The Experience of Loss, Death, and Grief

Objectives

• Identify the nurse’s role when caring for patients who are experiencing loss, grief, or death.

• Describe the types of loss experienced throughout life.

• Describe characteristics of a person experiencing grief.

• Discuss variables that influence a person’s response to grief.

• Develop a nursing care plan for a patient and family experiencing loss and grief.

• Describe interventions for symptom management in patients at the end of life.

• Discuss the criteria for hospice care.

• Describe care of the body after death.

• Discuss the nurse’s own grief experience when caring for dying patients.

Key Terms

Actual loss, p. 709

Ambiguous loss, p. 710

Anticipatory grief, p. 710

Autopsy, p. 724

Bereavement, p. 709

Compassion fatigue, p. 726

Complicated grief, p. 710

Disenfranchised grief, p. 710

Disorganization and despair, p. 710

Grief, p. 709

Hope, p. 712

Hospice, p. 719

Maturational loss, p. 709

Mourning, p. 709

Necessary loss, p. 709

Normal (uncomplicated) grief, p. 709

Numbing, p. 710

Organ and tissue donation, p. 724

Palliative care, p. 719

Postmortem care, p. 724

Perceived loss, p. 709

Reminiscence, p. 711

Reorganization, p. 710

Situational loss, p. 709

Yearning and searching (separation anxiety), p. 710

![]()

Nurses have a primary duty to prevent illness and injury and help patients return to health. They also play a vital role in helping patients and families cope with things that cannot be changed and facilitate a peaceful death. Patients and families need expert nursing care through grief and death, perhaps more than at any other time. Caring for patients at the end of life requires knowledge and caring to bring comfort, even when the hope for cure or continued life is not possible. Although specialized roles and a sophisticated knowledge base for palliative and hospice care nurses have expanded greatly in the last two decades, nurses in all settings (i.e., residential facilities, hospitals, nursing homes, critical care units, and home health) provide most of the care for the seriously ill and dying.

Despite the pervasiveness of serious chronic illness and the high incidence of death in health care settings, many health care professionals feel apprehensive about providing end-of-life care (Weigel et al., 2007). Talking openly about death is discouraged in American society (i.e., in our everyday lives, our language, and even our thinking) (Matzo and Sherman, 2010). Terminal illness reminds friends and family members of their own mortality, which often causes them, sometimes unconsciously, to withdraw from the dying person. Nurses also grieve when witnessing the suffering of others.

You need to know that you are capable of providing the asset most valued by patients and family members at the end of life: a compassionate, attentive, and patient-centered approach to care. With each experience of caring for people at the end of life, you gain more confidence, courage, and compassion to accompany patients and family members through this intimate and meaningful phase of human transition. Your skills and knowledge base develop quickly if you have the desire and willingness to learn, be present, and seek the help needed to learn how to give excellent care at the end of life.

Scientific Knowledge Base

Loss

Throughout a lifetime people grieve the loss of multiple things: body parts or function, self-esteem, friendships, confidence, or income. Children develop independence from the adults who raise them, begin and leave school, change friends, begin careers, and form new relationships. From birth to death people form attachments and suffer losses. Illness also changes or threatens a person’s identity, and at some point everyone dies. People experience loss when another person, possession, body part, familiar environment, or sense of self changes or is no longer present (Table 36-1). The values learned in one’s family, religious community, society, and culture shape what a person regards as loss and how to grieve (Walter and McCoyd, 2009).

TABLE 36-1

| DEFINITION | IMPLICATIONS OF LOSS |

| Loss of possessions or objects (e.g., theft, deterioration, misplacement, or destruction) | Extent of grieving depends on value of object, sentiment attached to it, or its usefulness. |

| Loss of known environment (e.g., leaving home, hospitalization, new job, moving out of a rehabilitation unit) | Loss occurs through maturational or situational events or by injury/illness. Loneliness in an unfamiliar setting threatens self-esteem, hopefulness, or belonging. |

| Loss of a significant other (e.g., divorce, loss of friend, trusted caregiver, or pet) | Close friends, family members, and pets fulfill psychological, safety, love, belonging, and self-esteem needs. |

| Loss of an aspect of self (e.g., body part, job, psychological or physiological function) | Illness, injury, or developmental changes result in loss of a valued aspect of self, altering personal identity and self-concept. |

| Loss of life (e.g., death of family member, friend, co-worker, or one’s own death) | Loss of life grieves those left behind. Dying persons also feel sadness or fear pain, loss of control, and dependency on others. |

Life changes are natural and often positive. As people move forward in life, they learn that change always involves a necessary loss, which is a part of life. They learn to expect that most necessary losses are eventually replaced by something different or better. However, some losses cause them to undergo permanent changes in their lives and threaten their sense of belonging and security. The death of a loved one, divorce, or loss of independence changes life forever and often significantly disrupts a person’s physical, psychological, and spiritual health. A maturational loss is a form of necessary loss and includes all normally expected life changes across the life span. A mother feels loss when her child leaves home for the first day of school. A grade school child does not want to lose her favorite teacher and classroom. Maturational losses associated with normal life transitions help people develop coping skills to use when they experience unplanned, unwanted, or unexpected loss. Some losses seem unnecessary and are not part of expected maturation experiences. Sudden, unpredictable external events bring about situational loss. For example, a person in an automobile accident sustains an injury with physical changes that make it impossible to return to work or school, leading to loss of function, income, life goals, and self-esteem.

Losses may be actual or perceived. An actual loss occurs when a person can no longer feel, hear, see, or know a person or object. Examples include the loss of a body part, death of a family member, or loss of a job. Lost valued objects include those that wear out or are misplaced, stolen, or ruined by disaster. A child grieves the loss of a favorite toy washed away in a flood. A perceived loss is uniquely defined by the person experiencing the loss and is less obvious to other people. For example, some people perceive rejection by a friend to be a loss, which creates a loss of confidence or changes their status in a group. How an individual interprets the meaning of the perceived loss affects the intensity of the grief response. Perceived losses are easy to overlook because they are experienced so internally and individually, but they are grieved in the same way as an actual loss.

Each person responds to loss differently. The type of loss and the person’s perception of it influence the depth and duration of the grief response. For some individuals the loss of an object (e.g., home or treasured inherited gift) generates the same level of distress as the loss of a person, depending on the value the person places on the object. Chronic illnesses, disabilities, and hospitalization produce multiple losses. When entering an institution for care, patients lose access to familiar people and environments, privacy, and control over body functions and daily routines. A chronic illness or disability adds financial hardships for most people and often brings about changes in lifestyle and dependence on others. Even brief illnesses or hospitalizations cause temporary changes in family role functioning, daily activities, and relationships.

Death is the ultimate loss. Although it is a necessary part of the continuum of life and of being human, death represents the unknown and generates anxiety, fear, and uncertainty for many people. Death permanently separates people physically from important persons in their lives and causes fear, sadness, and regret for the dying person, family members, friends, and caregivers. A person’s culture, spirituality, personal beliefs and values, previous experiences with death, and degree of social support influence the way he or she approaches death.

Grief

Grief is the emotional response to a loss, manifested in ways unique to an individual and based on personal experiences, cultural expectations, and spiritual beliefs (Walter and McCoyd, 2009) (see Chapters 9 and 35). Coping with grief involves a period of mourning, the outward, social expressions of grief and the behavior associated with loss. Most mourning rituals are culturally influenced, learned behaviors. For example, the Jewish mourning ritual of Shivah incorporates the helping behaviors of the community toward those experiencing death, sets expectations for survivor behavior, and sustains the community with tradition and rituals (Bauer-Wu et al., 2007). The term bereavement encompasses both grief and mourning and includes the emotional responses and outward behaviors of a person experiencing loss (AACN, 2008). Recognizing that there are different types of grief can help nurses plan and implement appropriate care.

Normal Grief

Normal (uncomplicated) grief is a common, universal reaction characterized by complex emotional, cognitive, social, physical, behavioral, and spiritual responses to loss and death. Feelings of acceptance, disbelief, yearning, anger, and depression are displayed in normal bereavement grief. Although manner of death (violent, unexpected, or traumatic) poses greater risk to survivors, it does not always determine how an individual will grieve. Helpful coping mechanisms for grieving people include hardiness and resilience, a personal sense of control, and the ability to make sense of and identify positive possibilities after a loss.

Anticipatory Grief

A person experiences anticipatory grief, the unconscious process of disengaging or “letting go” before the actual loss or death occurs, especially in situations of prolonged or predicted loss (Simon, 2008). When grief extends over a long period of time, people absorb loss gradually and begin to prepare for its inevitability. They experience intense responses to grief (e.g., shock, denial, and tearfulness) before the actual death occurs and often feel relief when it finally happens. The idea that people actually grieve in anticipation (rather than following a loss) is debated by researchers. Another way to think about anticipatory grief is that it is a forewarning or cushion that gives people time to prepare or complete the tasks related to the impending death. However, this idea may not apply in every situation. Although forewarning is a buffer for some individuals, it increases stress for others, creating an emotional roller coaster of highs and lows.

Disenfranchised Grief

People experience disenfranchised grief, also known as marginal or unsupported grief, when their relationship to the deceased person is not socially sanctioned, cannot be openly shared, or seems of lesser significance. The person’s loss and grief do not meet the norms of grief acknowledged by his or her culture, cutting the grieving person off from social support and the sympathy given to persons with “legitimate” losses. The grieving person often wonders if he or she should call the experience a loss. Examples include the death an ex-spouse, a gay partner, or a pet or death from a stigmatized illness such as alcoholism or during the commission of a crime (Hooyman and Kramer, 2008; Walter and McCoyd, 2009).

Ambiguous Loss

Sometimes people experience losses that are marked by uncertainty. Ambiguous loss, a type of disenfranchised grief, occurs when the lost person is physically present but not psychologically available, as in cases of severe dementia or severe brain injury. Other times the person is gone (e.g., after a kidnapping or as a prisoner of war); but the grieving person maintains an ongoing, intense psychological attachment, never sure of the reality of the situation. Ambiguous losses are particularly difficult to process because of the lack of finality and unknown outcomes (Walter and McCoyd, 2009).

Complicated Grief

Some people do not experience a normal grief process. In complicated grief a person has a prolonged or significantly difficult time moving forward after a loss. He or she experiences a chronic and disruptive yearning for the deceased; has trouble accepting the death and trusting others; and/or feels excessively bitter, emotionally numb, or anxious about the future. Complicated grief occurs more often when a person had a conflicted relationship with the deceased, prior or multiple losses or stressors, mental health issues, or lack of social support. Loss associated with homicide, suicide, sudden accidents, or the death of a child has the potential to become complicated. Specific types of complicated grief include exaggerated, delayed, and masked grief.

Exaggerated Grief

A person with an exaggerated grief response often exhibits self-destructive or maladaptive behavior, obsessions, or psychiatric disorders. Suicide is a risk for these people.

Delayed Grief

A person’s grief response is unusually delayed or postponed, often because the loss is so overwhelming that the person must avoid the full realization of the loss. A delayed grief response is frequently triggered by a second loss, sometimes seemingly not as significant as the first loss.

Masked Grief

Sometimes a grieving person behaves in ways that interfere with normal functioning but is unaware that the disruptive behavior is a result of the loss and ineffective grief resolution (AACN, 2008).

Theories of Grief and Mourning

Knowledge of grief theories and normal responses to loss and bereavement will help you better understand these complex experiences and how to help a grieving person. Grief theorists describe the physical, psychological, and social reactions to loss. Remember that people who vary from expected norms of grief or theoretical descriptions are not abnormal. The variety of theories supports the complexity and individuality of grief responses. Although most grief theories describe how people cope with death, they also help to understand responses to other significant losses. A review of some classic grief theories follows.

Stages of Dying

Basing her research on interviews with dying people, Kübler-Ross (1969) describes five stages of dying in her classic behavioral theory: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. A person in the denial stage cannot accept the fact of the loss, which often provides psychological protection from a loss that the person cannot yet bear. When experiencing the anger stage of adjustment to loss, a person expresses resistance and sometimes feels intense anger at God, other people, or the situation. Bargaining cushions and postpones awareness of the loss by trying to prevent it from happening. Grieving or dying people make promises to self, God, or loved ones that they will live or believe differently if they can be spared death. When a person realizes the full impact of the loss, depression occurs. Some individuals feel overwhelmingly sad, hopeless, and lonely. In acceptance the person incorporates the loss into life; develops the capacity to have a breadth of emotions, even positive ones; and finds ways to move forward. The stages of dying are not linear. Patients will move back and forth through the stages.

Attachment Theory

Bowlby’s (1980) attachment theory, also a stage theory, describes the experience of mourning based on his studies of children separated from their parents during World War II. Attachment, an instinctive behavior, leads to the development of bonds between children and their primary caregivers. Relational bonds are present and active throughout the life cycle, and individuals later generalize them to persons in other relationships. Attachment behavior ensures survival because it keeps people close to those who offer love, protection, and support.

Bowlby describes four stages of mourning: numbing, yearning and searching, disorganization and despair, and reorganization. Numbing, the shortest stage of mourning, may last from a few hours to a week or more. The grieving person describes this stage as feeling “stunned” or “unreal.” Numbing protects the person from the full impact of the loss. Emotional outbursts of tearful sobbing and acute distress characterize the second bereavement stage, yearning and searching (separation anxiety). Common physical symptoms in this stage include tightness in the chest and throat, shortness of breath, a feeling of lethargy, insomnia, and loss of appetite. A person also experiences an inner, intense yearning for the lost person or object. This stage lasts for months or considerably longer. During the stage of disorganization and despair, a person endlessly examines how and why the loss occurred or expresses anger at anyone who seems responsible for the loss. The grieving person retells the loss story again and again and gradually realizes that the loss is permanent. With reorganization, which usually takes a year or more, the person begins to accept change, assume unfamiliar roles, acquire new skills, and build new relationships. Persons who are reorganizing begin to separate themselves from their lost relationship without feeling that they are lessening its importance.

Grief Tasks Model

Worden (1982) proposes a task-based grief theory. He describes how individuals actively engage in behaviors by responding to outside interventions to help themselves. Working through the grief tasks typically requires a minimum of a full year, although the time varies from person to person.

Rando’s “R” Process Model

Rando (1993) describes grief as a series of processes instead of stages or tasks. However, her processes are similar to the stages and tasks already described. Rando’s processes include recognizing the loss, reacting to the pain of separation, reminiscing, relinquishing old attachments, and readjusting to life after loss. Reminiscence is an important activity in grief and mourning. A person recollects and reexperiences the deceased and the relationship by mentally or verbally anecdotally reliving and remembering the person and past experiences.

Dual Process Model

Newer theories account for gender and cultural variations and address the limitations of theories focused mainly on internal, emotional responses to grief. The dual process model describes the everyday life experiences of grief as moving back and forth between loss-oriented and restoration-oriented activities (Wright and Hogan, 2008). Loss-oriented behaviors include grief work, dwelling on the loss, breaking connections with the deceased person, and resisting activities to move past the grief. Restoration-oriented activities such as attending to life changes, finding new roles or relationships, coping with finances, and participating in distractions provide balance to the loss-oriented state. The extent to which an individual engages in loss or restoration-oriented processes depends on factors such as personality, coping styles, or cultural practices.

Post Modern Grief Theories

Some experts believe the stage and task theories described previously lack empirical evidence, do not allow for cultural differences, and assume there is an end point in grieving (Walter and McCoyd, 2009). More recent grief theories take into consideration that human beings construct their own experiences and truths differently and make their own meanings when confronted with loss and death. Differences in social and historical context, family structure, and cognitive capacities shape an individual’s truths and grief experiences. No one’s grief follows a predetermined path.

Nursing Knowledge Base

Nurses develop plans of care to help patients and family members who are undergoing loss, grief, or death experiences. Based on nursing research, practice evidence, nursing experience, and patient and family preferences, nurses implement plans of care in acute care, nursing home, hospice, home care, and community settings. Extensive nursing education programs support the improvement of end-of-life care at every level of practice. The End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC) provides nurses with basic and advanced curricula to care for patients and families experiencing loss, grief, death, and bereavement (AACN, 2008); and nursing textbooks provide advanced discussions on multiple dimensions of palliative and end-of-life care (Ferrell and Coyle, 2010; Matzo and Sherman, 2010). In conjunction with the Hospice and Palliative Care Nurses Association, the American Nurses Association has developed the Scope and Standards of Hospice and Palliative Nursing Practice (2007). Professional nursing organizations such as the American Society of Pain Management Nurses and the American Association of Critical Care Nurses offer evidence-based practice guidelines for managing clinical and ethical issues at the end of life in many health care settings.

Factors Influencing Loss and Grief

Multiple factors influence the way a person perceives and responds to loss. They include developmental factors, personal relationships, the nature of the loss, coping strategies, socioeconomic status, and cultural and spiritual influences and beliefs.

Human Development

Patient age and stage of development affect the grief response. For example, toddlers cannot understand loss or death but often feel anxiety over the loss of objects and separation from parents. They sometimes express the sense of absence they feel with changes in eating and sleeping patterns, fussiness, or bowel and bladder disturbances. School-age children understand the concepts of permanence and irreversibility but do not always understand the causes of a loss. Some have intense periods of emotional expression. Young adults undergo many necessary developmental losses related to their evolving future. They leave home, begin school or a work life, or form significant relationships. Illness or death disrupts the young adult’s future and establishment of an autonomous sense of self. Midlife adults also experience major life transitions such as caring for aging parents, dealing with changes in marital status, and adapting to new family roles (Walter and McCoyd, 2009). For older adults the aging process leads to necessary and developmental losses. Some older adults experience age discrimination, especially when they become dependent or are near death; but they show resilience after a loss as a result of their prior experiences and developed coping skills (Box 36-1).

Personal Relationships

When loss involves another person, the quality and meaning of the lost relationship influence the grief response. When a relationship between two people was very rewarding and well connected, the survivor often finds it difficult to move forward. Grief resolution is hampered by regret and a sense of unfinished business, especially when people are closely related but did not have a good relationship at the time of death. Social support and the ability to accept help from others are critical variables in recovery from loss and grief. When patients do not receive supportive understanding and compassion from others, grief becomes complicated or prolonged (Hooyman and Kramer, 2008).

Nature of the Loss

Exploring the meaning a loss has for your patient helps you better understand the effect of the loss on the patient’s behavior, health, and well-being. Highly visible losses generally stimulate a helping response from others. For example, the loss of one’s home from a tornado often brings community and governmental support. A more private loss such as a miscarriage brings less support from others. A sudden and unexpected death poses different challenges than those in a debilitating chronic illness. When the death is sudden and unexpected, the survivors do not have time to let go. In chronic illness survivors have memories of prolonged suffering, pain, and loss of function. Death by violence or suicide or multiple losses by their very nature complicate the grieving process in unique ways (Walter and McCoyd, 2009).

Coping Strategies

Life experiences shape the coping strategies that a person uses to deal with the stress of loss. Patients rely first on familiar coping strategies. When the usual coping strategies do not work, they need new ones. Emotional disclosure (i.e., venting, talking about one’s feelings, or expressing anger or other negative feelings) is one way to cope with loss. Negative themes that are present when people talk about grief sometimes predict more distressful reactions (Maciejewski, 2007). However, some individuals cope better in situations of loss when they instead focus on positive emotions and optimistic feelings. Emotional disclosure is often accomplished by having people write about their feelings in letters to lost loved ones or personal journals.

Socioeconomic Status

Socioeconomic status influences a person’s ability to access support and resources for coping with loss and physical responses to stress (Cohen et al., 2006). When people lack financial, educational, or occupational resources, the burdens of loss multiply. For example, a patient with limited finances is not able to replace a car demolished in an accident and pay for the associated medical expenses.

Culture and Ethnicity

Culture and family or religious affiliation influences interpretations of loss and the ability to establish acceptable expressions of grief, which affects the ability to provide stability and structure in the midst of chaos and loss. Expressions of grief in one culture do not always make sense to people from a different culture (see Chapter 9). Try to understand and appreciate each patient’s cultural values related to loss, death, and grieving. Grief theories commonly used to understand loss and death have cultural limitations. For example, some theorists describe grief as a process of “work” or “tasks” that occurs in stages or on projected timelines. North Americans may better understand work, tasks, and time expectations for grief compared to other cultural groups not as defined by work achievements or with a different sense of time. Some cultural groups experience grief as a timeless, communal expression or state of being. Many people in Western European and American cultures hold back their public displays of emotion. In other cultures behaviors such as public wailing and physical demonstrations of grief, including survivor body mutilation, show respect for the dead. Core American cultural values of individualism and self-determination stand in contrast with communal, family, or tribal ways of life. Americans value and expect honesty and truth telling in end-of-life situations, but some cultures have strict taboos surrounding what should be discussed regarding the diagnosis and prognosis in serious illness (Erichsen et al., 2010; Johnstone and Kanitsaki, 2009). Cultural differences influence processes such as obtaining informed consent or making life-support decisions. Research has shown that ethnicity is strongly related to attitudes toward life-sustaining treatments during terminal illness and the use of hospice services (Rosenfeld et al., 2007).

Spiritual and Religious Beliefs

The care of seriously ill patients usually involves medical interventions to restore or maintain health. A contrasting set of practices (i.e., transformative strategies) acknowledge life limits and help dying people find meaning in suffering so they are able to transcend (go beyond) their personal existence. Transformative practices are associated with healing and spiritual or religious beliefs. Spiritual resources include faith in a higher power, communities of support, friends, a sense of hope and meaning in life, and religious practices. Spirituality affects the patient’s and family members’ ability to cope with loss. Positive correlations show that spiritual well-being, peacefulness, comfort, and serenity are all important aspects of a peaceful death (Kruse et al., 2007). Findings in the literature verify that religious beliefs provide a sense of structure in end-of-life situations and are linked to more positive attitudes toward death (Ladd, 2007).

Hope, a multidimensional concept considered to be a component of spirituality, energizes and provides comfort to individuals experiencing personal challenges. Hopefulness gives a person the ability to see life as enduring or having meaning or purpose. As a future-shaping, motivating force, hope helps patients maintain anticipation of a continued good, an improvement in their circumstances, or a lessening of something unpleasant (Clayton et al., 2008). With hope a patient moves from feelings of weakness and vulnerability to living as fully as possible. Maintaining a sense of hope depends in part on a person having strong relationships and emotional connectedness to others. On the other hand, spiritual distress often arises from a patient’s inability to feel hopeful or foresee any favorable outcomes. Spirituality and hope play a vital role in a patient’s adjustment to loss and death (see Chapter 35).

Critical Thinking

To provide appropriate and responsive care for the grieving patient and family, use critical thinking skills to synthesize scientific knowledge from nursing and nonnursing disciplines, professional standards, evidence-based practice, patient assessments, previous caregiving experiences, and self-knowledge. Critical thinking informs all steps of the nursing process (see Chapter 15).

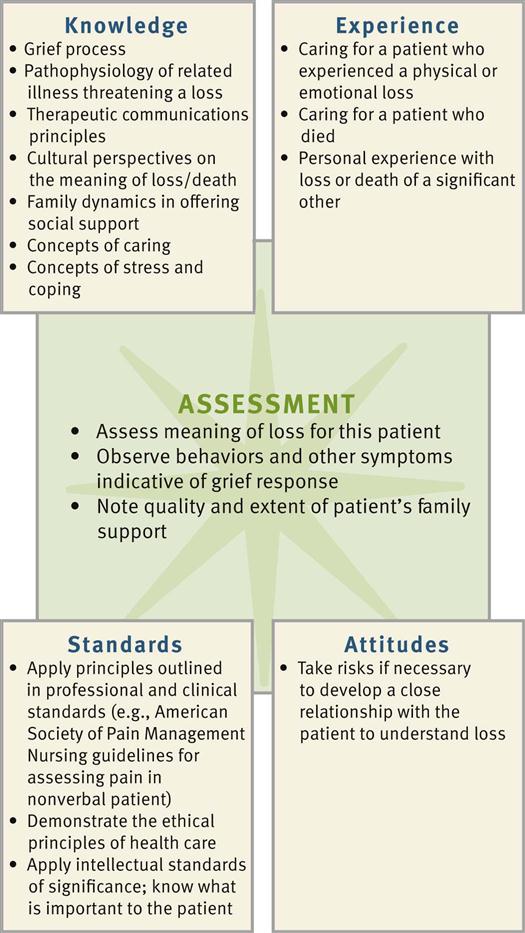

During the assessment phase use critical thinking to gather and analyze the data that lead to the selection of appropriate nursing diagnoses (Fig. 36-1). To understand a patient’s subjective experiences of loss, form assessment questions based on your theoretical and professional knowledge of grief and loss but then listen carefully to the patient’s perceptions. A culturally competent nurse also uses culture-specific understanding of grief to explore the meaning of loss with a patient.

Being familiar with commonly experienced responses to loss enables you to better understand a patient’s emotions and behaviors. Some patients ignore, lash out, plead with, or withdraw from other people as part of a normal response to loss. Instead of “taking things personally,” a critically thinking nurse integrates theory, prior experience, appreciation of subjective experiences, and self-knowledge to respond to the patient’s emotions with patience and understanding. In designing plans of care, use professional standards, including the Nursing Code of Ethics (see Chapter 22), the dying person’s bill of rights (Box 36-2), the American Nurses Association Scope and Standards of Hospice and Palliative Nursing Practice (2007), and clinical standards such as the American Society of Pain Management Nurses’ guidelines for pain assessment in the nonverbal patient (Herr et al., 2006).

Nursing Process

Apply the nursing process and use a critical thinking approach in your care of patients. The nursing process provides a clinical decision-making approach for you to develop and implement an individualized plan of care.

Assessment

During the assessment process, thoroughly assess each patient and critically analyze findings to ensure that you make patient-centered clinical decisions required for safe nursing care. A trusting, helping relationship with grieving patients and family members is essential to the assessment process. A caring nurse encourages a patient to tell his or her story, which then becomes a primary source of assessment data (Betcher, 2010). Look for opportunities to invite patients to share their experiences, being aware that attitudes about self-disclosure; sharing emotions; or talking about illness, fears, and death are shaped by an individual’s personality, coping style, and culture.

Through the Patient’s Eyes

Explore with patients their unique responses to grief or their preferences for end-of-life care, which may include advance directives. Patient perceptions and expectations influence how you prioritize your nursing diagnoses. To assess patient perceptions, you ask, “What is the most important thing I can do for you right now?” You usually gather information from patients first, but with advanced illness and as death approaches, patients often rely on family members to communicate for them. Encourage family members to share their goals and perceptions with you. Whether or not they accurately represent a patient’s viewpoints or wishes has been the topic of extensive research (Gardner and Kramer, 2010). Most often they provide valuable information about patient preferences and clarify misunderstandings or identify overlooked information. Assess patients’ and family members’ understanding of treatment options to implement a mutually developed care plan. Assessment of grief responses extends throughout the course of an illness into the bereavement period following a death. Patients with advanced chronic illness and their families eventually face end-of-life care decisions and should discuss the content of any advance directives together. Because most deaths are now “negotiated” among patients, family members, and the health care team, discuss end-of-life care preferences early in the assessment phase of the nursing process. If you feel uncomfortable in assessing a patient’s wishes for end-of-life care by yourself, ask a health care provider experienced in discussing these issues to help you. Communicate what you have learned about patient preferences during any RN hand-off, at health care team conferences, in written care plans, and through ongoing consultation (see Chapter 26).

Speak to patients and family members using honest and open communication, remembering that cultural practices influence how much information the patient shares. Keep an open mind, listen carefully, and observe the patient’s verbal and nonverbal responses. Facial expressions, voice tones, and avoided topics often disclose more than words. Anticipate common grief responses, but allow patients to describe their experiences in their own words. Open-ended questions such as “What do you understand about your diagnosis?” or “You seem sad today. Can you tell me more?” may open the door to a patient-centered discussion. Many people find it difficult to talk about loss, fear, death, or grief. The use of pauses, gentle questioning, and silence honors the patient’s privacy and readiness to talk. Talk to patients and family members in a private, quiet setting. Many times a patient wants to have family members present so everyone hears the same thing and has an opportunity to add to the conversation. However, some people want their concerns and questions addressed privately. Ask patients and family members about their preferences. As you gather assessment data, summarize and validate your impressions with the patient or family member. Information from the medical record and other members of the health care team, physicians, social workers, and spiritual care providers contributes to your assessment data.

Because of the importance of symptom management and priority of comfort in end-of-life care, prioritize your initial assessment to encourage patients to identify any distressing symptoms. Completing a thorough assessment is difficult when patients are in pain, anxious, depressed, or short of breath.

Grief Variables

Conversations about the meaning of loss to a patient often leads to other important areas of assessment, including the patient’s coping style, the nature of family relationships, social support systems, the nature of the loss, cultural and spiritual beliefs, life goals, family grief patterns, self-care, and sources of hope (Box 36-3). Use skills appropriate for assessing a patient’s culture, family, self-concept, or spiritual beliefs (see Chapters 9, 10, 33, and 35) to acquire a deeper understanding of his or her loss.

Knowing the commonly experienced reactions to grief and loss and grief theories guides your critical thinking and assessment skills. A single behavior can occur in all types of grief. If a grieving patient describes loneliness and difficulty falling asleep, consider all factors surrounding the loss in context. What was the loss? When did it occur? What was the meaning of the loss to the patient? For example, when your patient exhibits signs of a normal grief reaction, but you learn that the loss occurred 2 years ago, the patient’s response most likely indicates a complicated, chronic grief experience. Focus your assessment on how a patient is reacting to loss or grief and not on how you believe that patient should be reacting.

Grief Reactions

Use psychological and physical assessment skills to assess a patient’s unique grief responses. Most grieving people show some common outward signs and symptoms (Box 36-4). Analyze assessment data and identify possible related causes for the signs and symptoms that you observe. For example, after a significant loss a person has a sad affect, withdrawn behaviors, headaches, upset stomach, and decreased ability to concentrate. You associate these symptoms with several potential causes, including anxiety, gastrointestinal disturbances, medication side effects, or impaired memory. Careful analysis of the symptoms in context leads you to an accurate nursing diagnosis. Ask: How are the symptoms related to one another when they occur? When did they begin? Were they present before the loss? To what does the person attribute them?