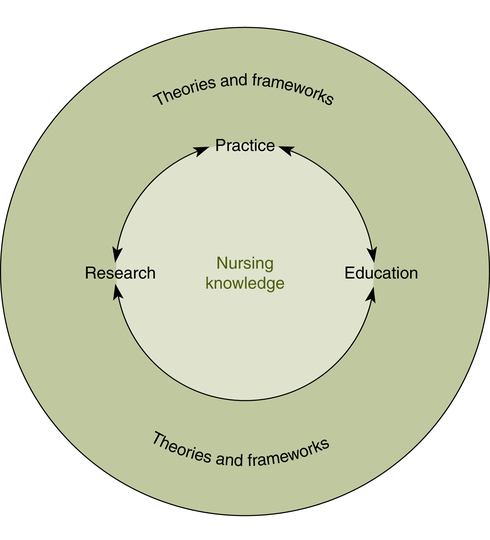

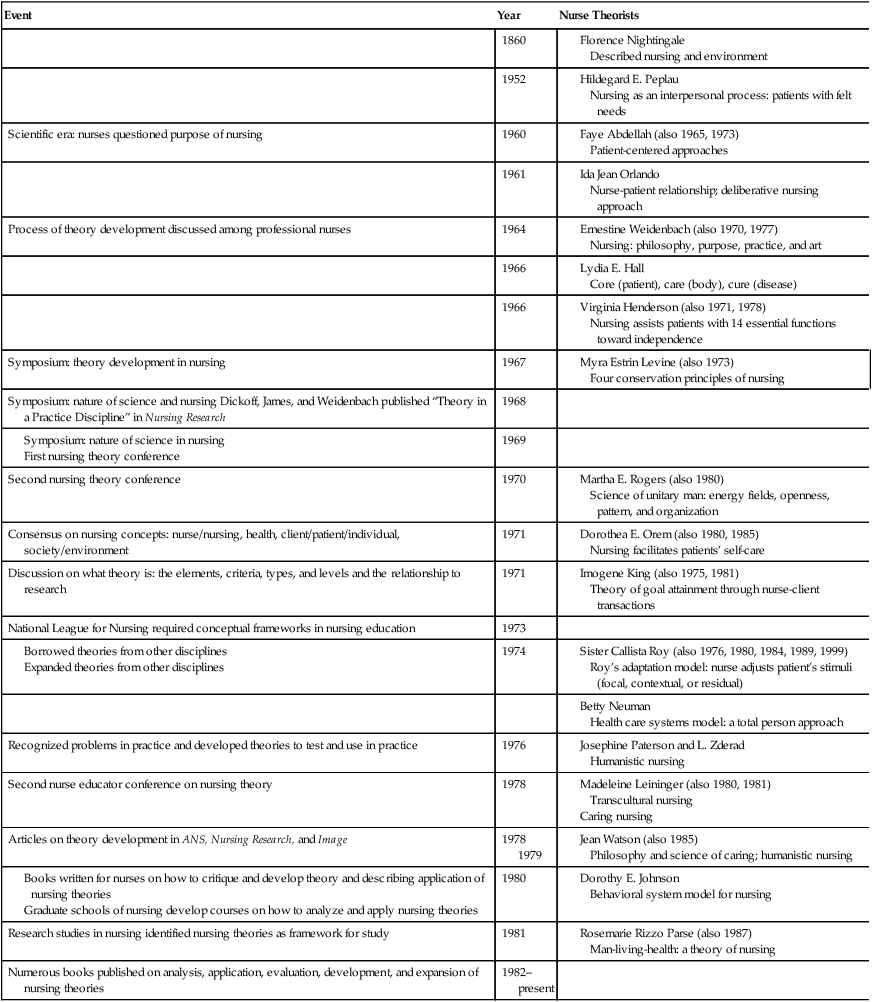

At the completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Distinguish among a concept, a theory, a conceptual framework, and a model. • Identify and define the four central concepts of nursing theories. • Compare the main precepts of selected theories of nursing. • Examine criteria for evaluating the utility of a specific nursing theory for its relevance to practice, education, or research. • Identify selected theories from related disciplines that have application to nursing. Theory is the poetry of science. The poet’s words are familiar, each standing alone, but brought together they sing, they astonish, they teach. (Levine, 1995, p. 14) Nursing is both a science and an art. The empirical science of nursing includes both the natural sciences (e.g., biology, chemistry) and the human sciences (e.g., sociology, psychology). The art of nursing is the ability to form trusting relationships, perform procedures skillfully, prescribe appropriate treatments, and morally conduct nursing practice (Johnson, 1994). Nursing is a knowledge-based discipline significantly different from medicine. Medicine focuses on the identification and treatment of disease, whereas nursing focuses on the wholeness of human beings (Fawcett, 1993). Nursing claims the health of human beings in interaction with the environment as its domain. Knowledge is commonly defined as a general awareness or possession of information, facts, ideas, truths, or principles and an understanding of the same gained through experience or study (Encarta World English Dictionary, 2009). Nursing knowledge is the organization of the discipline-specific concepts, theories, and ideas published in the literature (both print and electronic media) and demonstrated in professional practice. Nursing’s desire to be regarded as a profession (e.g., law, medicine) was the impetus for building a substantial body of discipline-specific knowledge. Many of the existing theories emerged from the response to the simple question, “What is nursing?” Theories and conceptual frameworks consist of the theorist’s words brought together to form a meaningful whole. Theories and frameworks provide direction and guidance for structuring professional nursing practice, education, and research. They act as a “tool for reasoning, critical thinking, and decision-making” (Alligood, 2005, p. 272). In practice, theories and frameworks help nurses describe, explain, and predict everyday experiences. They also assist in organizing assessment data, making diagnoses, choosing interventions, and evaluating nursing care. In education, a conceptual framework provides the general focus for curriculum design. In research, the framework offers a systematic approach to identifying questions for study, selecting appropriate variables, and interpreting findings. The research findings may trigger revision and refinement of the theory. Figure 5-1 illustrates the relationships among theory, practice, education, and research. Many nurse theorists have made substantial contributions to the development of a body of nursing knowledge. Offering an assortment of perspectives, the theories vary in their level of abstraction and their conceptualization of the client, health and illness, the environment, and nursing. From a historical perspective, nursing theories reflect the influence of the larger society and illustrate increased sophistication in the development of nursing ideas. Table 5-1 presents a chronology of events related to the development of nursing theories. While this chapter provides a comprehensive overview of nursing theory, other chapters in this text will make reference to specific nursing theories as they relate to individual chapter topics. TABLE 5-1 History of Nursing Theory Development Modified from Christensen, P. J., & Kenney, J. W. (1995). Nursing process: Application of conceptual models. (4th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby. The most fundamental building block of a theory is a concept, which is defined as “a word or phrase that summarizes ideas, observations, and experiences” (Fawcett, 2005, p. 4). For a theory to exist, concepts must be related to one another. Theoretical statements, also called propositions, describe a concept or the relationship between two or more concepts (Fawcett, 2005). One theoretical statement, or several theoretical statements taken together, can constitute a theory. A theory, then, is a statement or a group of statements that describe, explain, or predict relationships among concepts. A nursing theory is composed of a set of concepts and propositions that claims to account for or characterize the central phenomena of interest to the discipline of nursing: person, environment, health/illness, and nursing. Persons are the recipients of nursing care and include individuals, families, and communities. Environment refers to the surroundings of the client, internal factors affecting the client, and the setting where nursing care is delivered. Health and illness describe the client’s state of well-being. Nursing refers to the actions taken when providing care to a patient. These concepts, taken together, make up what is known as the metaparadigm of nursing (Fawcett, 1997). Most nursing theories define or describe these central concepts, either explicitly or implicitly. Because a concept is an abstract representation of the real world, concepts embedded in a theory represent the theorist’s perspective of reality and may differ from that of the reader without invalidating the theory. Theories represent abstract ideas rather than concrete facts (Alligood, 2005) and may be broad or limited in scope, thus varying in their ability to describe, explain, or predict. Theories may be categorized by their level of abstraction as grand theories, midrange theories, or practice theories. Grand theories (also known as conceptual models or frameworks) are representations of the broad nature, purpose, and goals of the discipline. Concepts and their relationships are very abstract, not operationally defined, and not empirically testable. Midrange theories, which may be derived from grand theories, are less abstract with relatively concrete concepts that address specific phenomena across nursing settings and specialties. Relationships between and among concepts can be defined explicitly and measured. Because they are narrower in scope, midrange theories appear more applicable to practice and remain abstract enough to allow a wide range of empirical research. Practice theories (sometimes called situation-specific theories) are limited further to a patient population or type of nursing practice (Im & Meleis, 1999; Meleis, 2005). Most practice theories are either descriptive (portraying an experience) or prescriptive (advocating specific nursing actions) in nature. Exploring a variety of nursing theories ought to provide nurses with new insights into patient care, opening nursing options otherwise hidden, and stimulating innovative interventions. But it is imperative that there be variety—for there is no global theory of nursing that fits every situation. (Levine, 1995, p. 13) Environment refers to conditions external to the individual that affect life and development (e.g., ventilation, warmth, light, diet, cleanliness, noise). Nightingale (1860, 1946) identified three major relationships: the environment to the patient, the nurse to the environment, and the nurse to the patient. Examples of these follow: • The need for light, particularly sunlight, is second only to the need for ventilation. If necessary, the nurse should move the patient “about after the sun according to the aspects of the rooms, if circumstances permit, [rather] than let him linger in a room when the sun is off” (Nightingale, 1946, p. 48). • Nursing’s role is to manipulate the environment to encourage healing. Nursing “ought to signify the proper use of fresh air, light, warmth, cleanliness, quiet, and the proper selection and administration of diet” (Nightingale, 1946, p. 6). • The sine qua non of all good nursing is never to allow a patient to be awakened, intentionally or accidentally: “A good nurse will always make sure that no blind or curtains should flap. If you wait till your patient tells you or reminds you of these things, where is the use of their having a nurse?” (Nightingale, 1946, p. 27). • Variety is important for patients to divert them from dwelling on their pain: “Variety of form and brilliancy of color in the objects presented are actual means of recovery” (Nightingale, 1946, p. 34). The individual is a unified, irreducible whole, manifesting characteristics that are more than, and different from, the sum of his or her parts and continuously evolving, irreversibly and unidirectionally along a space–time continuum. Pattern and organization of human beings are directed toward increasing complexity rather than maintaining equilibrium. The individual “is characterized by the capacity for abstraction and imagery, language and thought, sensation and emotion” (Rogers, 1970, p. 73). The environment is an irreducible, pandimensional energy field identified by pattern and integral with the human energy field (Rogers, 1994). The individual and the environment are continually exchanging matter and energy with one another, resulting in changing patterns in both the individual and the environment. Health and illness are value-laden, arbitrarily defined, and culturally infused notions. They are not dichotomous but are part of the same continuum. Health seems to occur when patterns of living are in harmony with environmental change, whereas illness occurs when patterns of living are in conflict with environmental change and are deemed unacceptable (Rogers, 1994). As both a science and an art, nursing is unique in its concern with unitary human beings as synergistic phenomena. The science of nursing should be concerned with studying the nature and direction of unitary human development integral with the environment and with evolving descriptive, explanatory, and predictive principles for use in nursing practice. The new age of nursing science is characterized by a synthesis of fact and ideas that generate principles and theories (Rogers, 1994). The art of nursing is the creative use of the science of nursing for human betterment (Rogers, 1990). The goal of nursing is the attainment of the best possible state of health for the individual who is continually evolving by promoting symphonic interactions between human beings and environments, strengthening the coherence and integrity of the human field, and directing and redirecting patterning of both fields for maximal health potential. • Energy field. The fundamental unit of the living and nonliving. Energy fields are dynamic, continuously in motion, and infinite. They are of two types: • Human energy field: More than the biological, psychological, and sociological fields taken separately or together; an irreducible, indivisible, pandimensional whole identified by pattern and manifesting characteristics that cannot be predicted from the parts. • Environmental energy field: An irreducible, indivisible, pandimensional energy field identified by pattern and integral with the human field. • Openness. Continuous change and mutual process as manifested in human and environmental fields. • Pattern. The distinguishing characteristic of an energy field perceived as a single wave. • Principles of nursing science. Principles postulating the nature and direction of unitary human development; these principles are also called principles of homeodynamics: • Helicy: According to Rogers, helicy is “the continuous, innovative, probabilistic, increasing diversity of human and environmental field patterns characterized by repeating rhymicities” (1989, p. 186). Change occurs continuously. • Resonancy: Rogers describes resonancy as “the continuous change from lower to higher frequency wave patterns in human and environmental fields” (1989, p. 186). Change is increasingly diverse. • Integrality: Replacing the earlier concept of complementarity, integrality is “the continuous mutual human and environmental field process” (Rogers, 1989, p. 186). Field changes occur simultaneously. The foundations of Dorothea Orem’s theory were introduced in the late 1950s, but the first edition of her work Nursing: Concepts of Practice was not published until 1971. Five subsequent editions (1980, 1985, 1991, 1995, 2001) show evidence of continued development and refinement of the theory. Orem focuses on nursing as deliberate human action and notes that all individuals can benefit from nursing when they have health-derived or health-related limitations for engaging in self-care or the care of dependent others. Three theories are subsumed in the self-care deficit theory of nursing: the theory of nursing systems, the theory of self-care deficits, and the theory of self-care (Orem, 2001). Health, which has physical, psychological, interpersonal, and social aspects, is a state in which human beings are structurally and functionally whole or sound (Orem, 1995). Illness occurs when an individual is incapable of maintaining self-care as a result of structural or functional limitations.

Theories and Frameworks for Professional Nursing Practice

![]() Introduction

Introduction

Event

Year

Nurse Theorists

1860

1952

Scientific era: nurses questioned purpose of nursing

1960

1961

Process of theory development discussed among professional nurses

1964

1966

1966

Symposium: theory development in nursing

1967

Symposium: nature of science and nursing Dickoff, James, and Weidenbach published “Theory in a Practice Discipline” in Nursing Research

1968

1969

Second nursing theory conference

1970

Consensus on nursing concepts: nurse/nursing, health, client/patient/individual, society/environment

1971

Discussion on what theory is: the elements, criteria, types, and levels and the relationship to research

1971

National League for Nursing required conceptual frameworks in nursing education

1973

1974

Recognized problems in practice and developed theories to test and use in practice

1976

Second nurse educator conference on nursing theory

1978

Articles on theory development in ANS, Nursing Research, and Image

1978

1979

1980

Research studies in nursing identified nursing theories as framework for study

1981

Numerous books published on analysis, application, evaluation, development, and expansion of nursing theories

1982–present

![]() Terminology Associated with Nursing Theory

Terminology Associated with Nursing Theory

![]() Overview of Selected Nursing Theories

Overview of Selected Nursing Theories

![]() Grand Theory

Grand Theory

NIGHTINGALE’S ENVIRONMENTAL THEORY

Key Concepts

ROGERS’ SCIENCE OF UNITARY HUMAN BEINGS

Assumptions About the Individual

Environment

Health and Illness

Nursing

Key Concepts

OREM’S SELF-CARE DEFICIT THEORY

Health and Illness

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Theories and Frameworks for Professional Nursing Practice

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access