The Uninsured and Underinsured—On the Cusp of Health Reform

Catherine Hoffman

“Everybody should have some basic security when it comes to their health.”

—President Barack Obama on signing health care reform legislation, 2010

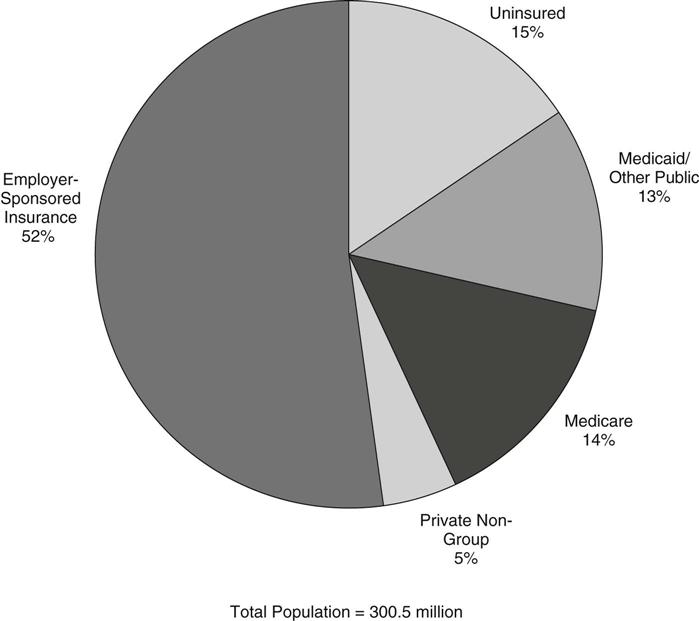

While the large majority of Americans have either private or public health insurance, gaps in our pluralistic health insurance system leave many millions—15% of the population—without health insurance coverage of any kind. Just over one half of the total population is covered privately as a benefit of their job, and a small share (5%) purchase private health insurance plans for themselves in the non-group market (Figure 21-1). The public arms of the system cover nearly all older adults through Medicare (14% of the population), with Medicaid and other public programs covering many, but not all, of those with low incomes (13% of the population) (Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured and the Urban Institute, 2009).

The problem of the uninsured has challenged the country for decades, but universal coverage had eluded policymakers. The combination of unabated growth in the number of uninsured, the unchecked growth in health care costs, questionable health care quality, and a deep economic recession created a consensus that the health care system was truly in crisis at this point and in need of major national health reform. Historic legislation that will markedly decrease the majority of the uninsured in the years ahead was passed and signed by the president on March 23, 2010. The policy work to implement the new laws is critically shaped by what is known about those who do not have health insurance today.

There were 46 million uninsured under the age of 65 in the United States in 2008. The problem affects people of all ages, colors, and income and educational levels—and bears real consequences. Not having insurance makes a substantial difference in people’s access to needed health care. In addition, millions of Americans who have health insurance do not have the financial security health insurance coverage should promise.

This chapter profiles the uninsured, who they are, why they do not have health coverage, and the difference not having health insurance makes in their lives. It also provides an overview of our health insurance system, describing the holes in the system, why they exist, and the funding of “charity care.” The chapter concludes with key elements of the current national health reform legislation that attempt to address the many barriers to access to health insurance in the U.S..

Holes in the Health Insurance System

Gaps in health insurance coverage, be they short or last for years, are primarily a problem only among the nonelderly because nearly all who are 65 years and older are covered by Medicare. More than one half of the nonelderly receive health coverage as an employer benefit. Those who do not have access to or cannot afford employer-sponsored or private non-group insurance go without health coverage unless they qualify for Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), or other subsidized insurance programs.

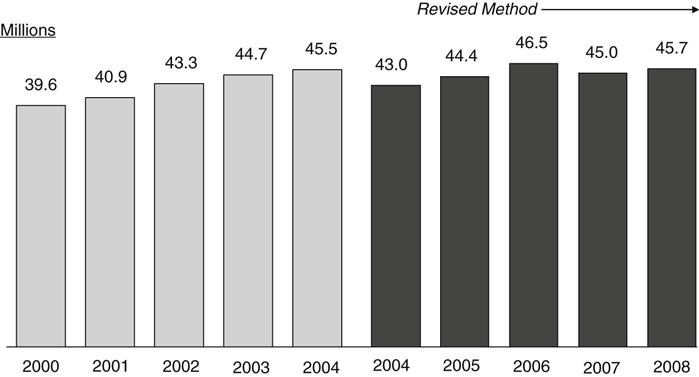

The number of nonelderly uninsured has been growing steadily every year since 2000 by about 1 to 2 million, with the exception of a dip in 2007 when the otherwise steady decline in employer-sponsored coverage leveled off briefly (Figure 21-2). By 2008, however, the number of nonelderly uninsured Americans rose again and is expected to continue to climb as a consequence of the country’s recession and persistently high unemployment rate.

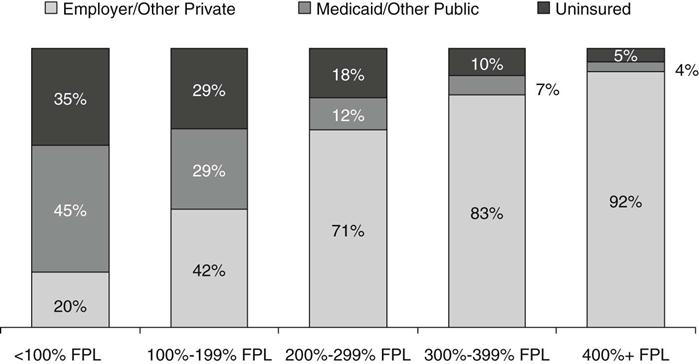

The holes in the health insurance system for the nonelderly left 1 in 6 (17%) of the nonelderly uninsured in 2008. And because being insured is largely a condition of being able to afford insurance, the chances of being uninsured are considerably higher for those who have low incomes (Figure 21-3). The nonelderly poor are seven times as likely to be uninsured compared to those with high family incomes (35% uninsured vs. 5% among those with incomes of four times the federal poverty level [FPL] and higher) (Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured and the Urban Institute, 2009).

Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance

About 60% of people in the U.S. under the age of 65 obtain their health insurance through an employer, making it the most common form of health coverage. However, having a job does not guarantee a person will have access to employer-sponsored coverage; in fact, about 37 million of the uninsured are in families that have at least one working member (Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured and the Urban Institute, 2009). The share of the nonelderly population with employer-sponsored coverage has been declining since 2000—even during periods when the economy was stronger and growth in health insurance premiums was slowing—and has been exacerbated by two recessions.

Businesses are not required to offer job-based coverage to their workers, although 60% of businesses did in 2009. Almost all large firms with more than 200 workers offer a health insurance benefit. Smaller firms and those with more low-wage workers are much less likely to offer health benefits. Across industries, uninsured rates for workers range from 35% in agriculture to just 5% in public administration. But even in industries where uninsured rates are lower, the gap in health coverage between blue-collar and white-collar workers is often two-fold or greater. More than 80% of uninsured workers are in blue-collar jobs. More than half of employees in poor families are not offered coverage either through their own employer or their spouse’s employer, compared to just 4% of employees at or above 400% of the FPL (Clemans-Cope & Garrett, 2006).

Even when businesses offer health benefits, not all employees are eligible because they work part-time or have been recently hired. Among firms that offered health insurance benefits in 2009, an average of 79% of their workers were eligible for them (Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research & Educational Trust, 2009). Other workers may not participate in their company’s health benefits because they cannot afford the employee share of the premium.

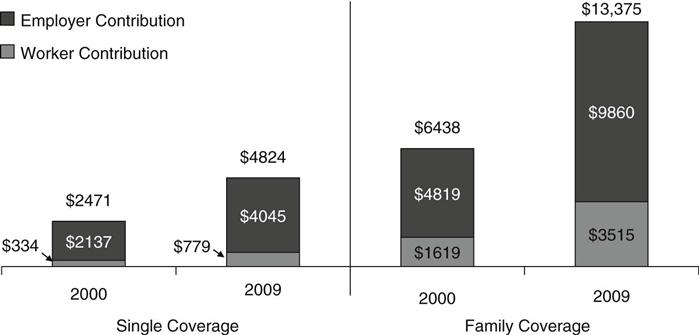

The high cost of health insurance is the most common reason employers report for not offering coverage and why individuals do not buy it for themselves. Health insurance premiums have been escalating, outpacing the growth in wages and general inflation by three-fold in the past decade. In 2009, annual employer-sponsored group premiums averaged $4824 for individual coverage and $13,375 for family coverage. Total family premiums and the employee’s share of the premium have doubled since 2000 (Figure 21-4) (Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research & Educational Trust, 2009). Despite the high cost, the majority of employees participate in their employer’s health plan when they are offered coverage, even among those with very low incomes (Clemans-Cope & Garrett, 2006).

Medicaid’s Role for the Nonelderly

Medicaid is the nation’s major public health insurance program for low-income Americans, a partnership between each state and the federal government to provide a health insurance safety net. Unlike Medicare, which covers nearly all older adults, Medicaid is an entitlement for only certain categories of the nonelderly. Medicaid limits its reach to four main groups: children, their parents, pregnant women, and people with disabilities—with the program playing its broadest role among children.

Federal law requires states to cover school-age children up to 100% of the FPL and 133% of the FPL for preschool children. The Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), created in 1997 to expand coverage to more low-income children, complements Medicaid by covering low-income children with family incomes higher than Medicaid eligibility levels. Through the combination of Medicaid and CHIP, most states cover children up to or above 200% of the FPL (see Chapter 18). Together these programs cover more than one half of all low-income children and have played a critical role in improving access to care for children.

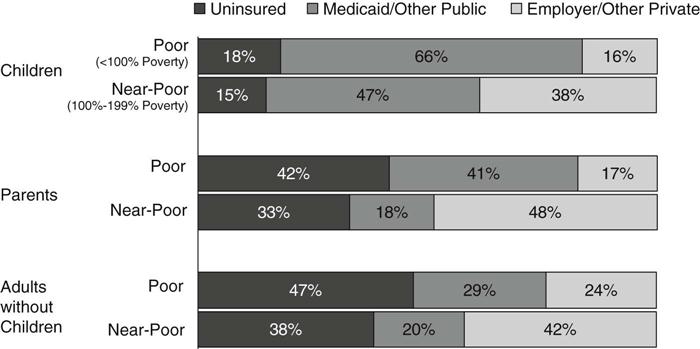

In contrast to coverage for children, the role of Medicaid for nonelderly adults is more limited. While all poor children are eligible for Medicaid, many of their parents are not. States are only required to cover parents with incomes below their state’s 1996 welfare eligibility levels, which is often below 50% of the FPL. In addition, although Medicaid covers some low-income individuals with disabilities, most adults without dependent children—regardless of how poor—are ineligible for Medicaid. As a result, over 40% of poor parents and adults without children are uninsured (Figure 21-5) (Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured and the Urban Institute, 2009).

Over the past decade, growth in Medicaid enrollment has helped buffer the loss of employer-sponsored coverage, containing the growth in the number of uninsured. As the health insurance safety net for the nonelderly, enrollment in Medicaid always increases during economic downturns when people lose their jobs. However, at the same time, recessions also decrease state revenues and they are less able to meet the increased need.

In recent years, states have used their Medicaid and CHIP programs as a foundation for broader health care coverage expansions, taking advantage of the existing delivery and administrative systems as well as federal matching funds to help finance the expansions. In addition, several states have obtained waivers of federal requirements to expand coverage to childless adults through their Medicaid programs (Artiga & Schwartz, 2009). These programs, along with coverage expansions for low-income children and families, have been a cornerstone of state strategies to address the problem of the uninsured.

Profile of the Uninsured

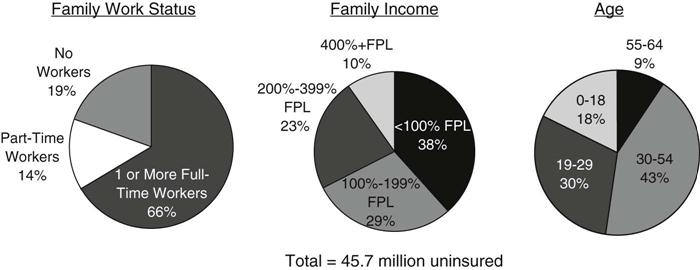

In 2008, 45.7 million people in the U.S. under age 65 did not have health insurance (Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured and the Urban Institute, 2009). Most of them were adults, and were from working families earning low incomes. In fact, more than 8 in 10 of the uninsured are members of working families—about two thirds are from families with one or more full-time workers, and 14% are from families with part-time workers. Only 19% of the uninsured are from families that have no connection to the workforce (Figure 21-6). Even at lower income levels, the majority of the uninsured are in working families. Among the uninsured with incomes below the FPL ($22,025 for a family of four in 2008), 55% have at least one worker in the family (Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured and the Urban Institute, 2009).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree