Chapter 15 Historical Roots of Primary Care in the United States Federal Government and Primary Care Primary Care Workforce Composition The Doctor of Nursing Practice Nurse Practitioner Role and Competencies in Primary Care Nurse Practitioners in Primary Care: A Role in Advanced Practice Nursing Advanced Practice Nurse Core Competencies Models of Primary Care and the Nurse Practitioner Role in Current Primary Care in the United States Aging Populations and Primary Care Care Transitions and Primary Care Quality of Care: Evidence-Based Care Role of Electronic Health Records in Primary Care Nurse Practitioners: Challenges and Opportunities This chapter provides an overview of the primary care nurse practitioner (NP) role. The primary care NP provides care for patients in diverse settings, including community-based settings such as private and public practices, acute, and long-term care settings across the life span. This chapter explores the historical context and evolution of primary care NP roles and settings and relates the NP role to the Institute of Medicine (IOM) definition of primary care (1996). Nurse practitioner competencies (National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties [NONPF], 2012) are used to operationalize NP practice in our ever-changing U.S. health care system, including the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) and accountable care organizations (ACOs). Exemplars of primary care practice are provided to demonstrate the integration of NP competencies into diverse primary care settings. Finally, information about role implementation and key issues confronting current primary care NPs is presented. Primary care had its origins in Britain about 100 years ago and is the foundation of most international health care systems, yet the vision for and outcomes of primary care in the United States actually lags far behind those of other developed countries (Macinko, Starfield, & Shi, 2003; Starfield, 1992) (See Figure 1). Historians remind us that at one time, all health care was once really primary care, and that in reality the United States, unlike other countries, developed a fixation on specialty care in the last century (Howell, 2010). Before World War II, most Americans’ health care was provided by a generalist physician and specialists would be seen only if referred. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, primary care expanded to include pediatricians, internists, and public health nurses (IOM, 1996). The use of the term primary care began in the late 1960s; at the same time, there was a growth in specialist physician care. It wasn’t until 1969 that family medicine was approved as a specialty, just after the first NP program started. The 1970s brought a rapid influx of capitated group practice models, or health maintenance organizations (HMOs), which emphasized primary care and lower hospitalization rates. The expansion of the HMO grew out of the Health Maintenance Organization Act of 1973, which intended to control expenditures for employers who offered health insurance benefits. Despite these efforts, primary care did not flourish for a number of reasons, one of which was that the role of primary care as gatekeeper was perceived as a barrier for patients’ access to specialty care by physicians. Today, patients who enroll in HMOs are often assigned to a primary care physician. Each full-time physician is assigned, or empanelled, with approximately 1500 patients to care for (Murray, Davies, & Boushon, 2007). Some HMOs and other third-party insurers do not empanel NPs or list them as primary care providers, rendering NPs’ contribution to primary care invisible. NP empanelment would provide a basis for measuring the effectiveness of NPs more accurately, whose services are often now significantly underestimated because they are recorded as being provided by their collaborating physicians (Naylor & Kurtzman, 2010; Pohl, Hanson, & Newland, 2010). More recently, the PCMH concept has been highly acclaimed as improving outcomes and management of complex chronic diseases (Nutting, Crabtree, Jaen, et al., 2009). It is a model of health care that embodies the full spectrum of primary care based on patient-centered care, clearly defined provider-patient relationships, and primary care standards of accessibility, continuity, comprehensiveness, integrated care, and interdisciplinary care (Keckley & Underwood, 2008). Most of primary care practice has been considered a cottage industry, with many small businesses (physician practices that employ NPs) that are not integrated vertically with other sectors of the health care system. Historically, NPs worked as employees in group physician practices who operated in a predominantly fee-for-service delivery system. With the move toward ACOs, this trend is likely to change. The relationship of NPs as employees of private, physician-owned businesses has led to the lack of data on NP primary care practice. Some primary care NPs are associated with academic or medical center primary care services, although a few are also connected with nurse-managed health centers (NMHCs) and other nurse-led primary care practices. Since the first primary care NP role, which focused on the care of children, a variety of primary care NP foci have emerged over 4 decades, emphasizing care to specific populations such as families, adults, older adults, and women. All these roles were conceived to increase access to primary care and address the needs of underserved populations. NPs have been acknowledged as high-quality, cost-effective providers of primary care (Brown & Grimes, 1993; Cook & Nolan, 1996; Laurant et al., 2005; Mundinger et al., 2000; Newhouse et al., 2011). The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), passed in 2010, has far-reaching goals to address access to care and emphasize primary care, including health promotion (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2011). It will be phased in over time, with comprehensive implementation by 2014, and will give an estimated 32 million more people in the United States access to health care. Because of its emphasis on primary care and the significant shortage of primary care physicians, NPs and other advanced practice nurses (APNs) will play a major role in providing access to quality care under the PPACA. It is expected that the PPACA will expand opportunities for the PCMH, community health centers (CHCs), NMHCs, and ACOs. These will be discussed later in the chapter. The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), an agency of the HHS, is the primary federal agency for improving access to health care services for people who are uninsured, isolated, or medically vulnerable. HRSA’s Bureau of Primary Care funds grants that build a safety net infrastructure in high-poverty counties, such as CHCs that provide primary health care, regardless of the person’s ability to pay. The Bureau of Health Professions funds grants to schools of nursing through its nursing education, practice, quality, and retention grants; their purpose is to provide support for academic, service, and continuing education projects, in part to increase nurse retention and strengthen the nursing workforce (HRSA, 2012a). Although this funding is not directed solely to primary care, it has helped fund NMHCs that provide primary care; often, these centers serve the underserved. About 20% of the U.S. population (60 million people) reside in health professional shortage areas (HPSAs). One criterion for this shortage designation is a community that has a population of 3500 but only one full-time primary care physician in one of the four primary care specialties—general or family practice, general internal medicine, pediatrics, and obstetrics and gynecology (Council of State Governments, 2008; HRSA, 2012b). Of those 60 million people living in HPSAs, about 34 million are considered to be medically underserved. Currently, NPs, certified nurse-midwives (CNMs), and physician assistants (PAs) are not included in the counts of primary care providers for the HPSA designation, for several reasons, but they are critically important for the APN community. First, there is concern that counting NPs and CNMs would render communities ineligible for a shortage designation because they would raise the eligibility ratio higher for communities that had APN(s) to more than the population-to-provider ratio of 3500 : 1, thus creating a catch-22. Second, the outdated state practice acts governing NP and CNM practice vary widely; some state laws permit independent APN practice, whereas others are highly restrictive. This variability across states introduces systematic bias in counting them as full-time equivalent primary care providers, because an APN in a restrictive state is not able to practice to full capacity because of restrictive laws. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, there is a substantial lack of data on the location and practice patterns of NPs. The IOM report, The Future of Nursing (2011), has identified this lack of data as critical for sound decision making. Individual NP organizations have tried to track data on their members, but there is no comprehensive national data set on NPs or APNs. The National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses in 2010 (based on data from 2008; Table 15-1) estimated that there were 250,527 registered nurses (RNs) prepared as APNs in one or more areas. Of these, 220,494 were employed in nursing (HRSA, 2010). NPs represented the largest group of APNs, approximately 154,000; this includes NPs who identify themselves as both a clinical nurse specialist (CNS) and NP. However, this figure is only an estimate of the NP primary care workforce because no national data have analyzed practicing NPs by specialty or focus (e.g., acute care, gerontology, family). The 2012 graduation data (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN] & NONPF, 2013), shown in Table 15-2, suggest that most NP graduates (82%) select primary care specialties. Although these graduation data do not fully inform the current workforce composition, they do suggest that most NPs choose primary care as their focus and are potential primary care workforce providers. The enrollment and graduation rate of NPs over the past 3 years continues to rise, with an annual graduation rate increasing overall by more than 1000 annually, and with most of the graduates prepared in primary care. This is a different picture from physician data. Family practice, for example, is the largest primary care specialty in medicine. Over the last 2 years, only 1184 and 1317 U.S. medical students each year chose residencies in family medicine (American Academy of Family Physicians [AAFP], 2011), compared with closer to about 12,000 primary care NPs graduating in 2012 (AACN & NONPF, 2013). These estimates, and the dearth of data on the NP workforce, make a compelling case for more robust workforce data on NP practice patterns, distribution, and impact on outcomes. However, the data we do have are compelling in terms of the key role that NPs will need to play in addressing the primary care needs of the nation with the implementation of the PPACA. Composition of the Primary Care Workforce *From U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Service Administration (HRSA). (2010). The registered nurse population: Findings from the March 2008 national sample survey of registered nurses (http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/rnsurvey2008.html). †Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2011). Occupational employment and wages, May 2011: 29-1071 Physician assistants (http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291071.htm). ‡Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Primary Care. (2011). Workforce facts and stats no. 1. The number of practicing primary care physicians in the United States (http://www.ahrq.gov/research/ pcwork1.htm). 2012 Graduates of Masters, Post-Masters, and Post-Baccalaureate DNP-Level Nurse Practitioner Programs* *Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding. From American Association of Colleges of Nursing and National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties. (2013). Annual survey. Washington, DC: Authors. In response to the need to support the advanced educational needs of the APN, the Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) is the expected requirement for APN preparation in the future. Endorsed by AACN, the DNP is a practice-focused doctorate designed to “prepare experts in specialized advanced nursing practice” (AACN, 2004). Foundational competencies and competencies in areas of specialization and role are included in DNP preparation. The DNP Essentials (AACN, 2006) outline specific foundational competencies and learning experiences in a variety of settings so that the broad consequences of decision making can be identified. These competencies are central to current APN practice and are particularly salient to primary care advanced practice. Many DNP programs started out as post-masters programs, but there are increasing numbers of post-baccalaureate programs that include NP preparation in their course of study. Although the numbers are still very small, they were included in the data presented in Table 15-2. Foundational to NP graduates overall, and specifically NPs in primary care, is that they have knowledge, skills, and abilities essential to independent and direct clinical practice (see Chapter 7, NONPF, 2012). The NP core competencies are acquired throughout an NP’s educational program through mentored patient care experiences, with emphasis on independent and interprofessional practice; analytic skills for evaluating and providing evidence-based, patient-centered care across settings, and advanced knowledge of the health care delivery system. Doctorally prepared NPs apply knowledge of scientific foundations in practice for quality care. They are able to apply skills in technology and information literacy and engage in practice inquiry to improve health outcomes, policy, and health care delivery. Areas of increased knowledge, skills, and expertise include advanced communication skills, collaboration, complex decision making, leadership, and the business of health care. The NONPF core competencies build on the APN competencies described in Chapter 3 and throughout this text. They also build on previous work that identified knowledge and skills essential to Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) competencies (AACN, 2006; NONPF & National Panel, 2006) and are consistent with the recommendations of the IOM report on The Future of Nursing (2011). Box 15-1 cross-maps the seven APN competencies from Chapter 3 and the nine NP core competencies (NONPF, 2012). The competencies described in the following section reflect some of the selected core competencies for all APNs, as presented in Chapter 3, as well as the nine NONPF core competencies for all NPs relevant to the NP in primary care (NONPF, 2012). The NONPF core competencies were developed by integrating existing Master’s and Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) core competencies. They are guidelines for educational programs preparing NPs to implement the full scope of practice as licensed independent practitioners. The competencies are essential proficiencies for all NPs and should be demonstrated on graduation. The competencies are specific to the NP role and prepare NPs, regardless of the population focus, to meet the complex challenge of translating rapidly expanding knowledge into practice and enable NPs to function in a changing health care environment. We will apply the APN and NP core competencies to the NP in primary care. For primary care NPs, one day is as varied as the next. Some days are filled with episodic visits and some days are spent predominantly on health care maintenance and education. The complexity of care and the NP’s familiarity with patients are cultivated over longitudinal encounters. Although the hallmark of the primary care NP’s practice is the breadth of health issues encountered, the privilege of patient-NP relationships occurs over time. This enables the NP to be patient-centered, tailor evidence-based interventions to the individual, and sustain a holistic practice. Characteristics of direct clinical practice, including the use of a holistic perspective, formation of therapeutic partnerships, expert clinical thinking, use of reflective practice, use of evidence as a guide to practice, and use of diverse approaches to guide practice are evidenced in the six exemplars in this chapter. Box 15-1 cross-maps direct clinical practice with the NONPF NP core competencies of independent practice and scientific foundations. • When is a patient ready to begin home glucose monitoring? • When is it time to suggest respite or home health care? • What is the right time to address sexuality issues with a preteen or teenager? • What is the right time to address an issue directly, and when is it time to back off from confronting difficult issues? Another important strategy for reflective practice is peer review if done in a supportive collaborative way and is included in the NONPF NP competency (see Box 15-1). Open transparent sharing and review of difficult and complex patient situations can lead to important self-reflection. The development of a holistic perspective is another feature of direct clinical practice. With increasing evidence of the importance of patient-centered care, and the broad definitions of primary care, a holistic, patient-centered approach is key for NPs in primary care. The exemplars in this chapter address this perspective extensively. In practice, APN core competencies (see Chapter 3) are often executed simultaneously to achieve the best outcome. However, for purposes of didactic discussion, specific competencies are discussed in the individual exemplars for clarity. The exemplars reflect the extent to which the core competencies enhance direct clinical practice, the core of primary care. The relationship between the primary care NP and the patient creates a strong foundation for the coaching and guidance competency (see Chapter 8). The coaching and guidance competency overlaps with the independent practice competencies and technology and information literacy NONPF NP competencies. A challenge for the primary care provider is to identify serious illness and involve other disciplines in the care of the complex patient. Exemplar 15-2, with LM, illustrates the coaching competency. It also shows how the NP collaborates with other health care professionals to provide comprehensive care to complex patients. In this case, LM’s NP may be the first provider to see the young adult with an eating disorder. Coaching and guidance is exemplified in Exemplar 15-1, in which CL (the NP) addresses the broad array of developmental and age-related concerns of a young adult who she has followed since her late teens. High-risk behaviors had been addressed in earlier years and prevention is consistently emphasized. A strong relationship has developed, with an emphasis on coaching and guidance. CL also uses NP competencies, such as scientific foundations and health delivery system competencies. Over the years, CL continues to develop the partnership with the patient. NPs have a deep knowledge of the change process and a menu of tools to use, depending on where the patient is in the cycle of change. Time is another tool for the primary care NP. As in the case of KI, the primary care NP is available to her longitudinally as she moves through developmental stages and health issues. Consultative relationships are critical to primary care NP practice. Relationships with other APNs, physicians, nurses, social workers, and other health care providers ensure that patients have access to comprehensive care. The exemplars illustrate different consultative relationships. In Exemplar 15-3, in which care is delivered in a nurse-managed health center, consultation is clearly evident through the use of technology and an electronic health record (EHR), making care seamless. Consultation can be formal, as reflected in Exemplar 15-3, or informal, with colleagues in one’s practice. This informal style is a frequent part of the daily rhythm of a nurse-managed center, as well as many primary care practices, and includes elements of the collaboration competency and independent practice. NPs in a smaller or solo practice may have to develop methods of consultation, as described in Exemplar 15-3. The increased use of technology in practice makes this more possible today. NPs in primary care use other APNs as a consultant in their specialty areas. For example, the primary care NP might initiate a consultation with a psychiatric NP or CNS to evaluate depression in a hospitalized patient. In Exemplar 15-2, psychiatric consultation was sought to address an eating disorder. A referral for consultation with a CNM for preconception counseling provides valuable information to the woman ready to start a family. Newly diagnosed patients with type 2 diabetes benefit from consultation with a CNS whose specialty is diabetes management, and the expertise of home health nurses is critical in discharge planning. Community health nurses have a wealth of knowledge regarding other community resources and insurance coverage for home care services. NPs often initiate consultations with other health care professionals, including physicians, pharmacists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, nutritionists, and social workers. The IOM definition of primary care (1996) implies the use of professional collaboration to deliver “integrated” and “accessible” care for all health care providers. The fiscal realities of practicing solo, in addition to the restrictions on NP practice imposed by state regulations, make a team approach the preferred choice for physicians and many nurses in primary care. Effective collaboration results in more comprehensive, patient-focused care (Bodenheimer & Grumbach, 2007) and it promotes high-quality, cost-effective outcomes (Cowan, Shapiro, & Hays et al., 2006). Most NPs practice in settings with physicians who are in a private practice or publicly funded practice, such as community health centers, the Veterans Administration (VA), or other government practices, including local health departments. Collaboration is seen as a professional ethic, central to primary care, and not easily regulated. All health professions collaborate on a regular basis to address the complex needs presented in primary care. It is an expected norm of primary care and not unique to NP practice. With the growth of the PCMH, collaborative and team practice will no doubt have an increasing prominence in primary care. Most of the exemplars in this chapter include some form of collaboration, but Exemplar 15-6 describes a gerontology practice based on collaboration among physicians, NPs, other nurses, pharmacists and social workers. The practice is intentionally interdisciplinary, exceptionally collaborative, and team-based. Patients benefit from a team approach although an NP or physician may be the leader of a group of patients. This exemplar demonstrates independent practice (NP NONPF competency) of an NP within a strong team–collaborative model of care. Patients clearly benefit from this approach to care and, in primary care, it is increasingly becoming more common in a PCMH. The work of the primary care NP is based on the premise that individuals seek care for a broad range of health care concerns over time across the life span. Relationships evolve over time (e.g., Exemplars 15-1 and 15-6), which facilitates a sense of mutual respect and trust (NONPF, 2012). Within that relationship, a deep understanding of the patient’s life and the meaning of the illness or health issue at hand develops. It is essential for NPs to know their patients’ lives, including their family members, their jobs and careers, and their challenges in raising children, as well as caring for aging parents. Nursing science foundations have contributed to the discipline of nursing, which is characterized by a “unique perspective, a distinct way of viewing all phenomena, which ultimately defines the limits and nature of its inquiry” (Donaldson & Crowley, 1978, p. 113). According to the AACN DNP Essentials (2006), specific middle-range theories should be used to guide the practice of NPs. Primary care NPs may use middle-range theory to guide their assessment, decision making, and interventions, particularly when situations call for them (Lenz, 1998). Historically, nursing professionals have struggled to close the theory-practice gap because of lack of knowledge, understanding, and applicability of nursing theory to guide nursing practice (Kenny, 2006). Doctorally prepared NPs, in particular, should be capable of understanding middle-range theory and translating research and other forms of information to improve practice processes and outcomes. Ultimately, primary care NPs must be able to develop new practice approaches based on the integration of research, theory, and practice knowledge. Primary care NPs, particularly doctorally prepared NPs, are expected to assume complex and advanced leadership roles to initiate and guide change. This competency is similar to the APN competency of clinical, professional and systems leadership (see Chapter 11). Their leadership should foster collaboration with multiple stakeholders (e.g. patients, families, community, integrated health care teams, policymakers) and demonstrate critical and reflective thinking. Collaboration and leadership are closely linked in the effort to improve health care. In primary care, for example, the NP’s direct clinical practice with expert coaching and guidance exemplifies a collaborative relationship between patient and NP. The 1996 IOM definition of primary care implies the use of professional collaboration to deliver integrated and accessible care. Effective collaboration results in more comprehensive, patient-focused care (Bodenheimer & Grumbach, 2007) and promotes high-quality, cost-effective outcomes (Cowan et al., 2006). The NP’s expert coaching and guidance also require the establishment of a collaborative relationship between patient and provider (Dick & Frazier, 2006). Expert clinical thinking and skillful performance are cultivated through repeatedly evaluating similar sets of health and illness scenarios and formulating plans of care based on patient expectations, standards of care, experience, clinical judgment, and current research. Primary NPs continuously synthesize knowledge and experience so that, over time, they acquire practical wisdom, defined by Oberle and Allen (2001) as “knowing when a particular action ought to be taken” (p. 151). Experienced APNs incorporate this practical wisdom into their decision making, taking actions that they might have been unlikely to take as novice practitioners. Primary care NPs play a critical leadership role in the translation of new knowledge into practice. To shorten the time spent translating bench science to bedside clinical practice, or for dissemination to population-based community interventions, primary care NPs are expected to provide leadership in translating new knowledge into practice and to generate knowledge from clinical practice to improve practice and patient outcomes. Thus, a primary care NP’s education should be sufficient to prepare her or him to apply clinical investigative skills to improve health outcomes and lead practice inquiry, individually or in partnership with others. Finally, the primary care NP should be able to disseminate evidence from such inquiry to diverse audiences using a number modalities. Practice inquiry and quality competencies are cross-mapped with the research competency of the APN in Box 15-1. There is extensive evidence linking information technology with improved patient safety, care quality, access, and efficiency (Fetter, 2009). Primary care NPs must demonstrate competencies in computers, informatics, and information literacy to use information technology for practice, education, and research. In particular, they need to be able to integrate appropriate technologies for knowledge management to improve health care and translate technical and scientific health information appropriate to various users’ needs. NPs rely on their technology and information literacy competencies to guide them in their assessments of patient and/or caregiver educational needs, in conjunction with the goal of effective, personalized health care. To serve as an expert primary care provider who coaches patients and caregivers toward positive behavioral change, primary care NPs need to demonstrate the use of information literacy skills in complex decision making. Exemplar 15-3 presents a situation in which technology and the use of the EHR enhance the care of a patient—that is, making timely consultation and referrals and consequently improving the outcomes of care for the patient. Their technology and information literacy competencies also inform NP contributions to the design of clinical information systems that promote safe, quality, and cost-effective care and enable NPs to use technology systems that capture data variables for the purpose of evaluating nursing care. The evolution of advanced nursing practice has been influenced by changes in health care delivery and policy. APNs play an important role in providing direction for policy associated with primary care. Research has shown that nurses’ involvement in the decision making of health care organizations is crucial for maximizing positive health outcomes for clients (Mackay, 2002). The development of key leadership skills is essential for primary care NPs to become more critically aware of underlying power structures in the health care system and ultimately to move toward being acknowledged as interdependent health professionals in primary care organizations. To play such a role, primary care NPs need to understand the interdependence of policy and practice. They need to able to advocate for ethical policies that promote access, equity, quality, and affordability. Furthermore, they must analyze the ethical, legal, and social factors that influence policy development and contribute to the development of health policy. Finally, primary care NPs should be able to analyze the implications of health policy across disciplines and evaluate the impact of globalization on health care policy development. Health care delivery in the United States has often been characterized by fragmentation at the national, state, community, and practice levels. There is no unified entity or set of policies that guide the greater health care system. To keep pace with the complex demands of today’s sicker and higher acuity patients, primary care NPs need to be competent within health delivery systems. In particular, they must be able to apply knowledge of organizational practices and complex systems to improve health care delivery. According to the Commonwealth Fund Commission (Davis, 2005), this fragmentation has divided providers’ responsibilities among a number of agencies; that is, although providers may practice in the same community and care for the same patients, they often work independently from one another. The fragile primary care system in the United States has been on the verge of collapse. To minimize risk to patients and providers at the individual and systems level, primary care NPs should effect health care change using broad-based skills, including negotiating, consensus building, and partnering. For example, primary care NPs can help patients and families navigate different providers and care settings. They need to facilitate the development of health care systems that address the needs of culturally diverse populations, providers, and other stakeholders. The primary care NP may encounter patient care concerns that raise ethical issues. This competency is cross-mapped with the APN ethical decision making competency. Examples include reproductive issues, informed consent, individuals excluded from the health insurance market, and conflicting health care goals among family members. NPs have opportunities to engage in preventive ethics by initiating discussions about advance directives and organ donation with patients in a relaxed and thoughtful manner, before they become pressing issues. In addition, NPs identify and address ethical conflicts that arise when clinical goals conflict with institutional goals (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2001; Johnson, 2005; McCaughan, Thompson, Cullum, et al., 2005; Ulrich, Soeken, & Miller, 2003). Primary care NPs are accountable primarily to their patients and honor patient confidentiality at all times. This professional value has become the focus of more intense government regulation and scrutiny with the implementation of the 1996 Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Primary care NPs must be vigilant in their protection of confidential patient information in whatever form it takes. In an era of managed health care, the primary care clinician’s accountability to the health care system in which he or she practices may create tension, especially with the use of resources for patient care. Primary care NPs must always be ethically accountable for their actions, particularly when financial incentives related to resource use are involved (Bodenheimer & Grumbach, 2007). Illness can create a range of negative emotions in patients, including anxiety, fear, powerlessness, and vulnerability. In the ever-expanding health care system, primary care NPs increasingly face ethical issues, particularly involving, but not limited to, the allocation of care. How to resolve these ethical issues is becoming an important task for NPs who work in primary care settings. Nursing practice must embrace thoughtful reflection on the meaning of moral concepts in terms of culture and diversity. Moral values are native to a particular culture and influence one’s beliefs about health, illness, and how to set health care priorities (Pierce, 1997). Operating with a context-sensitive approach can enable primary care NPs to understand ethical issues in nursing practice more easily and to integrate ethical principles into their decision making (Lützén, 1997). Primary care NPs need to evaluate the ethical consequences of decisions and apply ethically sound solutions to complex issues related to diverse individuals, populations, and systems of care.

The Primary Care Nurse Practitioner

Historical Roots of Primary Care in the United States

Federal Government and Primary Care

Health Resources and Services Administration

Health Professional Shortage Areas Designation

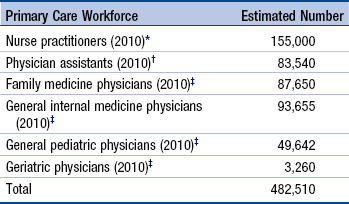

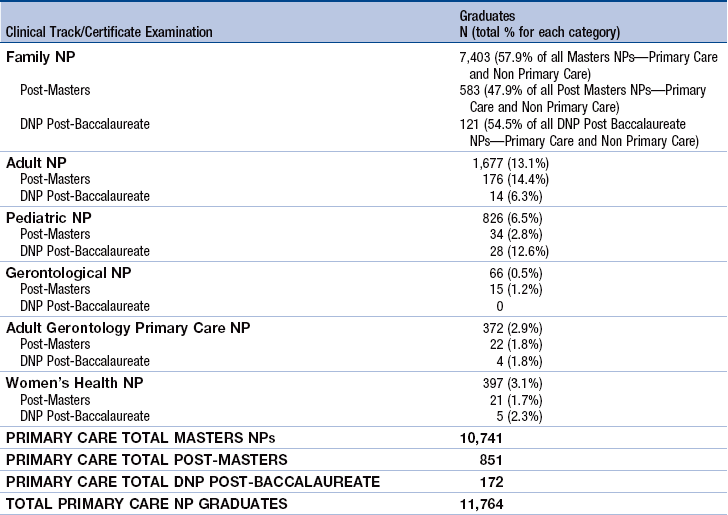

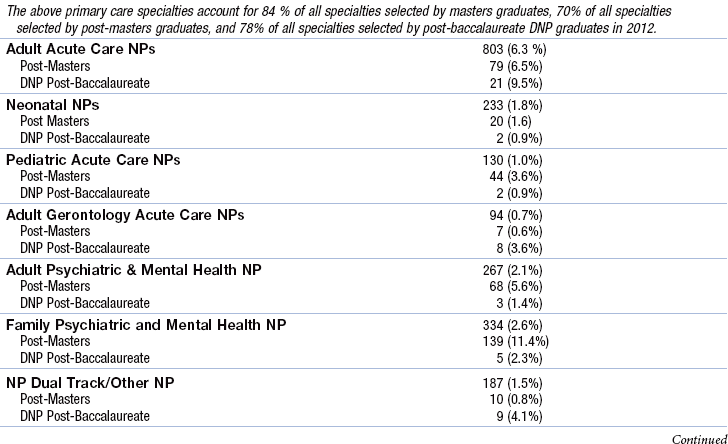

Primary Care Workforce Composition

![]() TABLE 15-1

TABLE 15-1

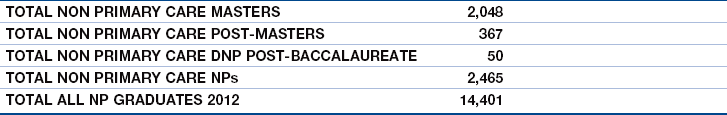

![]() TABLE 15-2

TABLE 15-2

The Doctor of Nursing Practice

Nurse Practitioner Role and Competencies in Primary Care

Nurse Practitioners in Primary Care: A Role in Advanced Practice Nursing

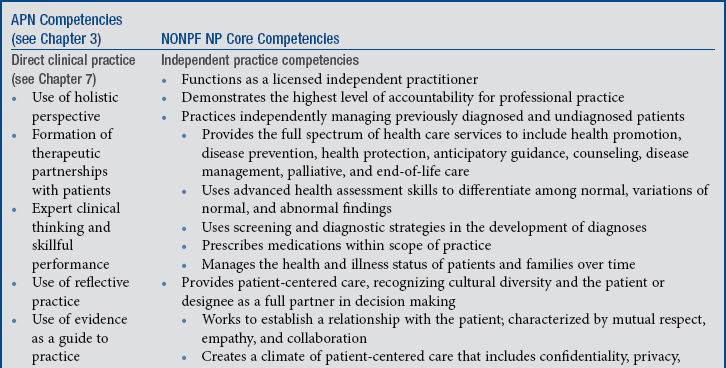

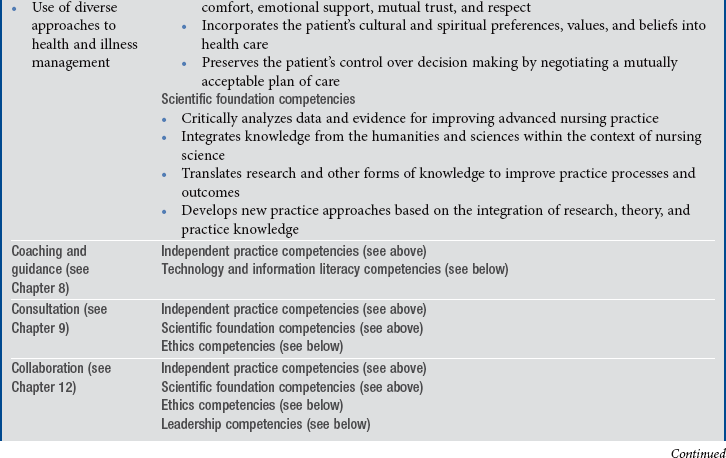

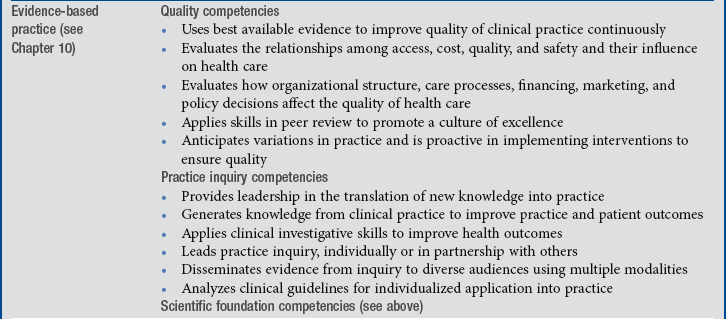

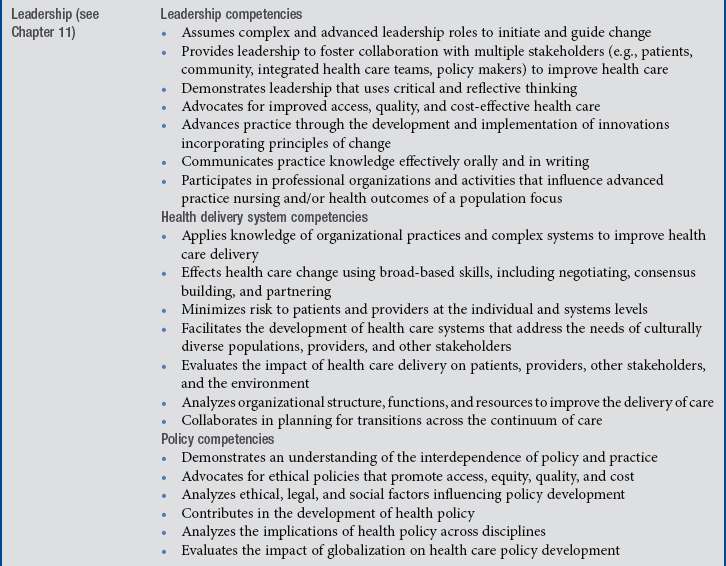

Advanced Practice Nurse Core Competencies

Direct Clinical Practice

Reflective Practice: A Component of Direct Patient Care

Holistic Perspective

Coaching and Guidance

Consultation

Collaboration

Nurse Practitioner Core Competencies

Independent Practice Competencies

Scientific Foundation Competencies

Leadership Competencies

Practice Inquiry Competencies

Technology and Information Literacy Competencies

Policy Competencies

Health Delivery System Competencies

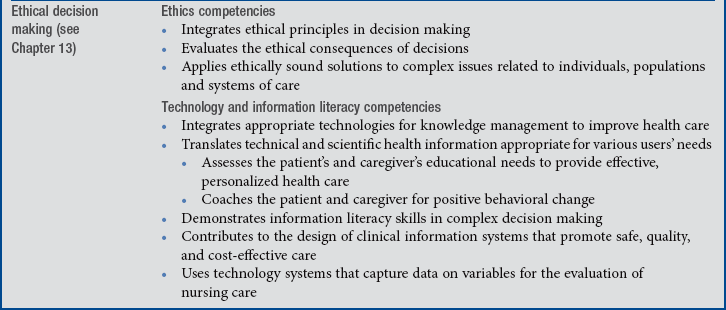

Ethics Competencies

The Primary Care Nurse Practitioner

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access