CHAPTER 5 The private sector and health insurance

When you finish this chapter you should be able to:

Introduction

The Australian health care system relies on multiple sources to provide funding. As introduced in Chapter 1, ultimately these all rely on money paid by individuals, who contribute these funds through the tax system, by paying medical practitioners and other health care professionals directly, or by contributing to private heath insurance schemes. Additionally, funding for the health care system also comes from special purpose funds such as state-based motor vehicle accident or workplace injury compensation schemes, or through payments made for medical and hospital expenses of former defence force personnel (usually known as veterans).

Health funding systems which are administered by governments and use some form of tax to raise funds from citizens are known as ‘public schemes’. Systems that rely on individuals (or sometimes companies) paying a premium or contribution to obtain insurance cover for health care expenses are known as ‘private schemes’. There is much debate about which system is likely to produce the best health outcomes for particular populations, but fundamentally all such schemes are ‘pipelines’ for the allocation of money (Richardson 1995). Many of the arguments in this area are about relative efficiency and equity in terms of achieving good health outcomes, and this is certainly the case in Australia.

Health insurance in Australia

How does health insurance work; where does the money go?

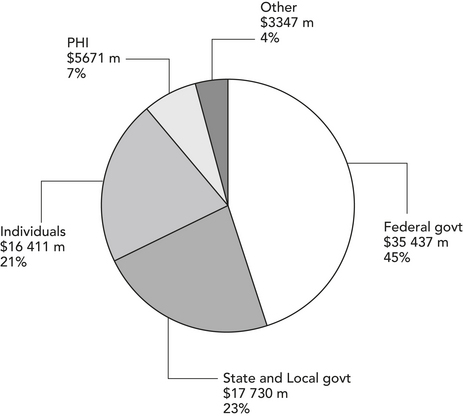

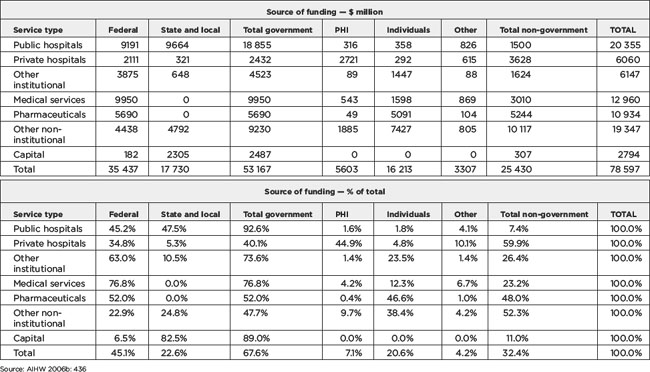

The share of total health care spending which comes from public funds and private health insurance (PHI), and from individuals and other sources (such as compensation funds and so on), is shown in Table 5.1. Of total health expenditure in 2003–04 of $78.6 billion, governments provided $53.2 billion, or about 67.6% of total health care spending. The Federal government contributed 45.1% ($35.4 billion), and the states, territories and local government about 22.6% ($17.7 billion). Direct contributions from individuals (also known as out-of-pocket expenditure) contributed 20.6% ($16.2 billion) and PHI funds 7.1% ($5.6 billion). Figure 5.1 also shows the expenditure shares from various funders.

Figure 5.1 Health expenditure by source of funds, Australia, 2003–04

Source: AIHW 2006b, Table S38, p 436

Some people are at greater risk than others of becoming sick and needing health care, and in some countries (such as the USA) it is possible for health insurers to ‘discriminate’ between people so that those who are perceived as more likely to get sick will pay a higher premium. This is the same principle that is used for car insurance. In the case of car insurance, young people, or people with a history of motor vehicle accidents, are thought to present a higher risk than people who have been driving for some time, or those with an established history of accident-free driving. Those presenting a perceived higher risk usually pay a higher premium to insure their car. The greater the perceived risk, the higher the premium. In Australia, this is not permitted in the case of health insurance. All members of health insurance funds pay the same premium regardless of their health status, a principle called community rating.

Under changes introduced by the Howard Liberal–National Coalition government from 1 July 2000 (the ‘lifetime health cover’ policy), health funds charge a higher rate for people who become members of health funds after they turn 30 years of age. This rate increases for each year that membership is delayed after the age of 30. This modified version of community rating is called ‘lifetime health cover’, and was introduced to encourage younger people to become health fund members. The reason for this is that young people are much less likely than older people to need health care. The more young people who join funds, the more money then becomes available to pay the health care costs of those who are more likely to need care. If the only people in a health insurance fund were older people who need a lot of care, the price of premiums would be very high. To a certain extent, this happened to PHI after the introduction of Medicare in 1984, because many people, particularly young people, saw little point in paying to be members of a fund they were unlikely to use, especially since Medicare was arguably seen as providing all necessary health care services and was funded through the tax system.

How does PHI fit with Medicare?

Medicare (see Chapters 1 and 3) provides access without charge to necessary treatment in public hospitals for Australian citizens and residents, and also provides a rebate for services provided by medical practitioners and for some services provided by some other practitioners. Medicare also provides financial ‘safety nets’ to guard against high out-of-pocket costs on medical expenses. The first of these provides for an increase in the amount rebated for medical expenses once the accumulated gap payments in any calendar year exceed $358.90 for an individual or family. The second, ‘Medicare plus’, safety net relates to the actual amount spent on medical services, and allows for a rebate of 80% of actual out-of-pocket expenses once these reach $519.50 per year (for relatively low income families eligible for a payment known as Family Tax Benefit) and $1039 for all others. These safety nets appear to provide a guarantee of access to medical service for people who need high levels of such care.

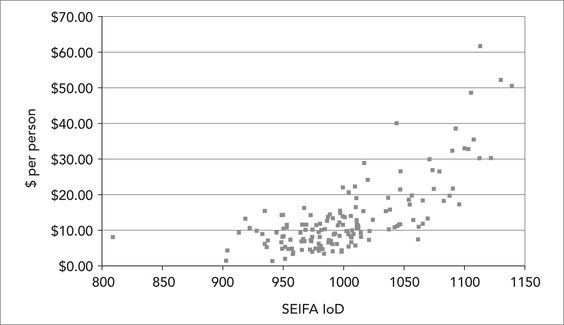

Unfortunately the available evidence demonstrates that the effect of these safety nets (particularly the ‘Medicare plus’ safety net) is to subsidise the relatively affluent rather than those most in need of services. Figure 5.2 shows the per capita distribution of Medicare safety net payments for 2006, using Federal electoral districts (usually referred to as ‘electorates’) ranked according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) ‘SEIFA’ index of comparative disadvantage. What this figure illustrates is that the wealthiest electorates in Australia (those with high SEIFA scores) receive a disproportionate amount of the safety net rebates, whereas the most disadvantaged electorates (those with low SEIFA scores) tend to receive very much lower average payments. This pattern is statistically significant, indicating that it is unlikely to have come about by chance.

Taken in conjunction with the policy measures adopted by the Liberal–Coalition Federal government to support PHI, these measures suggest that recent government policy attempted to shift the philosophical basis of Medicare away from its originally intended universalism towards a residualist approach, in which people are encouraged to personally carry more and more of the risk of medical and other health care costs, and to perceive Medicare not as the ‘normal’ system but rather as a safety net for those who can not afford to pay their own way. This development tends to also undermine the equitable principles of Medicare (and its predecessor, Medibank) (see Elliot 2003 for a discussion of Medicare’s underpinning policy philosophy).

Pause for reflection

Pause for reflection

Although Medicare is central to the Australian health care system, and very popular with Australians, its role seems to have become confused in recent years because of Government efforts to increase the level of PHI coverage. Some observers have suggested that the public system has been engineered into a ‘safety net’, rather than being seen as the main vehicle for the provision of health care to the Australian population. Even though the majority of the population continue to rely on Medicare to provide health care services, often well publicised problems with the public hospital system reinforce the idea that the public system is ‘failing’ under the pressure of demand. This may encourage those who wish to be sure of their access to necessary care to take out PHI cover.

The origins of Australia’s public–private health insurance mix

The Chifley government was defeated in 1949, and the Menzies government negotiated for some time to introduce a new scheme. A largely voluntary scheme was eventually implemented in 1953 — the Earle Page scheme — under which pensioners received fully subsidised health care, and others received a lesser subsidy for their health insurance contributions. The scheme was based on a fee-for-service model, meaning that medical practitioners remained free to charge whatever fee they thought appropriate. This scheme remained in effect during the 23 years of Coalition government (Scotton & Macdonald 1993: 12–13; Palmer & Short 1994: 60–1). Outside of Queensland, it left a minimum of 17% of the population uninsured, predominantly people from low income groups. Thus, the scheme was regressive (that is, it imposed a proportionately greater burden on the less well-off) and the co-payment required even for insured people was significant (around a third of medical expenses) and did not reduce for those who needed continuing care. It was also expensive and unnecessarily complex, according to the Nimmo committee which investigated the scheme and reported to Parliament in 1969 (Scotton & Macdonald 1993: 29).

Medibank to Medicare

Whitlam’s ALP government was defeated in late 1975 after the new Liberal leader, Malcolm Fraser, succeeded in forcing an early election. In 1976, in the first of a number of amendments, a provision to allow ‘opting-out’ was introduced, under which people could decide to take out private cover in lieu of Medibank. Those who did not take out PHI were charged a levy of 2.5% of taxable income. By 1981, the Fraser government had returned to a version of the pre-Medibank arrangements, reflecting the pressure that various interest groups had been able to exert on government, coupled with the government’s own desire to cut back public expenditure (Scotton 2000a). The Fraser government’s plan provided health care benefits only to pensioners on health care cards, those on sickness benefits, and those who passed an onerous means test. Everyone else had to have PHI, the cost of which attracted a 32% income tax rebate. Federal government grants to the states and territories for hospital care were substantially reduced, and hospitals were required to charge both inpatient and outpatient fees for all save a minority who qualified for free care. These arrangements were onerous, and brought about widespread hardship. The ALP at this time reaffirmed its commitment to universal health care, which was seen as an important component of the ALP’s election victory in 1983 (Scotton 2000a).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Pause for reflection

Pause for reflection

Pause for reflection

Pause for reflection