Trends and Issues

Objectives

1. Describe the subjective and objective ways that aging is defined.

2. Identify personal and societal attitudes toward aging.

4. Discuss the myths that exist with regard to aging.

5. Identify recent demographic trends and their impact on society.

6. Describe the effects of recent legislation on the economic status of older adults.

7. Identify the political interest groups that work as advocates for older adults.

8. Identify the major economic concerns of older adults.

9. Describe the housing options that are available to older adults.

10. Discuss the health care implications of an increase in the population of older adults.

11. Describe the changes in family dynamics that occur as family members become older.

12. Examine the role of nurses in dealing with an aging family.

13. Identify the different forms of elder abuse.

14. Recognize the most common signs of abuse.

15. Describe approaches that are effective in preventing elder abuse.

Key Terms

abuse (p. 22)

chronologic age (krŏ-nŏ-LŎJ- k) (p. 2)

k) (p. 2)

cohort (KŌ-hŏrt) (p. 8)

demographics (dĕm-ŏ-GRĂF- ks) (p. 6)

ks) (p. 6)

geriatric (jĕr-ē-ĂT-r k) (p. 2)

k) (p. 2)

neglect (n -glĕkt) (p. 22)

-glĕkt) (p. 22)

respite (RĔS-p t) (p. 26)

t) (p. 26)

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Wold/geriatric

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Wold/geriatric

Introduction to geriatric nursing

Historical Perspective on the Study of Aging

Until the middle of the nineteenth century, only two stages of human growth and development were identified: childhood and adulthood. In many ways, children were treated like small adults. No special attention was given to them or to their needs. Families had to produce many children to ensure that a few would survive and reach adulthood. In turn, children were expected to contribute to the family’s survival. Little or no concern was given to those characteristics and behaviors that set one child apart from another.

As time passed, society began to view children differently. People learned that there were significant differences between children of different ages and that children’s needs changed as they developed. Childhood is now divided into substages (e.g., infant, toddler, preschool, school age, and adolescence). Each stage is associated with unique challenges related to the individual child’s stage of growth and development. Because the substages are related to obvious physical changes or to significant life events, this classification method is now accepted as logical and necessary.

Until recently, society also viewed adults of all ages interchangeably. Once you became an adult, you remained an adult. Perhaps society perceived dimly that older adults were different from younger adults, but it was not greatly concerned with these differences because few people lived to old age. In addition, the physical and developmental changes during adulthood are more subtle than those during childhood; therefore, these changes received little attention.

Until the 1960s, sociologists, psychologists, and health care providers focused their attention on meeting the needs of the typical or average adult: people between 20 and 65 years of age. This group was the largest and most economically productive segment of the population; they were raising families, working, and contributing to the growth of the economy. Only a small percentage of the population lived beyond 65 years of age. Disability, illness, and early death were accepted as natural and unavoidable.

In the late 1960s, research began to indicate that adults of all ages are not the same. At the same time, the focus of health care shifted from illness to wellness. Disability and disease were no longer considered unavoidable parts of aging. Increased medical knowledge, improved preventive health practices, and technologic advances helped more people live longer, healthier lives.

Older adults now constitute a significant group in society, and interest in the study of aging is increasing. The study of aging is expected to be a major area of attention for years to come.

What’s in a Name: Geriatrics, Gerontology, and Gerontics

The term geriatric comes from the Greek words “geras,” meaning old age, and “iatro,” meaning relating to medical treatment. Thus, geriatrics is the medical specialty that deals with the physiology of aging and with the diagnosis and treatment of diseases affecting the aged. Geriatrics, by definition, focuses on abnormal conditions and the medical treatment of these conditions.

The term gerontology comes from the Greek words “gero,” meaning related to old age, and “ology,” meaning the study of. Thus, gerontology is the study of all aspects of the aging process, including the clinical, psychologic, economic, and sociologic problems of older adults and the consequences of these problems for older adults and society. Gerontology affects nursing, health care, and all areas of our society—including housing, education, business, and politics.

The term gerontics, or gerontic nursing, was coined by Gunter and Estes in 1979 to define the nursing care and the service provided to older adults. The aim of gerontic nursing is “to safeguard and increase health to the extent possible and to provide comfort and care to the extent necessary.” This textbook focuses on gerontic nursing. It addresses ways to promote high-level functioning and methods of providing care and comfort for older adults.

The objectives of this book are as follows:

• Examine some of the trends and issues that affect the older person’s ability to remain healthy.

• Explore the theories and myths of aging.

• Study the normal changes that occur with aging.

• Review the pathologic conditions that are commonly observed in older adults.

• Emphasize the importance of effective communication in working with older adults.

• Explore the general methods used to assess the health status of older adults.

• Describe the specific methods of assessing functional needs.

• Explore the impact of medication and medication administration on older adults.

The dictionary defines old as “having lived or existed for a long time.” The meaning of old is highly subjective; to a great degree, it depends on how old we ourselves are. Few people like to consider themselves old. Old age seems to come later as we become older. A recent study reveals that people younger than 30 years view those older than 63 as “getting older.” People 65 years of age and older do not think people are “getting older” until they are 75.

Aging is a complex process that can be described chronologically, physiologically, and functionally. Chronologic age, the number of years a person has lived, is most often used when we speak of aging because it is the easiest to identify and measure. Unfortunately, chronologic age is probably the least meaningful measurement of aging. Many people who have lived a long time remain functionally and physiologically young. These individuals remain physically fit, stay mentally active, and are productive members of society. Others are chronologically young but physically or functionally old.

When we use chronologic age as our measure, authorities use various systems to categorize the aging population (see Table 1-1). To many people, 65 is a magic number in terms of aging. The wide acceptance of age 65 as a landmark of aging is interesting. Since the 1930s, the age of 65 has come to be accepted as the age of retirement, when it is expected that a person willingly or unwillingly stops paid employment. However, before the 1930s, most people worked until they decided to stop working, until they became too ill to work, or until they died. When the New Deal politicians established the Social Security program, they set 65 as the age at which benefits could be collected, but the average life expectancy of the time was 63. The Social Security program was designed as a fairly low-cost way to win votes because most people would not live long enough to collect the benefits. If 65 was considered old then, it certainly is not now. If the same standards were applied today, the retirement age would be 77. However, for various reasons, society clings to 65 as the “retirement age” and resists political proposals designed to move the start of Social Security benefits to a later age. Despite the resistance, the age to qualify for full Social Security benefits is changing. Individuals born before 1937 still qualify for full benefits at age 65, but there are incremental increases in age for all persons born after that time. Individuals born in 1960 or later must wait until age 67 to qualify for full benefits. Reduced benefits are calculated for individuals who claim Social Security benefits after age 62 but before the full retirement age.

Table 1-1

Categorizing the Aging Population

| Age (Years) | Category |

| 55 to 64 | Older |

| 65 to 74 | Elderly |

| 75 to 84 | Aged |

| 85 and older | Extremely aged |

| or | |

| 60 to 74 | Young-old |

| 75 to 84 | Middle-old |

| 85 and older | Old-old |

Attitudes toward aging

Before we look at the attitudes of others, it is important to examine our own attitudes, values, and knowledge about aging. The three Critical Thinking boxes that follow are designed to help you assess how you feel about aging.

Our attitudes are the product of our knowledge and values. Our life experiences and our current age strongly influence our views about aging and old people. Most of us have a rather narrow perspective, and our attitudes may reflect this. We tend to project our personal experiences onto the rest of the world. Because many of us have a somewhat limited exposure to aging, we are likely to believe quite a bit of inaccurate information. When dealing with older adults, our limited understanding and vision can lead to serious errors and mistaken conclusions. If we view old age as a time of physical decay, mental confusion, and social boredom, we are likely to have negative feelings toward aging. Conversely, if we see old age as a time for sustained physical vigor, renewed mental challenges, and social usefulness, our perspective on aging will be quite different.

It is important to separate fact from myth when examining our attitudes about aging. The single most important factor that influences how poorly or how well a person will age is attitude. This statement is true not only for others but also for ourselves.

Throughout time, youth and beauty have been desired (or at least viewed as desirable), and old age and physical infirmity have been loathed and feared. Greek statues portray youths of physical perfection. Artists’ works throughout history have shown heroes and heroines as young and beautiful, and evildoers as old and ugly. Little has changed to this day. Few cultures cherish their older members and view them as the keepers of wisdom. Even in Asia, where tradition demands respect for older adults, societal changes are destroying this venerable mindset.

For the most part, mainstream American society does not value its elders. The United States tends to be a youth-oriented society in which people are judged by age, appearance, and wealth. Young, attractive, and wealthy people are viewed positively; old, imperfect, and poor people are not. It is difficult for young people to imagine that they will ever be old. Despite some cultural changes, becoming old retains many negative connotations. Many people continue to do everything they can to fool the clock. Wrinkles, gray hair, and other physical changes related to aging are actively confronted with makeup, hair dye, and cosmetic surgery. Until recently, advertising seldom portrayed people older than 50 years except to sell eyeglasses, hearing aids, hair dye, laxatives, and other rather unappealing products. The message seemed to be, “Young is good, old is bad; therefore, everyone should fight getting old.” It is significant that trends in advertising appear to be changing. As the number of healthier, dynamic senior citizens with significant spending power has increased, advertising campaigns have become increasingly likely to portray older adults as the consumers of their products, including exercise equipment, health beverages, and cruises. Despite these societal improvements, many people do not know enough about the realities of aging, and, because of ignorance, they are afraid to get old. Interestingly, some studies of the media have found that people who watch more television are likely to have more negative perceptions about aging.

Gerontophobia

The fear of aging and the refusal to accept older adults into the mainstream of society is known as gerontophobia. Senior citizens and younger persons can fall prey to such irrational fears (Box 1-1). Gerontophobia sometimes results in very strange behavior. Teenagers buy antiwrinkle creams. Thirty-year-old women consider facelifts. Forty-year-old women have hair transplants. Long-term marriages dissolve so that one spouse can pursue someone younger. Too often these behaviors may arise from the fear of growing older.

Ageism

The extreme forms of gerontophobia are ageism and age discrimination. Ageism is the disliking of aging and older people based on the belief that aging makes people unattractive, unintelligent, and unproductive. It is an emotional prejudice or discrimination against people based solely on age. Ageism allows the young to separate themselves physically and emotionally from the old and to view older adults as somehow having less human value. Like sexism or racism, ageism is a negative belief pattern that can result in irrational thoughts and destructive behaviors such as intergenerational conflict and name-calling. Like other forms of prejudice, ageism occurs because of myths and stereotypes about a group of people who are different from ourselves.

The combination of societal stereotyping and a lack of positive personal experiences with the elderly affects a cross section of society. Many studies have shown that health care providers share the views of the general public and are not immune to ageism. Few of the “best and brightest” nurses and physicians seek careers in geriatrics despite the increasing need for these services. They erroneously believe that they are not fully using their skills by working with the aging population. Working in intensive care, the emergency department, or other high technology areas is viewed as exciting and challenging. Working with the elderly is viewed as routine, boring, and depressing. As long as negative attitudes such as these are held by health care providers, this challenging and potentially rewarding area of service will continue to be underrated, and the elderly will suffer for it.

Ageism can have a negative effect on the way health care providers relate to older patients, which, in turn, can result in poor health care outcomes in these individuals. Research by the National Institute on Aging reports that (1) older patients receive less information than do younger patients with regard to resources, health management, and illness management; (2) less information is provided to older adults on lifestyle changes such as weight reduction and smoking cessation; (3) limited rehabilitation is available for older adults with chronic disease, despite studies demonstrating that individuals older than 85 years do benefit from rehabilitation programs; and (4) only 47% of physicians feel that older adults should receive the same evaluation and treatment for acute illness as their younger counterparts.

Because an increasing portion of the population consists of older adults, health care providers need to do some soul searching with regard to their own attitudes. Furthermore, they must confront signs of ageism whenever and wherever they appear. Activities such as increased positive interactions with older adults and improved professional training designed to address misconceptions regarding aging are two ways of fighting ageism. The Nursing Competence in Aging (NCA) initiative, which was started in 2002, focuses on enhancing competence in geriatrics by expanding nurses’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes. Research coming from this initiative can help nurses regardless of their area of practice. Becca Levy, a Yale University professor, found that young people who hold positive feelings toward the elderly live 7.5 years longer than those with negative perceptions of aging. On a purely self-serving basis, health care providers should work to stamp out ageism.

Age discrimination reaches beyond emotions and leads to actions. Age discrimination results in different treatment of older people simply because of their age. Refusing to hire older persons, barring them from approval for home loans, and limiting the types or amount of health care they receive are all examples of discrimination that occur despite laws prohibiting them. Some older individuals respond to age discrimination with a passive acceptance, whereas others are banding together to speak up for their rights.

The reality of getting old is that no one knows what it will be like until it happens. But that is the nature of life—growing older is just the continuation of a process that started at birth. Older adults are fundamentally no different from the people they were when they were younger. Physical, financial, social, and political conditions may change, but the person remains essentially the same. Old age has been described as the “more-so” stage of life because some personality characteristics may appear to amplify. Old people are not a homogeneous group. They differ as widely as any other age group. They are unique individuals with unique values, beliefs, experiences, and life stories. Because of their extended years, their stories are longer and often far more interesting than those of younger persons.

Aging can be a freeing experience. Aging seems to decrease the need to maintain pretenses, and the older adult may finally be comfortable enough to reveal the real person that has existed beneath the facade. If a person has been essentially kind and caring throughout life, he or she will generally reveal more of these positive personal characteristics as time marches on. Likewise, if a person was miserly or unkind, he or she will often reveal more of these negative personality characteristics as he or she grows older. The more successful a person has been at meeting the developmental tasks of life, the more likely he or she will successfully face aging. Perhaps the best advice to all who are preparing for old age is contained in the Serenity Prayer:

O God, give us the serenity to accept what cannot be changed; courage to change what should be changed; and wisdom to distinguish one from the other.

Reinhold Niebuhr

Demographics

Demographics is the statistical study of human populations. Demographers are concerned with a population’s size, distribution, and vital statistics. Vital statistics include birth, death, age at death, marriage(s), race, and many other variables. The collection of demographic information is an ongoing process. The most inclusive demographic research in the United States is compiled every 10 years by the Bureau of the Census. The most recent census was completed in the year 2010. It will take some time for the full analysis of these data to be compiled.

Demographic research is important to many groups. Demographic information is used by the government as a basis for granting aid to cities and states, by cities to project their budget needs for schools, by hospitals to determine the number of beds needed, by public health agencies to determine the immunization needs of a community, and by marketers to sell products. The politicians of the 1930s used demographics to formulate plans for the Social Security program. Demographic studies provide information about the present that allows projections into the future.

One important piece of demographic information is life expectancy. Life expectancy is the number of years an average person can expect to live. Projected from the time of birth, life expectancy is based on the ages of all people who die in a given year. If a large number of infants die at birth or during childhood, the life expectancy of that year’s group tends to be low. The life expectancy throughout history has been low because of environmental hazards, wars, accidents, food and water scarcity, inadequate sanitation, and contagious diseases.

Since the beginning of the twentieth century, advances in technology and health care have dramatically changed the world, especially in industrialized nations where food production exceeds the needs of the population. Diseases such as cholera and typhoid have been eliminated or significantly reduced by improved sanitation and hygiene practices. Dreaded communicable diseases that at one time were often fatal (e.g., smallpox, measles, whooping cough, and diphtheria) are now preventable through immunization. Even pneumonia and influenza are no longer the fatal diseases they once were. Today, vaccines can be given to those who are at higher risk, and treatment can be given to those who become infected. It is hoped that changes in the geopolitical climate of the world will lessen the number of deaths resulting from war.

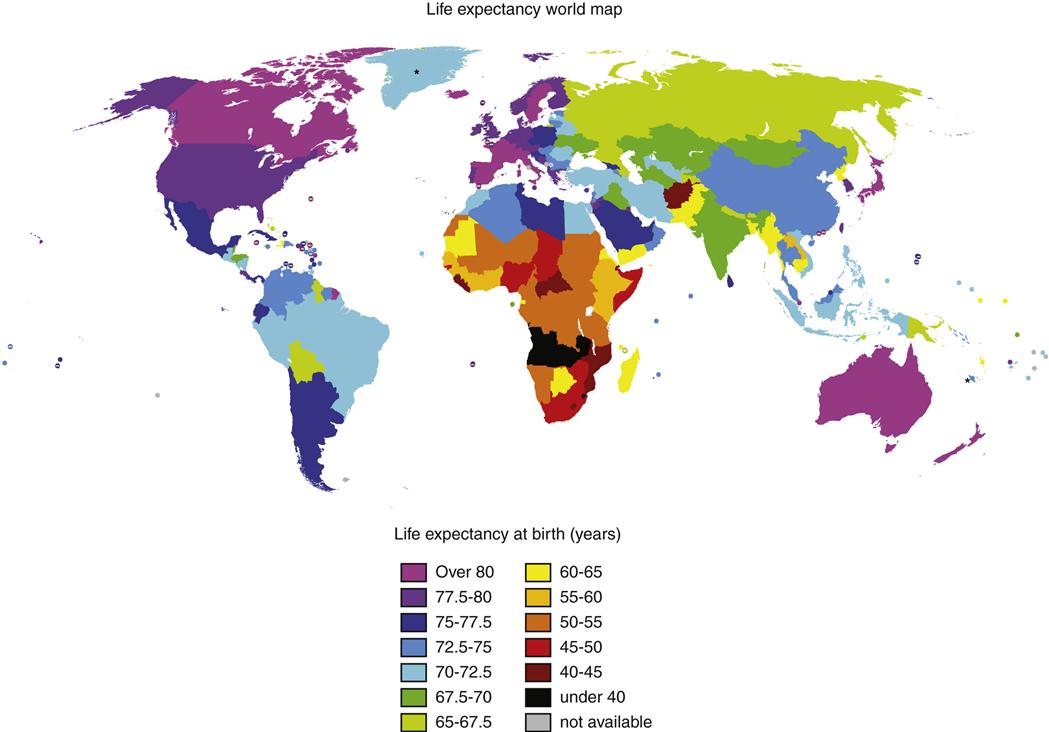

A longer life is a worldwide phenomenon. Almost 8% of the world’s population is age 65 or older. Developed countries, including Japan, Australia, Canada, and Sweden, lead the world in longevity statistics. Germany, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Norway, and France, including Jordan and South Korea, exceed the United States. The standing of the United States has declined over the last few decades, and the United States now ranks 49th among countries with large percentages of senior citizens. Some possible explanations for the disparity between the United States and other countries include higher levels of accidental and violent deaths, obesity, relatively high infant mortality, and the high cost of health care. Much of the world’s net gain in older persons has occurred in the still-developing countries in Africa, South America, and Asia (Figure 1-1).

Scope of the Aging Population

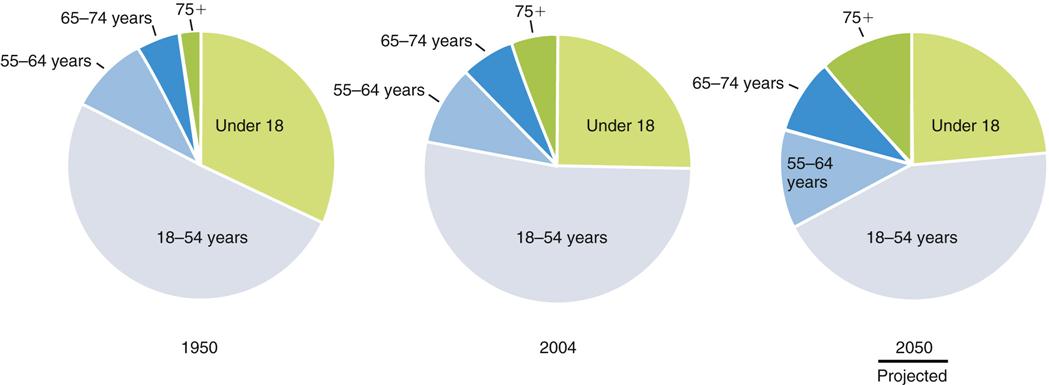

According to the U.S. Department of State, for the first time in recorded history, the number of people over age 65 is projected to exceed the number of children under age 5. In 2008, an estimated 39 million people, or 1 out of 8 people, age 65 or older, lived in the United States. By 2050, this is expected to increase to 72 million people age 65 or older. This is 1 out of 5, or about 20% of the total population of the United States. Individuals older than 85 years now make up 4% of the entire U.S. population and represent the fastest-growing segment of the older population. We are becoming an increasingly older society (Figure 1-2).

Gender and Ethnic Disparity

The Administration on Aging projects that minority populations will represent 26.4% of the older population by 2030, an increase from 16% in 2000. It is projected that by 2030, the white non-Hispanic population will increase by 77%. During the same time period, the percentage of minority persons of the same age cohort is expected to grow by 223% (Hispanics, 342%; African Americans, 164%; American Indians, Eskimos, and Aleuts, 207%; and Pacific Islanders, 302%).

The life expectancy is variable within the U.S. population. The populations of men and women are not equal, and in the older-than-65 age group, this disproportion is very noticeable. There are 22.4 million older women to 16.5 million older men. Women currently outlive men by approximately 7 years. Women tend to live longer than men, and whites tend to live longer than blacks, although disparities seem to be declining.

White women have the longest life expectancy, about 81 years. Black women have a life expectancy of about 76.9 years; white men, 76 years; and black men, 70 years. Because of the lack of precision in defining a Hispanic status (surname, country of origin, etc.), statistics for a Hispanic life expectancy are unclear and often contradictory. Some studies show Hispanics living longer than other groups, whereas other studies show shorter life spans. This is sometimes called the Hispanic Paradox.

In 2008, almost 20% of those over age 65 were identified as minorities. Approximately 9% were black, 3% Asian, and 7% Hispanic of any race. It is projected that by 2050 the population will be almost 40% minority: 20% Hispanic, 12% black, and 9% Asian.

The Baby Boomers

A major contributing factor to this rapid explosion in the elderly is the aging of the cohort, commonly called the Baby Boomers. Age cohort is a term used by demographers to describe a group of people born within a specified time period. The most significant cohort today is the group known as Baby Boomers. This cohort consists of people who were born after World War II between 1946 and 1964. Baby Boomers account for approximately one-third of all Americans today. Because of its size, this group has had, and will continue to have, a significant influence in all areas of society. It remains to be seen whether this group will experience aging in the same way that previous generations have experienced changes or whether they will reinvent the aging and retirement experience. The oldest Baby Boomers are now in their sixties. The oldest reached age 65 in 2011. By 2029 all Baby Boomers will be age 65 or older. Based on the sheer size of this group, the older population in 2030 will be twice the number it was in 2000. The implications of this for all areas of society, particularly health care, are unprecedented.

Geographic Distribution of the Elderly Population

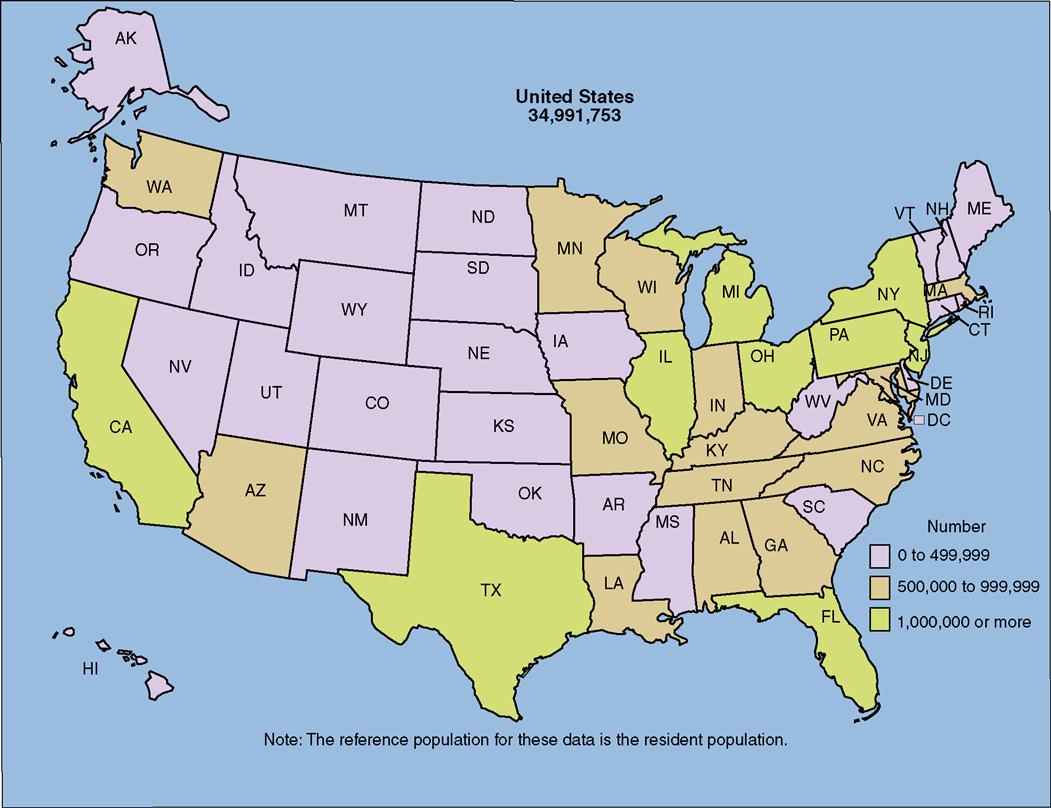

The older adult population is not equally distributed throughout the United States. Climate, taxes, and other issues regarding the quality of life influence where older adults choose to live. All regions of the country are affected by the increases in life expectancy, but not to the same degree. According to census data from the year 2000, approximately half of the older-than-65 population reside in nine states only. In descending order of the older adult population, the nine states are California (more than 3.8 million); Florida, New York, and Texas (more than 2 million each); Pennsylvania (1.9 million); and Ohio, Illinois, Michigan, and New Jersey (more than 1 million each). Population distribution data show that Florida leads the nation, with 17% of its population being older than 65 years. Eleven states, including Nevada, Alaska, Hawaii, Arizona, Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, Wyoming, Delaware, North Carolina, and Texas, have shown a rapid increase in the older-than-65 population. Approximately 78% of older adults reside in metropolitan areas, with approximately 27% residing in the central city. Only 23% of older adults reside in nonmetropolitan areas (Figure 1-3).

Statistical evaluation of minority populations reveals that groups tend to concentrate in a limited number of states. Half of elderly blacks live in New York, Florida, California, Texas, Georgia, North Carolina, Illinois, and Virginia; 70% of the Hispanic elderly live in California, Texas, Florida, and New York; and 60% of elderly persons of Asian, Hawaiian, or Pacific Island descent favor California, Hawaii, and New York. The majority of elderly people of Native American or Native Alaskan descent live in California, Oklahoma, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and North Carolina.

Marital Status

In 2008 three-fourths (75%) of men over age 65 were married compared to 57% of older women. The percentage of married individuals drops significantly as age progresses, but the percentage of the oldest old men who are married remains high at 55%. At age 65, 42% of women were widows compared with only 14% of men. By age 85, 76% of women were widows compared to only 38% of men. The percentage of older adults who are separated or divorced has increased significantly to 11%. An increase in the number of divorced elders is predicted as a result of a higher incidence of divorce in the population approaching age 65.

The number of single, never-married seniors remains somewhat consistent at about 4% of the older-than-65 population.

Educational Status

The educational level of the older adult population in the United States has changed dramatically over the past three decades. In 1970, only 28% of senior citizens had graduated from high school. By 2008, 78% were high school graduates or more, and 21% had a bachelor’s degree or higher. Twenty-seven percent of older men hold bachelor’s degrees as contrasted with 16% of older women.

In addition to being better educated, today’s older adult population is more technologically sophisticated. A Pew research study conducted in 2004 revealed that 23% of Americans over age 65 use the Internet. In 2006 the same group reported that Internet use among Americans over age 65 had increased to 34%, and by 2008 had further increased to 43%. This will most likely continue to increase in the near future because, as of 2009, more than 77% of Baby Boomers have reported that they are Internet users.

Economics of aging

The stereotypical belief that many older adults are poor is not necessarily true. The economic status of older persons is as varied as that of other age groups. Some of the poorest people in the country are old, but so are some of the richest.

Poverty

In 2007 approximately 10% of the elderly population was statistically determined to be at or below the poverty level. Older women were more likely to be impoverished than older men. Those over age 75 were slightly more likely to experience poverty. Elderly minorities, particularly blacks, were slightly more likely to live in poverty. Although they have declined over time, as of 2008, poverty rates are still highest in the South. Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama, Arkansas, Tennessee, New Mexico, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia have poverty rates in excess of 17%. Of the remaining elderly, 26% were statistically determined to have a low-income status, 33% were in the middle-income range, and 31% had a high-income status.

Income

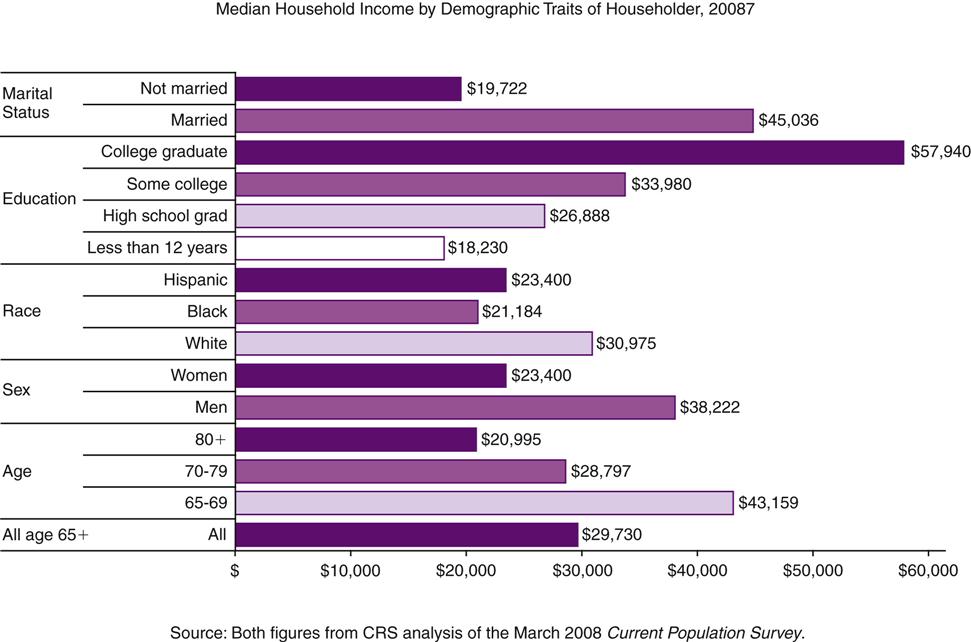

As of 2007 the median income of men over age 65 was $24,142, whereas that for women over age 65 was $13,877 only. The median income of households headed by a person 65 years of age or older was approximately $43,159. Median income is the middle of the group with half earning less and half earning more. It is not an average amount. Median figures can be deceptive because income is not distributed equally among whites and minority groups (Figure 1-4).

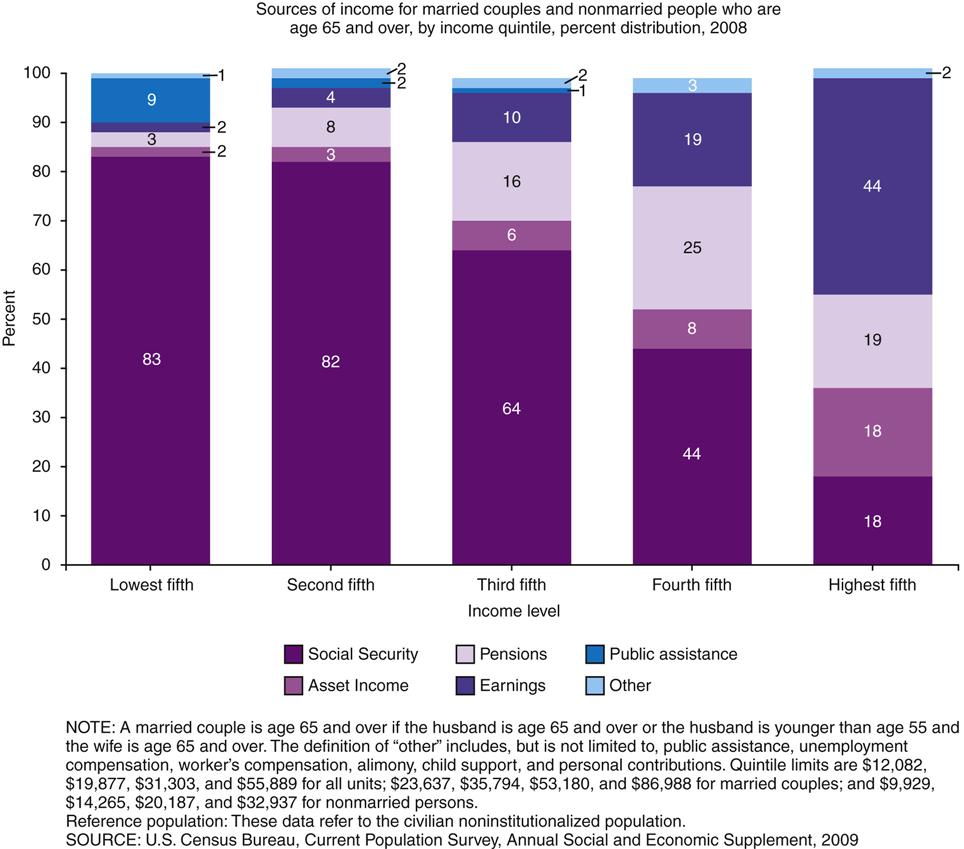

The major sources of aggregate income for older adults include Social Security benefits earnings, asset income, pensions, earnings from employment, public assistance, and miscellaneous sources. Figure 1-5 shows the sources of income for five different income levels (income quintiles).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree