Chapter 17

The Musculoskeletal System1

The hand of the Lord was upon me … and set me down in the midst of the valley which was full of bones … behold, there were very many in the open valley; and, lo, they were very dry. … Thus saith the Lord God unto these bones: Behold, I will cause breath to enter into you, and ye shall live. And I will lay sinews upon you, and will bring up flesh upon you, and cover with skin, and put breath in you, and ye shall live … there was a noise, and behold a commotion, and the bones came together, bone to bone … and skin covered them … and the breath came into them, and they lived, and stood up upon their feet.

Ezekiel 37:1–10

General Considerations

Diseases of the musculoskeletal system rank first among disease conditions that alter the quality of life. This is related to limitation of activity, disability, and impairment. Musculoskeletal disorders are associated with high costs to employers such as absenteeism; lost productivity; and increased health care, disability, and worker’s compensation costs. Musculoskeletal disorders are more severe than the average nonfatal injury or illness (e.g., hearing loss, occupational skin diseases such as dermatitis, eczema, or rash). In the United States, one of every four persons suffers from some sort of musculoskeletal disorder. Here are the facts:

• The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported 372,683 back injury cases involving days away from work.

• Persons who are limited in their work by arthritis are said to have arthritis-attributable work limitations. These limitations affect 1 in 20 working-age adults (aged 18–64) in the United States and 1 in 3 working-age adults with self-reported, doctor-diagnosed arthritis.

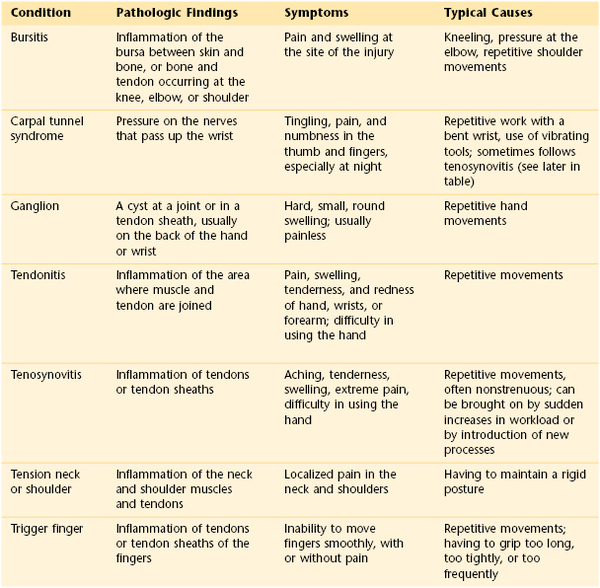

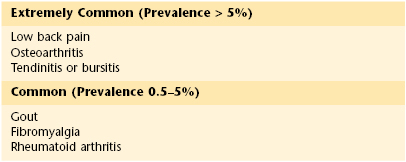

Table 17-1 lists some of the more common musculoskeletal disorders.

Table 17–1

Common Musculoskeletal Disorders

Adapted from http://www.afscme3090.org/ergo/pdf/common_musculoskeletal_disorders.pdf.

Diseases of the musculoskeletal system are divided into two categories: systemic and local. Patients with systemic disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, or polymyositis, may appear chronically ill, with generalized weakness, pain, and episodic stiffness of the joints. Patients with local disease are basically healthy individuals who suffer restriction of motion and pain from a single area. Included in this group are patients suffering from back pain, tennis elbow, arthritis, or bursitis. Although these patients may have only local symptoms, their disability can greatly limit their work capacity, and the disease can have a severe effect on their quality of life.

Diseases of the musculoskeletal system rank first in cost to workers’ compensation insurance carriers. Nearly 100,000 workers receive disability payments annually, with a total cost to the carriers of more than $200 billion annually.

Although not usually fatal disorders, musculoskeletal conditions affect the quality of life. Studies indicate that backache is experienced by more than 80% of all Americans at some time in their lives. Patients with backache for longer than 6 months constitute a large portion of permanently disabled individuals. More than 50% of these patients never return to work. More than 25 million Americans suffer from arthritis that necessitates medical attention. Arthritis ranks second to cardiac disease as a cause of limitation of activity. Table 17-2 lists the most common musculoskeletal disorders in adults aged 45 years or older with the disease prevalence in the United States.

Table 17–2

The Most Common Musculoskeletal Disorders in Adults Aged 45 Years and Older:

Prevalence in Adult Populations in the United States

In the United States at least 10% of the population experiences a bone fracture, dislocation, or sprain annually. Each year more than 1.2 million fractures are sustained by women older than 50 years. There are more than 200,000 hip fractures annually, and these are associated with prolonged disability. Osteoporosis2 is the most common musculoskeletal disorder in the world and is second only to arthritis as a leading cause of morbidity in the geriatric population. Postmenopausal osteoporosis and age-related osteoporosis increase the risk of fractures in the older population. There are more than 40 million women in the United States older than 50 years, and more than 50% of them have evidence of spinal osteoporosis. Almost 90% of women older than 75 years have significant radiographic evidence of osteoporosis.

The high prevalence of musculoskeletal disease in older adult patients who require assistance has a significant effect on the American economy. The annual cost of nursing home care for patients with musculoskeletal disease is almost $75 billion. More than 10 million individuals in the United States have some form of inflammatory arthritis, the most prevalent being rheumatoid arthritis. It is estimated that more than 7 million patients have this form of arthritis.

Musculoskeletal problems have the most significant financial effect on the aged population. More than $1 billion is spent annually by Medicare for hospitalization of patients with these conditions. This represents 20% of all Medicare payments.

Structure and Physiology

The principal functions of the musculoskeletal system are to support and protect the body and to bring about movement of the extremities for locomotion and the performance of tasks.

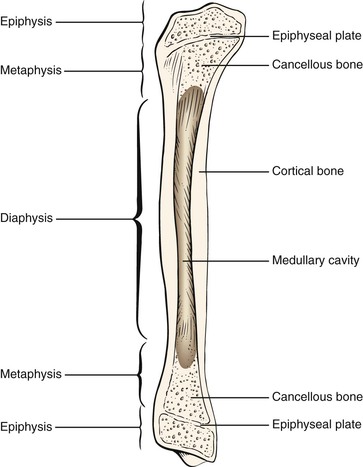

Bone is composed of an organic matrix that consists of collagen fibers embedded in a cementing gel made up of calcium and phosphate. Bone is an actively changing tissue constantly undergoing remodeling while reappropriating its mineral stores and matrix according to mechanical stresses. Normal bone is composed of collagen fibers aligned parallel to the tension stresses to which the bone is exposed. The long bones in adults are composed of tubes of cortical, or compact, bone surrounding a medullary cavity of cancellous, or spongy, bone. Cortical bone exists in areas where support is necessary, whereas cancellous bone is found in areas where hematopoiesis and bone formation occur. In cortical bone, the bone cells, or osteocytes, are enclosed in lacunae, which are spaces in the sheets of bone tissue called lamellae. Several lamellae are arranged concentrically around a vascular channel and are termed a haversian canal. In cancellous bone, the lamellae are not arranged in haversian systems but are organized into a spongy network called trabeculae. These trabeculae align along lines of stress.

The ends of the long bones, called epiphyses, are expanded near the articular surfaces and are composed of spongy bone. The shaft of the long bone, the diaphysis, is covered with a layer of periosteum. The inner cavity of the long bone is lined with endosteum and is filled with marrow.

For a time, a layer of cartilage exists between the diaphysis and the epiphysis. This cartilage is known as the growth plate or epiphyseal plate. The purpose of the growth plate is to determine the longitudinal growth of the bone. The parts of a long bone are illustrated in Figure 17-1.

Cells in the periosteum can develop into osteoblasts, which lay down new bone, or into osteoclasts, which resorb bone. Trauma, infection, and tumors stimulate the development of osteoblasts. Osteoblasts secrete the matrix that is refashioned into lamellae and arranged to endure the mechanical stresses to which the bone is subjected.

Skeletal muscle is an organ, the contraction of which produces movement.

Ligaments attach bone to bone, and tendons attach muscle to bone. Both are dense connective tissues that offer great resistance to pulling forces.

Cartilage is a type of connective tissue with great resilience. It plays an important role in joint function and in determining bone length.

The basic functional unit of the musculoskeletal system is the joint. A joint is a union of two or more bones. There are several types of joints in the body:

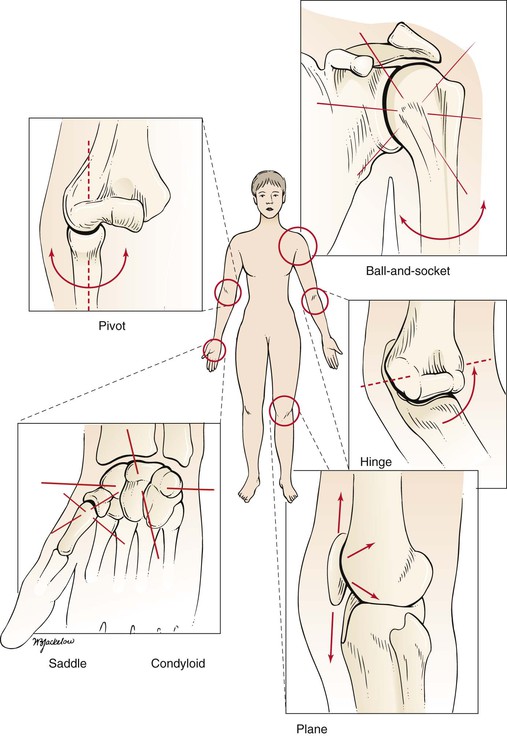

Immovable joints are fixed as a result of fibrous tissue banding. Examples of this type of joint are the sutures of the skull. Slightly movable joints are termed symphyses. In this type of joint, fibrocartilage joins the articulating bones. The pubic symphysis is an example of a slightly movable joint. The most common type of joint is the movable joint. The body has many different types of movable joints, also known as synovial joints. In synovial joints, the bone structures come in contact with each other and are covered with hyaline articular cartilage. A capsule surrounds the joint by attaching to the bones on either side of the joint. Within the capsule is a small amount of synovial fluid, which plays a role in joint lubrication and nourishment of the articular cartilage. Synovial joints are classified according to the type of movement their structure permits. The classifications are as follows:

A hinge joint permits movement in only one axis: namely, flexion or extension. The axis is transverse. An example of a hinge joint is the elbow. A pivot joint permits rotation in one axis. The axis is longitudinal along the shaft of the bone. One bone moves around a central axis without any displacement from that axis. An example of a pivot joint is the proximal radioulnar joint. A condyloid joint permits movement in two axes. The articular surfaces are oval; thus these joints have been described as “egg-in-spoon” joints. One axis is the long diameter of the oval, and the other axis is the short diameter of the oval. The wrist joint is an example of a condyloid joint. A saddle joint is also a biaxial joint. The articular surfaces are saddle-shaped, with movements similar to those of a condyloid joint. The carpometacarpal joint of the thumb is an example of a saddle joint. The ball-and-socket joint is an example of a polyaxial joint; motion is possible in many axes. In a ball-and-socket joint, the articular surfaces are reciprocal segments of a sphere. The hip and shoulder joints are examples of ball-and-socket joints. A plane joint is also a polyaxial joint. In the plane joint, the articular surfaces are flat, and one bone merely rides over the other in many directions. The patellofemoral joint is an example of a plane joint. These different types of movable joints are shown in Figure 17-2.

The stability of a joint depends on the following:

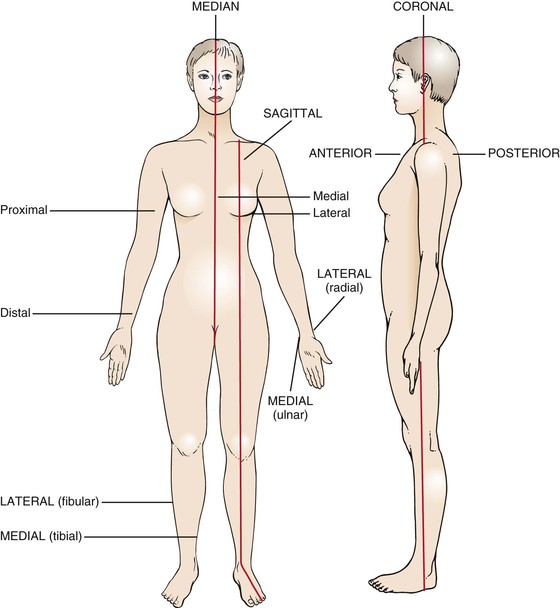

It is necessary to be familiar with certain anatomic terms that refer to position (Table 17-3). The median plane bisects the body into right and left halves. A plane parallel to the median plane is a sagittal plane. The terms medial and lateral are used in reference to the sagittal plane. A position closer to the median plane is medial; farther from the median plane, it is lateral. In the upper limb, the term ulnar is often used to denote medial, and radial to denote lateral. In the lower limb, tibial is used to denote medial, and peroneal or fibular denotes lateral. These anatomic terms are illustrated in Figure 17-3.

Table 17–3

Anatomic Terms for the Upper and Lower Limb

| Limb | Medial | Lateral |

| Upper | Ulnar | Radial |

| Lower | Tibial | Peroneal fibular |

The front of the body is the anterior, or ventral, surface, and the back of the body is the posterior, or dorsal, side. The palmar, or volar, aspect of the hand is the anterior surface. The dorsal aspect of the foot faces upward, and the plantar aspect is the sole. Proximal refers to the part of an extremity that is closest to its root; distal refers to the part farthest from the root.

The most important terms relating to deformities of the bone structure are valgus and varus. In a valgus deformity, the distal portion of the bone is displaced away from the midline, and angulation is toward the midline. In a varus deformity, the distal portion of the extremity is displaced toward the midline, and angulation is away from the midline. The name of the deformity is determined by the joint involved. A valgus deformity of the knees, knock-knee, is termed genu valgum. A varus deformity of the knee, bowleg, is termed genu varum.

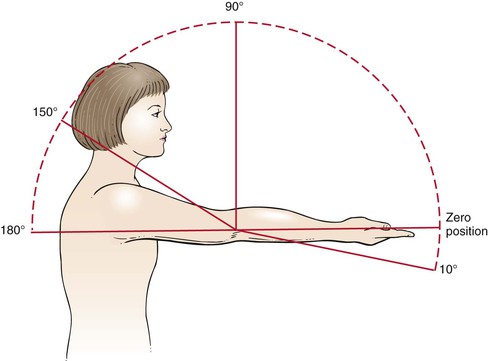

In the evaluation of a joint, assess the range of motion. Each joint has a characteristic range of motion that can be measured passively and actively. Passive range of motion is the motion elicited when the examiner moves the patient’s body. Active range of motion is the motion the patient performs as a result of moving the musculature. The passive range of motion usually equals the active range of motion except in cases of paralyzed muscles or ruptured tendons. The range of motion of individual joints is discussed later in this chapter. Joint motion is measured in degrees of a circle, with the joint at the center. If a limb is extended with the bones in a straight line, the joint is at zero position. The zero position is the neutral position of the joint. As the joint is flexed, the angle increases. The concept of range of motion is illustrated in Figure 17-4.

The six basic types of joint motion are as follows:

The definitions of these motions and the joints at which they occur are summarized in Table 17-4.

Table 17–4

Joint Motion

| Motion | Definition | Example |

| Flexion | Motion away from the zero position | Most joints |

| Extension | Return motion to the position* | Most joints |

| Dorsiflexion | Movement in the direction of the dorsal surface | Ankle, toes, wrist, fingers |

| Plantar (or palmar) flexion | Movement in the direction of the plantar (or palmar) surface | Ankle, toes, wrist, fingers |

| Adduction | Movement toward the midline† | Shoulder, hip, metacarpophalangeal, metatarsophalangeal joints |

| Abduction | Movement away from the midline | Shoulder, hip, metacarpophalangeal, metatarsophalangeal joints |

| Inversion | Turning of the plantar surface of the foot inward | Subtalar and midtarsal joints of the foot |

| Eversion | Turning of the plantar surface of the foot outward | Subtalar and midtarsal joints of the foot |

| Internal rotation | Turning of the anterior surface of a limb inward | Shoulder, hip |

| External rotation | Turning of the anterior surface of a limb outward | Shoulder, hip |

| Pronation | Rotation so that the palmar surface of the hand is directed downward | Elbow, wrist |

| Supination | Rotation so that the palmar surface of the hand is directed upward | Elbow, wrist |

* Extension that goes beyond the zero position is called hyperextension.

† In the hand or foot, the midline is an imaginary line through the middle finger or middle toe, respectively.

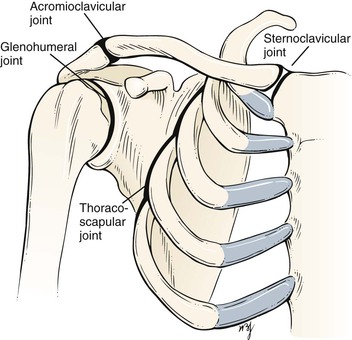

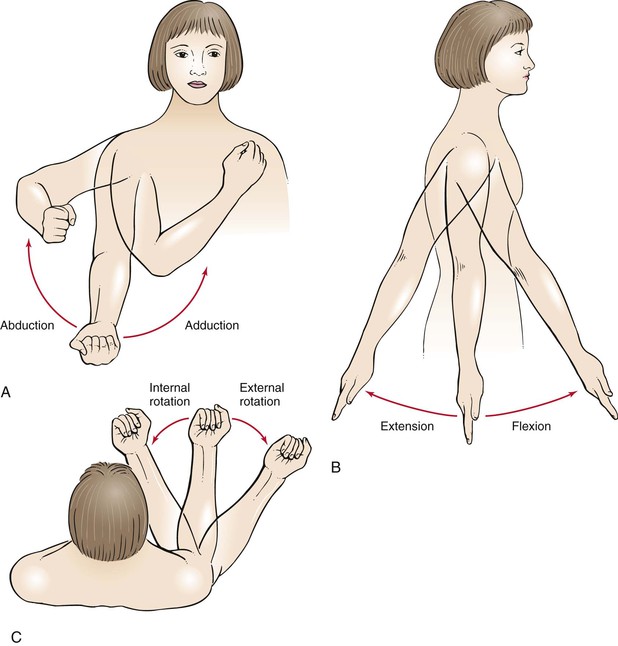

The anatomy of the shoulder joint is illustrated in Figure 17-5. The joint movements at the shoulder are abduction and adduction, flexion and extension, and internal and external rotation. These motions are illustrated in Figure 17-6.

Figure 17–6 Range of motion at the shoulder. A, Abduction and adduction. B, Flexion and extension. C, Internal and external rotation.

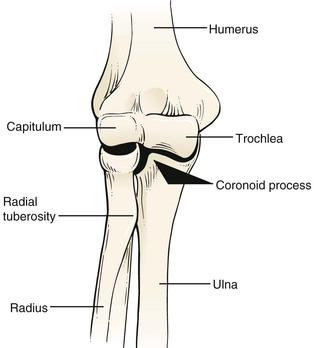

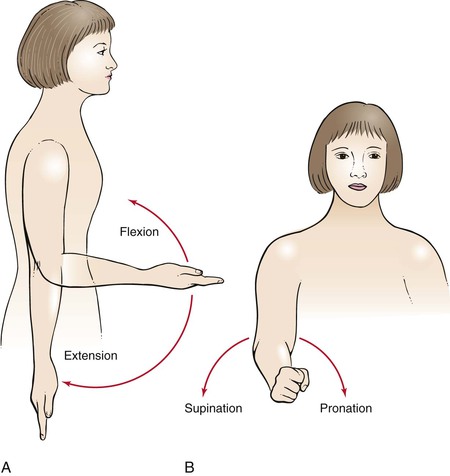

The anatomy of the elbow joint is shown in Figure 17-7. The joint movements at the elbow are flexion and extension and supination and pronation. These motions are illustrated in Figure 17-8.

Figure 17–8 Range of motion at the elbow joint. A, Flexion and extension. B, Supination and pronation.

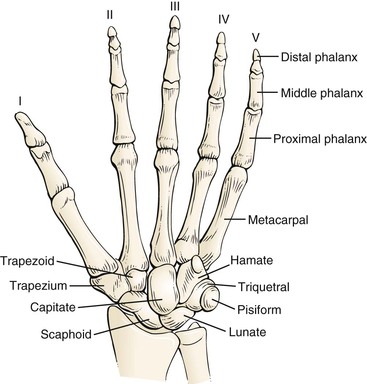

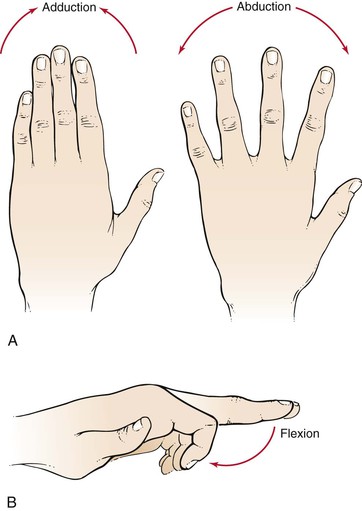

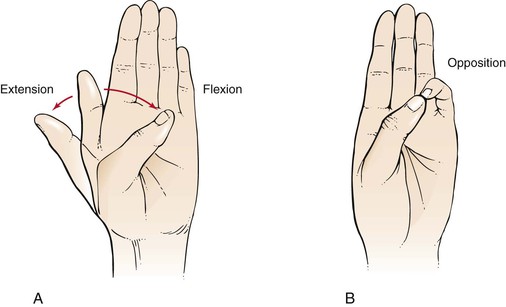

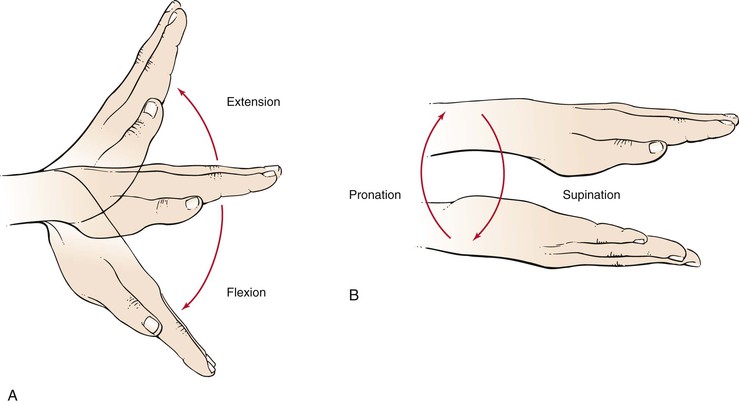

The anatomy of the wrist and fingers is illustrated in Figure 17-9. The joint movements at the wrist are dorsiflexion (or extension) and palmar flexion and supination and pronation. These motions are illustrated in Figure 17-10. The joint movements at the fingers are abduction and adduction and flexion. These motions are illustrated in Figure 17-11. The joint movements of the thumb are flexion and extension and opposition. These motions are illustrated in Figure 17-12.

Figure 17–10 Range of motion at the wrist joint. A, Dorsiflexion (extension) and palmar flexion. B, Supination and pronation.

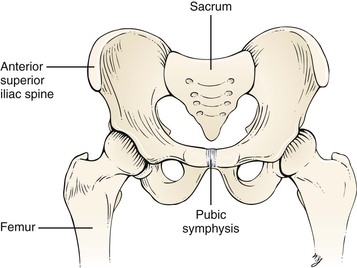

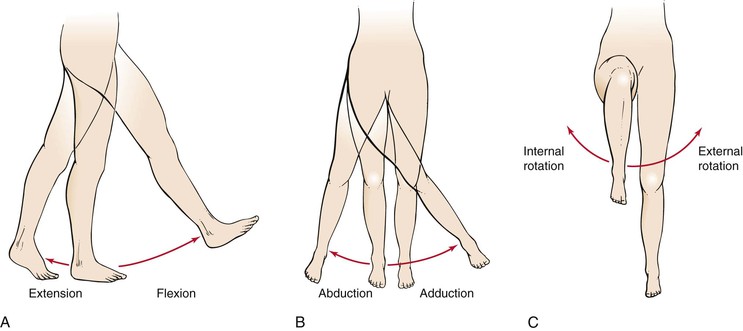

The anatomy of the hip is illustrated in Figure 17-13. The joint movements at the hip are flexion and extension, abduction and adduction, and internal and external rotation. These motions are illustrated in Figure 17-14.

Figure 17–14 Range of motion at the hip joint. A, Flexion and extension. B, Abduction and adduction. C, Internal and external rotation.

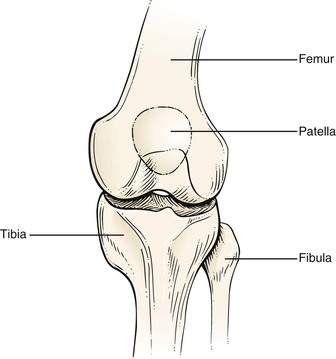

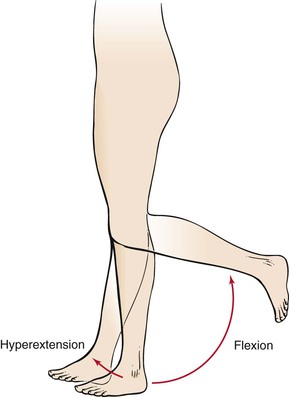

The anatomy of the knee is shown in Figure 17-15. The joint movements at the knee are flexion and hyperextension. These motions are illustrated in Figure 17-16.

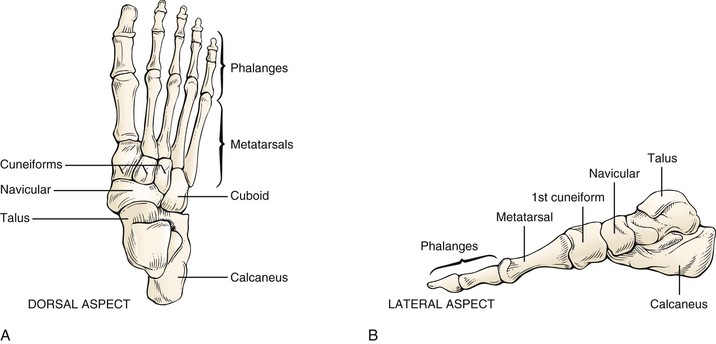

The anatomy of the ankle and foot is illustrated in Figure 17-17. There are 26 bones and 55 articulations in the foot. The bones can be divided into three regions: forefoot, midfoot, and rear foot. The forefoot is represented by the 14 bones of the toes and 5 metatarsals. The big toe (hallux) has two phalanges, two joints (interphalangeal [IP] joints), and two tiny, round sesamoid bones that enable it to move up and down. The sesamoid bones are about the size of a kernel of corn. These bones are embedded in the flexor hallucis brevis tendon, one of several tendons that exert pressure from the big toe against the ground and help initiate the act of walking: the propulsive phase of the gait cycle. The other four toes each have three bones and two joints. The phalanges are connected to the metatarsals by five metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints at the ball of the foot. The forefoot bears half the body’s weight and balances pressure on the ball of the foot.

The midfoot consists of the three cuneiform bones, the cuboid, and the navicular. The midfoot has five irregularly shaped tarsal bones, forms the foot’s arch, and serves as a shock absorber. The bones of the midfoot are connected to the forefoot and the hindfoot by muscles and the plantar fascia (arch ligament).

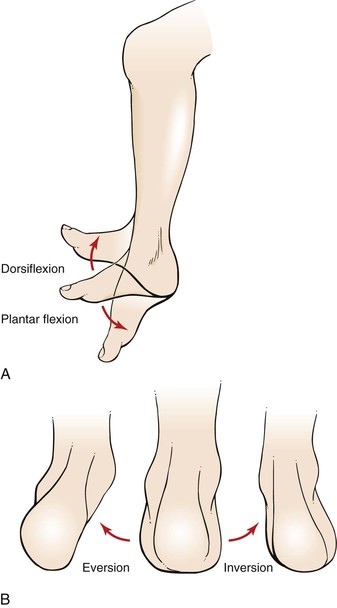

The rear foot is composed of the talus and the calcaneus. The foot contains two arches: the longitudinal in the midpart and the transverse in the forepart. The midtarsal joint is formed by the articulations of the navicular to the talus and the calcaneus to the cuboid. The largest tarsal bone is the calcaneus, the bottom of which is cushioned by a layer of fat. The attachment of the foot to the leg occurs through the talus. The joint movements at the ankle are dorsiflexion and plantar flexion. The motion of the subtalar joint is inversion and eversion. These motions are illustrated in Figure 17-18.

Figure 17–18 Range of motion at the ankle and foot joints. A, Dorsiflexion and plantar flexion. B, Eversion and inversion.

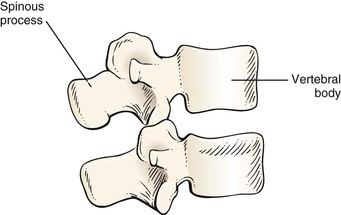

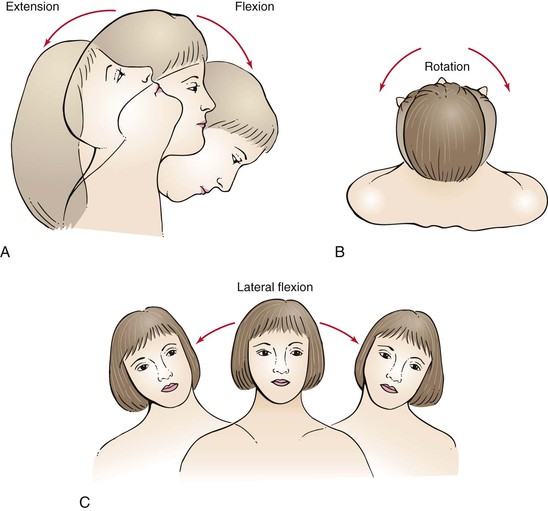

The anatomy of the cervical spine is shown in Figure 17-19. The joint movements of the neck are flexion and extension, rotation, and lateral flexion. These motions are illustrated in Figure 17-20.

Figure 17–20 Range of motion at the cervical spine. A, Flexion and extension. B, Rotation. C, Lateral flexion.

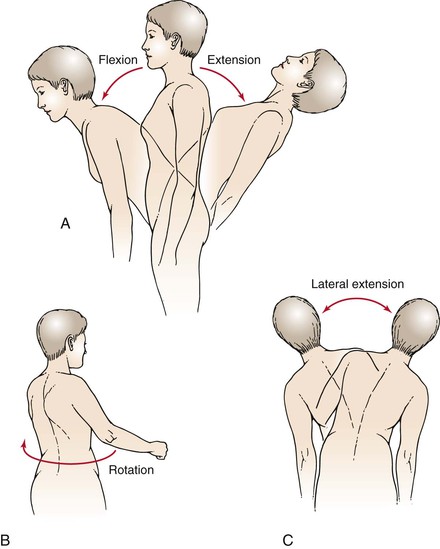

The anatomy of the lumbar spine is illustrated in Figure 17-21. The joint movements of the lumbar spine are flexion and extension, rotation, and lateral extension. These motions are illustrated in Figure 17-22.

Figure 17–22 Range of motion at the lumbar spine. A, Flexion and extension. B, Rotation. C, Lateral extension.

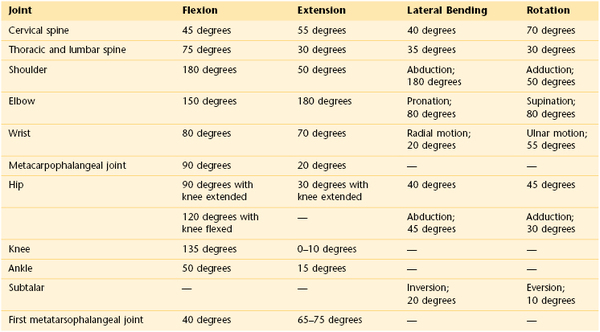

A summary of normal joint ranges of motion is shown in Table 17-5.

Review of Specific Symptoms

The most common symptoms of musculoskeletal disease are as follows:

The location, character, and onset of each of these symptoms must be ascertained. It is important for the interviewer to determine the time course of any of these symptoms.

Pain

Pain can result from disorders of the bone, muscle, or joint. Ask the following questions:

“When did you first become aware of the pain?”

“Where do you feel the pain? Point to the most painful spot with one finger.”

“Did the pain occur suddenly?”

“During which part of the 24-hour day is your pain worse: Morning? Afternoon? Evening?”

“Did a recent illness precede the pain?”

“What do you do to relieve the pain?”

“Is the pain relieved by rest?”

“What kinds of medications have you taken to relieve the pain?”

“Have you noticed that the pain changes according to the weather?”

“Do you have any difficulty putting on your shoes or coat?”

“Does the pain ever awaken you from sleep?”

“Does the pain shoot to another part of your body?”

“Have you noticed that the pain moves from one joint to another?”

“Has there been any injury, overuse, or strain?”

“Have you noticed any swelling?”

“Are other bones, muscles, or joints involved?”

Bone pain may occur with or without trauma. It is typically described as “deep,” “dull,” “boring,” or “intense.” The pain may be so intense that the patient is unable to sleep. Typically, bone pain is not related to movement unless a fracture is present. Pain from a fractured bone is often described as “sharp.” Muscle pain is frequently described as “crampy.” It may last only briefly or for longer periods. Muscle pain in the lower extremity on walking, described in Chapter 12, The Peripheral Vascular System, is suggestive of ischemia of the calf or hip muscles. Muscle pain associated with weakness is suspect for a primary muscular disorder. Joint pain is felt around or in the joint. In some conditions, the joint may be exquisitely tender. Movement usually worsens the pain, except with rheumatoid arthritis, in which movement often reduces the pain. Pain of several years’ duration rules out an acute septic process and usually malignancy. Chronic infection with tuberculosis or fungal infections may smolder for years before pain is present. The severity of the pain can often be assessed by determining the interval between the pain’s onset and the patient’s seeking medical attention.

The time of day when the pain is worse may be helpful in diagnosing the disorder. The pain of many rheumatic disorders tends to be accentuated in the morning, particularly on rising. Tendinitis worsens during the early morning hours and eases by midday. Osteoarthritis worsens as the day progresses.

Sudden onset of pain in a MTP joint should raise suspicion of gout. Entrapment syndromes are apt to radiate pain distally. Severe pain may awaken the patient from sleep. Rheumatoid arthritis and tendinitis often cause early awakening because of pain, particularly when the patient is lying on the affected limb.

Acute rheumatic fever, leukemia, gonococcal arthritis, sarcoidosis, and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis are commonly associated with migratory polyarthritis, in which one joint is affected, the disease subsides, and then another joint becomes involved.

Viral illnesses are commonly associated with muscle aches and pains. A recent history of a sore throat, with joint pain occurring 10 to 14 days later, is suspect for rheumatic fever. If rest does not relieve the pain, serious musculoskeletal disease may be present. The interviewer should keep in mind the possibility of referred pain. Pain from a hip disorder is frequently referred to the knee, especially in a child.

Weakness

Muscular weakness should always be differentiated from fatigue. Ascertain which functions the patient is unable to perform as a result of “weakness.” Is the weakness related to proximal or distal muscle groups? Proximal weakness is usually a myopathy; distal weakness is usually a neuropathy. A patient with the symptom of muscular weakness should be asked these questions:

“Do you have difficulty combing your hair?”

“Do you have difficulty lifting objects?”

“Have you noticed any problem with holding a pen or pencil?”

“Do you have difficulty turning doorknobs?”

“Do you have trouble standing up after sitting in a chair?”

“Have you noticed any decrease in your muscle size?”

“Do you have trouble with double vision? Swallowing? Chewing?”

A patient with proximal weakness of the lower extremity has difficulty walking and crossing the knees. A proximal weakness of the upper extremity is manifested by difficulty brushing the hair or lifting objects. Patients with polymyalgia rheumatica have proximal muscle weakness. This condition is discussed in Chapter 22, The Geriatric Patient. A distal weakness of the upper extremity is manifested by difficulty turning doorknobs or buttoning a shirt or blouse. Patients with myasthenia gravis have generalized weakness, diplopia, and difficulty swallowing and chewing.

Deformity

Deformity may be the result of a congenital malformation or an acquired condition. In any patient with a deformity, it is important to determine the following:

“When was the deformity first noticed?”

“Did the deformity occur suddenly?”

“Did the deformity occur as a result of trauma?”

Limitation of Motion

Limitation of motion may result from changes in the articular cartilage, scarring of the joint capsule, or muscle contractures. Determine the types of motion the patient can no longer perform easily, such as combing the hair, putting on shoes, or buttoning a shirt or blouse.

Stiffness

Stiffness is a common symptom of musculoskeletal disease. For example, a patient with arthritis of the hip may have difficulty crossing his or her legs to tie shoes. Ask the patient whether the stiffness is worse at any particular time of day. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis tend to experience stiffness after periods of joint rest. These patients typically describe morning stiffness, which may take several hours to subside.

Joint Clicking

Joint clicking is commonly associated with specific movements in the presence of dislocation of the humerus, displacement of the biceps tendon from its groove, degenerative joint disease, damaged knee meniscus, and temporomandibular joint problems.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree