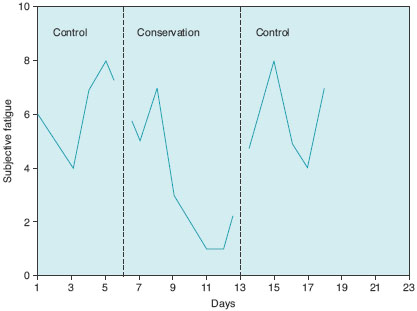

As may be seen, in this example, the increase in fatigue following withdrawal of intervention during the second A phase is taken as evidence of the effectiveness of the intervention. However, for some interventions (e.g. education provision) we would not expect to see a return to baseline, because once something is known, it is not possible to artificially render it unknown again. Accordingly, ABA designs should be assessed in terms of their appropriateness for the treatment being offered. In general, if the treatment requires ongoing input, an ABA design is likely to be appropriate, and will increase our confidence that changes in the dependent variable (fatigue) are a consequence of manipulation of the independent variable (conservation versus no intervention).

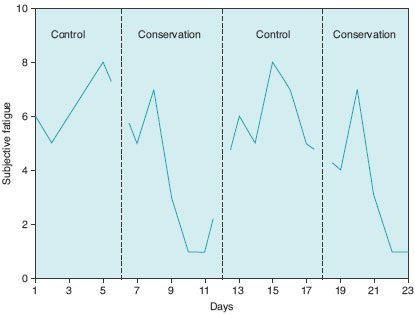

The ABAB design

There is also an ethical dilemma with the ABA design, because the patient is left in a situation where, at the end of the study, treatment has been withdrawn. This situation is readily remedied by the reintroduction of the treatment phase, as in the ABAB design (Figure 16.3).

An additional advantage of this design is that the researcher has further comparison points A1 versus B1, A2 versus B2, A1 versus B2, A1 versus A2. Consistent differences between the A and B points, plus similarity between A1 and A2 would greatly increase our confidence that the independent variable was responsible for changes in the dependent variable.

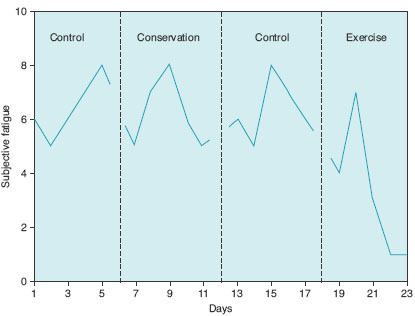

The ABAC design

In clinical practice, the ABAB approach may be expanded and allow us to introduce a series of different interventions sequentially, each interspersed with a return to baseline. In Figure 16.4, conservation has proved ineffective in reducing fatigue, and so, following a second baseline control (A) phase, a different treatment (exercise) is introduced forming a C phase in the experiment. These are sometimes referred to as ABAC designs. Theoretically, further baseline phases and treatment phases could be added indefinitely, with each treatment phase being designated a different letter – ABACADAEA, and so on.

Notice that this approach reflects the clinical situation where the HCP and client together explore a series of different, potentially effective approaches to the client’s difficulties. One important difference is that in SCEDs there is always a return to baseline, permitting better control of the independent variable. In clinical practice, what most clinicians actually do is omit the baselines (ABCDE). Although this seems to save patient and HCP time, it is not only a weaker research design, because there is only one baseline to measure change against, but potentially wasteful of time, because problem assessment will be poorer without good baseline measurement, and the introduction of different treatments may, in consequence, be inappropriate. The ABAC design is extended to include further baseline and a D component featuring, for example, CBT, after both conservation and exercise have been ineffective in altering subjective fatigue (ABACAD).

Where it is acceptable to the patient, we can introduce an element of randomisation, varying both the order in which treatments are introduced and the length of each treatment. This may greatly strengthen our confidence in inferences to be drawn from difference between the treatment and control phases, both by reducing order effects (see Chapter 15) and increasing the range of possible appropriate statistical treatments (Kazdin, 1982). Randomisation also decreases the likelihood that client and therapist are merely capitalising on their observation of naturally occurring fluctuations in behaviour in deciding when to start another phase.

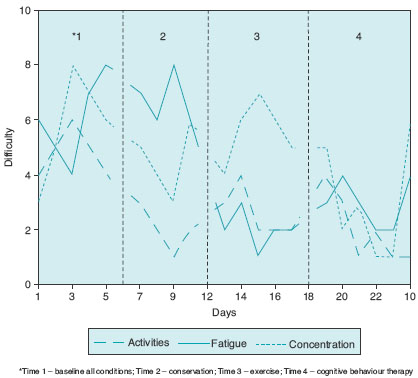

Multiple baseline designs

In AB designs and their variants, we infer cause and effect relationships on the basis of differences between the baseline and treatment phases. The grounds for such inference in multiple baseline designs are slightly different. With such designs, we investigate the effect of interventions on a range of different problems simultaneously, and there is usually no withdrawal of treatment once intervention has begun for each problem. In Figure 16.5, the HCP has used conservation in an effort to increase the range of a patient’s activity, exercise to improve their subjective fatigue and CBT to improve their concentration. Although the three approaches have been introduced sequentially, they each address a different problem, all of which have been monitored from the start. Thus, for each problem, there is a different length of monitoring, overlapping with other treatments. In multiple baseline design, the main rationale for inferring cause and effect comes from the comparison of treated and untreated problems at the same time point. We infer that treatment is effective by observing differences between patient ratings of the treated and untreated problems. Another approach would be to use the same treatment approach for each problem, but to specifically target each problem in turn, whilst maintaining baseline measurement for the untreated ones.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree