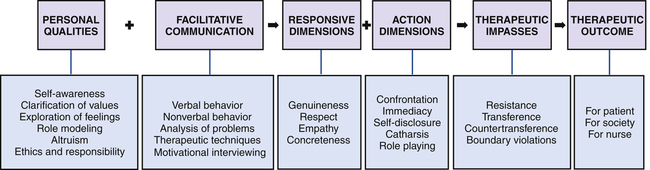

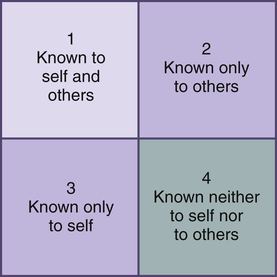

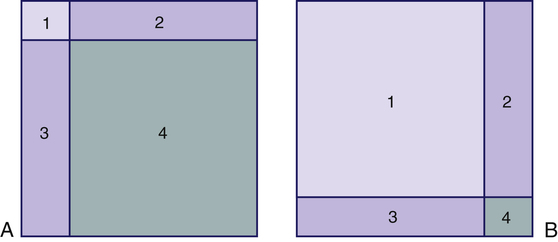

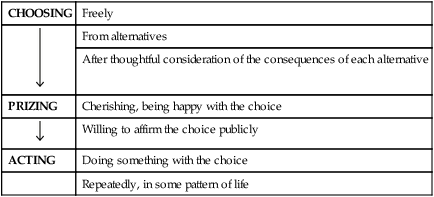

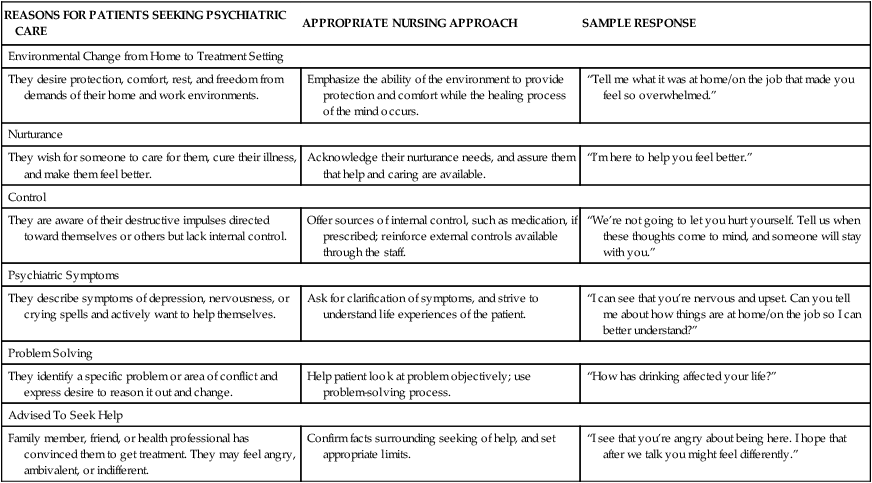

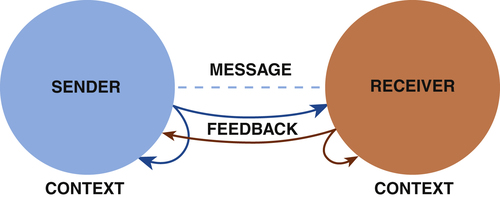

1. State the goals of the therapeutic nurse–patient relationship. 2. Discuss six personal qualities a nurse needs to be an effective helper. 3. Describe the nurse’s tasks and possible problems in the four phases of the relationship process. 4. Examine the levels of communication, the communication process, therapeutic communication techniques, and motivational interviewing. 5. Analyze how the nurse uses each of the responsive dimensions in a therapeutic relationship. 6. Analyze how the nurse uses each of the action dimensions in a therapeutic relationship. 7. Evaluate therapeutic impasses, and identify nursing interventions to deal with them. 8. Demonstrate increasing effectiveness in using therapeutic relationship skills to produce a therapeutic outcome. The therapeutic nurse–patient relationship is a mutual learning experience and a corrective emotional experience for the patient. It is based on the humanity of the nurse and patient, mutual respect, and acceptance of sociocultural differences. In this relationship the nurse uses personal qualities and clinical skills in working with the patient to effect insight and behavioral change. Most importantly, the core of mental health nursing is providing hope for a better future to patients and their families (Stuart, 2010). • Enhanced self-realization, self-acceptance, and increased self-respect • A clear sense of personal identity and an improved level of personal integration • The ability to form intimate, interdependent, interpersonal relationships with a capacity to give and receive love • Improved functioning and increased ability to satisfy needs and achieve realistic personal goals To achieve these goals, various aspects of the patient’s life experiences are explored. The nurse allows the patient to express thoughts and feelings and relates these to observed and reported behaviors, clarifying areas of conflict and anxiety. The nurse identifies and maximizes the patient’s ego strengths and encourages socialization and family relatedness. Together the patient and nurse correct communication problems and modify maladaptive behavior patterns by testing new patterns of behavior and more adaptive coping mechanisms (Wheeler, 2011). In the nurse-patient relationship, differing values are respected. The two communicate through a dialogue or discussion, affirming the patient’s reality and worth and allowing the patient to more fully define ego identity. Rogers (1961) summarizes the characteristics of a helping relationship that facilitate growth (Box 2-1). All nurses working with patients should ask themselves these questions because the answers will determine the progress of the relationship. The therapeutic nurse-patient relationship is complex, but evidence shows that a strong therapeutic alliance has a positive effect on patient outcomes (Norcross et al, 2006; Miner-Williams, 2007). This chapter examines the personal qualities of the nurse as helper, the phases of the relationship, facilitative communication, responsive and action dimensions, therapeutic impasses, and therapeutic outcomes (Figure 2-1). Each of these factors influences the nurse’s effectiveness. Effective helpers must be able to answer the question, Who am I? Nurses who care for the biological, psychological, and sociocultural needs of patients see a broad range of human experiences. They must learn to deal with anxiety, anger, sadness, and joy in helping patients throughout the health-illness continuum. Self-awareness is a key part of the psychiatric nursing experience, and the nurse’s goal is to achieve authentic, open, and personal communication (LaTorre, 2005; Vandemark, 2006; Scheick, 2011). The nurse must be able to examine personal feelings, actions, and reactions. A good understanding and acceptance of self allow the nurse to acknowledge a patient’s differences and uniqueness. A holistic nursing model of self-awareness consists of four interconnected components: psychological, physical, environmental, and philosophical (Campbell, 1980): 1. The psychological component includes knowledge of emotions, motivations, self-concept, and personality. Being psychologically self-aware means being sensitive to feelings and outside events that affect those feelings. 2. The physical component is the knowledge of personal and general physiology, as well as of body sensations, body image, and physical potential. 3. The environmental component consists of the sociocultural environment, relationships with others, and knowledge of the relationship between humans and nature. 4. The philosophical component is the sense of life having meaning. A personal philosophy of life and death may or may not include a spiritual being, but it does take into account responsibility to the world and the ethics of behavior. No one ever completely knows the inner self, as shown in the Johari window (Figure 2-2). • Quadrant 1 is the open quadrant; it includes the behaviors, feelings, and thoughts known to the individual and others. • Quadrant 2 is the blind quadrant; it includes all the things that others know but the individual does not know. • Quadrant 3 is the hidden quadrant; it includes the things about the self that only the individual knows. • Quadrant 4 is the unknown quadrant, containing aspects of the self that are unknown to the individual and to others. 1. A change in any one quadrant affects all other quadrants. 2. The smaller quadrant 1, the poorer the communication. 3. Interpersonal learning means that a change has taken place, so quadrant 1 is larger and one or more of the other quadrants is smaller. Compare panels A and B of Figure 2-3. Panel A represents a person with little self-awareness whose behaviors and feelings are limited. Panel B, however, shows an individual with great openness to the world. Much of this person’s potential is being developed and realized. Panel B represents an individual who has an increased capacity for experiences of all kinds: joy, hate, work, and love. This person also has few defenses and can interact more spontaneously and honestly with others. It is a worthy goal for the nurse to pursue. Values are concepts that are formed as a result of life experiences with family, friends, culture, education, work, and relaxation. The word value has positive connotations of worth or significance, but values also can imply negatives. If we value honesty, then it follows that we do not value dishonesty. People are likely to hold strong values related to religious beliefs, family ties, sexual preferences, other ethnic groups, and gender role beliefs. One of the many challenges facing nurses today is the need to provide care for patients from diverse backgrounds. Because the goals of treatment are determined greatly by beliefs and values, establishing a therapeutic relationship with patients from different backgrounds requires particular skill and sensitivity. This is discussed in Chapter 7. Seven criteria are used to determine a value. These criteria should be considered in relation to a person’s strongest value and tested against the person’s own definition of a value. The seven criteria are grouped into the three steps listed in Table 2-1. The three criteria of choosing rely on the person’s cognitive abilities; the two criteria of prizing emphasize the emotional or affective level; and the two criteria of acting have a behavioral focus. A change takes place when certain contradictions are perceived in the person’s value system. To eliminate the distress that follows such a realization, the person realigns values to coincide with the new view of self. TABLE 2-1 STEPS IN THE VALUE CLARIFICATION PROCESS The valuing process in the mature person is complex, and the choices are often difficult. There is no guarantee that the choice made will be self-actualizing. The valuing process in the mature person has the following characteristics (Kirschenbaum and Simon, 1973): • It is fluid and flexible, based on the particular moment and the degree to which the moment is enhancing, enriching, and actualizing. Values are continually changing. • The valuing experience is tied to a particular time and experience. • Personal experience provides the value information. Although the person is open to all evidence obtained from other sources, outside evidence is not considered as important as subjective responses. The psychologically mature adult trusts and uses personal wisdom. • In the valuing process the person is open to the immediacy of experience, trying to sense and clarify all its complex meanings. However, the immediate impact of the moment is colored by experiences from the past and thoughts about the future. Personal beliefs about people and society can serve as guidelines for action. The Code for Nurses with Interpretive Statements (American Nurses Association, 2001) reflects common values regarding nurse-patient relationships and responsibilities and serves as a frame of reference for all nurses in their judgments about patient welfare and social responsibility. Responsible ethical choice involves accountability, risk, commitment, and justice. Related to the nurse’s sense of ethics is the need to assume responsibility for one’s own behavior. This means knowing one’s limitations and strengths and being accountable for them. Ethical issues related to psychiatric nursing are discussed in Chapter 8. A vital characteristic of the nurse-patient relationship is the sharing of behaviors, thoughts, and feelings that is based on clear role expectations. The support requested and provided should be within the boundaries of the nurse’s role as a professional caregiver. The elements of a therapeutic nurse-patient relationship apply to all clinical settings and can be adapted to settings in which the patient is only seen for a brief period of time (Spiers and Wood, 2010). Nurses working in medical, surgical, obstetrical, oncological, and other specialty areas need to understand and be able to use therapeutic nurse-patient relationship skills. Four phases of the nurse-patient relationship have been identified: preinteraction phase; introductory, or orientation, phase; working phase; and termination phase. Each phase builds on the preceding one and has specific tasks. The preinteraction phase begins before the nurse’s first contact with the patient. The nurse’s initial task is one of self-exploration. This is no small task because psychiatric nursing clinical experience can bring both stress and challenge to the student (Happell and Gough, 2009). In the first experience of working with psychiatric patients, the nurse brings the misconceptions and prejudices of the general public, in addition to feelings and fears common to all novices (Halter, 2008; Webster, 2009) (Box 2-2). A major one is anxiety or nervousness, which is common to new experiences of any kind. Another feeling is ambivalence or uncertainty because nurses may see the need for working with these patients but feel uncertain about their ability to do so. Experienced nurses benefit by asking themselves the following questions: • Do I label patients with the stereotype of a group? • Is my need to be liked so great that I become angry or hurt when a patient is rude, hostile, or uncooperative? • Am I afraid of the responsibility I must assume for the relationship? • Do I cover feelings of inferiority with a front of superiority? • Do I require sympathy, warmth, and protection so much that I become too sympathetic or too protective toward patients? • Do I fear closeness so much that I am indifferent, rejecting, or cold? • Do I need to feel important and keep patients dependent on me? It is during the introductory phase that the nurse and patient first meet. One of the nurse’s primary concerns is to find out why the patient sought help (Table 2-2). The reason for seeking help forms the basis of the nursing assessment, helps the nurse focus on the patient’s problem, and determines the patient’s motivation for treatment. It is important for the nurse to realize that help-seeking varies among different cultures, social, and ethnic groups. Another task is for the patient and nurse to establish their partnership and agree on the nature of the problem and the patient’s treatment goals. The focus is on the patient’s goals and not what the nurse believes should be done. Both the nurse and the patient may experience some degree of discomfort and nervousness in the introductory phase. Reasons that patients may have difficulty receiving help are listed in Box 2-3. TABLE 2-2 ANALYSIS OF WHY PATIENTS SEEK PSYCHIATRIC HELP Modified from Burgess A, Burns J: Am J Nurs 73:314, 1973. The tasks in this phase of the relationship are to establish a climate of trust, understanding, acceptance, and open communication and formulate a contract with the patient. Establishing a contract is a mutual process in which the patient participates as fully as possible. Box 2-4 lists the elements of a nurse-patient contract. The contract begins with the introduction of the nurse and patient, exchange of names, and explanation of roles. An explanation of roles includes the responsibilities and expectations of the patient and nurse, with a description of what the nurse can and cannot do. This is followed by a discussion of mutually agreed on specific goals, in which the nurse focuses on what the patient identifies as important problems to be resolved. Because establishing the contract is a mutual process, it is a good opportunity to clarify misperceptions held by either the nurse or the patient. The issue of confidentiality is an important one to discuss with the patient at this time. Confidentiality involves the disclosure of certain information only to another specifically authorized person (Chapter 8). This means that information about the patient will be shared only with people who are directly involved in the patient’s care in the form of verbal reports and written notes. This is important in providing for the continuity and comprehensiveness of patient care and should be clearly explained to the patient. Termination is one of the most difficult but most important phases of the therapeutic nurse-patient relationship. It is a time to exchange feelings and memories and to evaluate mutually the patient’s progress and goal attainment. Levels of trust and intimacy are heightened, reflecting the quality of the relationship and the sense of loss experienced by both nurse and patient. Box 2-5 lists criteria that can be used to determine whether the patient is ready to terminate. Learning to bear the sorrow of the loss while integrating positive aspects of the relationship into one’s life is the goal of termination for both the nurse and the patient. The patient’s response will be affected by the nurse’s ability to remain open, sensitive, empathic, and responsive to the patient’s changing needs. The impending termination can be as difficult for the nurse as for the patient. Nurses who can begin this process by reviewing their thoughts, feelings, and experiences will be more aware of personal motivation and more responsive to patients’ needs. The major tasks of the nurse during each phase of the nurse-patient relationship are summarized in Table 2-3. TABLE 2-3 NURSE’S TASKS IN EACH PHASE OF THE RELATIONSHIP PROCESS Communication, which takes place on two levels (verbal and nonverbal), can either facilitate the development of a therapeutic relationship or serve as a barrier to it (Shattell and Hogan, 2005; Sheldon et al, 2006). Everyone communicates constantly from birth until death. All behavior is communication, and all communication affects behavior. Communication is critical to nursing practice because of the following: • Communication is the vehicle used to establish a therapeutic relationship. Without it, a therapeutic nurse-patient relationship is not possible. • Communication is the means by which people influence the behavior of another, leading to the successful outcome of nursing intervention. • Intimate space: up to 18 inches. This small degree of separation between people allows for maximal interpersonal sensory stimulation. • Personal space: 18 inches to 4 feet. This zone is used for close relationships and when touching distance may be desired. • Social-consultative space: 9 to 12 feet. This zone is less personal; it requires that speech be louder. • Public space: 12 feet and more. This is used in speech giving and other large gatherings. Theoretical models of the communication process show visual relationships more clearly and can help in finding and correcting communication breakdowns or problems. The structural model of communication has five components: the sender, the message, the receiver, the feedback, and the context (Figure 2-4):

Therapeutic Nurse–Patient Relationship

Characteristics of the Relationship

Personal Qualities of the Nurse

Awareness of Self

Increasing Self-Awareness

Clarification of Values

Value Systems

Value Clarification Process

CHOOSING

Freely

From alternatives

After thoughtful consideration of the consequences of each alternative

PRIZING

Cherishing, being happy with the choice

Willing to affirm the choice publicly

ACTING

Doing something with the choice

Repeatedly, in some pattern of life

The Mature Valuing Process

Ethics and Responsibility

Phases of the Relationship

Preinteraction Phase

Concerns of New Nurses

Self-Assessment

Introductory, or Orientation, Phase

REASONS FOR PATIENTS SEEKING PSYCHIATRIC CARE

APPROPRIATE NURSING APPROACH

SAMPLE RESPONSE

Environmental Change from Home to Treatment Setting

They desire protection, comfort, rest, and freedom from demands of their home and work environments.

Emphasize the ability of the environment to provide protection and comfort while the healing process of the mind occurs.

“Tell me what it was at home/on the job that made you feel so overwhelmed.”

Nurturance

They wish for someone to care for them, cure their illness, and make them feel better.

Acknowledge their nurturance needs, and assure them that help and caring are available.

“I’m here to help you feel better.”

Control

They are aware of their destructive impulses directed toward themselves or others but lack internal control.

Offer sources of internal control, such as medication, if prescribed; reinforce external controls available through the staff.

“We’re not going to let you hurt yourself. Tell us when these thoughts come to mind, and someone will stay with you.”

Psychiatric Symptoms

They describe symptoms of depression, nervousness, or crying spells and actively want to help themselves.

Ask for clarification of symptoms, and strive to understand life experiences of the patient.

“I can see that you’re nervous and upset. Can you tell me about how things are at home/on the job so I can better understand?”

Problem Solving

They identify a specific problem or area of conflict and express desire to reason it out and change.

Help patient look at problem objectively; use problem-solving process.

“How has drinking affected your life?”

Advised To Seek Help

Family member, friend, or health professional has convinced them to get treatment. They may feel angry, ambivalent, or indifferent.

Confirm facts surrounding seeking of help, and set appropriate limits.

“I see that you’re angry about being here. I hope that after we talk you might feel differently.”

Forming a Contract

Termination Phase

PHASE

TASK

Preinteraction

Explore own feelings, fantasies, and fears

Analyze own professional strengths and limitations

Gather data about patient when possible

Plan for first meeting with patient

Introductory,

Determine why patient sought help

or orientation

Establish trust, acceptance, and open communication

Mutually formulate a contract

Explore patient’s thoughts, feelings, and actions

Identify patient’s problems

Define goals with patient

Working

Explore relevant stressors

Promote patient’s development of insight and use of constructive coping mechanisms

Overcome resistance behaviors

Termination

Establish reality of separation

Review progress of therapy and attainment of goals

Mutually explore feelings of rejection, loss, sadness, and anger and related

behaviors

Facilitative Communication

Nonverbal Communication

Types of Nonverbal Behaviors

The Communication Process

Structural Model

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Therapeutic Nurse–Patient Relationship

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access