Identify the quality criteria proposed in a major framework for evaluating quality and integrity in qualitative research

Discuss strategies for enhancing quality in qualitative research

Discuss strategies for enhancing quality in qualitative research

Describe different dimensions relating to the interpretation of qualitative results

Describe different dimensions relating to the interpretation of qualitative results

Define new terms in the chapter

Define new terms in the chapter

Key Terms

Audit trail

Audit trail

Authenticity

Authenticity

Confirmability

Confirmability

Credibility

Credibility

Data triangulation

Data triangulation

Dependability

Dependability

Disconfirming cases

Disconfirming cases

Inquiry audit

Inquiry audit

Investigator triangulation

Investigator triangulation

Member check

Member check

Method triangulation

Method triangulation

Negative case analysis

Negative case analysis

Peer debriefing

Peer debriefing

Persistent observation

Persistent observation

Prolonged engagement

Prolonged engagement

Reflexivity

Reflexivity

Researcher credibility

Researcher credibility

Thick description

Thick description

Transferability

Transferability

Triangulation

Triangulation

Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness

Integrity in qualitative research is a critical issue for both those doing the research and those considering the use of qualitative evidence.

PERSPECTIVES ON QUALITY IN QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

Qualitative researchers agree on the importance of doing high-quality research, yet defining “high quality” has been controversial. We offer a brief overview of the arguments of the debate.

Debates About Rigor and Validity

One contentious issue concerns use of the terms rigor and validity—terms some people shun because they are associated with the positivist paradigm. For these critics, the concept of rigor is by its nature a term that does not fit into an interpretive paradigm that values insight and creativity.

Others disagree with those opposing the term validity. Morse (2015), for example, has argued that qualitative researchers should return to the terminology of the social sciences—i.e., rigor, reliability, validity, and generalizability.

The complex debate has given rise to a variety of positions. At one extreme are those who think that validity is an appropriate quality criterion in both quantitative and qualitative studies, although qualitative researchers use different methods to achieve it. At the opposite extreme are those who berate the “absurdity” of validity. A widely adopted stance is what has been called a parallel perspective. This position was proposed by Lincoln and Guba (1985), who created standards for the trustworthiness of qualitative research that parallel the standards of reliability and validity in quantitative research.

Generic Versus Specific Standards

Another controversy concerns whether there should be a generic set of quality standards or whether specific standards are needed for different qualitative traditions. Some writers believe that research conducted within different disciplinary traditions must attend to different concerns and that techniques for enhancing research integrity vary. Thus, different writers have offered standards for specific forms of qualitative inquiry, such as grounded theory, phenomenology, ethnography, and critical research. Some writers believe, however, that some quality criteria are fairly universal within the constructivist paradigm. For example, Whittemore and colleagues (2001) prepared a synthesis of criteria that they viewed as essential to all qualitative inquiry.

Terminology Proliferation and Confusion

The result of these controversies is that there is no common vocabulary for quality criteria in qualitative research. Terms such as truth value, goodness, integrity, and trustworthiness abound, but each proposed term has been refuted by some critics. With regard to actual criteria for evaluating quality in qualitative research, dozens have been suggested. Establishing a consensus on what the quality criteria should be, and what they should be named, remains elusive.

Given the lack of consensus and the heated arguments supporting and contesting various frameworks, it is difficult to provide guidance about quality standards. We present information about criteria from the Lincoln and Guba (1985) framework in the next section. (Criteria from another framework are described in the supplement to this chapter on  website.) We then describe strategies that researchers use to strengthen integrity in qualitative research. These strategies should provide guidance for considering whether a qualitative study is sufficiently rigorous, trustworthy, insightful, or valid.

website.) We then describe strategies that researchers use to strengthen integrity in qualitative research. These strategies should provide guidance for considering whether a qualitative study is sufficiently rigorous, trustworthy, insightful, or valid.

LINCOLN AND GUBA’S FRAMEWORK OF QUALITY CRITERIA

Although not without critics, the criteria often viewed as the “gold standard” for qualitative research are those outlined by Lincoln and Guba (1985). These researchers suggested four criteria for developing the trustworthiness of a qualitative inquiry: credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability. These criteria represent parallels to the positivists’ criteria of internal validity, reliability, objectivity, and external validity, respectively. In later writings, responding to criticisms and to their own evolving views, a fifth criterion more distinctively aligned with the constructivist paradigm was added: authenticity (Guba & Lincoln, 1994).

Credibility

Credibility refers to confidence in the truth value of the data and interpretations of them. Qualitative researchers must strive to establish confidence in the truth of the findings for the particular participants and contexts in the research. Lincoln and Guba (1985) pointed out that credibility involves two aspects: first, carrying out the study in a way that enhances the believability of the findings, and second, taking steps to demonstrate credibility to external readers. Credibility is a crucial criterion in qualitative research that has been proposed in several quality frameworks.

Dependability

Dependability refers to the stability (reliability) of data over time and over conditions. The dependability question is Would the study findings be repeated if the inquiry were replicated with the same (or similar) participants in the same (or similar) context? Credibility cannot be attained in the absence of dependability, just as validity in quantitative research cannot be achieved in the absence of reliability.

Confirmability

Confirmability refers to objectivity—the potential for congruence between two or more independent people about the data’s accuracy, relevance, or meaning. This criterion is concerned with establishing that the data represent the information participants provided and that the interpretations of those data are not imagined by the inquirer. For this criterion to be achieved, the findings must reflect the participants’ voice and the conditions of the inquiry and not the researcher’s biases.

Transferability

Transferability, analogous to generalizability, is the extent to which qualitative findings have applicability in other settings or groups. Lincoln and Guba (1985) noted that the investigator’s responsibility is to provide sufficient descriptive data that readers can evaluate the applicability of the data to other contexts: “Thus the naturalist cannot specify the external validity of an inquiry; he or she can provide only the thick description necessary to enable someone interested in making a transfer to reach a conclusion about whether transfer can be contemplated as a possibility” (p. 316).

Authenticity

Authenticity refers to the extent to which researchers fairly and faithfully show a range of different realities. Authenticity emerges in a report when it conveys the feeling tone of participants’ lives as they are lived. A text has authenticity if it invites readers into a vicarious experience of the lives being described and enables readers to develop a heightened sensitivity to the issues being depicted. When a text achieves authenticity, readers are better able to understand the lives being portrayed “in the round,” with some sense of the mood, experience, language, and context of those lives.

STRATEGIES TO ENHANCE QUALITY IN QUALITATIVE INQUIRY

This section describes some of the strategies that qualitative researchers can use to establish trustworthiness in their studies. We hope this description will prompt you to carefully assess the steps researchers did or not take to enhance quality.

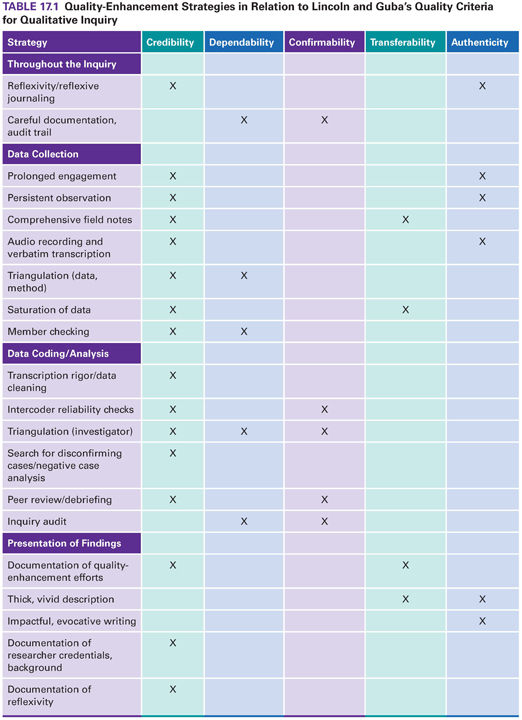

We have not organized strategies according to the five criteria just described (e.g., strategies researchers use to enhance credibility) because many strategies simultaneously address multiple criteria. Instead, we have organized strategies by phase of the study—data collection, coding and analysis, and report preparation. Table 17.1 indicates how various quality-enhancement strategies map onto Lincoln and Guba’s (1985) criteria.

Quality-Enhancement Strategies During Data Collection

Some of the strategies that qualitative researchers use are difficult to discern in a report. For example, intensive listening during an interview, careful probing to obtain rich and comprehensive data, and taking pains to gain participants’ trust are all strategies to enhance data quality that cannot easily be communicated in a report. In this section, we focus on some strategies that can be described to readers to increase their confidence in the integrity of the study results.

Prolonged Engagement and Persistent Observation

An important step in establishing integrity in qualitative studies is prolonged engagement—the investment of sufficient time collecting data to have an in-depth understanding of the culture, language, or views of the people or group under study; to test for misinformation; and to ensure saturation of important categories. Prolonged engagement is also important for building trust with informants, which in turn makes it more likely that useful and rich information will be obtained.

Example of prolonged engagement

Zakerihamidi and colleagues (2015) conducted a focused ethnographic study of pregnant women’s perceptions of vaginal versus cesarean section in Iran. The lead researcher had “long-term involvement with the participants during data collection” (p. 43). It was noted that “the researcher fully immersed herself in the culture related to the selection of the mode of delivery” (p. 42).

High-quality data collection in qualitative studies also involves persistent observation, which concerns the salience of the data being gathered. Persistent observation refers to the researchers’ focus on the characteristics or aspects of a situation that are relevant to the phenomena being studied. As Lincoln and Guba (1985) noted, “If prolonged engagement provides scope, persistent observation provides depth” (p. 304).

Example of persistent observation

Nortvedt and colleagues (2016) conducted a qualitative study of 14 immigrant women on long-term sick leave during their rehabilitation in Norway. In addition to interviews, the first author conducted participant observation during two rehabilitation courses at an outpatient clinic. Each course occurred over 10 days for 10 weeks each. The total number of hours of observation of these immigrant women was 45 hours.

Reflexivity Strategies

Reflexivity involves awareness that the researcher as an individual brings to the inquiry a unique background, set of values, and a professional identity that can affect the research process. Reflexivity involves attending continually to the researcher’s effect on the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data.

The most widely used strategy for maintaining reflexivity is to maintain a reflexive journal or diary. Reflexive writing can be used to record, in an ongoing fashion, thoughts about how previous experiences and readings about the phenomenon are affecting the inquiry. Through self-interrogation and reflection, researchers seek to be well positioned to probe deeply and to grasp the experience, process, or culture under study through the lens of participants.

| TIP Researchers sometimes begin a study by being interviewed themselves with regard to the phenomenon under study. Of course, this approach is possible only if the researcher has experienced that phenomenon. |

Triangulation refers to the use of multiple referents to draw conclusions about what constitutes truth. The aim of triangulation is to “overcome the intrinsic bias that comes from single-method, single-observer, and single-theory studies” (Denzin, 1989, p. 313). Triangulation can also help to capture a more complete, contextualized picture of the phenomenon under study. Denzin (1989) identified four types of triangulation (data triangulation, investigator triangulation, method triangulation, and theory triangulation), and other types have been proposed. Two types are relevant to data collection.

Data triangulation involves the use of multiple data sources for the purpose of validating conclusions. There are three types of data triangulation: time, space, and person. Time triangulation involves collecting data on the same phenomenon or about the same people at different points in time (e.g., at different times of the year). This concept is similar to test–retest reliability assessment—the point is not to study a phenomenon longitudinally to assess change but to establish the congruence of the phenomenon across time. Space triangulation involves collecting data on the same phenomenon in multiple sites to test for cross-site consistency. Finally, person triangulation involves collecting data from different types or levels of people (e.g., patients, health care staff) with the aim of validating data through multiple perspectives on the phenomenon.

Example of person and space triangulation

Mill and a multidisciplinary team (2013) undertook participatory action research in four countries (Jamaica, Kenya, Uganda, and South Africa) to explore stigma in AIDS nursing care. They gathered data from frontline registered nurses, enrolled nurses, and midwives, using personal and focus group interviews. They noted that triangulation was specifically designed to “enhance the rigor of the study” (p. 1068).

Method triangulation involves using multiple methods of data collection. In qualitative studies, researchers often use a rich blend of unstructured data collection methods (e.g., interviews, observations, documents) to develop a comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon. Diverse data collection methods provide an opportunity to evaluate the extent to which a consistent and coherent picture of the phenomenon emerges.

Example of method triangulation

Nilmanat and coresearchers (2015) studied the end-of-life experiences of Thai patients with advanced cancer. Patients were interviewed multiple times, and interviews lasted about an hour each. In-depth observations were made in the participants’ homes, in hospitals, and at their funeral ceremonies at Buddhist temples.

Comprehensive and Vivid Recording of Information

In addition to taking steps to record interview data accurately (e.g., via careful transcriptions of recorded interviews), researchers ideally prepare field notes that are rich with descriptions of what transpired in the field—even if interviews are the primary source of data.

Some researchers specifically develop an audit trail—a systematic collection of materials that would allow an independent auditor to draw conclusions about the data. An audit trail might include the raw data (e.g., interview transcripts), methodologic and reflexive notes, topic guides, and data reconstruction products (e.g., drafts of the final report). Similarly, the maintenance of a decision trail that articulates the researcher’s decision rules for categorizing data and making analytic inferences is a useful way to enhance the dependability of the study. When researchers share some decision trail information in their reports, readers can better evaluate the soundness of the decisions.

Example of an audit trail

In their phenomenological study of the illness experiences of patients suffering with rare diseases and of the health care providers who care for them, Garrino and colleagues (2015) maintained careful documentation and an audit trail to enhance credibility.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree