CHAPTER 18 The professionalisation of paramedics: the development of pre-hospital care

When you finish this chapter you should be able to:

Introduction

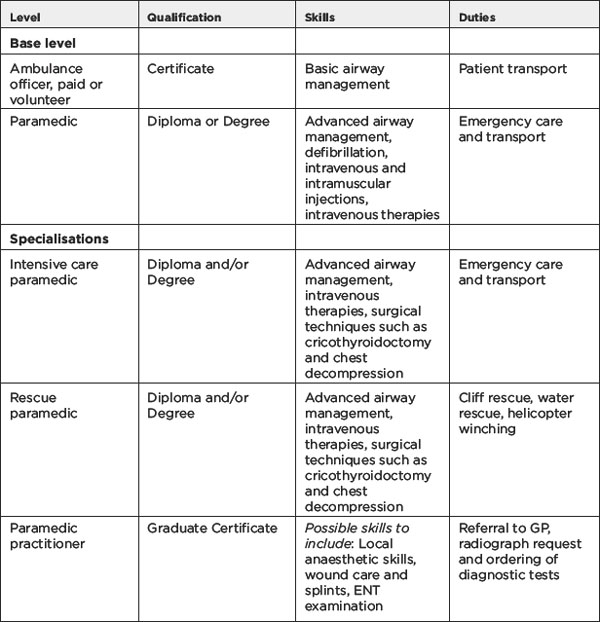

The role and the work of the paramedic in Australia is defined through state and territory legislation — Ambulance Service Act (Tas) 1982; Ambulance Services Act (Vic) 1986; Health Services Act (NSW) 1997; Ambulance Service Act (Qld) 1991; Ambulance Services Act (SA) 1992; Emergencies Act (ACT) 2004). While the term paramedic has been adopted in recent time, paramedics were formally known as ambulance officers. Across Australia paramedics work in a voluntary capacity or are employed by ambulance services to treat and transport patients to and from hospital and are able to instigate various forms of medical treatment. The nature and type of this medical treatment is dependent on their qualifications and training. Table 18.1 outlines the various grades of paramedics in Australia with their associated qualifications and duties.

Historical overview of the evolution of pre-hospital care

Several hundred years later, in 960 Avicenna, a Muslim philosopher stated: ‘…When necessary, a cannula of gold or silver is advanced down the throat to support inspiration’ (Avicenna 1970). In 1767 the Dutch Humane Society described methods of resuscitation to include: ‘…keep the victim warm, give mouth-to-mouth ventilation, and perform insufflation of smoke of burning tobacco into the rectum’ (Varon & Fromm 1993). In 1914 Dr Crile described the use of adrenaline in resuscitation (Crile 1921) and in 1920 Hooker and Kouwenhoven were able to treat the life-threatening cardiac event of ventricular fibrillation with the application of electrical current to the heart (Hooker, Kouwenhoven & Langworthy 1933).

In some states and territories, such as South Australia, Western Australia and the Northern Territory, the Order of St John was instrumental in the early development and organisation of the first ambulance services. In other states the government assumed early control over the operations relegating the Order of St John solely to first aid training (Wilde 1999). St John remains the primary ambulance service in Western Australia and the Northern Territory.

The relationship between paramedic, nursing and medicine

Unlike a number of other health professional groups, paramedics are not currently required to be registered with a regulating body, nor do they require a licence or registration to practise. However, they do require an authority to practise. This is usually achieved at the end of a formal internship which varies in duration from state to state and territory, and according to the type of education; for example, VET or university-based. In response to the 2005 Australian Productivity Commission report into Australia’s Health Workforce, the Coalition of Australian Governments (COAG) has recommended that health professionals who are required to be registered do so under a single national body. Such a move would cater for health professionals such as paramedics to move into special needs areas or to extend their scope of practice through role substitution (COAG 2007). The Council of Ambulance Authorities is currently exploring the COAG recommendations.

The relationship between paramedic, nursing and medicine offers unique opportunities for collaboration for 21st century health care and we outline some of these developments below. Many nurses train as paramedics and increasingly universities are offering combined nursing/paramedic degree programs. Interestingly, many paramedic academics see the development of a body of professional knowledge and research as closely aligned with medicine. Unlike nursing they are not seeking professionalisation through a strong separation from medicine. This may well be a result of the youthfulness of the profession, the close control still exercised by medicine over paramedic practice, or simply a pragmatic response to power. There are parallels between paramedic, nursing (see Chapter 16) and midwifery (Chapter 17) in their relationship to medicine.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Pause for reflection

Pause for reflection