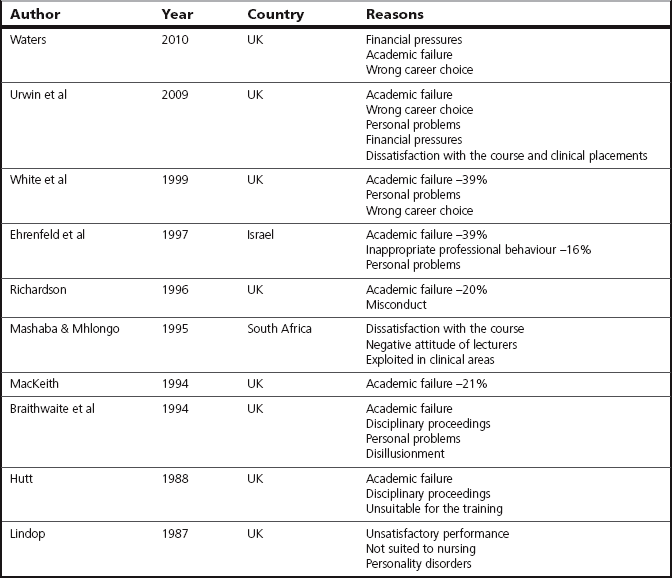

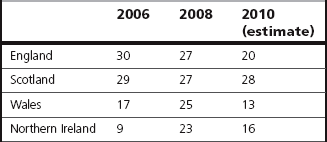

Chapter 1 In this chapter, I shall consider why we assess at all in the health care professions. These supposedly educational and professional purposes of assessment will be explored in conjunction with their potential for causing short- and long-term negative consequences for the students on whom we have passed ‘judgement’. Mindful of the context of assessment being discussed in this book, this chapter will also take a look at the complexities of clinical assessment. The phrase ‘complexities of clinical assessment’ is used with intent: it is used on the assumption that, for many readers of this book, the nature of learning and assessing in the clinical setting will be close to their hearts as a direct result of significant and meaningful personal experiences of having been a learner and been assessed, and having worked and been an assessor, in that setting. We all are keenly aware of the importance of assessment and the influence it has on our lives. As Rowntree (1987:xii), in perhaps one of his philosophical moments, points out: And don’t Rowntree’s sentiments strike a strong chord! Consciously or subconsciously, we are assessing most of the time, be it at work, at home or even when out walking in the countryside. And as Broadfoot (1996:3) noted, ‘assessment is a central feature of social life’. Passing judgement on people, on events, on ideas, on things and on values is part of the process of making sense of the world around us and where we stand in any given situation. Sometimes we judge to reassure ourselves – I am glad I am not as selfish as she is – (and we might be rather lacking in self-awareness)! We are all assessors; even very young children are capable of making assessments – ask a young child whether she or he likes her/his new school and, of course, the response will be either a ‘yes’ or a ‘no’. The ability to respond implies that the child has activated the mental processes involving a mental review of perhaps the teachers, the other children, the events and the activities that she or he likes or dislikes and has applied more or less conscious criteria to what would constitute, for instance, a like or dislike of the teacher. In social settings and during social interactions we may not be asked to justify our judgements and, indeed, may be most taken aback and even feel embarrassed if asked to do so. However, in educational and professional settings, such justification is frequently required as the process of assessment is overt, formalized and controlled. The criteria we use are often subject to scrutiny and we are required to make our assessment decisions on the basis of available evidence. The scenario of ‘bad’ days as painted appears to be an ongoing one and remains a problem. In 1989, Watts reported that, after an initial period of supervision, student nurses on a first clinical placement were left to practise independently. If they sought supervision and feedback, it was given. Students who were unaware of incorrect practice would continue to practise incorrectly without seeking help. The assumption made was that, if no help was required, ‘all was well’. Even assessment was carried out by inference; trained staff would assume safe and competent practice from students’ expressions of confidence. Assessors of pre-registration nursing and midwifery students in the studies by Bedford et al (1993) and Phillips et al (2000) reported experiencing role strain and role conflict, and teaching and assessing students became an additional burden. Later studies by Henderson et al (2006) and Hurley & Snowden (2008) found that assessors could not attend to students’ needs fully when demands of patient care overrode teaching duties. Consequently, students’ learning and assessing needs were marginalized and placed in opposition to client care needs, with students having to fend for themselves. Learning and assessment in clinical practice seem to be rather ‘hit and miss affairs’. Why then do we bother to assess students in clinical practice, and during their educational programme in general? What are the purposes of assessment? It is perhaps appropriate to explore these at this point. You may wish to try Activity 1.1 before you proceed. The nursing, midwifery and medical professions have required their ‘trainees’ to be examined since the 19th century. The medical profession was the first profession to institute qualifying examinations in order to determine competence (Broadfoot 1979). This commenced in 1815. In 1872, the London Obstetrical Society took the initiative to set up its own examination board to examine women between the ages of 21 and 30 who wanted to be certified as a ‘skilled Midwife, competent to attend natural labours’ (Donnison 1988:85). This examination comprised a written and oral examination (Sweet & Tiran 1997). In the case of nurses, the first examination was held with the establishment of a School of Nursing at the London Hospital in 1880 (Seymer 1949). Students had to sit an examination consisting of a paper, a viva voce and a practical test in the wards, at the end of their first and second years of training (Bendall & Raybould 1969). Certificates were awarded on successful completion of the 2-year course. To accept the necessity for assessment unthinkingly denies a complex debate concerning the purposes of assessments. The effects of the assessment on the learner as an individual, and its impact on the curriculum, teaching and learning, may also be overlooked. Rowntree (1987:xii) pointed out that even though educational assessment is confined to a fairly small proportion of our lifespan it can have a disproportionate negative effect on the rest of our lives. The ‘evidence’ from these assessments can make or break us in life as it can tell other people (and ourselves) what to think and feel about us – life’s doors may either be open or shut for us as a result of being so judged. Critically reviewing ‘why’ we assess may make us consider more carefully whether our assessments are reasonable and just. As professionals, we like to think that we know why we are doing what we are doing most, if not all, of the time. However, Foucault (1982:182) has this to say: ‘People know what they do; they frequently know why they do what they do; but what they don’t know is what what they do does’. Klug (1975) acknowledged that one of the many difficulties of discussing the theme of assessment lies in the tangle of issues involved: even its explicit and acknowledged functions are multifarious and conflicting. In an earlier publication Klug (Klug 1974 in Rowntree 1987) gathered 32 reasons for formal assessment. Here, I shall concentrate on what I see are the four main reasons commonly advanced for assessment in professional health care education. In the UK, the typical academic qualifications (with some variations between the requirements of different Higher Education Institutions) required for entry to pre-registration nursing and midwifery programmes include three GCE ‘A’ levels, grade C or above; or five GCSE/GCE ‘O’ levels, grade C or above; or the General National Vocational Qualification (GNVQ) Advanced level or an Access course for Higher Education. Candidates have to prove that their ability to contribute to the profession is greater than that of others. One of the assumptions implicit in this selection procedure is that only those who are deemed capable of successfully completing the training are funded for the education programme. Disappointingly, the correlation between fulfilment of selection criteria and successful completion of training is low. Levels of discontinuation from pre-registration nursing and midwifery courses are a source of concern. In earlier years, statistics published by the English National Board (ENB 2002) for the period 1996–2001 show that the non-completion rate of all pre-registration student nurses and student midwives was between 15 and 18%. Later statistics show that the situation has worsened. Statistics from the Higher Education Statistics Agency in the UK show that, for the period 2002/03 to 2003/04, just 68% of nursing students stayed the course (Waters 2006). In 2006 in the UK, the Department of Health (2006) declared that nursing student attrition rates of more than 15% are unacceptable. In the intervening period to 2010, despite various policy initiatives, the attrition rate has risen to almost double that target in England. It hit 30 per cent in Scotland (Scott 2010). Scott went on to say that the admissions process cannot be working effectively if applicants accepted on courses discover after a matter of weeks that nursing is not for them. Table 1.1 show the attrition rates for the UK for the years 2006, 2008 and 2010 (Waters 2010). The statistics clearly show a high ‘casualty’ rate. Table 1.1 Attrition rates for pre-registration nursing students in the UK: 2006, 2008, 2010 (From Waters A 2010 The question for universities: how can they win the war on attrition? Nursing Standard 24(24):12–15.) Internationally, the scale of the problem is difficult to quantify from the literature, partly because of differences in definition and partly because of incomplete and non-comparable data. Ehrenfeld et al (1997) gave a figure of 23.5% over a 5-year period for their own institution in Israel. Mashaba & Mhlongo (1995) from South Africa reported an attrition rate of 31.2% over a 5-year period for the institution under investigation. This compared with 64% over the same 5-year period for eight institutions (including the study institution) offering the same course. Reasons for discontinuation are many and varied. There is no intention here to explore these but to refer only to those that, by our stringent selection criteria, we seek to prevent from occurring. These reasons are listed in Table 1.2 for ease of reference. Readers are directed to the work of Urwin et al (2009) where a comprehensive critical review and analysis of 123 records to identify factors contributing to student nurse attrition found that individual student factors, institutional issues and broader political, professional and societal issues were the key reasons for the attrition. The non-completion rate is similar in occupational therapy (Ilott 1993, in Ilott & Murphy 1999). Ilott reports that, for the period 1987–1990, the collective rate for three intakes of students was 14.6%. The most common reason was academic failure, which was defined as an inability to cope with the course, and/or to learn by failure on internal or professional assessment. Salvatori (2001) reviewed 83 articles from the disciplines of medicine, nursing, midwifery, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, respiratory care and medical imaging for the reliability and validity of both cognitive and non-cognitive measures used to select students to health care programmes. The conclusion drawn was that an admissions process that provides a ‘thorough, fair, reliable, valid and cost-effective assessment of applicants remains an elusive goal for health profession education programs’. Our selection procedure invests us with the power to reject those whom we perceive do not fulfil our selection criteria. Prior academic achievement may be seen as one criterion that is an objective measure for selection for entry to health care education, and ultimately the health care profession. Even the relevance and usefulness of this perceived ‘objective measure’ has serious shortcomings. As can be seen in Table 1.2, academic failure is cited as a key reason for discontinuation of nurse education in all studies. This certainly casts great doubt over the assumption that those who perform best in current examinations are those who would become most capable as a result of further educational investment. Perhaps such factors as maturity, personality and motivation are also important in determining success in nursing and midwifery education. Readers are directed to discussions of these latter issues in the papers by Deary et al (2003) and Glossop (2001). Thomas Love Peacock (1860 in MacLeod 1982:7) railed against the preponderance of examinations that would ‘infallibly have excluded Marlborough from the Army and Nelson from the Navy’! Of the candidates we reject, we will never know how many would have become the sensitive and caring nurse or midwife or physiotherapist or doctor – their potential may never be realized. The academic high-flyer may not be the better practitioner if she/he does not possess qualities such as compassion and empathy. Statutory regulation of health professionals is well established. The primary purpose of statutory regulation is to protect the public. In the UK, medical practitioners have been subject to state registration since 1858 with the passing of the Medical Act; midwives since 1902 with the Midwives Act, and nurses since 1919 with the Nurses Registration Act. Regulation of the professions supplementary to medicine (chiropodists and podiatrists, dieticians, medical laboratory scientific officers, occupational therapists, orthoptists, physiotherapists and radiographers, both diagnostic and therapeutic) followed in 1960 with the passing of the Professions Supplementary Act 1960. This was extended in 1997 to include prosthetists and orthotists and arts therapists (Department of Health 2000). With the passing of The Health Professions Order 2001, the Health Professions Council was created and currently regulates 16 professions: arts therapists, biomedical scientists, chiropodists/podiatrists, clinical scientists, dietitians, hearing aid dispensers, occupational therapists, operating department practitioners, orthoptists, paramedics, physiotherapists, practitioner psychologists, prosthetists/orthotists, radiographers, social workers in England and speech and language therapists (Health and Care Professions Council 2012). With statutory regulation, Parliament grants a profession the right to self-regulation. This means that a profession is given the right to maintain professional discipline, standards of conduct and entry into the profession. Standards of professional behaviour and for employment have to be observed by those who are registered with a statutory body. These standards are upheld through the key functions of education, registration and discipline. The standards of conduct, performance and ethics of the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC, 2008a) and the Health and Care Professions Council (2008) are concerned with maintaining a standard of practice such that high-quality care is provided to the recipients of health care at all times. As discussed earlier, the issue of a ‘licence’ to practise by a professional statutory body offers some measure of public protection. The public has a fundamental right to expect competence from the qualified professional in health care, and protection against unsafe, unscrupulous or sick practice. The mechanism of statutory registration is designed to ensure that those legally entitled to call themselves ‘midwife’, ‘nurse’, ‘physiotherapist’, ‘occupational therapist’, ‘operating department practitioner’ and so on possess the outcomes and competencies described in statute. For nurses and midwives and those professions regulated by the HCPC, the rules and standards of proficiency for pre-registration programmes leading to registration on the NMC and HCPC registers are currently set out in the Nursing and Midwifery Council (Education, Registration and Registration Appeals) rules 2004 (NMC, 2004a) and in The Health Professions Order 2001 (Education and Training rules). More recently, the NMC (2009, 2010a) mandated that pre-registration nursing and midwifery programmes must be designed to prepare the student to provide the nursing and midwifery care that patients/clients require, safely and competently, and to be able to assume the responsibilities and accountabilities necessary for public protection. The HCPC (2009a) mandated that all pre-registration programmes must prepare the student to have the knowledge, skills and experience to practise safely and effectively in a way that meets the standards of the HCPC, and no danger is posed to the public or the self. The educational and professional outcome of pre-registration education is a competent practitioner who is fit to practise. Both the NMC (2008a) and the HCPC (2008) make it clear that fitness to practise is a registrant’s suitability to be on the register without restrictions. This means that, prior to being admitted to the professional registers, there must be evidence that the student is able to uphold the standards of conduct, performance and ethics expected of registrants set out in the respective professional’s codes of practice. It is incumbent upon practitioners to facilitate the learning and development of students so that evidence of fitness to practise is generated and provided through assessment processes. This evidence needs to be valid and reliable to provide the objective data upon which assessment decisions of fitness to practise can then be made. We may need to remind ourselves that the NMC and HCPC are reliant on this assessment decision for conferring professional registration upon the nurse or midwife, or orthoptist, radiographer or paramedic and so on. Take a few moments to consider Activity 1.2. If it is accepted that one of the purposes of assessment is to prepare practitioners who are fit for practice, the answer to the question posed in Activity 1.2 is that this purpose is not fully realized (Cleland et al 2008, Luhanga et al 2008, Duffy 2004, Bradshaw 2000, Glen & Clark 1999, Runciman et al 1998). The following point was made by the UKCC Education Commission on nursing and midwifery education (UKCC 1999a): Similar concerns were expressed by the NMC (2005a). Reasons for this are wide ranging (Cleland et al 2008, Luhanga et al 2008, Glen & Clark 1999). Among the most notable is the confusion in the terminology of ‘competence’ – thereby contributing to difficulties experienced by assessors when required to assess competent practice (Watson et al 2002, Bradshaw 2000, Fraser et al 1997, Bedford et al 1993). Other studies reported assessors’ lack of skills, knowledge and confidence to assess and report underperformance in order to take the necessary remedial action (Cleland et al 2008, Luhanga et al 2008, Dudek et al 2005). Closely related to the purpose of assessing for entry into the profession is this second purpose. In industry such as manufacturing, quality control of production enables those items below the required standard to be rejected. With the purpose of assessment as a form of quality control for the health care professions, assessors should be able to identify those students who have not achieved the educational standards, and therefore, make a ‘fail’ decision so that the names of those who are not ‘competent’ are not entered into the professional register. Among other roles, assessors need to be the ‘gatekeepers’ of their profession to achieve the quality control function of assessment. A crucial question to ask is ‘How adequately, or how well, is this “gatekeeping” role being performed?’ Again, the sobering answer is that this purpose of assessment is not fully realized as the ‘gatekeeping’ is inadequate. There is a ‘failure to fail’ students with grave consequences for the public that we serve: their health and well-being are supposed to be protected by the registrants on the professional register. In fairly recent times, the case of Beverley Allitt (Clothier et al 1994) is perhaps a tragic example of how the nursing profession has let the public down. Beverley Allitt was an enrolled nurse who was convicted of murdering four children and harming nine others, some of who have been left severely brain damaged. In 1990 when she was still a student she took 94 days of sick leave, which delayed her qualification. As a student, she had a history of inflicting injuries on herself and others. How did she pass her training, or, why was she not failed? Allitt’s fitness to practise was impaired but she achieved professional registration. The points of fitness to practise and fitness for practice will be developed in Chapter 3. This complex problem of ‘failure to fail’ is not new and appears to be a continuing challenge for assessors of students on pre-registration professional courses. In the health care professions, the issue of ‘failure to fail’ is reported in literature relating to assessment in the fields of social work (Brandon & Davis 1979), medicine (Cleland et al 2008, Green 1991), nursing and midwifery (Luhanga et al 2008, Duffy 2004, Fraser et al 1997, Bedford et al 1993, Lankshear 1990) and occupational therapy (Ilott & Murphy 1999). References are made to assessors giving students the benefit of the doubt in marginal situations instead of awarding a fail when it was clearly warranted. To determine whether pre-registration students have achieved the threshold standards or competence, assessors must make the crucial ‘pass/fail’ assessment decision. Higher-education institutions have to make decisions of impairment of fitness to practise. These vital decisions protect the public from unsafe, incompetent or unscrupulous practitioners. This is crucial for quality control and, as one of the purposes of assessment, it also serves to safeguard the standards of the profession. The complex situation of ‘failure to fail’ will be explored further in Chapter 7. Professional conduct: The quality control purpose of assessment for qualified professionals serves to maintain the standards of the profession through the regulation of the education, training and conduct of its registrants. In the case of nurses and midwives and those professions regulated by the HCPC, both the NMC and HCPC maintain a register of practitioners who have met the standards for entry to the professions. This is central to the Councils’ role in protecting the public. Being on the NMC and HCPC registers demonstrates to the public that practitioners have accepted the responsibilities and accountability that go along with registration, and that they will abide by the professional standards set by the NMC and the HCPC. This is done through professional self-regulation. Professional self-regulation means that, in exercising professional accountability, professional knowledge, judgement and skill are used to interpret and apply professional standards in practice. Although the NMC and the HCPC administer the system of professional self-regulation, it is through its practitioners who are accountable for their own practice that professional standards are maintained in the workplace. The Standards of conduct, performance and ethics of the NMC and the HCPC (NMC 2008, HCPC 2009a) are the basis of the regulatory framework. Practitioners are required to monitor and maintain not only their own professional standards but also those of their colleagues. In exercising individual professional responsibility and accountability, the Standards require practitioners to report to an appropriate person or authority any circumstances that may put patients and clients at risk. The position of the NMC and the HCPC on this is explicit. Two of the clauses in the NMC standards above state that: The HCPC standards are equally explicit in stating that: In 2004, the NMC published guidelines for employers and managers for reporting unfitness to practise (NMC 2004b) and reporting lack of competence (2004c); later guidelines (2010b) gave information on the four broad areas of misconduct, lack of competence, character issues and poor health when allegations are investigated. Likewise, guidelines published by the HCPC in 2007 gave similar guidance for reporting allegations against its practitioners. The guidance provided by these publications reinforces the quality control purpose of assessment of practitioners, which in turn supports the primary mandate of the NMC and the HCPC: to safeguard the health and well-being of the general public. Between 2010 and 2011, the NMC received 4211 allegations (0.7% of registrants, compared with 2988 the previous year) against its registrants for their fitness to practise (NMC 2011), and the HCPC received 759 allegations (0.35% of registrants, compared with 772 the previous year) (HCPC 2011). The allegations of fitness to practise against these practitioners indicate that the quality control purpose of assessment of practitioners is necessary.

The purposes and nature of assessment and clinical assessment

Introduction

The nature of assessment

The purposes of assessment

Assessment for entry into the profession

Students in training

Assessment as a form of quality control

Qualified professionals

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The purposes and nature of assessment and clinical assessment

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access