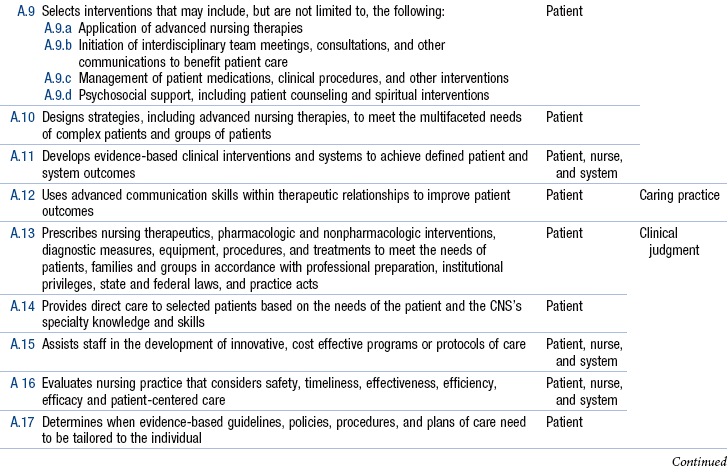

Chapter 14 Overview and Definitions of the Clinical Nurse Specialist, Clinical Nurse Specialist Practice: Spheres of Influence and Advanced Practice Nursing Competencies Current Marketplace Forces and Concerns Scope of Practice and Delegated Authority Institute of Medicine Future of Nursing Report NCSBN Consensus Model for Advanced Practice Registered Nurse Regulation and Implications for the Clinical Nurse Specialist Regional and Local Variations in Clinical Nurse Specialist Regulation Availability and Standardization of Educational Curricula for Clinical Nurse Specialists National Certification for Clinical Nurse Specialists Variability in Individual Clinical Nurse Specialist Practices and Prescriptive Authority Understanding the Similarities and Differences Between Clinical Nurse Specialists and Nurse Practitioners The clinical nurse specialist (CNS) role was created for the following reasons: (1) to provide direct care to patients with complex diseases or conditions; (2) to improve patient care by developing the clinical skills and judgment of staff nurses; and (3) to retain nurses who are experts in clinical practice (Cooper, Sparacino, & Minarik, 1990; Hamric & Spross, 1989). Expert clinical practice is the essence, the core value, of the CNS role. Historically, the role has been versatile, evolving, flexing, responsive, and adaptable to patient populations and health care environments, notably the same characteristics that have led to concerns regarding role confusion and ambiguity because of variability in implementation. However, the core strength of the CNS in providing complex specialty care while improving the quality of care delivery has remained central to the understanding of this advanced practice nurse (APN) role. Currently, the CNS is defined as an APN who practices in three substantive areas, as articulated by Lewandowski and Adamle (2009), to manage the care of complex and vulnerable populations, educate and support nursing and interdisciplinary staff, and facilitate change and innovation in health care systems. Lewandowski and Adamle developed these concepts of the three substantive areas of CNS practice in the context of the evolving health care environment by conducting an extensive literature review, based on the foundational work delineated by the National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists (NACNS). In their 2004 document, Statement on Clinical Nurse Specialist Practice and Education, NACNS described CNSs as practicing in the three interrelated spheres of client direct care, nurses and nursing practice, and organizations and systems. As noted earlier in this text, direct care of patients is the primary distinguishing feature of CNS practice (see Chapter 7) and interventions in the other two spheres are intended ultimately to affect the care of patients. Examples include interventions such as guiding and educating staff nurses in the nurses and nursing practice sphere and leading quality improvement projects and redesigning the delivery of care in the organizations and systems sphere. In the NACNS model, therefore, the client direct care sphere encompasses the interventions of the other two spheres to depict the centrality of the patient care focus. NACNS has been currently revising their statement at the time of this writing. In this chapter, we will use the NACNS spheres of influence and the further refined substantive areas of practice from Lewandowski and Adamle (2009) to illustrate the unique contributions of the role of the CNS and how the CNS role differs from other APN roles. Exemplar 14-1 describes a typical day in the life of a pediatric clinical nurse specialist. In spite of a core understanding of the nuances of the CNS role, the activities of CNSs are as varied as their individual specialty practices. The diversity of CNS specialties, differences in their individual practices, and practice differences seen among CNSs in the same institution has created confusion about what CNSs do. Unlike other APNs, whose primary role is to deliver direct patient care, the multifaceted CNS delivers direct patient care specifically to complex and vulnerable populations, educates and supports nurses and interdisciplinary staff, provides leadership to specialty practice program development, and facilitates change and innovation in health care systems (Lewandowski & Adamle, 2009). This variability in CNS practice, even within the same institution, has characterized the role since its creation. The definition of the CNS role has remained deliberately broad so that CNSs can respond to changing clinical environments. For example, a unit- or population-based critical care CNS with an experienced, certified specialty staff may balance his or her time equally among direct patient care activities, educating interdisciplinary staff, and system-wide improvements. Conversely, if a preventive cardiology CNS works in an outpatient clinic in the same institution and sees a panel of patients as a provider of expert specialty care, that CNS practice may focus more on direct patient care and less on education and system-wide improvements. Several clinical, staff, and system variables must be weighed when planning for CNS positions and implementing the role, including the number, type, and background of nurses and other clinical staff, clinical, educational, or institutional resources, and patient population, acuity, and outcomes. This versatility in CNS practice has continued to challenge the CNS role definition and understanding of the impact of CNSs on clinical outcomes and costs of care. Role confusion and variability, regulatory drivers, and fiscal retrenchment in the last 20 years have resulted in the loss of CNS positions in many parts of the country to save hospitals money without jeopardizing direct care registered nurse (RN) positions. The CNS role is the only APN role to decrease in numbers in the most recent national RN survey (see Chapter 3). CNS clinical practices are shaped by many factors, such as health care agency needs, community needs, payor and other regulatory agency mandates, statutory limitations, supervisor requests, and individual CNS interests. Over the past few decades, CNSs have been able to change their practices in response to these influential forces. Clarifying the work and core competencies of all CNSs, regardless of specialty, has been complicated historically because specialty organizations have established varying educational, competency, and practice standards for CNSs (e.g., critical care, oncology, neuroscience specialties). NACNS was not established until 1995 (see Chapter 1). The NACNS itself has acknowledged that advanced practice organizations for the other three APN roles had a significant head start in defining competencies and influencing health policies related to advanced practice nursing (NACNS, 2004b). The American Nurses Association (ANA), many specialty organizations, and APN leaders have worked hard to define CNS practice, define standards and competencies, and develop CNS curricula (see Chapters 1 and 2). More work, however, is required to educate colleagues, administrators, and the public about the role of the CNS. For reasons outlined later in this chapter, and discussed in Chapter 21, we believe that CNSs and the nursing profession are at a critical juncture for the survival of the role of the CNS. For the purposes of clinical practice and licensure, accreditation, credentialing, and education (LACE), the work and contributions of CNSs as APNs must be made unambiguously clear. The ANA has defined APNs as nurses who “practice from both expanded and specialized knowledge and skills” (ANA, 2003, p. 9). An expanded knowledge base and skill set refers to the “acquisition of new practice knowledge and skills, including the knowledge and skills that authorize role autonomy within areas of practice that may overlap traditional boundaries of medical practice” (ANA, 2003, p. 9; see Chapter 3). Specialized knowledge and skills are defined as “concentrating or delimiting one’s focus to part of the whole field of professional nursing” (ANA, 2003, p. 9). According to the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) Consensus Model for advanced practice registered nurse (APRN) regulation, a defining factor for all APNs is that a significant component of the education and practice be focused on direct care of individuals (NCSBN, 2012b). If CNSs want to be recognized nationally, statewide, or locally as APNs, they must have a significant component of direct care of individuals in their role. If the focus is mainly on educating nursing and/or interdisciplinary staff or process improvement without direct care of individuals, the clinician is not practicing in the role of a CNS (Cronenwett, 2012). New opportunities for expanded CNS practices have presented themselves with the introduction of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2011). Successful CNSs have consistently delivered direct and indirect care that improves patient care quality and outcomes, patient safety, and nursing practice and that ensures efficient use of resources, cost efficiency, cost savings, and revenue generation (NACNS, 1998, 2004b; Newhouse, Stanik-Hutt, White et al., 2011; see Chapter 23). CNSs’ clinical acumen and expertise are not limited to their patients’ physiologic and psychological needs. Their clinical expertise permeates the other elements of their multifaceted responsibilities—education, evidence-based practice (EBP), health policy, organizational factors, and political change—and they are highly qualified to lead interdisciplinary teams in health care reform. The purpose of this chapter is to describe the core competencies, current marketplace challenges, and future directions for CNSs. Although other models of CNS practice have been described (see Chapter 2), the NACNS’s three spheres of influence and Hamric’s seven competencies (see Chapter 3 and Chapters 7 through 13) will primarily be used to organize and explain CNS practice in this chapter. CNS students are encouraged to familiarize themselves with the NACNS Statement on Clinical Nurse Specialist Practice and Education (2004b) and with specialty-specific standards (e.g., the Emergency Nurses Association [2011] competencies for clinical nurse specialists) to understand the discussion of spheres and competencies better. In addition, readers should also be aware of the substantive areas of CNS practice reported by Lewandowski and Adamle (2009) to understand a more recent articulation of CNS practice. To be successful, a CNS must understand and apply the seven competencies of advanced practice nursing across the three spheres of influence, regardless of setting or specialty (Sparacino & Cartwright, 2009). The NACNS (2010), along with other nursing organizations, has endorsed a list of comprehensive, entry-level competencies and behaviors expected of graduate programs in the preparation of CNSs (Table 14-1). From the National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists. (2010). Clinical nurse specialist core competencies (www.nacns.org/docs/CNSCoreCompetenciesBroch.pdf). Advanced practice competencies are categories of proficient performance and include specific knowledge and skill sets. The direct care of patients and families is the central competency in Hamric’s model (see Fig. 2-4) and links every other competency. According to the NACNS model, the impact and influence of CNSs are felt within three spheres of influence—direct care of patients or clients,* nurses and nursing practice, and organizations and systems (NACNS, 2004b; see Fig. 2-2). Both the Hamric and NACNS models emphasize the importance of direct care; clinical expertise and direct care are basic to CNS practice. For this reason, the direct care of patients or clients sphere is the largest sphere in the NACNS model and encompasses the other two spheres. For examples of activities in this sphere, as expanded on by Lewandowski and Adamle (2009), see Box 14-1. CNSs demonstrate all seven competencies across the three spheres of influence and often execute some competencies simultaneously. They exert influence in the nurses and nursing practice sphere by caring for patients directly and by serving as coaches, guides, and role models for nursing staff and other caregivers. They provide consultation. They demonstrate EBP competencies by working with staff to develop, implement, and evaluate EBPs. They may collaborate in clinical research, an activity likely to affect all three spheres of influence. Similarly, they collaborate and facilitate team development, assess and intervene to alleviate the moral distress inherent in clinical care, and create environments that support clinicians’ ethical decision making. See Box 14-2 for examples, as described by Lewandowski and Adamle (2009). CNSs exert influence in the organizations and systems sphere by providing clinical and systems leadership in many ways, whether articulating nursing issues to team members, advocating for a patient, taking a stand on behalf of nurses, or evaluating the quality and cost-effectiveness of technologies and care processes. Box 14-3 lists activities in this sphere (Lewandowski & Adamle, 2009). Throughout all three spheres, CNSs apply the nursing process; assessment, planning, implementation, and evaluation activities are designed to improve the care of patients, develop nurses, and improve the systems in which nurses work and care is delivered. Experienced CNSs understand that activities in each sphere of influence and their advanced practice competencies exert reciprocal influences on each other. Implementing competencies across the three spheres can result in improvements in clinical outcomes, patient safety, patient-family satisfaction, resource allocation, professional nursing staff knowledge and skills, health care team collaboration, and organizational efficiency (Murray & Goodyear-Bruch, 2007; Ryan, 2009; Vollman, 2006). CNS practice includes advanced assessment skills and the integration of “biophysical, psychosocial, behavioral, sociopolitical, cultural, economic, and nursing science” (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], 2006b, p. 16) into specialized, expert nursing practice. Skills (clinical, advanced communication, and relational) and knowledge (theoretical, practical, and particular) are essential, but practical wisdom is a hallmark of advanced practice nursing (Oberle & Allen, 2001). Many authors have described strategies for successfully implementing the expert clinician dimension, building on the conceptual foundations of previous authors (Duffy, Dresser, & Fulton, 2009; Fulton, Lyon, & Goudreau, 2010; Zuzelo, 2010). Each strategy is highly dependent on the individual CNS and his or her practice setting and can fluctuate from year to year in relation to the prevailing health care environment. It is easy for the direct care component of the role to be overemphasized or underemphasized because of institutional priorities and competition for CNS expertise. The unique skill set of CNSs may result in them being continually pulled away from direct care to lead projects that are of high priority for the institution. Conversely, if an institution recognizes value only in the revenue generation component of direct care, the CNS may be required to focus exclusively on that component of the role. The CNS role is optimally enacted when CNSs have the opportunity to use what they have learned from direct clinical practice to improve care for individual patients, families, and patient populations, whether that occurs at the patient-CNS interface, through nursing personnel, or through organizational improvements. • Evaluate the quality, effectiveness, efficiency, and safety of patient care and determine whether inadequacies are the result of a lack or ineffective use of nursing resources, insufficient equipment and supplies, or systems’ inefficiencies; this assessment by CNSs has been characterized as surveillance (Brooten, Youngblut, Deatrick, et al., 2003; see Chapter 7). • Demonstrate one’s clinical competency and maintain clinical expertise, thereby role modeling clinical behaviors, establishing credibility, and maintaining team relationships and collegial trust. • Identify nursing staff learning needs, including knowledge and skill development. • Refine one’s clinical expertise and reflective abilities. Direct care, or direct clinical practice, refers to CNS activities and responsibilities that occur within the patient-nurse interface (see Chapter 7). For many years, a CNS’s direct clinical practice was not clearly linked to measureable goals, such as patient outcomes or resource use. Thus, few data were available to justify the role and correlate its expense with the cost avoidance and quality improvement aspects of the role when health care institutions were restructuring their operating systems. However, most patients requiring the expertise of a CNS are sicker, more frail, and in need of specialized expert care. Clinical studies with high-risk patients, such as very-low-birth-weight (VLBW) infants, women with a high-risk pregnancy, and older adults with cardiac diagnoses, have consistently shown improved patient outcomes and reduced health care costs when CNSs and other APNs were directly involved with patient care, including assessing, teaching, counseling, and negotiating systems (Dejong & Veltman, 2004; Murray & Goodyear-Bruch, 2007; Ryan, 2009; Vollman, 2006). A CNS’s clinical practice interventions may be continuous, in which the CNS carries a consistent caseload, or time-limited, regular, or episodic, in which the CNS cares for complex cases as they arise (Koetters, 1989). Examples of regular ongoing care include the following: providing care for high-risk newborns in a pediatric special care clinic; providing psychotherapy, medication management, and other specialized nursing care for patients requiring mental health care; delivering total patient care to the first patients in an innovative surgery program; or providing yearly comprehensive neurologic care for children with spina bifida in a hospital-based clinic. Episodic care helps a CNS assess and intervene in a particular problem. Examples of episodic care include planning and coordinating a patient’s complex hospital discharge, facilitating a support group for families of children with hydrocephalus, and providing total patient care (similar to a staff nurse but with a different lens) to determine the feasibility of proposed changes in patient care or other system changes. Involvement in regular or episodic care enables CNSs to identify systems problems that interfere with care and require CNS intervention. Examples include lack of staff knowledge, the need for clinical policies or procedures, and the need for conflict mediation among team members. For each clinical situation, a CNS takes a comprehensive approach, using discriminative judgment, advanced knowledge, and expert skills, including expertise in the technical, humanistic, and organizational aspects of care. In these situations, CNSs are particularly skilled at the use of surveillance, quickly identifying patient and system issues and intervening to avoid further complications. A CNS intervention may be as simple as assisting a patient and family navigate a hospital’s bureaucracy. A CNS knows how and when to break the rules and when to bypass organizational or philosophical roadblocks, thus ensuring the focus on the patient and family and a successful outcome. Patient safety is integral to all aspects of direct and indirect clinical practice, including CNS availability to and support of novice nurses (Altmiller, 2010; Ebright, Urden, Patterson, et al., 2004). The CNS’s familiarity with National Patient Safety Goals, the Agency for Health Research and Quality (AHRQ) patient safety network, teaching strategies from Quality and Safety Education in Nursing (QSEN), and Open School at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) are resources that can help the CNS keep abreast of patient safety issues (AHRQ, 2012; IHI, 2012; QSEN, 2012; The Joint Commission [TJC], 2012). It is this direct clinical practice that empowers a CNS to assume a leadership role in evaluating patient safety, exploring root cause analyses, and preventing adverse events. A CNS facilitates change, influences others, and builds an atmosphere of trust in situations in which adverse events are investigated. Exemplar 14-2 illustrates how one of the authors (CC), a pediatric CNS, uses her professional competencies to provide expert care to a specific patient population and demonstrates the importance of direct care to execution of the other CNS competencies. CC coordinates health care services for a large pediatric craniofacial population, specifically infants with craniosynostosis. The pediatric neurosurgeon with whom CC works uses a new, less invasive technique to correct craniosynostosis in young infants. To inform families and referring health care providers about craniosynostosis treatment in her hospital, CC has developed and maintains a craniosynostosis link on the institution’s website. This minimally invasive surgical treatment—and its follow-up—has drawn patients from a large geographic area. One of the essential components of the CNS role is that of expert coach. This role of coach, guide, or educator is one that facilitates transition from one situation to another and depends on the interaction of technical, clinical, and interpersonal competencies and self-reflection (see Chapter 8). Its development is also influenced by scholarly inquiry and the use, interpretation, and application of relevant research. CNSs use formal and informal coaching and teaching strategies with patients and families, nurses and nursing personnel, graduate nursing students, other clinical nurse specialists, health professionals, consumer groups, and organizations or systems (see Chapter 8). As health care systems are restructured, there is increasing emphasis on patients’ accountability for their own health. This means that in addition to coaching individuals, CNSs are even more likely to be involved in educational program planning and implementation aimed at helping groups of patients manage chronic illnesses and associated symptoms. Many patients know that they need to be better informed and educated about the health risk determinants, preventive self-care, treatment options, and risks and benefits of treatments, but their health care behaviors are influenced by many personal, psychological, and sociocultural factors. Because a patient is not always able or willing to change his or her lifestyle or to adhere to health care recommendations, a CNS must determine which patient or patient population is most appropriate for the advanced coaching requiring a CNS, such as a prenatal patient with poor social support living in an economically depressed community, an African American woman at risk of contracting human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), or a teenager who engages in risky behaviors. With many consumers seeking health care from nontraditional providers (Tindle, Davis, Phillips, et al., 2005), CNSs often help patients and providers integrate conventional and integrative therapies into care plans. A CNS is a role model for nurses, demonstrating the practical integration of theory and EBP. Whereas nurse practitioners (NPs) and certified nurse-midwives (CNMs) primarily coach patients and families, a CNS strives continuously to improve clinical practice and integrate new knowledge into practice, thereby influencing the further development of the proficient and expert nurse and enhancing the staff nurse’s accountability and self-sufficiency (Cronenwett, 2012). A CNS cannot be effective when she or he is or is perceived to be territorial, omnipotent, or omniscient (see Chapter 11). A CNS’s time is often better spent by teaching others the why, what, and how of common patient care interventions rather than repeatedly personally providing those same interventions. For example, a well-developed, standardized nursing care plan that details the assessment of different wound types and stages, with stage-specific interventions, will enable the nursing staff to provide consistent and evidence-based care to patients with the simpler types of wounds. The CNS is then appropriately consulted for complex wounds. Developing standards for patient education and providing resources to ensure consistency across populations are equally important CNS educational activities. As a staff nurse applies the new knowledge and skills taught by a CNS, the CNS can attend to new or more complex responsibilities. A staff nurse can become the role model for the skill mastered or the knowledge gained, and so a CNS’s influence will continue to improve patient care. This notion of extending the reach of the CNS’s expertise can be considered a defining characteristic of the coaching competency of CNS practice. The cycle of enrichment and growth is never complete. Whenever major staff turnover occurs or a CNS enters a new practice setting, the cycle must begin anew.

The Clinical Nurse Specialist

Overview and Definitions of the Clinical Nurse Specialist

Clinical Nurse Specialist Practice: Spheres of Influence and Advanced Practice Nursing Competencies

![]() TABLE 14-1

TABLE 14-1

Direct Clinical Practice

Guidance and Coaching

Patients and Families

Nurses and Nursing Personnel

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The Clinical Nurse Specialist

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access