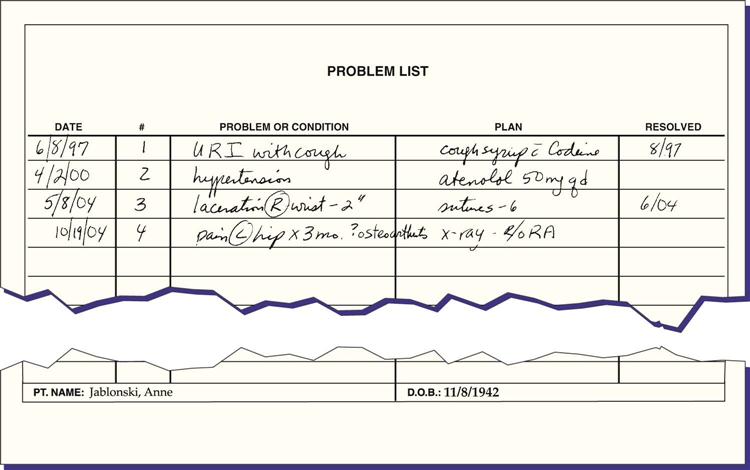

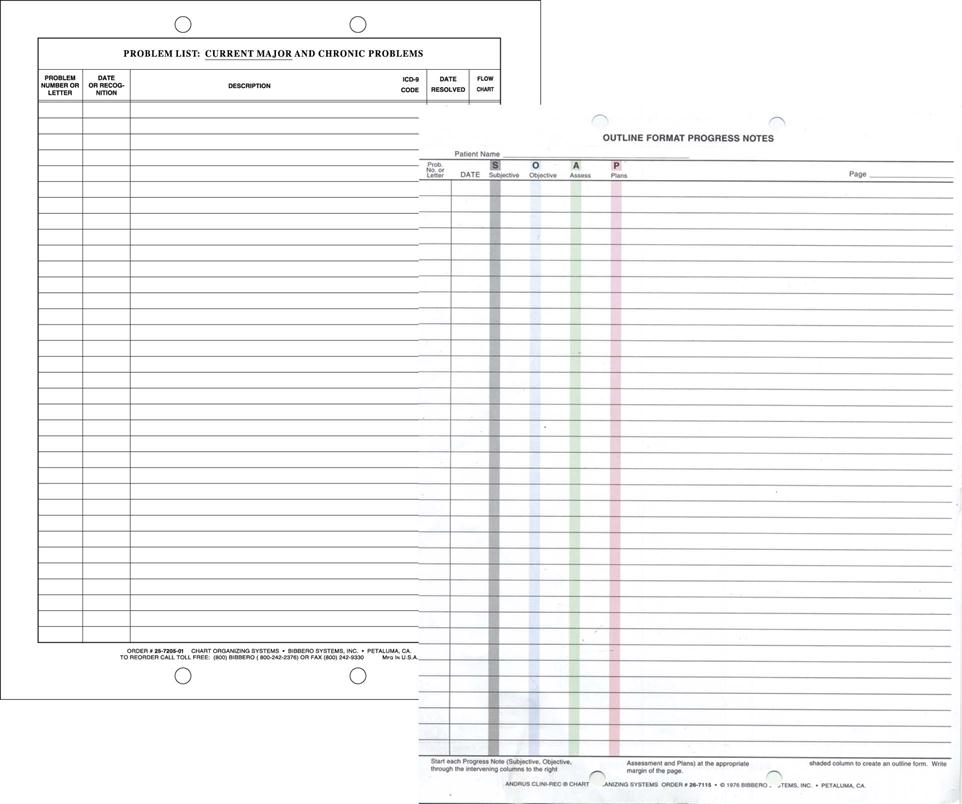

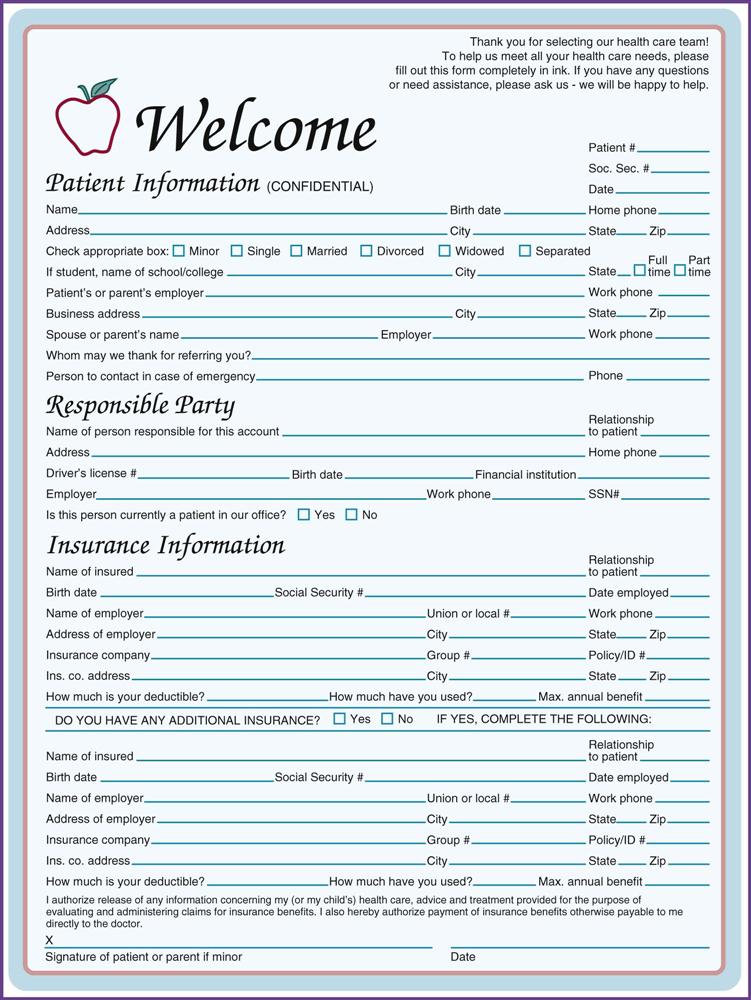

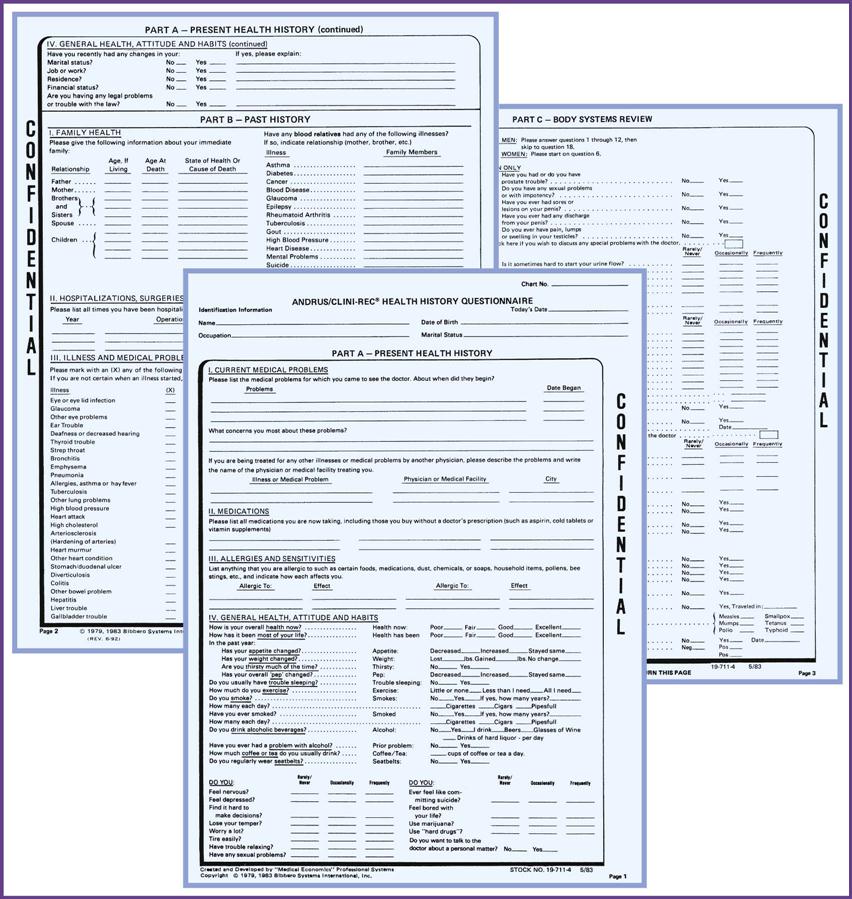

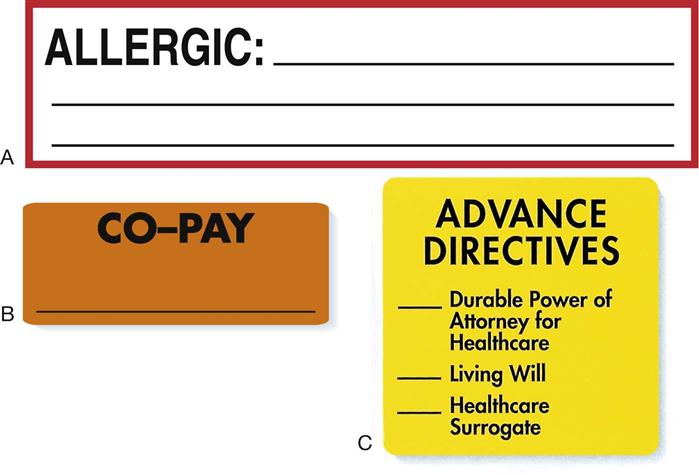

1. Define, spell, and pronounce the terms listed in the vocabulary. 2. State several reasons accurate medical records are important. 3. Explain who owns the medical record. 4. Explain how to document appropriately and accurately. 5. Explain the difference between a traditional medical record and a problem-oriented medical record. 6. Explain how to establish and organize a patient’s medical record. 7. Identify systems for organizing medical records. 8. Differentiate between subjective and objective information. 9. Describe various types of information kept in the medical record. 10. Explain how to make additions to a medical record. 11. Discuss correction of an entry in the patient’s record. 12. Identify both equipment and supplies needed to file medical records. 13. Discuss filing procedures. 15. Discuss the pros and cons of various filing methods. 16. Identify types of records common to the healthcare setting. alphabetic filing Any system that arranges names or topics according to the sequence of the letters in the alphabet. alphanumeric Of or relating to systems made up of combinations of letters and numbers. augment To make greater, more numerous, larger, or more intense. caption A heading, title, or subtitle under which records are filed. chronologic order Of, relating to, or arranged in or according to the order of time. continuity of care Continuation of care smoothly from one provider to another, so that the patient receives the most benefit and no interruption in care. dictation (dik-tay′-shun) The act or manner of uttering words to be transcribed. direct filing system A filing system in which materials can be located without consulting an intermediary source of reference. gleaned Gathered bit by bit (e.g., information or material); picked over in search of relevant material. indirect filing system A filing system in which an intermediary source of reference (e.g., a card file) must be consulted to locate specific files. microfilm A film with a photographic record of printed or other graphic matter on a reduced scale. numeric filing The filing of records, correspondence, or cards by number. objective information Information gathered by watching or observing a patient. obliteration (uh-bli-tuh-ra′-shun) The act of making undecipherable or imperceptible by obscuring or wearing away. OUTfolder A folder used to provide space for the temporary filing of materials. OUTguide A heavy guide used to replace a folder temporarily removed from the filing space. power of attorney A legal instrument authorizing a person to act as the attorney or agent of the grantor. pressboard A strong, highly glazed composition board resembling vulcanized fiber; heavy card stock. procrastination (pruh-kras-tuh-na′-shun) Intentional postponement of doing something that should be done. provisional diagnosis A temporary diagnosis made before all test results have been received. purging The process of moving active files to inactive status. quality control An aggregate of activities designed to ensure adequate quality, especially in manufactured products or in the service industries. requisites (re′-kwuh-zuhts) Entities considered essential or necessary. retention schedule A method or plan for retaining or keeping medical records and for their movement from active, to inactive, to closed filing. reverse chronologic order Arranged in order so that the most recent item is on top and older items are filed further back. subjective information Information gained by questioning the patient or taking it from a form. tickler file A chronologic file used as a reminder that something must be dealt with on a certain date. transcription A written copy of something made either in longhand or by machine. vested Granted or endowed with a particular authority, right, or property; to have a special interest in. Susan Beezler has just begun her career in the medical assisting profession. She is attending medical assisting school in the morning and works part-time for a family practitioner in the afternoons as a clerical record assistant. Susan is eager to learn about medicine and looks forward to taking on more responsibility at the office. The practice is growing swiftly and recently added a new physician, Dr. Alex Thomas. Dr. Thomas has enjoyed working with Susan and feels that her energy will be just what his patients need. He has taken a professional interest in Susan and often lets her assist him with patients when her other duties allow. Susan knows that although she is a beginner in the office, she will gain trust from her supervisors and patients as long as she projects a teachable attitude. The office has not yet converted to an electronic records system, so Susan uses the information she learned in school about paper medical records. She cheerfully performs filing and even does some transcription for Dr. Thomas. The other staff members are pleased with her willingness to perform the most mundane tasks. Susan enjoys sharing her experiences with her classmates. She is the only one currently working in the medical field, and the other students ask her lots of questions about the “real world” of medicine. She is very careful not to breach patient confidentiality; she discusses situations only in general, never mentioning any patients’ names. Susan feels a great sense of pride that she is already a member of the healthcare team and able to contribute to the lives of her patients. While studying this chapter, think about the following questions: A medical records management system is only as good as the ease of retrieval of the data in the files. A fast pace is the norm in the medical office; therefore, staff members must be able to find patients’ medical records quickly, and the records must be functional so that the needed information can be obtained easily. Few things are more frustrating to the patient than being told, “We cannot locate your records.” Patients have every right to question the competence of the medical care they are receiving if the office has problems simply finding a chart. Organization and adherence to set routines help ensure that medical records are accessible when needed. In today’s medical facilities, records are either paper based or computer based. The versatile medical assistant is knowledgeable about both systems and able to perform well with either. Medical records are kept for four basic reasons. First, the medical record helps the physician provide the best possible medical care for the patient. The physician examines the patient and enters the findings in the patient’s medical record. These findings are clues to the diagnosis. The physician may order many types of tests to confirm or augment the clinical findings. As the reports of these tests come in, the findings fall into place, much like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. Then, with the confirmation data to support the diagnosis, the physician can prescribe treatment and form an opinion about the patient’s chances of recovery, assured that every resource has been used to arrive at a correct judgment. The medical record provides a complete history of all the care given to the patient. The medical record also provides critical information for others. By reading through the record and discovering the methods used to treat the patient, healthcare professionals can provide continuity of care. Each person knows what the patient has experienced and can provide continuous care, even from one facility to another. For example, when a patient is transferred from a hospital to a skilled nursing facility, the information from the patient’s hospital record helps the nursing facility staff to better care for the patient. When patients move from place to place or caregivers change, copies of the pertinent information should move with the patient to provide this continuity of care. Second, medical records are kept as legal protection for those who provided care to the patient. A documented medical record is excellent proof that certain procedures were performed or that medical advice was given. An accurate record is the foundation for a legal defense in cases of medical professional liability. This is one reason writing legibly in the record and documenting exactly what happened to the patient, in addition to the provider’s response, are critical. Remember: If it isn’t charted, it didn’t happen (Procedure 14-1). Third, medical records provide statistical information that is helpful to researchers. The patient’s record provides information about medications taken and the reactions to them. Medical records may be used to evaluate the effectiveness of certain kinds of treatment or to determine the incidence of a given disease. Physicians often take part in drug studies that track adverse reactions and side effects. The effects of various treatments and procedures also can be tracked and statistics gleaned from the information gathered from patients’ records. Correlation of such statistical information may result in a new outlook on some phases of medicine and can lead to revised techniques and treatments. The statistical data from medical records also are valuable in the preparation of scientific papers, books, and lectures. Fourth, medical records are vital for financial reimbursement. The information in the medical record supports claims for reimbursement and is required by most third-party payers. Who owns the medical record? Patients often assume that because the information in the medical record is about them, ownership of the record rightfully is theirs. However, the owner of the physical medical record is the physician or medical facility, often called the “maker,” that initiated and developed the record. The patient has the right of access to the information within the record but does not own the physical chart or other documents pertaining to the record. The patient has a vested interest and therefore has the right to demand confidentiality of all information placed in the chart. The actual medical record should never leave the medical facility where it originated. Even the physician should refrain from taking the record from the office to the hospital or nursing facility. If information from the record is needed, copies can be placed in a file, and progress notes can be written on site and inserted into the original record later. Patients’ records should be kept in a locked room or locked filing cabinets when the office is closed. Written medical records must be legible. Each record should be written as if the physician and staff expect it to eventually be involved in a lawsuit; therefore, every word must be legible to an average reader years after written. The record can help the physician prove that he or she treated a patient in a competent manner, or it can prove that the patient was not given competent care. Every person on staff at the physician’s office is responsible for writing legibly in every medical record. The medical records management system should provide an easy method of retrieving information. The files should be organized in an orderly fashion The information also must be accurate, and corrections should be made and documented properly. The wording in the record should be easily understood and grammatically correct. An efficient method of adding documents to the chart must be established so that the physician or other provider always has the most up-to-date information. Above all, the medical records management system must work for the individual facility. The two major types of patient records are the paper medical record and the electronic medical record. As computer technology advances, the paper medical record seems more and more inefficient. It is difficult to use a paper-based record for multiple purposes. In most cases, only one person at a time can use the paper record. Misfiled information is common, and the entire record also can be misfiled. Data cannot be accessed easily for research and quality control, and in facilities with multiple departments, the information is difficult to share. The paper-based record is good evidence of patient care, but it is not nearly as useful in other capacities. The electronic medical record (also called the electronic health record) is much more efficient than the paper record. Chapter 15 covers the electronic medical record in more detail. The traditional patient record is source oriented; that is, observations and data are cataloged according to their source—physician, laboratory, radiology department, nurse, technician—with no recording of a logical relationship among them. Forms and progress notes are filed in reverse chronologic order (most recent on top) and in separate sections of the record according to the type of form or service rendered (e.g., all laboratory reports together, all x-ray reports together, and so on). Some files are placed in chronologic order; that is, the items inside are filed according to the order of time. However, most patient files are in reverse chronologic order so that the physician and staff members do not have to search to the bottom of the chart to find a recent lab report on a test. The problem-oriented medical record (POMR) is a departure from the traditional system of keeping patient records. It sometimes is referred to as the Weed system, because it was originated by Dr. Lawrence L. Weed, a professor of medicine at the University of Vermont College of Medicine. The POMR is a record of clinical practice that divides medical action into four bases: Several companies have developed file folders for organizing patient data according to the POMR (Figure 14-1). The problem list is entered on the divider cover for laboratory reports. Special sections are provided for current major and chronic problems and for inactive major or chronic problems. The divider cover for progress notes is a chart for listing medications and other therapeutic modalities. Progress notes follow the SOAP approach. SOAP is an acronym for the following: Some medical offices also use an E in the record to represent evaluation; others include E for education and R for response. The education notation documents that the patient was educated about his or her condition or given a patient information sheet. The response section is used to record an assessment of the patient’s understanding of and possible compliance with the treatment plan. The POMR has the advantage of imposing order and organization on the information added to a patient’s medical record. The records are more easily reviewed, and the likelihood of overlooking a problem is greatly reduced. The SOAP method forces a rational approach to the patient’s problems and assists the formulation of a logical, orderly plan of patient care (Figure 14-2). The POMR has continued to grow in popularity since its introduction in the 1970s. It is especially advantageous in clinics, group practices, and hospitals, where more than one person must be able to find essential information in the chart. Note that the SOAP method often is used in the POMR. Some facilities use the CHEDDAR method in medical records. CHEDDAR signifies the following: The physician decides which recording method he or she prefers, and the medical assistant must conform to that standard. The office policy and procedures manual provides specific instruction, if the standard used is different from one the medical assistant has used in the past. Never hesitate to ask the physician if you are unclear about any part of the documentation standard. The medical case history is the most important record in a physician’s practice. For completeness, each patient’s record should contain subjective information provided by the patient and objective information provided by the physician. If all entries are completed, the case history will stand the test of time. No branch of medicine is exempt from the need to keep patient history records. The patient’s case history begins with routine personal data, which the patient usually supplies on the first visit when the medical record is established (Procedure 14-2). Most patients are required to complete a patient information form (Figure 14-3). The basic facts needed are: • Patient’s full name, spelled correctly • Names of parents if the patient is a child • Home address, telephone number, and e-mail address • Business address and telephone number • Employment information for spouse • Healthcare insurance information The personal and medical history, which often is obtained by having the patient complete a questionnaire, provides information about any past illnesses or surgery the patient has had and about injuries or physical defects, whether congenital or acquired (Figure 14-4). It also includes information about the patient’s daily health habits. Stickers can be used on the front of the medical record to indicate allergies, advance directives, and other information (Figure 14-5). These are useful for helping the health professional keep important facts about the patient in the forefront of the mind while treating the individual. The family history comprises the physical condition of the various members of the patient’s family, any illnesses or diseases individual members may have had, and a record of the causes of death. This information is important, because certain diseases may have a hereditary pattern. Most physicians are interested in the immediate family: children, parents, grandparents, and siblings. The social history includes information about the patient’s lifestyle. If the patient drinks, how many drinks per day or per week are consumed? If the patient smokes cigarettes, how many packs a day are smoked? Drug use and even marital information can be considered part of the social history. The patient’s chief complaint is a concise account of the patient’s symptoms, explained in the patient’s own words. It should include the following: • The nature and duration of pain, if any • When the patient first noticed the symptoms • The patient’s opinion about the possible causes of the problem • Remedies the patient may have applied before seeing the physician • Whether the patient has had the same or a similar condition in the past • Other medical treatment received for the same condition in the past Most medical facilities use a pain scale to determine the severity of the patient’s discomfort. The medical assistant might ask, “How bad is your pain on a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 being almost no pain, and 10 being the worst pain you’ve ever experienced?” The pain scale or wording used in individual facilities should be documented in the office policy and procedures manual and followed by the medical assistant. Objective findings, sometimes referred to as signs, become evident from the physician’s examination of the patient. These findings can be observed and measured. After the physician has examined the patient, the physical findings are recorded in the history. The results of other tests or requests for these tests are then recorded or, if they appear on separate sheets, are attached to the history. Based on all the evidence provided in the patient’s past history, the physician’s examination, and any supplementary tests, the physician notes his or her diagnosis of the patient’s condition in the medical record. If some doubt remains, this may be labeled a provisional diagnosis. A differential diagnosis is the process of weighing the probability of one disease causing the patient’s illness against the probability that other diseases are causative. For example, the differential diagnosis of rhinitis, or a runny nose, could indicate allergic rhinitis (hay fever), the common cold, or even abuse of drugs or nasal decongestants. The physician’s suggested treatment is listed after the diagnosis. Generally, instructions to the patient to return for follow-up treatment within a specific period also are noted here. If surgery or other treatment is needed, the patient must sign a consent form (Procedure 14-3). On each subsequent visit, the date must be entered on the chart, and information about the patient’s condition and the results of treatment, based on the physician’s observations, must be added to the history. Notations of all medications prescribed or instructions given, and the patient’s own progress report, should be placed in the record. Any home visits are noted. If the patient is hospitalized, the name of the hospital, the reason for admission, and the dates of admission and discharge are recorded. Much of this information can be obtained from the hospital discharge summary. When the treatment is terminated, the physician records that information. For example: August 18, 2013. Wound completely healed. Patient discharged. The medical assistant usually collects the routine personal data. The personal and medical history and the patient’s family history may be obtained by asking the patient to complete a questionnaire, with the physician augmenting the information provided during the patient interview. When the medical assistant is responsible for recording the patient’s history, care must be taken to ensure that the patient’s answers are not heard by others in the reception room. If privacy is not possible, the patient should be given a form to fill out, and the information should be transferred to the permanent record later. When privacy is available, the medical assistant may ask the patient questions and write or type the answers directly into the record. This method offers an opportunity to become better acquainted with the patient while completing the necessary records. If new patients must complete a lengthy questionnaire, the questionnaire may be mailed to the patient with a request that it be completed and returned to the physician before the appointment. If the record is to be computerized, requesting the information ahead of time gives the office staff the opportunity to transfer information to the computer before the new patient’s visit. The patient’s chief complaint may have been indicated to the medical assistant, but the physician will question the patient in more detail. Many practitioners write their own entries on the chart in longhand. Some may type the findings directly into the computer. Others may dictate the material, either directly to the medical assistant or by using a recording device. If the material is dictated and typed, the physician should check each entry and then initial the entry to verify its accuracy. For a chart to be admissible as evidence in court, the person dictating or writing the entries must be able to attest that they were true and correct at the time they were written. The best indication of this is the physician’s signature or initials on the typed entry. As long as a patient is under the physician’s care, the medical history is building. Each laboratory report, radiology report, and progress note is added to the record, with the latest information always on top (Procedure 14-4). Although each item is important, the most recent usually is most significant to the patient’s care. Again, the physician should read and initial each of these reports before it is placed in the record.

The Paper Medical Record

Learning Objectives

Vocabulary

Scenario

The Importance of Accurate Medical Records

Ownership of the Medical Record

Creating an Efficient Medical Records Management System

Types of Records

Organization of the Medical Record

Source-Oriented Records

Problem-Oriented Medical Records

Contents of the Complete Case History

Subjective Information

Personal Demographics

Personal and Medical History

Patient’s Family History

Patient’s Social History

Patient’s Chief Complaint

Objective Information

Physical Examination Findings and Laboratory and Radiology Reports

Diagnosis

Treatment Prescribed and Progress Notes

Condition at the Time of Termination of Treatment

Obtaining the History

The Medical Assistant’s Role

Making Additions to the Patient’s Record

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access