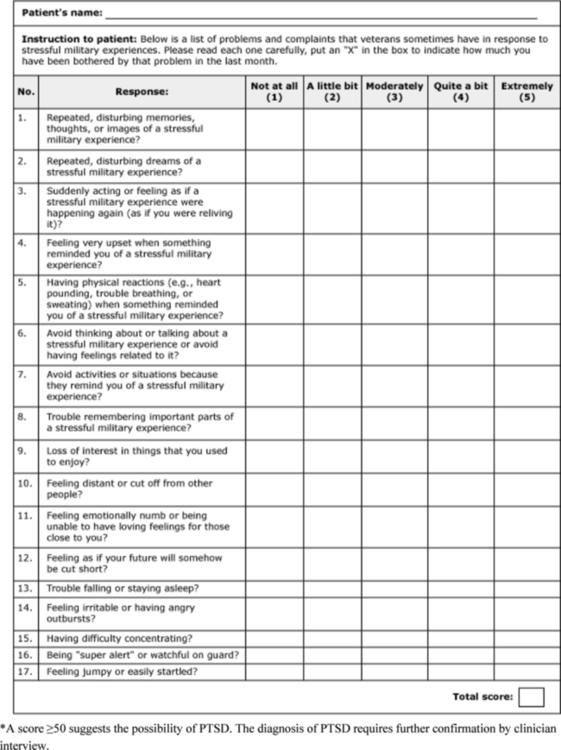

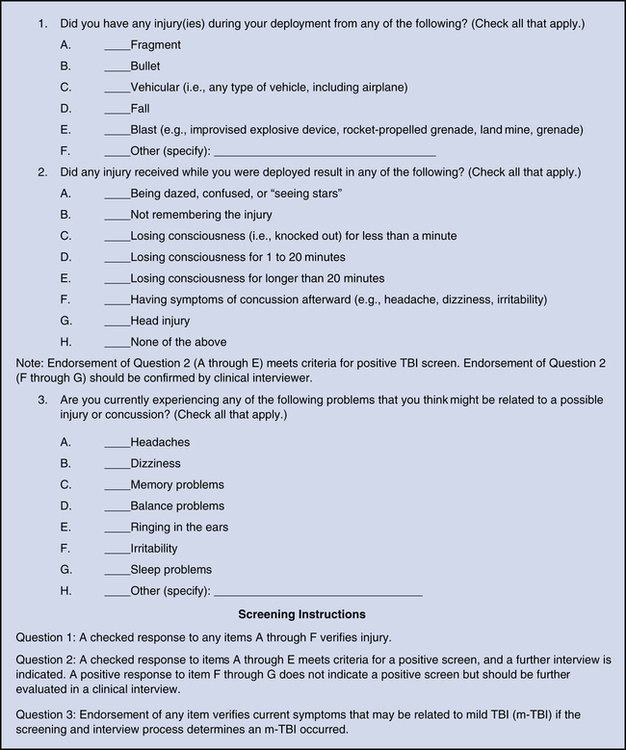

Stephen T. Lesieur, James L. Harris and Mary Fraggos 1. Describe the medical problems experienced by veterans. 2. Analyze the psychiatric disorders of veterans including posttraumatic stress, suicide, substance abuse, and sexual trauma. 3. Discuss the unique needs of women veterans. 4. Evaluate challenges in caring for veterans and their families and related nursing implications. Military troop deployment for the United States has historically extended to 130 countries. For the past 50 years, deployments in Japan, Germany, South Korea, and, more recently, Iraq and Afghanistan have included troops from the Army, Air Force, Navy, Marine Corps, Coast Guard, National Guard, and Reserves (Deployments and conflicts, 2011; Military Hub, 2011). The Department of Defense (DOD) estimates of military troop deployment in past wars and current deployments are presented in Table 39-1 (Sayer et al, 2010; Deployments and Conflicts, 2011). TABLE 39-1 U.S. MILITARY TROOP DEPLOYMENT Multiple illnesses, health risks, and concerns have been identified in military service personnel during past and current wars. For veterans of wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the incidence of mental health issues has become one of the leading health problems, second only to orthopedic issues (Rosenberg, 2008; Walker, 2010). Veterans and their families are confronted with many mental health issues that range from coping with initial and multiple deployments to depression, substance abuse, anxiety, family dissolution, homelessness, violence, and incarceration (Seal et al, 2007; Snell and Tusaie, 2008; Vietnam Veterans of America 2008). Military culture is complex and separate from civilian life. Deployment can adversely affect one’s health and psychological well-being. The toll of combat experiences can be substantial and not readily evident to health care providers and the public (Capps, 2010). The most pervasive and disabling experiences to military troops, families, and survivors are threats to psychological health and well-being. Examples of health risks and illnesses dating from the Vietnam War to the present global war on terror are identified in Table 39-2 (Vietnam Veterans of America 2008; U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs [VA] Office of Academic Affiliations, 2009). TABLE 39-2 HEALTH RISKS AND ILLNESSES FROM THE VIETNAM WAR TO THE PRESENT WAR ON TERROR There has been a significant increase in the number of veterans with traumatic brain injury (TBI) during recent military conflicts. The increase in number of identified cases may be related to more sophisticated diagnostic capabilities. TBI is a complex injury with a broad spectrum of symptoms and disabilities that can be disabling and can adversely impact quality of life (Snell and Halter 2010). It is discussed in Chapter 22. • Primary blast injuries occur as a direct injury from changes in atmospheric pressure. • Secondary injuries are caused by shrapnel or missiles that are propelled by the blast. • Tertiary injuries are caused when the individual is propelled by the blast and strikes the ground or other object. • Quaternary injuries result from the sequelae of the blast, such as burns, inhalation injuries, or even posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cognitive symptoms associated with TBI include problems with memory, concentration, language, and executive function. Emotional and behavioral problems may include depression, anxiety, increased mood lability, apathy, anger, irritability, impulsivity, and personality changes. Physiological problems related to TBI can include headache, pain, vision and hearing problems, dizziness, seizures, insomnia, appetite and weight changes, fatigue, and sexual dysfunction (Zeitzer and Brooks, 2008). Effectiveness of treatment is dependent on early and accurate diagnosis of symptoms. A useful three-question TBI self-report instrument for detecting TBI in troops returning from deployment in Iraq and Afghanistan is presented in Figure 39-1. PTSD is defined as an anxiety disorder that arises when a person has been exposed to a life-threatening traumatic event that provokes terror, horror, and helplessness, such as combat experiences (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). PTSD involves a range of physical, cognitive, emotional, and behavioral symptoms resulting from psychological trauma (see Chapter 15). The cause of PTSD is complex and involves many factors. There is evidence that the potential to develop PTSD may be influenced by genetics, early life experience, and health disparities as well as the exposure to a traumatic experience. PTSD consists primarily of three groups of symptoms: 1. Re-experiencing symptoms (one or more) 2. Avoidance symptoms (three or more) • Avoids thoughts or feelings reminding them of trauma • Avoids people, places, or things reminding them of trauma • Traumatic events blocked from memory • Decreased interest in activities 3. Hyperarousal symptoms (two or more): A diagnosis of acute stress disorder is made when criteria for PTSD have been met but symptoms have persisted for less than 30 days since the initial trauma. Early diagnosis and treatment of symptoms have been found to provide better outcomes for individuals with PTSD. A useful tool for diagnosis and screening for PTSD is the PTSD Checklist—Military Version (PCL-M), presented in Figure 39-2. Persons diagnosed with PTSD have a greater incidence of behavioral health problems and social dysfunction (Nayback, 2008; Jankowski, 2011). Approximately 18% to 20% of returning veterans who were deployed multiple times suffer from PTSD. The number of veterans seeking treatment for PTSD increased an estimated 70% from 2006 to 2007, and mental health treatment is the second largest treatment provided for returnees from Iraq and Afghanistan (National Security Archive, 2006).

The Military and Their Families

WAR

DEPLOYMENT ESTIMATES

Korean War (1950-1953)

1,790,000 (31% of active duty forces)

Vietnam War (1955-1975)

3,400,000 (39% of active duty forces)

Desert Shield and Desert Storm

584,342 (26% of active duty forces) plus

110,208 National Guard and reserve forces

Iraq and Afghanistan

>2,000,000 active duty/National Guard/reserve forces (27% deployed more than once)

WAR

HEALTH RISKS AND ILLNESSES

Vietnam War

February 28, 1961-May 7, 1975

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

Exposure to Agent Orange (dioxin) and other toxic chemical herbicides

Birth defects

Birth deficits in children born to female Vietnam War veterans

Hepatitis B, C

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)

Substance abuse

Military sexual trauma

Persian Gulf War

August 2, 1990-date undetermined, includes Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm

PTSD

Gulf War illnesses

Leishmaniasis

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)

Exposure to chemical smoke, chemical and biological agents, and depleted uranium

Immunizations

Substance abuse

Military sexual trauma

Global War on Terror

September 11, 2001-date undetermined, includes Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom

PTSD

Traumatic brain injury (TBI)

Multidrug resistant Acinetobacter

Leishmaniasis

Vision loss

Hearing loss, tinnitus

Traumatic amputation

Exposure to depleted uranium

Substance abuse

Military sexual trauma

Medical Disorders of Veterans

Traumatic Brain Injury

Psychiatric Disorders of Veterans

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The Military and Their Families

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access