The Origins of Health Insurance

Chapter objectives

After completion of this chapter, the student should be able to:

1. Explain health (medical) insurance.

2. Discuss the early development of health insurance in the United States.

3. Outline the important changes in the evolution of health insurance.

4. List and explain today’s key health insurance issues.

5. Explain how people can obtain health insurance, and what situations affect their access to it.

6. Examine issues affecting cost of healthcare.

Chapter terms

Accountable Care Organization

Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA)

cost sharing

deductible

entity/entities

fee-for-service

group plans

health insurance

Health insurance exchange

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)

Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) Act

indemnify

indemnity insurance

indigent

insurance

insured

insurer

managed healthcare

medical insurance

policy

preexisting conditions

premium

preventive medicine

What is insurance?

To understand medical insurance, you have to know a little about insurance in general. First, let’s look at a typical definition of insurance:

“The act or business, through legal means (normally a written contract), of protecting an individual’s person or property against loss or harm arising out of specified circumstances in return for payment, which is called a premium.”

The insuring party (called the insurer) agrees to indemnify (or reimburse) the insured for loss that occurs under the terms of the insurance contract.

Now that we know that insurance is basically financial protection against loss or harm, let’s break it into smaller pieces. Insurance, as we know it, is a written agreement called a policy, between two parties (or entities), whereby one entity (the insurance company) promises to pay a specific sum of money to a second entity (often an individual, or it could be another company) if certain specified undesirable events occur. Examples of undesirable events include a windstorm blowing a tree over on a house, a car being stolen, or—as in the case of medical insurance—an illness or injury. In return for this promise for financial protection against loss, the second entity (the insured) periodically pays a specific sum of money (premium) to the insurance company in exchange for this protection.

Now that you now have a better understanding of what insurance is in general, let’s look at medical insurance (or health insurance, as it is frequently called). Medical insurance narrows down the “undesirable events” mentioned earlier to illnesses and injuries. The insurance company promises to pay part (or sometimes all, depending on the policy) of the financial expenses incurred as a result of medical procedures, services, and certain supplies performed or provided by healthcare professionals if and when an individual becomes sick or injured. Some insurance policies also pay medical expenses even if the individual is not sick or injured. Healthcare providers and companies that sell health insurance have determined that it is often less costly to keep an individual well or to catch an emerging illness in its early stages, when it is more treatable, than to pay more exorbitant expenses later on should that individual become seriously ill. This practice is referred to as preventive medicine.

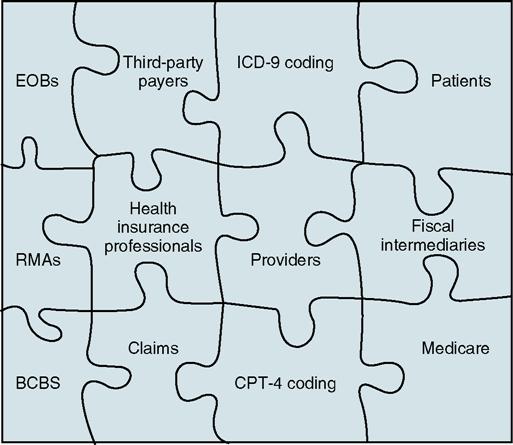

The term medical (health) insurance should not cause students to become apprehensive when they hear it. A good analogy to put medical insurance into perspective might be to compare it with a picture puzzle. When the individual puzzle pieces are dumped onto a table, there is little meaning or continuity to the jumble of pieces lying haphazardly on the tabletop. Then slowly, as the pieces are assembled, a picture begins to take shape and the puzzle starts making sense. Similarly, medical insurance can be perplexing as individual concepts are presented, but when you “look at the whole picture,” it becomes clearer and more understandable. As we begin to appreciate how the puzzle pieces fit together, we can understand the whole picture more easily when the puzzle is at last completed. Fig. 1-1 illustrates how the “medical insurance puzzle” is assembled.

History

Insurance is not a recent phenomenon. The word insurance is derived from the Latin word securitas, which translates into the English word security.

From the beginning of time, people have looked for ways to ease some of the hardships of human existence. It has been common knowledge down through the ages that it has been difficult for any one individual to survive for long on his or her own. Prehistoric humans quickly learned that to survive, the resources of others must be pooled.

The beginnings of modern health insurance occurred in England in 1850, when a company offered coverage for medical expenses for bodily injuries that did not result in death. By the end of that same year in the United States, the Franklin Health Assurance Company of Massachusetts began offering medical expense coverage on a basis resembling health insurance as we know it now. By 1866, many other insurance companies began writing health insurance policies. These early policies were mostly for loss of income and provided health benefits for a few of the serious diseases that were common at that time—typhus, typhoid, scarlet fever, smallpox, diphtheria, and diabetes. People did not refer to these arrangements as insurance, but the concept was the same.

In the United States, the birth of health insurance came in 1929 when Justin Ford Kimball, an official at Baylor University in Dallas, Texas, introduced a plan to guarantee schoolteachers 21 days of hospital care for $6 a year. Other employee groups in Dallas soon joined the plan, and the idea caught on nationwide. This plan eventually evolved into what we now know as Blue Cross. The Blue Shield concept grew out of the lumber and mining camps of the Pacific Northwest at the turn of the 20th century. Employers, wanting to provide medical care for their workers, paid monthly fees to “medical service bureaus,” which were composed of groups of physicians. The Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans traditionally established premiums by community rating—that is, everybody in the community paid the same premium.

To explore more interesting and detailed facts related to the history of insurance, refer to the list of websites at the end of this chapter.

Metamorphosis of medical insurance

If you ever took a biology course, you may remember how certain insects go through several stages—from the caterpillar to the pupa and from the pupa to the adult butterfly. This is called metamorphosis. By definition, metamorphosis is “a profound change in form from one stage to the next in the life history of an organism.” The transformation of health insurance from what it was in the beginning to what we know it to be today can be compared to this metamorphosis, although the transformation of health insurance as it was in the beginning into what it has evolved in the 21st century certainly does not resemble that of a caterpillar into beautiful butterfly—perhaps more that of an ugly duckling into the proverbial swan. To illustrate this changing process, Table 1-1 presents a health insurance timeline.

Table 1-1

| 1900s | American Medical Association (AMA) becomes a powerful national force. Membership increases from about 8000 physicians in 1900 to 70,000 in 1910—half of them in the U.S. This is the beginning of “organized medicine.” Surgery is becoming more common. Physicians are no longer expected to provide free services to all hospital patients. United States lags behind European countries in finding value in insuring against costs of sickness. Railroads are the leading industry to develop extensive employee medical programs. |

| 1910s | U.S. hospitals are now modern scientific institutions, valuing antiseptics and cleanliness, and using medications for the relief of pain. American Association for Labor Legislation (AALL) organizes first national conference on “social insurance.” Progressive reformers gaining support for health insurance. Opposition from physicians and other interest groups and the entry of the United States into World War I in 1917 undermine reform front. |

| 1920s | Reformers emphasize the cost of medical care instead of wages lost to sickness—the relatively higher cost of medical care is a new and dramatic development, especially for the middle class. Growing cultural influence of the medical profession—physicians’ incomes are higher, and prestige is established. Rural health facilities are seen by many as inadequate. Penicillin is discovered, but it will be 20 years before it is widely used to combat infection and disease. |

| 1930s | The Depression changes priorities, with greater emphasis on unemployment insurance and “old age” benefits. Social Security Act is passed, omitting health insurance. Against the advice of insurance professionals, Blue Cross begins offering private coverage for hospital care in dozens of states. |

| 1940s | Penicillin comes into use. Prepaid group healthcare begins, seen as radical. To compete for workers, companies begin to offer health benefits, giving rise to the employer-based system in place today. Congress is asked to pass an “economic bill of rights,” including the right to adequate medical care. President offers a single-system, national health program plan that would include all Americans. |

| 1950s | Attention turns to Korea and away from health reform; United States has a system of private insurance for people who can afford it and welfare services for the poor. Federal responsibility for the sick is firmly established. Many more medications are available now to treat a range of diseases, including infections, glaucoma, and arthritis, and new vaccines become available that prevent dreaded childhood diseases, such as polio. The first successful organ transplantation is performed. |

| 1960s | In the 1950s, the price of hospital care doubled. Now in the early 1960s, people outside the workplace, especially the elderly, have difficulty affording insurance. More than 700 insurance companies sell health insurance. Major insurance endorses high-cost medicine. President signs Medicare and Medicaid into law. Number of physicians reporting themselves as full-time specialists grows from 55% in 1960 to 69%. |

| 1970s | Prepaid group healthcare plans are renamed health maintenance organizations (HMOs), with legislation that provides federal endorsement, certification, and assistance. Healthcare costs escalate rapidly; U.S. medicine is now seen as in crisis. Growing complaints by insurance companies that the traditional fee-for-service method of payment to physicians is being exploited. Healthcare costs rise at double the rate of inflation. Expansion of managed care helps to moderate increases in healthcare costs. |

| 1980s | Overall, there is a shift toward privatization and corporatization of healthcare. Under President Reagan, Medicare shifts to payment by diagnosis (DRG) instead of by treatment. Private plans quickly follow suit. Growing complaints by insurance companies that the traditional fee-for-service method of payment to physicians is being exploited. A specific fee or payment amount per patient (capitation) to physicians becomes more common. |

| 1990s | Healthcare costs rise at double the rate of inflation. Expansion of managed care helps moderate increases in healthcare costs. By the end of the decade, 44 million Americans—16% of the nation—have no health insurance at all. Human Genome Project to identify all of the > 100,000 genes in human DNA gets under way. By June 1990, 139,765 people in the United States have HIV/AIDS, with a 60% mortality rate. |

| 2000s | Healthcare costs continue to rise. Medicare is viewed by some as unsustainable under the present structure and must be “rescued.” Changing demographics of the workplace lead many to believe the employer-based system of insurance cannot last. The Human Genome Project’s identification of all of the > 100,000 genes in human DNA was completed in 2003, and all individual chromosome papers were completed in 2006; papers analyzing the genome continue to be published. Direct-to-consumer advertising for pharmaceuticals and medical devices is on the rise. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree