Chapter 9

The Oral Cavity and Pharynx

Look to thy mouth; diseases enter here.

George Herbert (1593–1632)

General Considerations

The mouth and oral cavity are used by individuals to express an entire range of emotions. As early as infancy, the mouth provides gratification and sensory pleasure.

Approximately 20% of all visits to primary care physicians are related to problems of the oral cavity and throat. Most patients with these problems present with throat pain, which may be acute and associated with fever or difficulty in swallowing. A sore throat may be the result of local disease, or it may be an early manifestation of a systemic problem.

It has been estimated that more than 90% of patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) have at least one oral manifestation of the disease. It appears that as further immunologic impairment develops, the risk of oral lesions increases. There are several important oral manifestations that are strongly associated with early HIV infection. The presence of any of them mandates HIV testing.

Oral cancer is the largest group of those cancers that fall into the head and neck cancer category. It is estimated that in 2013, 42,000 people in the United States will be newly diagnosed with oral cancer. This includes those cancers that occur in the mouth itself, the oropharynx, and on the exterior lip of the mouth. There is a 2 : 1 male-to-female incidence ratio, with oral cancer representing approximately 3% of all new cancer cases in men. This is the fifth year in a row in which there has been an increase in the rate of occurrence of oral cancers; in 2007 there was a major jump of over 11% in that single year. Worldwide, the problem is much greater: more than 600,000 new cases are diagnosed annually.

Although some believe that oral cancer is rare, it will be newly diagnosed in approximately 100 new individuals each day in the United States alone, and a person dies from oral cancer every hour of every day. Cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx was responsible for 7900 deaths in 2011. The rate of death from oral cancer is relatively high because the cancer is routinely discovered late in its development, with metastases to other areas or invasion deep into local structures. Oral cancer is also particularly dangerous because it has a high risk of producing second primary tumors. This means that patients who survive a first encounter with the disease have up to a 20 times higher risk for development of a second cancer. Death rates have, however, been decreasing continuously in both men and women over the past three decades.

For all stages combined, approximately 84% of persons with oral cancer and pharynx cancer survive 1 year after diagnosis. The 5-year and 10-year relative survival rates are 61% and 51%, respectively. There are several pathologic types of oral cancers, but approximately 90% are squamous cell carcinomas. It was estimated in 2010 that approximately $3.2 billion was spent in the United States on the treatment of head and neck cancers.

There are two distinct etiologic factors by which most people develop oral cancer. One is through the use of tobacco and alcohol. The second is human papillomavirus (HPV). Recent studies have shown that incidence is increasing for oral cancers associated with HPV type 16 infection among white men younger than 50 years of age. This is the same virus responsible for the vast majority of cervical cancers in women. A small percentage of people (less than 7%) develop oral cancers from no currently identified cause.

Although the exact cause of tongue cancer remains unknown, it most often occurs in people who use tobacco products (cigarettes, cigars, pipes, and smokeless tobacco), consume alcohol (especially when combined with tobacco use), or chew betel nuts. Chewing of betel nuts, discussed later in this chapter, is not a common practice in the United States, but it is a widespread habit in many parts of the world, especially in Taiwan and India (see Fig. 9-51). HPV infection is associated with cancer of the tonsil, base of the tongue, and other sites of the oropharynx.

In 2012, there were 12,360 new cases of laryngeal cancer in the United States with 3650 deaths attributed to it. There is a clear association between smoking, excess alcohol ingestion, and the development of squamous cell cancers of the larynx. For smokers, the risk of the development of laryngeal cancer decreases after the cessation of smoking but remains elevated even years later when compared with that of nonsmokers. Supraglottic cancers typically present with sore throat, painful swallowing, referred ear pain, change in voice quality, or enlarged neck nodes. Early vocal cord cancers are usually detected because of hoarseness. Prognosis for small laryngeal cancers that have not spread to lymph nodes is very good with cure rates of 75% to 95% depending on the site, tumor bulk, and degree of infiltration.

The clinical picture of the obstructive sleep apnea syndrome has long been recognized without an understanding of the disease process. The term “Pickwickian syndrome” that is sometimes used for the syndrome was coined by the famous early twentieth century physician, Sir William Osler, who must have been a reader of Charles Dickens. The description of Joe, “the fat boy” in Dickens’s novel The Pickwick Papers, is an accurate clinical picture of an adult with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. The early reports of obstructive sleep apnea in the medical literature described individuals who were very severely affected, often presenting with severe hypoxemia, hypercapnia, and congestive heart failure. The Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study estimated in 1993 that roughly 1 in every 15 Americans is affected by at least moderate sleep apnea. It also estimated that in middle-age as many as 9% of women and 24% of men are affected, undiagnosed, and untreated. The National Commission on Sleep Disorders Research estimated that minimal sleep apnea affects 7 to 18 million people in the United States and that relatively severe cases affect 1.8 to 4 million people. The prevalence increases with age. Sleep apnea remains undiagnosed in approximately 92% of affected women and 80% of affected men.

The costs of untreated sleep apnea reach further than just health issues. It is estimated that in the United States the average untreated sleep apnea patient’s annual health care costs $1336 more than an individual without sleep apnea. This may cause $3.4 billion per year in additional medical costs.

Many physician visits for oral problems are associated with psychiatric disturbances. Psychosomatic disease symptoms often center on the mouth. Patients with psychosomatic disease may complain of “burning” or “dryness” of the mouth or tongue. Bruxism, or grinding of the teeth other than for chewing, occurs especially during sleep. This overuse of the muscles of mastication has often been interpreted as a manifestation of rage or aggression that is not overtly displayed; it may also be an infantile response to reduce psychic tension. Bruxism can produce facial pain, which causes further spasm of the muscles and continued bruxism, resulting in a vicious circle. Individuals who habitually have something in their mouths, such as a pipe, a thumb, or a pencil, may cause damage to their oral cavities.

Although it is often thought that the oral cavity is examined only by dentists, other health care professionals must have competency in evaluating this important region of the body. The health care provider must be able to accomplish the following:

2. Recognize dental caries and periodontal disease.

4. Recognize oral manifestations of systemic disease.

5. Recognize systemic problems caused by oral disease and procedures.

6. Assess physical findings concerning the range and smoothness of jaw motion.

7. Identify dental appliances.

8. Know when a dental consultation is required or should be postponed because of a medical problem.

Structure and Physiologic Characteristics

The Oral Cavity

The oral cavity consists of the following structures:

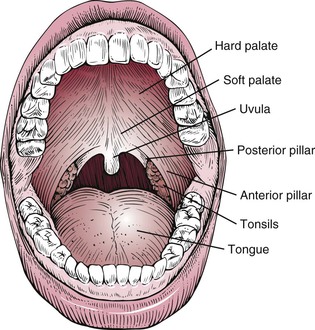

The oral cavity extends from the inner surface of the teeth to the oral pharynx. The hard and soft palates form the roof of the mouth. The soft palate terminates posteriorly at the uvula. The tongue lies at the floor of the mouth. At the most posterior aspect of the oral cavity lie the tonsils, between the anterior and posterior pillars. The oral cavity is illustrated in Figure 9-1.

The buccal mucosa is a mucous membrane that is continuous with the gingivae and lines the insides of the cheeks. The linea alba, or bite line, is a pale or white line along the line of dental occlusion. It may be slightly raised and show impressions of the teeth.

Lips are red as a result of the increased number of vascular dermal papillae and the thinness of the epidermis in this area. An increase in desaturated hemoglobin, cyanosis, is manifested as blue lips. The common blue discoloration of the lips in a cold environment is related to the decreased blood supply and increased extraction of oxygen.

The tongue lies at the floor of the mouth and is attached to the hyoid bone. It is the main organ of taste, aids in speech, and serves an important function in mastication. The body of the tongue contains intrinsic and extrinsic muscles and contains the strongest muscle of the body. The tongue is supplied by the hypoglossal, or twelfth cranial, nerve.

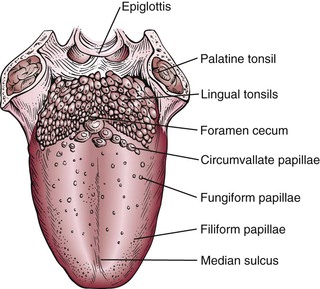

The dorsum of the tongue has a convex surface with a median sulcus. Figure 9-2 shows the tongue viewed from above. At the posterior portion of the sulcus is the foramen cecum, which marks the area of the origin of the thyroid gland. Behind the foramen cecum are mucin-secreting glands and an aggregate of lymphatic tissue called the lingual tonsils. The texture of the tongue is rough as a result of the presence of papillae, the largest of which are the circumvallate papillae (Fig. 9-3). There are approximately 10 of these round papillae, which are located just in front of the foramen cecum and divide the tongue into the anterior two thirds and the posterior one third. Filiform papillae are the most common papillae and are present over the surface of the anterior portion of the tongue. The fungiform papillae are located at the tip and sides of the tongue. These papillae can be recognized from their red color and broad surface.

The taste buds are located on the sides of the circumvallate and fungiform papillae. Taste is perceived from the anterior two thirds of the tongue by the chorda tympani nerve, a division of the facial nerve. The glossopharyngeal, or ninth cranial, nerve perceives taste sensation from the posterior third of the tongue. There are four basic taste sensations: sweet, salty, sour, and bitter. Sweetness is detected at the tip of the tongue. Saltiness is sensed at the lateral margins of the tongue. Sourness and bitterness are perceived at the posterior aspect of the tongue and are carried by the glossopharyngeal nerve.

When the tongue is elevated, a mucosal attachment, the frenulum, may be seen underneath the tongue in the midline connecting the tongue to the floor of the mouth.

The hard palate is a concave bone structure. The anterior portion has raised folds, or rugae. Figure 9-4 shows the palatal rugae. The soft palate is a muscular, flexible area posterior to the hard palate. The posterior margin ends at the uvula. The uvula aids in closing off the nasopharynx during swallowing.

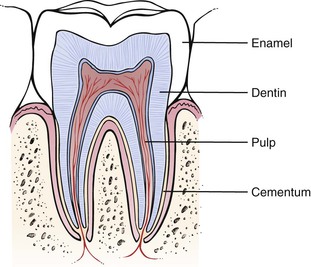

Teeth are composed of several tissues: enamel, dentin, pulp, and cementum. Enamel covers the tooth and is the most highly calcified tissue in the body. The bulk of the tooth is the dentin. Under the dentin is the pulp, which contains branches of the trigeminal, or fifth cranial, nerve and blood vessels. The cementum covers the root of the tooth and attaches it to the bone. Figure 9-5 shows a cross section through a molar tooth.

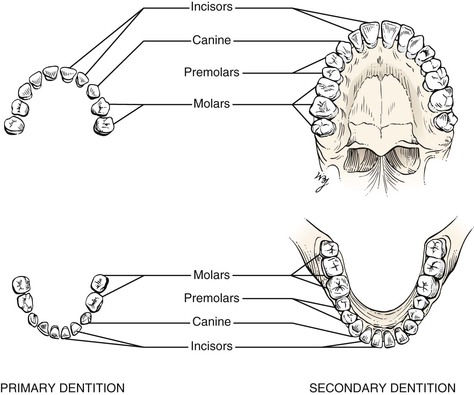

The primary dentition, or the deciduous teeth, consists of 20 teeth that erupt from the ages of 6 to 30 months. The primary dentition per quadrant of jaw consists of two incisors, one canine, and two premolars. These teeth are shed from the ages of 6 to 13 years. The secondary dentition, or the permanent teeth, consists of 32 teeth that erupt from the ages of 6 to 22 years. The secondary dentition per quadrant of jaw consists of two incisors, one canine, two premolars, and three molars. Figure 9-6 illustrates the primary and secondary dentition, and Table 21-4 summarizes the chronology of dentition.

Although not part of the oral cavity proper, the salivary glands are considered part of the mouth. There are three major salivary glands: the parotid, the submandibular, and the sublingual glands. The parotid gland is the largest of the salivary glands. It lies anterior to the ear on the side of the face. The facial, or seventh cranial, nerve courses through the gland. The duct of the parotid gland, Stensen‘s duct, enters the oral cavity through a small papilla opposite the upper first or second molar tooth. The submandibular gland is the second largest salivary gland. It is located below and in front of the angle of the mandible. The duct of the submandibular gland, Wharton‘s duct, terminates in a papilla on either side of the frenulum at the base of the tongue. The sublingual gland is the smallest of the major salivary glands. It is located in the floor of the mouth, beneath the tongue. There are numerous ducts of the sublingual gland, some of which open into Wharton’s duct. In addition to these major salivary glands, there are hundreds of very small salivary glands located throughout the oral cavity.

The Pharynx

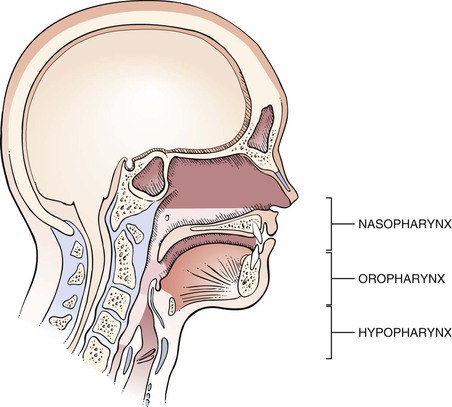

The pharynx is divided into the nasopharynx, the oropharynx, and the hypopharynx. The nasopharynx lies above the soft palate and is posterior to the nasal cavities. On its posterolateral wall is the opening of the eustachian tube. The adenoids are pharyngeal tonsils and hang from the posterosuperior wall near the opening of the eustachian tube. The oropharynx lies below the soft palate, behind the mouth, and superior to the hyoid bone. Posteriorly, it is bounded by the superior constrictor muscle and the cervical vertebrae. Below the oropharynx is the area known as the hypopharynx (or laryngopharynx). The hypopharynx is surrounded by three constrictor muscles, which are innervated by the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves. The hypopharynx ends at the level of the cricoid cartilage, where it communicates with the esophagus through the upper esophageal sphincter. Figure 9-7 illustrates the functional parts of the pharynx.

The muscular walls of the pharynx are formed by the constrictor muscles, which function during the act of swallowing. The blood supply is derived from the external carotid artery.

Lymphatic tissue is abundant in the pharynx. The lymphoid tissue consists of the palatine tonsils, the adenoids, and the lingual tonsils. These tissues form Waldeyer‘s ring. The palatine tonsils lie in the tonsillar fossa, between the anterior and posterior pillars. The palatine tonsils are almond-shaped and vary considerably in size. The adenoids lie on the posterior wall of the nasopharynx, and the lingual tonsils are located at the base of the tongue. The upper portion of the pharynx drains to the retropharyngeal nodes, and the lower part drains to the deep cervical lymph nodes.

The functions of the pharynx are as follows:

Swallowing, or deglutition, is divided into three stages. The voluntary stage occurs when a bolus of food is forced by the tongue past the tonsils to the posterior pharyngeal wall. The second stage is involuntary constriction by the pharyngeal muscles, propelling the bolus from the pharynx to the esophagus. The third stage is also involuntary, in which the esophageal muscles push the bolus down into the stomach. The larynx is first raised and then closed during the first two stages of swallowing. The eustachian tubes open during swallowing when the nasopharynx closes.

The pharynx also acts as a structure of resonation and articulation. Resonation refers to the vibration of a structure. Articulation is the change in shape of a structure to produce speech. Contracting the pharyngeal muscles causes a change in the acoustic quality of speech. Changes in the size and shape of the pharynx affect resonance. The soft palate affects resonance by opening and closing the partition between the oral and nasal cavities. If closure is incomplete, nasal speech results.

The Larynx

The larynx is located at the superior margin of the trachea and below the hyoid bone, which is located at the base of the tongue. The larynx is at the level of the fourth to sixth cervical vertebrae. The larynx functions as a guard against the entrance of solids and liquids into the trachea, as well as being the organ of voice production.

The epiglottis is attached above the larynx. The function of the epiglottis is generally believed to be protection of the airway during swallowing.

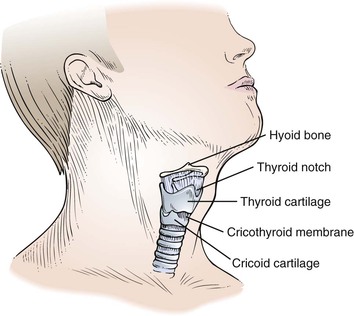

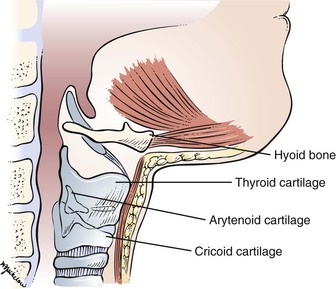

The body of the larynx consists of a series of cartilaginous structures: the thyroid, the cricoid, and the arytenoid cartilages. The thyroid cartilage forms the bulk of the structure of the larynx and produces the prominence in the neck known as the Adam‘s apple. Toward the top of the thyroid cartilage is the thyroid notch. Farther down on the thyroid cartilage, there is a space, the cricothyroid space and membrane, that separates the thyroid cartilage from the cricoid cartilage. The cricoid cartilage articulates with the cricothyroid membrane superiorly and the trachea inferiorly. It is the only complete ring of cartilage in the larynx. The paired arytenoid cartilages provide an important area for attachment of the vocal cords. A diagram of the thyroid and cricoid cartilages onto the neck is illustrated in Figure 9-8, and the laryngeal skeleton is illustrated in Figure 9-9.

Review of Specific Symptoms

The Oral Cavity

All patients should be asked the following:

“When did you last see a dentist?”

“Have you any pain, sores, or masses on your lips or in your mouth that do not heal?”

“Have you had any problems after extraction of a tooth?”

(If the patient wears dentures) “Have you noticed any change in the way your dentures fit?”

Cancers of the oral cavity are most often found in people who are older than 45 years of age. Cancer of the lip is more common in men than in women and is more likely to develop in people with light-colored skin who have spent extensive time in the sun. Cancer of the oral cavity is more common in people who chew tobacco or smoke pipes. A possible sign of a cancer of the mouth or gums is when dentures no longer fit well.

The most important symptoms of disease of the oral cavity are as follows:

Pain

When a patient complains of oral pain, it is important to ask the following:

“Do you feel the pain anywhere else?”

“How long has the pain been present?”

“What makes it better? Worse?”

Tooth pain may be a symptom of underlying gingival disease. A history of dental procedures and recent dental work should be documented.

Pain in the teeth may sometimes be referred from the chest. Patients with angina may actually complain of pain in their teeth associated with exertion. Careful and thoughtful questioning is indicated.

Ulceration

Oral ulcerative lesions are common and may be manifestations of local or systemic disease of immunogenic, infectious, malignant, or traumatic origin. The patient’s history is important because it indicates whether the lesions are acute or chronic, single or multiple, and primary or recurrent.

“Have you had a lesion like this before?”

“How long have the lesions been present?”

“Are there lesions anywhere else on the body, such as in the vagina? In the urethra? In the anus?”

“Do you smoke?” If so, “How much?”

The examiner should ask about a patient’s sexual habits. These questions were discussed in Chapter 1, The Interviewer’s Questions. Smoking and drinking alcohol predispose an individual to precancerous lesions of the mouth, such as leukoplakia and erythroplakia.

Bleeding

Bleeding may result from a primary hematologic disorder or from a local inflammation or neoplasm. Many medications may also cause or predispose a patient to bleeding. Always ask whether the patient is taking any medications.

Mass

If a patient complains of, or on physical examination is found to have, an intraoral mass or a mass in the region of a salivary gland, determine its duration and whether the mass is painful. A painless mass is usually a sign of a tumor.

Are there associated symptoms such as excessive salivation, known as ptyalism, or dryness of the mouth, known as xerostomia? Is dysphagia (difficulty in swallowing) present?

Halitosis

Halitosis affects approximately 50% of all adults. Fortunately, in only a small percentage does the problem persist the entire day. Most individuals with halitosis are told by others that they have bad breath, although they themselves may be unaware of the problem. In some cases, the odor in the mouth is so objectionable that it can compromise the patient’s social and professional life.

The source of bad breath is in the oral cavity in 90% of cases; the other 10% have disorders in the nasal passages or lungs or a systemic disease. It is questionable whether the gastrointestinal tract is a source of halitosis.

It is believed that halitosis is caused by volatile sulfur and other compounds exhaled into the air during speech and respiration. These compounds are produced by putrefactive, gram-negative anaerobic bacteria colonizing on the posterior dorsum of the tongue, in periodontal pockets, and around some dental restorations and prostheses. The volatile sulfur compounds are generated by the bacterial metabolism of sulfur-containing amino acids. Xerostomia increases the level of volatile sulfur compounds.

Patients with systemic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, cirrhosis, uremia, and cancer; infections of the perioral regions; and trimethylaminuria (fish odor syndrome) can suffer from bad breath. These conditions must be considered in the absence of oral and sinonasal disease.

Treatment of halitosis should be directed toward the underlying cause. Once it has been determined that the source of the bad breath is the oral region, the patient should be instructed in procedures of good oral hygiene, including proper tooth brushing, flossing, and, most important, cleaning of the posterior dorsum of the tongue with a special scraping device or toothbrush. Appropriate mouthwash may also be used. These procedures must be performed at least twice a day to remove the bacteria and accumulated metabolic products.

Xerostomia

Xerostomia, or dry mouth, is a common symptom of reduced or absent salivary secretion. It is most common in women and in aging populations. It is frequently observed as a side effect of various medications, including antihistamines, decongestants, tricyclic antidepressants, antihypertensives, and various anticholinergic medications. It may also occur with mouth breathing, neurologic disorders, radiation therapy to the head and neck, HIV infection, and autoimmune disorders. The saliva is thick, and the oral mucosal surfaces are dry; the tongue is commonly fissured and atrophic. The dry environment predisposes to candidiasis and dental caries.

The Pharynx

The most common symptoms of disease of the pharynx include the following:

Nasal Obstruction

Nasal obstruction can result from enlarged adenoids or from tumor formation in the nasopharynx. It is important to determine whether the patient has any allergies or sinus trouble or has sustained nasal trauma.

Pain

Pain can result from inflammation of the tonsils or posterior pharynx, as well as from a tumor in this area. Acute throat pain may be caused by inflammatory processes or injury. A foreign body in the pharynx often produces severe pain that is worsened by swallowing. Often, throat pain may be referred to the ipsilateral ear. Chronic throat pain may be caused by inflammatory processes, as well as by neoplasms. Enlarged thyroid lobes or diffuse thyroid enlargement may cause throat pain associated with dysphagia. Hysteria is another cause of chronic throat pain.

Dysphagia

Dysphagia is difficulty in swallowing. Determine the site of obstruction. Does the dysphagia occur with liquids, solids, or tablets? Questions related to tonsillar infections are relevant because enlarged tonsils may interfere with swallowing. It is prudent to ask whether regurgitation of food occurs; this results from an abnormal pharyngeal pouch. The patient may say that the “food gets stuck.” This is often associated with significant disease.

Deafness

A tumor at the distal end of the eustachian tube in the nasopharynx can produce conductive deafness. Benign masses such as hypertrophied adenoids may be responsible. Nasopharyngeal malignancies may also be the cause of conductive deafness. In many cases, serous effusions in the middle ear space cause eustachian tube dysfunction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree