The Ill Child in the Hospital and Other Care Settings

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

• Discuss the nurse’s role in various settings where care is given to ill children.

• List common stressors affecting hospitalized children.

• Describe the child’s response to illness.

• Discuss the stages of separation anxiety.

• Describe the factors that affect children’s responses to hospitalization and treatment.

• Discuss the psychological responses of families to the illness of a child in the family.

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/McKinney/mat-ch

Because of current trends in health care management, the care of ill children continues to move from the traditional acute-care hospital setting to community-based settings and the home. Hospitalized children are more acutely ill than in the past, and their stays are shorter. In addition, the hospitalized child is more likely to have a chronic or terminal disease or to have special needs that require specialized care. These changes do not mean that the need for pediatric nurses has diminished; their role is ever changing and expanding. Pediatric nurses will continue to care for children in hospitals, schools, clinics, and homes.

All children experience some form of illness at some time. The ways in which stressors and developmental needs are addressed are important factors in resolving the immediate crisis and in dealing with future illnesses. The nurse is often the first person the child sees when the child enters the health care system, and the nurse spends more time with an ill child than does any other health care provider. The nurse therefore has a unique opportunity to influence that child’s physical and emotional health.

Settings of Care

The Hospital

Entering the hospital is somewhat like visiting a foreign country. The language, culture, activities, and expectations may be unfamiliar to the child and the family. The nurse acts as a coordinator and provides a safe environment, both physically and emotionally. Being the coordinator includes activities as diverse as explaining the jargon (e.g., NPO, IV, “vitals”), explaining procedures that are often painful, and facilitating the parents’ access to hospital resources, such as social services, case managers, spiritual counselors, and ethics specialists. Above all, the nurse must educate the child and family about the disease process, its treatment, hospital procedures, and discharge issues.

Hospitalizations can be categorized according to length of stay, planned or unplanned admission, surgical or medical intervention, and outpatient (day) or inpatient status. Although they overlap, these categories provide a framework for examining the child’s experience.

Another variable is the type of facility. Children may be hospitalized in a pediatric hospital, on a pediatric unit within a general hospital, or in a general hospital that occasionally admits children. Pediatric units within a general hospital or hospitals that do not have a specific pediatric unit may not have as many child-oriented services as a pediatric hospital has. Special play areas and child-size equipment and fixtures are often not available in general hospitals. Also, staff members who do not care for children routinely, may feel less comfortable in those roles.

The nurse in this situation is aware of these challenges and can provide support for the child and the family, for example, by taking extra time when the child is admitted to explain routines and procedures or by placing the child close to the nurses’ station. This support might include moving a cot into the room for the parent and ordering special foods for the child. Sometimes it means removing part of the food from a tray that is about to be served so that the child is not overwhelmed by large servings intended for an adult. Ultimately, it means being sensitive to the needs of the child and the family.

24-Hour Observation

Many children with acute illnesses become ill quickly and recover quickly. For this reason, they may need acute-care for a short time, such as when they are dehydrated or are having an acute asthma episode. At the end of 24 hours, the child is evaluated to determine whether further hospitalization is needed or whether discharge with home care instructions is appropriate.

The nurse must prepare the child and family for discharge and assess the parents’ ability to care for the child at home. Instructions should be written in the language the parent can read, and the parent should be encouraged to ask questions. The nurse informs the parent about when to notify the primary health care provider in the event the child’s condition worsens. An awareness of cultural and language differences enhances the nurse’s ability to assess the child’s and family’s educational needs and develop an individualized teaching plan. For example, is the parent smiling because of contentment, or is the parent embarrassed to ask a question? Are parents nodding because they understand or are they too embarrassed to say they cannot understand English or cannot read? Many children’s hospital units have a policy of contacting caregivers 1 to 2 days after the child is discharged, especially if the child left the facility at the end of 24 hours. Arrangements are made with the parent for a convenient time to be contacted. This policy allows the nurse to check on the child’s condition and reinforce discharge teaching.

Emergency Hospitalization

An emergency admission can be distressing since there is little time for the child and family to prepare. The admission can be the result of traumatic injury or acute illness. The family may arrive at the hospital with little money, clothing, or other resources. Siblings may also be present, competing with the sick child for the parent’s attention. In addition to caring for the sick child, the staff may be called on to help meet the family’s basic needs for food, clothing, and a place to stay. A social service referral is appropriate in such situations.

Because of the intense level of activity in emergency departments, care of the family is often overlooked. The family may fear that the child will die or be permanently disabled. Although nurses may see many similar situations each day in which children do well, they must be sensitive to the family’s fears, keep the family informed of the child’s condition and care, and encourage a family member to stay with the child.

The time for preparing a child is usually limited in emergencies. Nurses must seize every opportunity to prepare children for the care they will receive. Holding and touching the child, talking softly, distracting the child, and involving the child in the procedure are methods of support used in emergencies. After the child is stable, the nurse returns and uses therapeutic communication to talk about the event. A child life specialist may also help the child express feelings. The use of dolls, puppets, and hospital equipment can aid children in communicating their feelings. (Chapter 34 provides more detailed information about caring for children and their families in an emergency setting.)

Outpatient and Day Facilities

Outpatient facilities have evolved in an effort to keep children out of the hospital unless absolutely necessary. The outpatient facility may be part of a hospital, or it may be free standing. The child arrives in the morning; undergoes a procedure, test, or surgical procedure; and goes home by the evening. Common procedures performed during such admissions include tympanostomy tube placement, hernia repair, tonsillectomy, cystoscopy, and bronchoscopy.

This mode of care has three main advantages: (1) it minimizes separation of the child from the family, (2) it decreases the risk of infection, and (3) it reduces cost. A disadvantage is that outpatient facilities that are not connected to a hospital may not be equipped for overnight stays. If complications develop that require continued observation and treatment, the child may have to be transferred to a hospital. This situation can be upsetting to the child and the family.

Although the procedure may be short, teaching the child and the parent is as important as in the acute-care setting. When possible, a tour of the facility before the procedure can decrease fear of the unknown. Parents have indicated that, although they like the idea of outpatient care, taking a child home afterward can be frightening.

Assessing the parent can assist the nurse in deciding whether the parent is capable of managing the child’s care at home or whether home health care is needed. Written instructions specific to the child and procedure are helpful and reassuring. At the very least, a follow-up phone call to the home should be required. Parents must also be encouraged to call the facility if they have any concerns, and they should be given other resources to contact after the facility closes. Families who live far from the health care facility may want to spend the night at a nearby hotel or consider an overnight admission.

Rehabilitative Care

After a serious illness or trauma, the child’s ability to function may change. After the acute situation has resolved, the child may be admitted to a rehabilitation hospital. Staff members from nursing, medicine, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and other areas collaborate to develop a treatment plan by which the child, family, and health professionals work to help the child regain previous abilities. Children with neurologic injuries, such as head injuries, or children with serious burns may thrive in this environment, which usually resembles a home setting with facilities available for the child to relearn activities of daily living.

Nurses in rehabilitative settings must balance nurturing and firm discipline as they help children reclaim independence. Parents often need encouragement and support because they are torn between “doing for” their child and watching the child struggle to function independently. Overprotection is a common reaction, and parents can be assisted in identifying the child’s developmental need to master the environment. The focus should be on what the child can do rather than on the child’s limitations.

The Medical-Surgical Unit

Children admitted to the hospital are usually acutely ill or have a chronic disease or disability that requires frequent, often long-term hospitalizations. (Care of the child with a chronic disease is discussed in Chapter 36.) The average length of hospital stay for the acutely ill child has shortened significantly, and the need for teaching has increased in proportion.

Preparation for a planned hospitalization is essential. Some hospitals provide an opportunity for the child to visit the hospital before admission, and many pediatric hospitals host preoperative parties or classes to introduce children to the strange sights and sounds they will experience during surgery. Literature is available from public libraries and hospital sources. These types of literature may be presented in pamphlet, video, and book formats. Parents should make sure that these present a realistic picture of the hospital experience (Ono, Hirabayashi, Oikawa, et al., 2008). Parents should encourage the child to talk about the hospitalization and answer questions honestly. Videos may also be available for family members to view together and then discuss.

The Intensive Care Unit

When a child is admitted to the intensive care unit, both the child and the family may experience increased stress related to factors such as the seriousness of the admitting diagnosis, the rapid onset of the illness, and the high-technology, unfamiliar environment (Aldridge, 2005). In addition, the child often is experiencing pain, uncomfortable procedures, noise, and constant lighting. In many instances, the child cannot eat or talk. Meanwhile, the parents are experiencing a parent’s worst fear—the possible loss of a child.

The child and family need intense emotional support. All the normal responses to hospitalization are magnified and need to be assessed. When possible, planned admissions to the intensive care unit (e.g., for cardiac surgery) should be preceded by visits to the unit or special classes that provide information about procedures and operations at a level the child can understand.

The parent should be encouraged to remain with the child and be kept informed of the child’s condition (Figure 35-1). Procedures, equipment, and treatments should be explained, in appropriate language, to both the child and the parent. If the parent leaves and the child’s condition changes or a new tube or piece of equipment has been added, the nurse should prepare the parent for the change before the parent sees the child. Nurses need to encourage parents to provide care and to touch their child as much as possible. The nurse’s active listening is essential.

Siblings of the seriously ill, hospitalized child can easily be overlooked. Siblings may need to talk, to be comforted, or to have the hospital experience explained to them. Parents may feel pulled between the ill child and the rest of the family. Often family members want to help but do not know what to do. Suggesting that a grandparent or other relative relieve a parent so that the parent has time with the ill child’s sibling can help both the parent and the child. Supporting parents by discussing options can relieve stress and may lead to solutions. Inclusion of family members in the provision of care, such as bathing and feeding, is important to both the family members and the child.

School-Based Clinics

The traditional areas of school health nursing that are still prevalent in many school systems include the following:

• Health care advice: The school nurse can be a source of referral for families in need of services.

School-based clinics have been part of health care for more than 25 years, but with the recent changes in health care delivery, this setting is now a site for expanding primary care. School-based clinics play an important role in providing care for children in remote rural communities and in underserved inner-city areas. School nurses, nurse practitioners, physicians, social workers, and other health care providers typically staff these clinics. This area of practice will continue to grow, and many believe that school-based clinics are the perfect setting for providing primary care for selected groups of children and adolescents because they are well situated to influence the health and well-being of underserved or disadvantaged students (Richardson, 2007).

Prevention remains the focus of school-based care as children learn healthy habits to prevent development of acute problems. Nurses identify children who need immunizations and provide immunizations when necessary. Screening that once required referral can often be handled on-site. Through school-based clinics, children can receive medical services in a timely manner and avoid expensive emergency visits. For example, a child with an earache at school can be seen on-site, treated, and sent home, if warranted. The child’s adherence to treatment can be monitored and a follow-up visit scheduled to determine whether treatment has been effective. Funding for school-based clinics is increasing, and they will continue to be a focus of health care delivery in the community.

Nurses in school-based clinics must be sensitive to parental concerns about certain topics in health care, especially areas related to sexuality (e.g., birth control, sexually transmitted diseases, abortion). Community involvement and support can dispel concerns and assist in setting guidelines for such clinics. School-based clinic nurses must also be team members who act in collaboration with other health care providers and have a strong background in preventive health care and the ability to think critically.

The school-based clinic provides a setting for parental education in preventive health care, growth and development, anticipatory guidance, parenting skills, and care of acutely and chronically ill children. The nurse respects the rights and wishes of the parents, but respecting parents’ wishes can be a challenge when the value systems of the health care provider and the parent differ. The pediatric nurse is a child advocate but must exercise caution unless the child is being harmed. (Child abuse is discussed in Chapter 53.)

The school nurse is an integral part of the health education program addressing both health and educational goals for school children (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP], 2008). A comprehensive health education program is an important part of the curriculum in most school systems, for children in kindergarten through high school (AAP Healthy Children, 2010). The goals for this program are to increase students’ health knowledge, generate positive attitudes toward health maintenance, and encourage healthy behaviors. To achieve these goals, active participation by students and involvement of parents are essential. Topics addressed include nutrition, disease prevention, physical growth and development, reproduction, mental health, drug and alcohol abuse prevention, consumer health, and safety (crossing streets, riding bikes, first aid, the Heimlich maneuver) (AAP Healthy Children, 2010).

Community Clinics

Community health clinics provide primary care for children and their families. In these settings, nurses, nurse practitioners, and physicians provide both case management of illness and health promotion. Because most children enter these settings during illness, preventive health care is integrated into the child’s acute-care. Support services and groups (e.g., social services, a dental clinic, daycare) may be available in the same center, and referrals to medical specialists and other health care providers are also available.

Although many children seen at community health clinics are ill, nurses must use the opportunity to obtain a health history, determine if immunizations are up to date, and assess nutritional status and growth and development. Needs for anticipatory guidance and education are evaluated as well. If the child is ill at the time of the visit, the nurse can set an appointment for the child to return for immunizations or other care that cannot be given when the child is ill (see http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/schedules/child-schedule.htm).

In some urban areas, nurses are involved in primary prevention and offer information and education about childhood immunization, the signs and symptoms of childhood illnesses, injury prevention, and parenting skills (Figure 35-2).

Home Care

Pediatric home care is the provision of skilled care within the child’s home. Nurses in this setting are part of a multidisciplinary team that often is comprised of physicians, respiratory therapists, physical therapists, speech therapists, occupational therapists, and social workers. Children cared for at home include those receiving respiratory therapy, having dressing changes, receiving total parenteral nutrition, or needing skilled care because of a chronic illness or an injury.

Nurses who work in home care should have previous hospital experience in their practice area. The nurse must be able to make independent decisions and think critically and should have good clinical, documentation, communication, and teaching skills. To meet the needs of each child and family, the nurse must understand various cultures and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Although the separation of the child from the family is not a problem in home health care, the child may display many other effects of illness, such as fear of the unknown, loss of control, anger, guilt, and regression. In addition, care is taking place in the family’s domain, and the nurse is a guest in the home. Family members may have to adjust to unfamiliar noises and equipment, such as special beds, ventilators, and intravenous (IV) pumps, in their home. They may feel that they have lost their privacy and cannot “be themselves” because someone outside the family is frequently present. Awareness of siblings’ needs is also a nursing goal in this setting.

The nurse’s role as a teacher is especially important because many tasks that the nurse might perform in the hospital are delegated to the family, with the nurse monitoring the care. In this case, the nurse acts as a case manager and coordinator of care.

Stressors Associated with Illness and Hospitalization

Age, cognitive development, preparation, coping skills, and culture influence a child’s reaction to illness. Previous experience with the health care system and the parent’s reaction to the illness also affect the child.

Each child is unique, so predicting reactions to an illness is often difficult. In general, hospitalization can create a number of threats or fears for children that have been grouped into the following five main categories: (1) bodily injury and pain, (2) separation from parents, (3) fear of the unknown or strange, (4) uncertainty about limits and expected behaviors, and (5) loss of control and autonomy (Visintainer & Wolfer, 1975). Educating parents about what to expect when their child is

hospitalized and supporting their participation in their child’s care decreases parental stress and enables them to better facilitate their child’s adjustment (Melnyk, Crean, Feinstein, et al., 2008; Melnyk, Feinstein, & Fairbanks, 2006).

Although preschoolers and young school-age children experience separation anxiety, it is most significant in infants and toddlers, especially those ages 6 to 30 months. In times of stress, anxiety related to separation increases.

Each age-group has its own fears related to pain and injury. The past decade has seen an expansion of knowledge about pain and its treatment, negating many erroneous beliefs about children and pain. Children quickly learn to associate health care activities and professionals with pain and injury. The fear is usually focused on injections (“shots”). (Chapter 39 discusses issues related to pain.)

A child’s feeling of having control over a situation has been shown to affect the child’s management of stressors (Board, 2005). If children believe that they have personal control over a situation, they are more likely to feel confident and master a task, whether it is holding still while a needle is inserted or lying still while radiography is performed.

Although specific fears are related to the child’s age, hospitalization puts all children at high risk for fears related to their unfamiliarity with the people, surroundings, and events. The child has not developed trust in the health care provider and therefore does not know what to expect. The child may have real or imagined fears. Will the nurse know when I am hungry or hurting? Will the nurse hurt me?

The Infant and Toddler

Separation Anxiety

Infants and toddlers, especially those between 6 and 30 months of age, often experience separation anxiety. Separation is this age-group’s major stressor, and it is traumatic to both the child and the parent. The child passes through several stages in reaction to the separation: protest, despair, and detachment (Box 35-1).

In the initial phase, known as protest, the child demonstrates distress by crying and rejecting anyone other than the parents (Figure 35-3). The child appears angry and upset. During the despair phase, the child feels hopeless and becomes quiet and withdrawn. Crying decreases and the child becomes apathetic. If separation from the parent continues, the child enters the detachment phase. During this phase, the child again becomes interested in the environment and begins to play. Nurses may misinterpret this phase as a positive sign that the child has adjusted to the hospitalization. In reality, the child has “given up.” If the parents return during this stage, the child may ignore them, and the parents may think that the child does not want to see them. This reaction, however, is a coping mechanism to protect the child from further emotional pain related to the separation.

A toddler exhibits separation anxiety by reacting with protest to leaving her parent’s arms. (Courtesy T.C. Thompson Children’s Hospital, Chattanooga, TN.) Rooming-in reduces the stress of hospitalization and provides opportunities for parent teaching.

Nurses in acute-care settings see the first two stages of separation—protest and despair—much more frequently than the final stage, detachment, which is more common in long-term separations. Parents may misunderstand their child’s behavior. They may even perceive the child’s reaction as a behavior problem. Nurses need to reassure parents that this reaction is a normal response to separation and that most children will not have any permanent effects from the event. As understanding of separation anxiety has evolved, visiting times for hospitalized pediatric patients have changed from structured hours to more flexible rooming-in situations (see Figure 35-3).

Most practitioners believe that, if separation can be avoided, the child will be much more resilient during a hospitalization. Infants and toddlers go through the stages of separation. For this age-group, the older the child’s age, the more elaborate the child’s protests. The child not only cries but also may cling to the parent, kick, and generally create a scene. Parents need to understand that this behavior is a sign of healthy parent-child attachment. The toddler may resist bedtime and eating and may have temper tantrums more frequently than normal for this age. Regression may occur in toileting and eating. Nurses need to explain to parents that regression is normal and to encourage parents to reinforce appropriate behavior while allowing the regressive behavior to occur.

Fear of Injury and Pain

Previous experiences, separation from parents, restraint, and preparation affect the reaction of infants and toddlers to pain and bodily injury. The young child views injury and pain concretely. Nurses who have worked with toddlers know that most toddlers react to any intrusive procedure, whether it is painful or not. (See Chapter 39 for a more extensive discussion of pain in infants and toddlers.)

Loss of Control

According to Erikson (1963), the major task of the toddler period is developing autonomy. Control is a major issue with this age-group. The toddler experiences the environment through all the senses and loves to explore the environment. At the same time, toddlers need sameness (rituals, routines). Because of the changes in growth and development taking place in the toddler, familiar rituals and routines (e.g., those for eating, sleeping, playing) provide reassurance and stability.

Hospitalization, which has its own set of rituals and routines, can severely disrupt the toddler’s life. The child may be confined to a crib, and the crib may have a cover over it. Because of safety issues, the child is not allowed to run in the halls. If the parents are unable to be with the child, the way the child is put to bed or bathed may be unfamiliar. Information obtained from parents about routines for feeding, going to bed, and playing can assist the nurse in maintaining usual and comforting routines. When children are unable to do things themselves, their sense of control and autonomy is weakened. They are frustrated and may have temper tantrums. Choices, even simple ones, can return some control to the child.

This lack of control is often exhibited in behaviors related to feeding, toileting, playing, and bedtime. The nurse should remember that each of these activities may have associated rituals and routines and that the child may also show some regression in these areas.

The Preschooler

Separation Anxiety

Separation anxiety occurs among preschoolers, but it is generally less obvious and less serious than in the toddler. Although the preschooler may already be spending some time away from parents at a daycare center or preschool, illness adds a stressor that makes separation more difficult.

The preschooler expresses the same protest as the toddler but tends to be less direct. The nurse may find a preschooler quietly crying because the parents have told the child to “act like a big boy (girl).” Children of this age may refuse to eat or take medications, and they may be generally uncooperative. They may repeatedly ask when their parents will be coming for a visit; with access to a phone, the child may constantly call the parents. All these behaviors are signs that the child is having difficulty coping with the situation.

Fear of Injury and Pain

The preschooler fears mutilation. The child who must have surgery affecting a limb or other body part feels greater fear. The preschooler generally does not understand body integrity. Children of this age report a predominant fear of pain and procedures that may cause pain such as injections (shots) and blood sample−taking/tests (Salmela, Salantera, & Aronen, 2009). Procedures that may be painful should be performed in the treatment room so children see their hospital rooms as safe places. Because of their literal interpretation of words, they often imagine treatments to be much worse than they are. A child’s imagination can become extremely active during illness. The preschooler may believe that the illness occurred because of some personal deed or thought or perhaps just because the child touched something or someone. (The preschooler’s specific reactions to pain are discussed further in Chapter 39.)

Loss of Control

The preschooler has attained a good deal of independence in self-care and has been given more independence at home, preschool, or daycare. Some children expect to maintain their independence in the hospital. For example, the preschooler may like to wander about the unit and may not be happy when restricted to the bed or room. Like the toddler, a preschooler likes familiar routines and rituals and may show some regression if not allowed to maintain some areas of control.

Guilt and Shame

Because their thinking is egocentric and magical, preschoolers may believe that their illness is somehow related to a thought or deed. This belief can lead to feelings of guilt, shame, and increased stress at a time when the child has to cope with several other stressors. Because the child typically does not share these feelings with adults, parents and caregivers must be aware of the possibility of guilt and shame in this age-group.

The nurse’s role is to assess the child for this type of thinking and, through therapeutic communication, assist the child in identifying unfounded fears and beliefs. The child may be able to relate perceptions of what is happening. The use of puppets, dolls, and drawings can help children deal with their feelings. A tremendous decrease in anxiety can result when the nurse helps the child identify a perceived punishment and then reassures the child that nothing the child did could cause the illness.

The School-Age Child

Separation

The school-age child is accustomed to periods of separation from parents, but, as in the preschooler, as stressors are added the separation becomes more difficult. The younger school-age child may already have been feeling separation anxiety related to starting school.

Older children may be more concerned with missing school and the fear that their friends will forget them. The need to adjust to an unfamiliar environment and the regression seen in ill children, however, increase the likelihood that some separation anxiety will take place.

Fear of Injury and Pain

The school-age child is concerned with body disability and death. The child is more relaxed about having a physical examination or having the eyes or an ear examined but is uncomfortable with any type of genital examination. School-age children want to know the reasons for procedures and tests, and they ask relevant questions about their illness. Because they can understand cause and effect, they can relate actions to becoming ill. Their parents may tell them that if they do not get enough rest, wear warm clothes, or eat nutritious meals, they will get a cold. If they become ill, they associate their actions with the disease. (For further discussion of pain in the school-age child, see Chapter 39.)

Loss of Control

School-age children are “movers and shakers.” They control their self-care and typically are highly social. They like being involved, and most fill their days with activities. Illness can change all these patterns. If children of this age have physical limitations, they can feel helpless and dependent (Figure 35-4). Anxiety in response to loss of control, environmental changes, and the hospitalization experience can alter the way school-age children appraise both the experience and the amount of resulting stress. School-age children can view the hospital experience as a threat. Children use coping strategies that include sleeping, talking with others, distraction (e.g., television, music, video games), and play. Ineffective coping can occur if the child sees the strategies as unsuccessful for regaining control (Board, 2005).

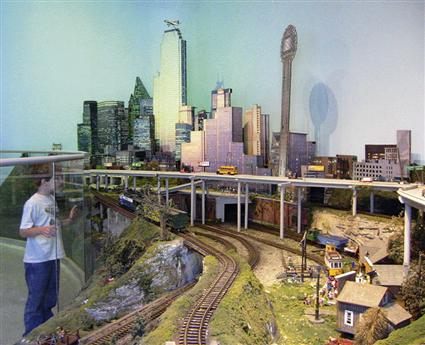

This model railroad “trainscape” in a pediatric hospital provides children and adults with a welcome respite from real-life stresses. (Courtesy Frolin Marek, Marek Mountain RR, www.Frolin.com.) Hospitalized teens need to interact with their peers, as they do when they are well. A lounge area that is separate from the playroom used by younger children fulfills this need.

Friends are important to children of this age-group, and school-age children may think that their friends will forget them while they are ill. They are also accustomed to making choices about meals and activities. By capitalizing on their abilities and needs, the nurse can encourage children of this age to become involved in their own care. School-age children can select their own menus, assist with some treatments, keep their rooms neat, and visit with other children when it is appropriate for both. With these opportunities for independence, children retain a sense of control, enhance their self-esteem, and continue to work toward achieving a sense of industry.

The Adolescent

Separation

Adolescents often are unsure whether they want their parents with them when they are hospitalized. Some enjoy the freedom and the period of independence. Others, in response to the stress of illness, become more dependent and want their parents nearby. A third group cannot decide what they want, and this situation can be frustrating to parents. All of these responses are consistent with normal adolescent growth and development.

Because of the importance of the peer group, separation from friends is a source of anxiety to the adolescent. Ideally, the peer group will support the ill friend. Some adolescents are reluctant to visit friends in the hospital, either because of their own health fears or because the reality of illness in someone their age is difficult for them to handle. Hospitalized adolescents may be upset if their friends simply go on with their lives, excluding them. It is important to provide special activity areas and other opportunities for the adolescent to meet and interact with other hospitalized adolescents (see Figure 35-4).

Fear of Injury and Pain

To the adolescent, appearance is crucial. Therefore an illness or injury that changes an adolescent’s self-perception can have a major impact. Even children who have seemingly adjusted to a chronic disease in their earlier years may have difficulty during adolescence simply because they do not want to be different. The adolescent who has diabetes may not want to eat different foods or take time out from an activity for injections. Adolescents do not want attention drawn to them, so they may eat the wrong foods and skip their medication.

Adolescents may also give the impression that they are not afraid, although they are terrified. Adolescents may think that being “cool” means being in control. They may question everything, or they may appear overly confident. Because of their concern with their bodies, they are guarded when any areas connected with sexual development are examined. Nurses need to be sensitive to adolescents’ concerns and reassure them that they are normal, if in fact they are. Some adolescents also believe that they are invincible and that nothing can hurt them or cause death. They may take risks and be nonadherent to treatment because they may not see the consequences of their behavior. (Pain management is discussed in Chapter 39.)

Loss of Control

Control is important to the adolescent. Thus, nurses must understand that many of the challenges they face caring for an ill adolescent stem from control issues. Giving the adolescent some control avoids endless power struggles. Behaviors exhibited in response to loss of control include anger, withdrawal, and general uncooperativeness.

Control issues can cause a major conflict between adolescents and parents. Parents often feel like “ping-pong balls” as they are bounced back and forth by a child who wants help one minute and rejects it the next. Parents who do not understand growth and development can become frustrated and angry over such behavior. Providing information about developmental issues, as well as information about the child’s illness and care, facilitates communication (Sarajärvi, Haapamäki, & Paavilainen, 2006).

Adolescents may also feel that they are losing control of their social lives as they sit on the sidelines of activities. Time to plan for the separation (e.g., scheduled surgery) allows a greater sense of control than an unplanned hospitalization (e.g., trauma).

Fear of the Unknown

The sights and sounds of the hospital can be frightening and confusing to children. The child may have many questions: Why are the nurses wearing masks? Why does that alarm keep ringing? Am I dying? Why are they putting tubes in me?

The child’s routines and rituals may have been disrupted, and the child may wonder what will happen next. Understanding these fears can assist the nurse in structuring care and teaching in a way that avoids unnecessary anxiety.

Regression

Children may regress in toileting or may cry for a bottle although they have been weaned for several months. They may want more attention at bedtime or have temper tantrums. The older child may react to separation by clinging or crying or may have fears about shadows on the walls or noises in the halls.

Parents may be overly concerned about regression. They should be told that the child might continue some regressive behaviors at home for a period of time following hospital discharge. The child may need more emotional support while the parent slowly returns the child to normal routines. If the child has regressed in toileting, the parent should wait until the child has returned to a daily routine and then begin the toilet training again. Behavior that is appropriate for the child’s age should be reinforced.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree