Identify major characteristics of theories, conceptual models, and frameworks

Identify several conceptual models or theories frequently used by nurse researchers

Identify several conceptual models or theories frequently used by nurse researchers

Describe how theory and research are linked in quantitative and qualitative studies

Describe how theory and research are linked in quantitative and qualitative studies

Critique the appropriateness of a theoretical framework—or its absence—in a study

Critique the appropriateness of a theoretical framework—or its absence—in a study

Define new terms in the chapter

Define new terms in the chapter

Key Terms

Conceptual framework

Conceptual framework

Conceptual map

Conceptual map

Conceptual model

Conceptual model

Descriptive theory

Descriptive theory

Framework

Framework

Middle-range theory

Middle-range theory

Model

Model

Schematic model

Schematic model

Theoretical framework

Theoretical framework

Theory

Theory

High-quality studies typically achieve a high level of conceptual integration. This happens when the research questions fit the chosen methods, when the questions are consistent with existing evidence, and when there is a plausible conceptual rationale for expected outcomes—including a rationale for any hypotheses or interventions. For example, suppose a research team hypothesized that a nurse-led smoking cessation intervention would reduce smoking among patients with cardiovascular disease. Why would they make this prediction—what is the “theory” about how the intervention might change people’s behavior? Do the researchers predict that the intervention will change patients’ knowledge? their attitudes? their motivation? The researchers’ view of how the intervention would “work” should drive the design of the intervention and the study.

Studies are not developed in a vacuum—there must be an underlying conceptualization of people’s behaviors and characteristics. In some studies, the underlying conceptualization is fuzzy or unstated, but in good research, a defensible conceptualization is made explicit. This chapter discusses theoretical and conceptual contexts for nursing research problems.

THEORIES, MODELS, AND FRAMEWORKS

Many terms are used in connection with conceptual contexts for research, such as theories, models, frameworks, schemes, and maps. These terms are interrelated but are used differently by different writers. We offer guidance in distinguishing these terms as we define them.

In nursing education, the term theory is used to refer to content covered in classrooms, as opposed to actual nursing practice. In both lay and scientific language, theory connotes an abstraction.

Theory is often defined as an abstract generalization that explains how phenomena are interrelated. As classically defined, theories consist of two or more concepts and a set of propositions that form a logically interrelated system, providing a mechanism for deducing hypotheses. To illustrate, consider reinforcement theory, which posits that behavior that is reinforced (i.e., rewarded) tends to be repeated and learned. The proposition lends itself to hypothesis generation. For example, we could deduce from the theory that hyperactive children who are rewarded when they engage in quiet play will exhibit fewer acting-out behaviors than unrewarded children. This prediction, as well as others based on reinforcement theory, could be tested in a study.

The term theory is also used less restrictively to refer to a broad characterization of a phenomenon. A descriptive theory accounts for and thoroughly describes a phenomenon. Descriptive theories are inductive, observation-based abstractions that describe or classify characteristics of individuals, groups, or situations by summarizing their commonalities. Such theories are important in qualitative studies.

Theories can help to make research findings interpretable. Theories may guide researchers’ understanding not only of the “what” of natural phenomena but also of the “why” of their occurrence. Theories can also help to stimulate research by providing direction and impetus.

Theories vary in their level of generality. Grand theories (or macrotheories) claim to explain large segments of human experience. In nursing, there are grand theories that offer explanations of the whole of nursing and that characterize the nature and mission of nursing practice, as distinct from other disciplines. An example of a nursing theory that has been described as a grand theory is Parse’s Humanbecoming Paradigm (Parse, 2014). Theories of relevance to researchers are often less abstract than grand theories. Middle-range theories attempt to explain such phenomena as stress, comfort, and health promotion. Middle-range theories, compared to grand theories, are more specific and more amenable to empirical testing.

Models

A conceptual model deals with abstractions (concepts) that are assembled because of their relevance to a common theme. Conceptual models provide a conceptual perspective on interrelated phenomena, but they are more loosely structured than theories and do not link concepts in a logical deductive system. A conceptual model broadly presents an understanding of a phenomenon and reflects the assumptions of the model’s designer. Conceptual models can serve as springboards for generating hypotheses.

Some writers use the term model to designate a method of representing phenomena with a minimal use of words, which can convey different meanings to different people. Two types of models used in research contexts are schematic models and statistical models. Statistical models, not discussed here, are equations that mathematically express relationships among a set of variables and that are tested statistically.

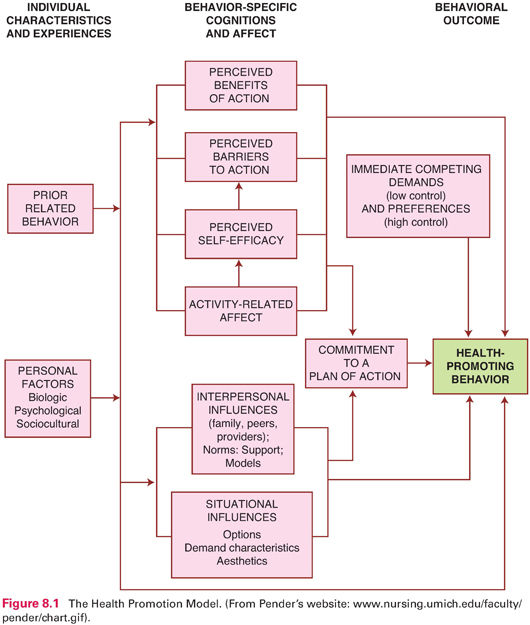

Schematic models (or conceptual maps) visually represent relationships among phenomena and are used in both quantitative and qualitative research. Concepts and linkages between them are depicted graphically through boxes, arrows, or other symbols. As an example of a schematic model, Figure 8.1 shows Pender’s Health Promotion Model, which is a model for explaining and predicting the health-promotion component of lifestyle (Pender et al., 2015). Schematic models are appealing as visual summaries of complex ideas.

Frameworks

A framework is the conceptual underpinning of a study. Not every study is based on a theory or model, but every study has a framework. In a study based on a theory, the framework is called the theoretical framework; in a study that has its roots in a conceptual model, the framework may be called the conceptual framework. However, the terms conceptual framework, conceptual model, and theoretical framework are often used interchangeably.

A study’s framework is often implicit (i.e., not formally acknowledged or described). Worldviews shape how concepts are defined, but researchers often fail to clarify the conceptual foundations of their concepts. Researchers who clarify conceptual definitions of key variables provide important information about the study’s framework.

Quantitative researchers are less likely to identify their frameworks than qualitative researchers. In qualitative research within a research tradition, the framework is part of that tradition. For example, ethnographers generally begin within a theory of culture. Grounded theory researchers incorporate sociological principles into their framework and approach. The questions that qualitative researchers ask often inherently reflect certain theoretical formulations.

In recent years, concept analysis has become an important enterprise among students and nurse scholars. Several methods have been proposed for undertaking a concept analysis and clarifying conceptual definitions (e.g., Walker & Avant, 2011). Efforts to analyze concepts of relevance to nursing should facilitate greater conceptual clarity among nurse researchers.

Example of developing a conceptual definition

Ramezani and colleagues (2014) used Walker and Avant’s (2011) eight-step concept analysis methods to conceptually define spiritual care in nursing. They searched and analyzed national and international databases and found 151 relevant articles and 7 books. They proposed the following definition: “The attributes of spiritual care are healing presence, therapeutic use of self, intuitive sense, exploration of the spiritual perspective, patient centredness, meaning-centred therapeutic intervention and creation of a spiritually nurturing environment” (p. 211).

The Nature of Theories and Conceptual Models

Theories, conceptual frameworks, and models are not discovered; they are created. Theory building depends not only on observable evidence but also on a theorist’s ingenuity in pulling evidence together and making sense of it. Because theories are not just “out there” waiting to be discovered, it follows that theories are tentative. A theory cannot be proved—a theory represents a theorist’s best efforts to describe and explain phenomena. Through research, theories evolve and are sometimes discarded. This may happen if new evidence undermines a previously accepted theory. Or, a new theory might integrate new observations with an existing theory to yield a more parsimonious explanation of a phenomenon.

Theory and research have a reciprocal relationship. Theories are built inductively from observations, and research is an excellent source for those observations. The theory, in turn, must be tested by subjecting deductions from it (hypotheses) to systematic inquiry. Thus, research plays a dual and continuing role in theory building and testing.

CONCEPTUAL MODELS AND THEORIES USED IN NURSING RESEARCH

Nurse researchers have used both nursing and nonnursing frameworks as conceptual contexts for their studies. This section briefly discusses several frameworks that have been found useful by nurse researchers.

Conceptual Models of Nursing

Several nurses have formulated conceptual models representing explanations of what the nursing discipline is and what the nursing process entails. As Fawcett and DeSanto-Madeya (2013) have noted, four concepts are central to models of nursing: human beings, environment, health, and nursing. The various conceptual models define these concepts differently, link them in diverse ways, and emphasize different relationships among them. Moreover, the models emphasize different processes as being central to nursing.

The conceptual models were not developed primarily as a base for nursing research. Indeed, most models have had more impact on nursing education and clinical practice than on research. Nevertheless, nurse researchers have turned to these conceptual frameworks for inspiration in formulating research questions and hypotheses.

| TIP The Supplement to Chapter 8 on |

Let us consider one conceptual model of nursing that has received research attention, Roy’s Adaptation Model. In this model, humans are viewed as biopsychosocial adaptive systems who cope with environmental change through the process of adaptation (Roy & Andrews, 2009). Within the human system, there are four subsystems: physiologic/physical, self-concept/group identity, role function, and interdependence. These subsystems constitute adaptive modes that provide mechanisms for coping with environmental stimuli and change. Health is viewed as both a state and a process of being, and becoming integrated and whole, that reflects the mutuality of persons and environment. The goal of nursing, according to this model, is to promote client adaptation. Nursing interventions usually take the form of increasing, decreasing, modifying, removing, or maintaining internal and external stimuli that affect adaptation. Roy’s Adaptation Model has been the basis for several middle-range theories and dozens of studies.

Research example using Roy’s Adaptation Model

Alvarado-García and Salazar Maya (2015) used Roy’s Adaptation Model as a basis for their in-depth study of how elderly adults adapt to chronic benign pain.

Middle-Range Theories Developed by Nurses

In addition to conceptual models that describe and characterize the nursing process, nurses have developed middle-range theories and models that focus on more specific phenomena of interest to nurses. Examples of middle-range theories that have been used in research include Beck’s(2012) Theory of Postpartum Depression; Kolcaba’s (2003) Comfort Theory, Pender and colleagues’ (2015) Health Promotion Model, and Mishel’s (1990) Uncertainty in Illness Theory. The latter two are briefly described here.

Nola Pender’s (2011) Health Promotion Model (HPM) focuses on explaining health-promoting behaviors, using a wellness orientation. According to the model (see Fig. 8.1), health promotion entails activities directed toward developing resources that maintain or enhance a person’s well-being. The model embodies a number of propositions that can be used in developing and testing interventions and understanding health behaviors. For example, one HPM proposition is that people engage in behaviors from which they anticipate deriving valued benefits, and another is that perceived competence (or self-efficacy) relating to a given behavior increases the likelihood of performing the behavior.

Example using the Health Promotion Model

Cole and Gaspar (2015) used the HPM as their framework for an evidence-based project designed to examine the disease management behaviors of patients with epilepsy and to guide the implementation of a self-management protocol for these patients.

Mishel’s Uncertainty in Illness Theory (Mishel, 1990) focuses on the concept of uncertainty—the inability of a person to determine the meaning of illness-related events. According to this theory, people develop subjective appraisals to assist them in interpreting the experience of illness and treatment. Uncertainty occurs when people are unable to recognize and categorize stimuli. Uncertainty results in the inability to obtain a clear conception of the situation, but a situation appraised as uncertain will mobilize individuals to use their resources to adapt to the situation. Mishel’s conceptualization of uncertainty and her Uncertainty in Illness Scale have been used in many nursing studies.

Example using Uncertainty in Illness Theory

Cypress (2016) used Mishel’s Uncertainty in Illness Theory as a foundation for exploring uncertainty among chronically ill patients in the intensive care unit.

Other Models Used by Nurse Researchers

Many concepts in which nurse researchers are interested are not unique to nursing, and so their studies are sometimes linked to frameworks that are not models from nursing. Several alternative models have gained prominence in the development of nursing interventions to promote health-enhancing behaviors and life choices. Four nonnursing theories have frequently been used in nursing studies: Bandura’s (2001) Social Cognitive Theory, Prochaska et al.’s (2002) Transtheoretical (Stages of Change) Model, the Health Belief Model (Becker, 1974), and the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 2005).

Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 2001), which is sometimes called self-efficacy theory, offers an explanation of human behavior using the concepts of self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and incentives. Self-efficacy concerns people’s belief in their own capacity to carry out particular behaviors (e.g., smoking cessation). Self-efficacy expectations determine the behaviors a person chooses to perform, their degree of perseverance, and the quality of the performance. For example, C. Lee and colleagues (2016) examined whether social cognitive theory–based factors, including self-efficacy, were determinants of physical activity maintenance in breast cancer survivors 6 months after a physical activity intervention.

| TIP Self-efficacy is a key construct in several models discussed in this chapter. Self-efficacy has repeatedly been found to affect people’s behaviors and to be amenable to change, and so self-efficacy enhancement is often a goal in interventions designed to change people’s health-related behavior. Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|