Chapter 22

The Geriatric Patient

Old age isn’t so bad when you consider the alternative.

Maurice Chevalier (1888–1972)

General Considerations

The geriatric patient is an individual 65 years of age or older. Among such individuals, there is considerable variation in general health, mental status, functional ability, personal and social resources, marital status, living arrangements, creativity, and social integration. The age range of this rapidly growing population spans more than 40 years. The world’s geriatric population is currently increasing at a rate of 2.5% per year—significantly faster than the total population. Between 1900 and 2000, the number of Americans older than 65 years increased from a little more than 3 million to 35 million. Since 1960, the geriatric population has grown 107%, in comparison with 50% for the U.S. population as a whole. From 2000 to 2040, in the United States, the number of people 65 years of age or older is projected to increase from 34.8 million to 77.2 million. It is estimated that in the developed nations of the world, there are 146 million people 65 years of age and older. This group will increase to 232 million by the year 2020.

A decreasing rate of mortality, especially from heart disease and stroke, and a reduction in risk factors such as smoking, high blood pressure, and high serum cholesterol levels have contributed to this increased survival.

The population older than 85 years of age represents the fastest-growing segment of the U.S. population. This “graying of America” is expected to continue. By the year 2020, one fifth of the population will be older than 65 years of age. These statistics are extremely important in view of the cost of medical care for this population. Currently, 32% of all health care dollars is spent on the geriatric population, which constitutes only 12% of the total population.

Some other statistics are important. Eighty-nine percent of older adults are white. Older adult women outnumber older men 1.5 : 1 overall and 3 : 1 among individuals 95 years of age and older. African Americans constitute 12% of the total U.S. population but only 8% of the older age groups. In 1986, most older men (77%) were married, whereas most older women (52%) were widows. Fifteen percent of older men live alone, in comparison with 40% of women. Nursing home residents account for 5% of the population older than 65 years. Approximately 12% of the population older than 65 years of age continue to work; 25% are self-employed, in comparison with 10% of the total population. Five percent of the geriatric population—nearly 1 million individuals—are victimized by abuse or neglect. The U.S. Bureau of the Census estimates that 1 million Americans will be 100 years of age or older by the year 2050 and that nearly 2 million will be that age by the year 2080.

Falls are the leading cause of death from injury in individuals 65 years of age and older. Two thirds of reported injury-related deaths in patients 85 years of age and older are caused by falls. Falls are a leading cause of traumatic brain injuries. Approximately 3% to 5% of falls in older adults cause fractures. On the basis of the 2000 census, this translates to 360,000 to 480,000 fall-related fractures each year. Of all fall-related fractures, hip fractures cause the greatest number of deaths and lead to the most severe health problems and reductions in quality of life. In 1991, Medicare costs for hip fractures were estimated to be $2.9 billion. A fear of falling is also common; 50% to 60% of all patients older than 65 years of age have this fear.

Structure and Physiologic Characteristics

This section covers some of the anatomic and physiologic changes attributed to aging, as well as some of the physical findings that result.

Skin

There is atrophy of the epidermis, hair follicles, and sweat glands, which results in thinning skin. The skin becomes fragile and discolored. Wrinkling and dryness result from reduced skin turgor. In addition, the nails become thin and brittle, with marked ridging. There is decreased vascularity of the dermis, which contributes to prolonged healing time. There are common pigmentary changes, such as the development of senile lentigines, or “liver spots.” These brown macules are commonly found on the backs of the hands, forearms, and face. They are caused by localized mild epidermal hyperplasia, in association with increased numbers of melanocytes and increased melanin production. Figure 22-1 shows senile lentigines on the hand of an 87-year-old woman.

Figure 22–1 Senile lentigines in an 87-year-old woman. Notice the well-demarcated, brownish-black macules.

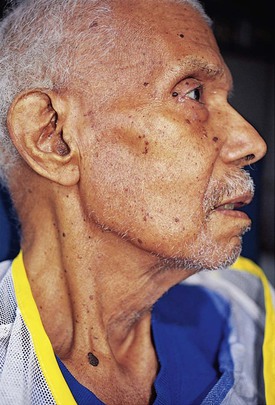

Another common skin change is senile (solar) keratosis, which is a well-defined, raised papule or plaque of epidermal hyperkeratosis. The surface scale varies in color from yellow to brown. These lesions are common on the face, neck, trunk, and hands. Figure 22-2 shows several senile keratoses on an 82-year-old man.

There is commonly a degeneration of the elastic fibers and collagen of the skin, resulting in a loss of elasticity and the development of senile purpura. These purple macules, commonly seen on the backs of the hands or on the forearms, result from blood that has extravasated through capillaries that have lost their elastic support. Figure 22-3 shows senile purpura on the forearm of a 90-year-old woman.

Figure 22–3 Senile purpura on the forearm of a 90-year-old woman. Note the red macules and the loss of turgidity of the skin.

Sebaceous gland hyperplasia, especially on the forehead and nose, is common. These yellowish glands range in size from 1 to 3 mm and have a central pore. It is important to differentiate these benign lesions from basal cell carcinomas.

Hair loses its pigment, which commonly results in “graying” of the hair. With the reduction in the number of hair follicles, there is hair loss all over the body: head, axilla, pubic area, and extremities. With the reduction in estrogens, an increase in hair may actually develop in many older women, especially on the chin and upper lip. Chin hairs on a 79-year-old woman are shown in Figure 22-4.

As a result of the reduction in subcutaneous tissue, there is less insulation and less padding over bony surfaces. This predisposes older people to hypothermia and the development of pressure sores, or decubitus ulcers. Figure 22-5 shows a pressure sore that developed on an 85-year-old man within 1 week. The man had been seen 1 week earlier when a small, intact erythematous area was noticed over his sacral area. He was brought back to the emergency department 7 days later with the decubitus ulcer seen in the figure. The ulceration eroded through the skin and muscle, into the sacrum, and into the bowel, with the development of a rectovesicular fistula.

Eyes

As a result of a reduction of orbital fat, the eyes appear sunken. Laxity of the eyelids, or senile ptosis, often develops. Entropion (see Fig. 7-19) or ectropion (see Fig. 7-20) may develop, caused by the lower eyelid’s falling inward or falling away, respectively. There may also be a clogging of the lacrimal duct, resulting in epiphora, or tearing. Fatty deposits in the cornea may produce an arcus senilis, seen in Figures 7-57 and 7-58. Inadequate production of mucous tears by the conjunctiva may predispose persons to corneal ulcers, exposure keratitis, or dry eye syndrome (see Chapter 7, The Eye).

An accumulation of yellow pigment in the lens alters color perception. A loss of elasticity in the lens results in presbyopia. Nuclear sclerosis of the lens develops into cataract formation. Patients experience a decrease in visual acuity and commonly complain of sensitivity to glare from interior lights, sunlight, or reflection from floors.

Degenerative changes in the iris, vitreous humor, and retina may impair visual acuity, reduce the fields of vision, and lead to the development of floaters (muscae volitantes). Senile macular degeneration (see Figs. 7-125 to 7-127) and retinal hemorrhages are other medically significant causes of decreases in visual acuity.

Ears

Degeneration of the organ of Corti may result in presbycusis, an impaired sensitivity to high-frequency tones. Patients experience a slowly progressive hearing loss with a consistent pattern of pure tone loss. Otosclerosis may produce conductive deafness, as does the excessive cerumen accumulation so commonly seen in older individuals. A degeneration of the hair cells in the semicircular canals may produce vertigo.

Nose and Throat

Atrophic changes occur in the mucosa of the nose and throat. Taste and especially smell may be altered, particularly in institutionalized individuals. A decrease in mucous production predisposes older patients to upper respiratory infections. A loss of elasticity in the laryngeal muscles may produce tremulousness and high pitch of the voice.

Mouth

Loss of teeth from dental caries or periodontal disease is common. Gingival recession may produce problems with dentures and a malalignment of bite. Atrophic changes in the salivary glands cause dryness of the mouth, known as xerostomia, a common complaint among older adults.

Lungs

A loss of elasticity in the pulmonary septa and atrophy of the alveoli cause a coalescence of the alveoli, with a reduction in vital capacity and oxygen diffusion. There are decreases in forced vital capacity and expiratory flow rate. A degeneration of bronchial epithelium and mucous glands increases the susceptibility to infections. Skeletal changes also contribute to a decrease in vital capacity.

Cardiovascular System

A loss of elasticity of the aorta may cause aortic dilation. The semilunar and atrioventricular valves may degenerate and become regurgitant. Alternatively, these valves may become sclerotic, which causes stenosis of the valves. Degeneration or calcification of the conducting system may cause heart block or arrhythmias.

Noncompliance of the peripheral arteries may cause hypertension with a widened pulse pressure. Systolic blood pressure rises progressively with age, whereas diastolic pressure levels off in the sixth decade of life; these developments lead to an increased prevalence of isolated systolic hypertension. Coronary atherosclerosis may produce angina, myocardial infarction, or nonspecific symptoms such as confusion or tiredness.

There are also decreases in plasma volume, ventricular filling time, and baroreflex sensitivity.

Breasts

The amount of glandular tissue decreases, and the tissue is replaced by fatty deposits. As a result of a loss of elastic tissue, the breasts become pendulous, and the ducts may be more palpable.

In men, gynecomastia may result from a change in the metabolism of sex hormones by the liver (see Fig. 13-21).

Gastrointestinal System

Atrophy of the gastrointestinal mucosa occurs with a reduction in the number of stomach and intestinal glands, causing alterations in secretion, motility, and absorption. Changes in elastic tissue and colonic pressures may result in diverticulosis, which can lead to diverticulitis. Pancreatic acinar atrophy is common, as are decreases in hepatic mass, hepatic blood flow, and microsomal enzyme activity. These decreases result in an increased half-life of lipid-soluble drugs.

Genitourinary System

There is a decrease in the number of glomeruli and a thickening of the basement membrane in Bowman’s capsule, resulting in a reduction in renal function. Degenerative changes occur in the renal tubules, which themselves are reduced in number. Renal blood flow is reduced to half by 75 years of age. Vascular changes may also contribute to a reduced glomerular filtration rate.

In men, prostatic atrophy or prostatic hypertrophy develops. Benign prostatic hypertrophy is present in 80% of all men older than 80 years. The penis decreases in size, and the testicles hang lower in the scrotum.

In postmenopausal women, the reduction in estrogen is associated with an increase in susceptibility to osteoporosis. The labia and clitoris are reduced in size, and the vaginal mucosa becomes thin and dry. The uterus and ovaries also decrease in size.

As discussed previously, pubic hair decreases in amount and becomes gray.

Endocrine System

There is decreased metabolism of thyroxine and decreased conversion of thyroxine to triiodothyronine. Because of a reduction in pancreatic beta cell secretion, hyperglycemia may result. The hypothalamus and the pituitary gland secrete reduced amounts of hormones. An increase in the secretion of antidiuretic hormone and atrial natriuretic hormone may alter fluid balance. There are also increased levels of norepinephrine.

Musculoskeletal System

There is general atrophy of muscles, causing a decline in strength. Muscle wasting is seen most commonly in the distal extremities, especially in the dorsal interosseous muscles.

Osteoclastic activity is greater than osteoblastic activity. An enlargement of the cancellous bone spaces and a thinning of the trabeculae result in osteoporosis. Kyphosis and a loss of height are common (see Fig. 10-6). Degenerative changes and a loss of elastic tissue occur in joints, ligaments, and tendons. This frequently results in joint stiffness. Degenerative changes in bone may result in bone cysts and erosions, making these bones prone to fracture. Osteoarthritis is common. Thinning of cartilage and synovial thickening produce joint stiffness and pain. Range of motion is also reduced, perhaps because of pain. Figure 17-58 shows Heberden’s and Bouchard’s nodes in an 86-year-old woman with osteoarthritis.

Nervous System

Changes in brain function may adversely affect memory and intelligence, although other skills such as language and sustained attention may remain. Significant variability exists among individuals, and many older individuals continue to perform at levels comparable with or exceeding those of much younger people.

Brain weight is frequently reduced 5% to 7% as a result of atrophy of selected areas. There is a decrease in blood flow to the brain by 10% to 15%. Vascular changes of atherosclerosis can result in multiple infarcts or transient ischemic attacks.

Reflexes are commonly reduced; the gag reflex is frequently absent. The Achilles tendon reflex is often symmetrically reduced or absent. Primitive reflexes, such as snout or palmomental, may be present in normal older adults.

Hematopoietic System

There is an increase in the amount of marrow fat and a decrease in the amount of active bone marrow.

Immune System

There is a decreased number of newly formed T lymphocytes and a reduced capability of T lymphocytes to proliferate in response to mitogens or antigens. Humoral immunity is impaired, and suppressor T lymphocytes are decreased in number.

Basic Principles of Geriatric Medicine

Whereas in the younger population the goal of medicine is to cure, the ultimate goal in the geriatric population is to preserve the patient’s quality of life. The health care professional must strive to maintain function and relieve the symptoms that can be relieved. This often involves moving from a doctor-patient relationship alone to a doctor-family or doctor-caregiver relationship. In the event of terminal illness, you should ensure as little mental and physical distress as possible and provide appropriate emotional support to the patient and family. There are a few basic principles of geriatric medicine.

First, there is an altered manifestation of disease. The actual symptom may not be a symptom of the organ system involved with the disease. For example, if a person in his or her 50s were to have a heart attack, the individual, unless diabetic, would usually suffer from chest pain. This is not the case in the geriatric age group. It is well documented that 70% of nondiabetic individuals older than 70 years of age do not have chest pain with a myocardial infarction. Such patients may present instead with breathlessness, falling, confusion, or palpitations.

Another illustration of this alteration in symptoms is the geriatric patient with diabetes mellitus. Ordinarily, because of lack of insulin, younger patients become acidotic and ketotic, with a smell of ketones on their breath. They may also exhibit shallow, rapid respirations. Older patients with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus may not become ketotic and acidotic. Instead, the syndrome of hyperosmolar, nonketotic coma may ensue. These patients, who do not have the smell of ketones on their breath and are not acidotic, are hyperosmolar and may have serum glucose levels in excess of 600 to 700 mg/dL. They may even present in coma.

A third example is a patient with hyperthyroidism. A geriatric patient with hyperthyroidism might not present with the tachycardia, sweats, or anxiety states that are seen in younger individuals with increased thyroid activity. The geriatric patient may instead appear depressed and apathetic.

An older patient with acute appendicitis might not suffer from abdominal pain, and an older patient with pneumonia might not have shortness of breath; confusion may be the only symptom.

A second principle in geriatric medicine is the nonspecific manifestation of disease. When an older person becomes ill, a family member commonly reports that the patient “just hasn’t gotten out of bed.” The patient may go to bed and stay there. The patient may not want to eat and may have only nonspecific complaints.

A fourth principle is the recognition that multiple pathologic conditions may be present in a geriatric patient. Such a patient may have been given multiple medications or therapies. One medicine may have deleterious effects on a patient if some other condition exists. Of course, this can occur with any patient, but it is more likely to occur in older patients who probably have several pathologic conditions.

A fifth principle is polypharmacy, which is defined as the administration of three or more medicines. It is critical that the interviewer see and know about all the medications being taken by the patient. Instruct the patient or family to bring in all medications, both prescription and nonprescription, and ask the patient how he or she is taking them. There is commonly a significant discrepancy between the written prescription and the dosage that the patient actually takes.

Americans older than 65 years of age use approximately 25% of all prescription medications consumed in the United States, and at any one time, the average geriatric patient uses 4.5 prescription medications. The average nursing home resident consumes the most medications, averaging 8 medications at any one time. The use of mood-altering drugs is common in the geriatric population. Approximately 7% of nursing home residents are taking 3 or more psychoactive drugs.

Finally, what is the patient’s chief complaint? This is sometimes referred to as “the myth of the chief complaint.” Many geriatric patients do not have a single complaint. There may be several problems related to their many conditions. In fact, as already discussed, if a chief complaint is given, it may bear no relationship to the organ system involved. Be careful in the evaluation of the chief complaint when dealing with older patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree