The Nursing Workforce

Mary Lou Brunell and Angela Ross

“If we want affordable, patient-centered health care in this country, then we have to make a renewed commitment to nurses, who carry out such important work.”

—Representative Tom Latham, R-Iowa, March 12, 2009

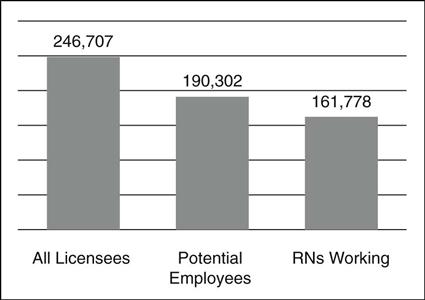

The supply of nurses in the United States is made up of all licensed practical/vocational nurses (LPNs), registered nurses (RNs), and advanced registered nurse practitioners (ARNPs). Those with active licenses that are clear (without disciplinary or other limitation) are eligible for employment and represent the potential nurse employment pool. The actual nursing workforce is composed of those working in the practice of nursing or those whose job requires a license. To demonstrate the significance of these distinctions, Figure 49-1 illustrates the breakdown of licensed RNs, including ARNPs, in Florida, compared to those that define Florida’s potential nursing workforce, and then to those that are actually working (Florida Center for Nursing [FCN], 2009).

Successful planning requires knowing the real workforce supply numbers. As shown in Figure 49-1, there is a difference of nearly 85,000 RNs (34.4%). Using the wrong base number could make it appear that a shortage does not exist—on paper—when reality says otherwise. Forecasting models project demand based on the current supply of nurses and the reported need (employment) for nurses. Demand exists when the supply does not meet the need. If there is a need for 200,000 nurses, a supply of 246,707 indicates no demand, while a supply of 161,778 implies a demand for nearly 40,000 nurses.

Characteristics of the Workforce

The U.S. nursing workforce is the largest potential nursing workforce in the world and is still predominately female and White/Non-Hispanic, with only 6.6% of surveyed respondents reporting as male and 16.8% reporting as Non-White/Hispanic (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], Health Resources and Services Administration [HRSA], 2010). These nurses are the frontline providers of care for many health care consumers.

In 2006, the USDHHS HRSA projected a shortage of 1 million full-time-equivalent (FTE) RNs by 2020—with RNs working full-time counted as 1 FTE and RNs working part-time counted as one-half of an FTE (USDHHS, Bureau of Health Professions, 2004). A nursing shortage exists because demand, or need, exceeds the supply. Demand is expected to increase more rapidly than the supply as the Baby Boomer cohort of the U.S. population reaches retirement age. In 2007, the U.S. entered a severe economic recession. Buerhaus, Auerbach, & Staiger (2009) evaluated the impact of this economic recession on the projected nursing shortage. The authors found that in 2007 and 2008 combined, hospital RN employment increased by 243,000 FTE RNs—the largest 2-year increase in their 30-year dataset. In addition to representing increased education capacity over the previous several years, this influx is probably attributable to delayed retirements by older nurses, increases in hours worked, and re-entry of younger nurses to the workforce following spouse layoffs or reduction in work. Thus, even with record-setting growth in the nursing workforce, this report states that the country is still expected to see a shortage of 260,000 FTE RNs by 2025.

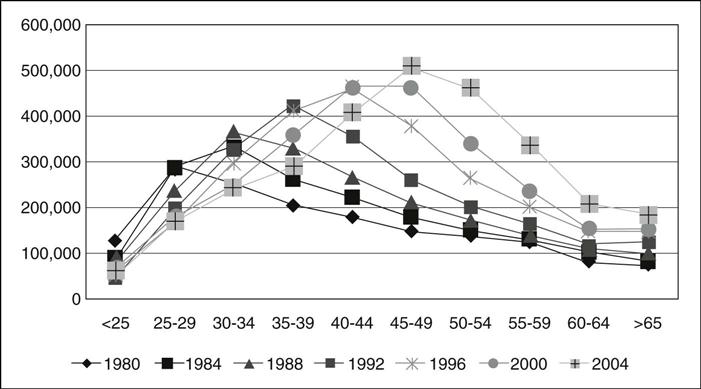

It is no surprise that the current nursing shortage is not its first. During the 1980s, the country faced two marked nursing labor shortages, caused primarily by wage controls and cost-cutting approaches. They were essentially resolved through wage increases and increased funding for nursing education. What makes the current shortage different is that it isn’t driven by the cyclic nature of the economy. A significant portion of the nursing workforce is approaching retirement age, and there are not enough younger nurses entering the profession to replace them. The average age of the RN population was 46.8 in 2004. Figure 49-2 details how the average age of nurses has climbed upward on every HRSA survey since 1980 (USDHHS, 2006).

This exodus of experienced nurses has grave implications for patients, nurses, and employers. Studies have corroborated the intuitive idea that when nurses are understaffed, patient safety suffers and medical errors increase (Kane, Shamliyan, Mueller, Duval, & Wilt, 2007; Mark Harless, McCue, & Xu, 2004; Aiken, Clarke, Sloane, Sochalski, & Silber, 2002; Needleman, Buerhaus, Mattke, Stewart, & Zelevinsky, 2002). Understaffing also leads to nurse burnout (Aiken et al., 2002), which, of course, causes increased turnover and more nurse burnout. The demand for nurses is expected to dramatically increase as consumers are living longer with more chronic diseases; a significant portion of the population is approaching retirement age, creating increased need for health care services. As patients, these consumers will require a level of care that is best provided by an appropriate balance of nurses—those with years of hands-on experience and knowledge along with new nurses fresh from the education system.

Recent estimates put the cost of nurse turnover at up to 200% of a nurse’s annual salary (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation [RWJF], 2006; Hayes et al., 2006; Jones, 2004, 2005; Waldman, Kelly, Arora, & Smith, 2004). The costs associated with turnover and understaffing have a powerful impact on the economy. In an article analyzing the economic value of RNs, Dall and colleagues (2009) found significant economic value when even a single RN was added to an understaffed unit. The authors calculated the costs of patient mortality due to understaffing and evaluated the benefits of adding 133,000 FTE RNs to the acute care hospital workforce—the number needed to improve staffing at hospitals with low to medium staffing levels. Increasing these nurses could save 5900 patient lives each year, with a productivity value of $1.3 billion annually. They also found that this increase in workforce would reduce hospital stays by 3.6 million days and thus generate additional productivity value of $231 million annually and $6.1 billion in annual medical savings. In Florida alone, the Florida Center for Nursing found that the cost of turnover for LPNs and RNs exceeded $1.6 billion in fiscal year 2006-2007 (FCN, 2008a).

This research makes a compelling case to address nurse supply needs by not only expanding the workforce, but also by retaining current nurses. Although continuing to expand education capacity and produce new nurses is important, more needs to be done. As with the nursing workforce in general, the educator workforce is also aging and a mass wave of faculty retirements is anticipated within the next decade. There is already a faculty shortage, making it impossible for nursing education programs to accept the number of students needed to meet the demand. More than 49,000 qualified applicants were turned away from baccalaureate and graduate nursing programs in 2008 due to limited funding for faculty, lack of clinical sites, and lack of qualified faculty applicants (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], 2009a). Even if education capacity could be expanded to meet demand, there will still be a lapse before an adequately experienced workforce is operational. Policy initiatives must take a multipronged approach by focusing on expanding both the general nursing and faculty workforce, increasing diversity, and retaining workers.

Expanding the Workforce

Nursing education programs must be expanded to facilitate growth in the nursing workforce. Successful expansion should be measured—not just by increased admissions, but also by increased graduations and successful passage of the National Council Licensure Examination for Registered Nurses (NCLEX). Lack of funding to hire additional faculty members and lack of qualified faculty applicants are consistently identified as reasons why programs turn away qualified applicants (AACN, 2009a). Increased funding for graduate education is an essential first step toward increasing capacity. Funding for graduate education could help expand the faculty pipeline while also expanding the pool of candidates for other hard-to-fill nursing positions. Through HRSA, the federal government has a variety of grant programs that offer loan repayment for nurses (USDHHS, 2009).

Another key reason for lack of faculty applicants is the wide discrepancy between clinical and educational salaries. Nurses can often earn significantly more in clinical practice than in teaching. Kaufman (2007) suggests that this salary difference may be a chief reason for the faculty shortage. Funding aimed at increasing salaries for nurse faculty in entry-level programs (associate and baccalaureate) would have considerable impact on reducing the faculty shortage where doctoral education may not be provided for faculty positions. Many employers partner with local colleges to develop faculty sharing programs; employers pay for salary and benefits and then donate 50% to 100% of the nurse’s time to the school. These programs have been quite successful, enabling educational institutions to expand admissions while providing faculty who are familiar with the clinical sites and policies. Employers may also offer tuition reimbursement for nurses seeking an advanced degree; this not only serves as a retention strategy for the employer, but may expand the pool of potential nurse educators. Private donations are another source of additional funding for educational programs.

Strategic utilization of scarce resources is a critical component of effectively expanding education capacity. Lack of access to clinical sites ranks as a barrier to expansion. As a result, simulation technology is being used as a highly effective method for hands-on experience with a wide range of clinical scenarios. Though the cost of simulation technology is still high, collaboration among educational programs may be the most beneficial. Some examples of collaboration include the following:

• In Colorado, the state’s nursing workforce center developed the Colorado Work, Education, and Lifelong Learning Simulation (WELLS) Center (www.wellssimulationcenter.org). This single facility provides state-of-the-art patient simulation tools and curricula to educate nursing students, faculty, and practicing nurses and physicians throughout the state. Not only does the simulation center provide clinical space for students, it also serves as a resource for continuing education for faculty members and clinical practitioners.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree