The Legal and Ethical Side of Medical Insurance

Chapter objectives

After completion of this chapter, the student should be able to:

1. Discuss employer/employee liability.

2. List and explain the elements of a legal contract.

3. Name and briefly discuss important legislative acts affecting health insurance.

5. State the basic purposes and components of a medical record.

6. Describe the issues of medical record ownership, retention, access, and release.

7. Discuss the requirements of appropriate medical record documentation.

8. List legal/ethical responsibilities of ancillary staff members.

9. Identify HIPAA’s primary objectives.

10. Discuss HIPAA’s impact on healthcare personnel and patients, providers, and businesses.

12. Demonstrate an understanding of privacy/confidentiality laws.

13. List the exceptions to privacy/confidentiality laws.

14. Define and contrast fraud and abuse.

15. Analyze cause and effect of fraud and abuse in healthcare.

16. List ways to prevent fraud and abuse in the medical office.

Chapter terms

abandoning

abuse

acceptance

accountability

ancillary

binds

breach of confidentiality

competency

confidentiality

consideration

durable power of attorney

emancipated minor

ethics

etiquette

first party (party of the first part)

fraud

implied contract

implied promises

incidental disclosure

litigious

medical ethics

medical etiquette

medical (health) record

negligence

offer

portability

privacy

privacy statement

respondeat superior

second party (party of the second part)

subpoena duces tecum

third party

All there is to know about medical law and ethics would fill volumes of books. So as not to overwhelm you, this chapter attempts to zero in on what we think a health insurance professional should know to perform his or her job accurately and efficiently while maintaining confidentiality and sensitivity to patients’ rights.

The practice of medicine is, after all, a business—not unlike an auto body shop. The auto body shop’s goal is to fix cars; the medical facility’s goal is to fix people. Although the medical facility may be more charitable, the bottom line of both (unless the medical facility qualifies as a nonprofit organization) is to produce revenue.

The primary goals of the health insurance professional are to complete and submit insurance claims and to conduct billing and collection procedures that enable him or her to generate as much money for the practice as legally and ethically possible that the medical record will support in the least amount of time. To do this, the health insurance professional must be knowledgeable in the area of medical law and liability.

Medical law and liability

Medical law and liability can vary widely from state to state; however, some rules and regulations affect medical facilities in the United States as a whole. The health insurance professional should become familiar with the medical laws and liability issues in his or her state and should follow them conscientiously. The following sections discuss various facets of medical law and liability.

Employer Liability

In our litigious (quick to bring lawsuits) society, people tend more and more to hold physicians to a higher standard than those in other professions, and the slightest breach of medical care can end up as a malpractice lawsuit. Often, these lawsuits are settled out of court—not because the healthcare provider was afraid he or she would be found negligent and wanted to avoid publicity, but because of cost.

Employee Liability

No matter what the employee’s position is or how much education he or she has had, direct and indirect patient contact involves ethical and legal responsibility. Although we all know that professional healthcare providers have a responsibility for their own actions, what about the health insurance professional? Can he or she be a party to legal action in the event of error or omission? The answer is “yes”!

You may have heard the Latin term respondeat superior (ree-spond-dee-at superior). The English translation is “Let the master answer.” Respondeat superior is a key principle in business law, which says that an employer is responsible for the actions of his or her employees in the “course of employment.” For instance, if a truck driver for Express Delivery, Inc., hits a child in the street because of negligence (failure to exercise a reasonable degree of care), the company for which the driver works (Express Delivery) most likely would be liable for the injuries.

The ancillary members of the medical team (e.g., nurses, medical assistants, health insurance professionals, technicians) cannot avoid legal responsibility altogether. They also can be named as parties to a lawsuit. The healthcare provider usually bears the financial brunt of legal action, however, because he or she is what is referred to as the “deep pocket,” or the person/corporation with the most money.

Insurance and contract law

Because a health insurance policy and the relationship between a healthcare provider and a patient are considered legal contracts, it is important that the health insurance professional become familiar with the basic concepts of contract law.

Elements of a Legal Contract

To understand insurance of any kind, you have to have a reasonable knowledge base of the legal framework surrounding it. In other words, you must learn some basic concepts about the law of contracts. The health insurance policy, being a legal contract, must contain certain elements to be legally binding. These elements are as follows:

Let’s take a closer look at each of these five contract elements and apply them to the health insurance contract. We will follow a fictitious character—Jerry Dawson, a self-employed computer consultant—through this process.

Offer and Acceptance

Jerry visits Ned Nelson of Acme Insurance Company and tells him that he wants to purchase a health insurance policy for his family. Jerry completes a lengthy application form detailing his family’s medical history. Here, Jerry is making the offer—a proposition to create a contract with Ned’s company. Ned sends the application to his home office; after verifying the information, someone at the home office might say, “This guy and his family are okay; we’ll insure them.” This is the acceptance; Acme Insurance has agreed to take on Jerry’s proposition, or offer. The acceptance occurs when the insurance company binds (agrees to accept the individual[s] for benefits) coverage or when the policy is issued.

Consideration

Jerry receives his new insurance contract from Acme. The binding force in any contract that gives it legal status is the consideration—the thing of value that each party gives to the other. In a health insurance contract, the consideration of the insurance company lies in the promises that make up the contract (e.g., the promise to pay all or part of the insured individual’s covered medical expenses as set forth in the contract). The promise to pay the premium is the consideration of the individual seeking health insurance coverage.

Legal Object

A contract must be legal before it can be enforced. If an individual contracts with another to commit murder for a specified amount of money, that contract would be unenforceable in court because its intent is not legal (murder is against the law). Are we confident that this insurance policy between Jerry, our computer expert, and Acme Insurance Company is legal? We can rest assured a contract is legal if it contains all the necessary elements and whatever is being contracted (the object) is not breaking any laws.

Competent Parties

The parties to the contractual agreement must be capable of entering into a contract in the eyes of the law. Competency typically enters into the picture in the case of minors (except for emancipated minors—individuals younger than 18 years who are independent and living away from home) and individuals who are mentally handicapped. The courts have ruled that if individuals in either of these categories enter into a contractual agreement, it is not enforceable because the individuals might not understand all of the legal ramifications involved.

Legal Form

Most states require that all types of insurance policies be filed with, and approved by, the state regulatory authorities before the policy may be sold in that state. This procedure determines whether the policy meets the legal requirements of the state and protects policyholders from unscrupulous insurance companies that might take advantage of them.

Termination of Contracts

A contract between an insurance company and the insured party can be terminated on mutual agreement or if either party defaults on the provisions in the policy. The insurance company can terminate the policy for nonpayment of premiums or fraudulent action. The insured individual usually can terminate the policy at his or her discretion.

The contract between a healthcare provider and a patient (referred to as an implied contract, discussed in the next section) can be terminated by either party; however, when the provider enters into this contractual relationship, he or she must render care as long as the patient needs it and follows the provider’s instructions. The patient can terminate the contract simply by paying all incurred charges and not returning to the practice. The provider must have good reason to withdraw from a particular case and must follow specific guidelines in doing so. Some common reasons for a physician to stop providing care to a patient are

If it is determined that, for a specific reason, the physician desires to withdraw from a particular case, it is prudent that he or she

• explain the medical problems that need continued treatment; and

• state in writing the time (a specific date) of the termination.

It is important that these steps be followed to avoid a lawsuit for abandonment, because abandoning a patient—ceasing to provide care—is a breach of contract.

Medical law and ethics applicable to health insurance

Now that some of the fundamentals of contract law have been presented, we will take a brief look at basic medical law and liability as it applies to health insurance. First, it is important that the health insurance professional understand that the physician-patient relationship is a different kind of contract. The contract (or policy) between our computer consultant and Acme Insurance was a written contract. The relationship between a healthcare provider and a patient is an implied contract—meaning that it is not in writing but it has all the components of a legal contract and is just as binding. You have the offer (the patient enters the provider’s office in anticipation of receiving medical treatment) and the acceptance (the provider accepts by granting professional services). The consideration here lies in the provider’s implied promises (promises that are neither spoken nor written but implicated by the individual’s actions and performance) to render professional care to the patient to the best of his or her ability (this does not have to be in writing), and the patient’s consideration is the promise to pay the provider for these services. This implied contract meets the legal object requirement because granting medical care and paying for it are within the limits of the law. The healthcare provider, of legal age and sound mind, and the patient (or the patient’s parent or legal guardian, in the case of a minor or mentally handicapped individual) would constitute the competent parties—individuals with the necessary mental capacity or those old enough to enter into a contract. In an implied contract, however, there would be no legal form because it is not in writing.

You might have heard an insurance company referred to as a third party. In the implied contract between the physician and patient, the patient is referred to as the party of the first part (first party) in legal language and the healthcare provider is the party of the second part (second party). Because insurance companies often are involved in this contract indirectly, they are considered the party of the third part (third party).

Important legislation affecting health insurance

Several federal laws have evolved over the past few decades that regulate and act as “watchdogs” over the complicated and confusing world of health insurance.

Federal Privacy Act of 1974

The Federal Privacy Act of 1974 protects individuals by regulating when and how local, state, and federal governments and their agencies can request individuals to disclose their Social Security numbers (SSNs), and requiring that if that information is obtained, it be held as confidential by those agencies. Originally SSNs were to be used only for tax purposes; however, over the years, SSNs have been used for other things. With the growing problem of Social Security card fraud, individuals are encouraged to take steps to safeguard their SSNs. Many insurance companies formerly used SSNs for identification; however, in recent years, the trend is to use other numbering systems for identification.

Federal Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1980

The federal Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1980 (OBRA) states that Medicare is the secondary payer in the case of an automobile or liability insurance policy. If the automobile/liability insurer disallows payment because of a “Medicare primary clause” in the policy, however, Medicare becomes primary. In the event that the automobile/liability insurer makes payment after Medicare has paid, the provider (or the patient) must refund the Medicare payment.

Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982

The Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act (TEFRA) of 1982 made Medicare benefits secondary to benefits payable under employer group health plans for employees age 65 through 69 years and their spouses of the same age group.

Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1986

The Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA) of 1986 allows individuals to purchase temporary continuation of group health plan coverage if they are laid off, are fired for any reason (other than gross misconduct), or must quit because of an injury or illness. This coverage is temporary (18 months for the employee and 36 months for his or her spouse) and generally required by companies with 20 or more employees.

Federal False Claim Amendments Act of 1986

The Federal False Claim Amendments Act of 1986 expands the government’s ability to control fraud and abuse in healthcare insurance. Its purpose is to amend the existing civil false claims statute to strengthen and clarify the government’s ability to detect and prosecute civil fraud and to recover damages suffered by the government as a result of such fraud. The False Claims Amendments Act originally was enacted in 1863 because of reports of widespread corruption and fraud in the sale of supplies and provisions to the Union government during the Civil War.

Fraud and Abuse Act

The Fraud and Abuse Act addresses the prevention of healthcare fraud and abuse of patients eligible for Medicare and Medicaid benefits. It states that any person who knowingly and willfully breaks the law could be fined, imprisoned, or both. Penalties can result from the following:

• Using incorrect codes intentionally that result in greater payment than appropriate

• Submitting claims for a service or product that is not medically necessary

Federal criminal penalties are established for individuals who

Federal Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987

The federal Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 allows current or former employees or dependents younger than 65 years to become eligible for Medicare because of end-stage renal disease (ESRD). When the individual is diagnosed with ESRD and becomes eligible for Medicare, the employer-sponsored group plan is primary (pays first) for a period of up to 12 consecutive months, which begins when a regular course of dialysis is initiated or, in the case of a kidney transplant, the first month in which the individual becomes entitled to Medicare. If the individual’s condition is due to a disability other than ESRD, group coverage is primary and Medicare is secondary. (This applies only if the company has at least 100 full-time employees.)

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) is a federal statute that was signed into law in March 2010. This Act and the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 (also signed into law in March 2010) make up the health care reform of 2010. The laws focus on reform of the private health insurance market, provide better coverage for those with preexisting conditions, improve prescription drug coverage in Medicare, and extend the life of the Medicare Trust fund by at least 12 years. The healthcare reform acts have also provided for a new patient’s bill of rights. To learn more about this legislation and the new patient’s bill of rights, visit the Evolve site.

Medical ethics and medical etiquette

Most of us are familiar with the Oath of Hippocrates. It is a brief description of principles for physicians’ conduct, which dates back to the 5th century BC. Statements in the Oath protect the rights of the patient and oblige the physician voluntarily to behave in a humane and selfless manner toward patients. Although there is no such written or recorded oath for health insurance professionals, certain codes of conduct are expected of all individuals who work in healthcare—referred to as medical ethics and medical etiquette.

Medical Ethics

The word ethics comes from the Greek word ethos, meaning “character.” Broadly speaking, ethics are standards of human conduct—sometimes called “morals” (from the Latin word mores, meaning “customs”)—of a particular group or culture. Although the terms ethics and morals often are used interchangeably, they are not exactly the same. Morals refer to actions, ethics to the reasoning behind such actions. Ethics are not the same as laws, and if a member of a particular group or culture breaches one of these principles or customs, he or she probably would not be arrested; however, the group can levy a sanction (punishment) against this person, such as fines, suspension, or even expulsion from the group.

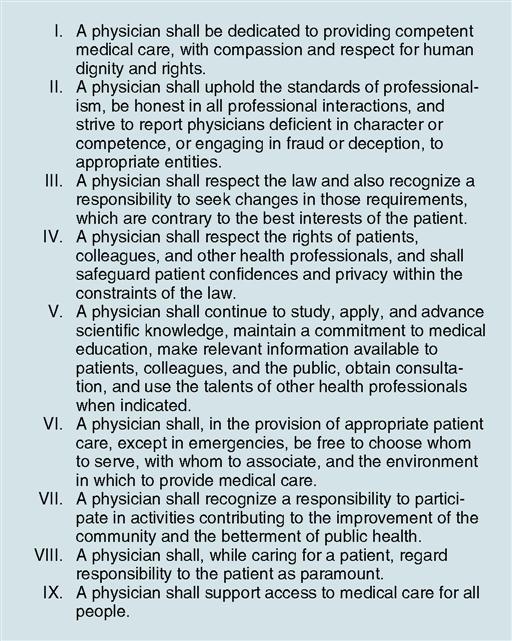

Ethics is a code of conduct of a particular group of people or culture. Medical ethics is the code of conduct for the healthcare profession. The American Medical Association (AMA) has long supported certain principles of medical ethics developed primarily for the benefit of patients. These are not laws but socially acceptable principles of conduct, which define the essentials of honorable behavior for healthcare providers. Fig. 3-1 provides a list of professional ethics from the AMA website.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree