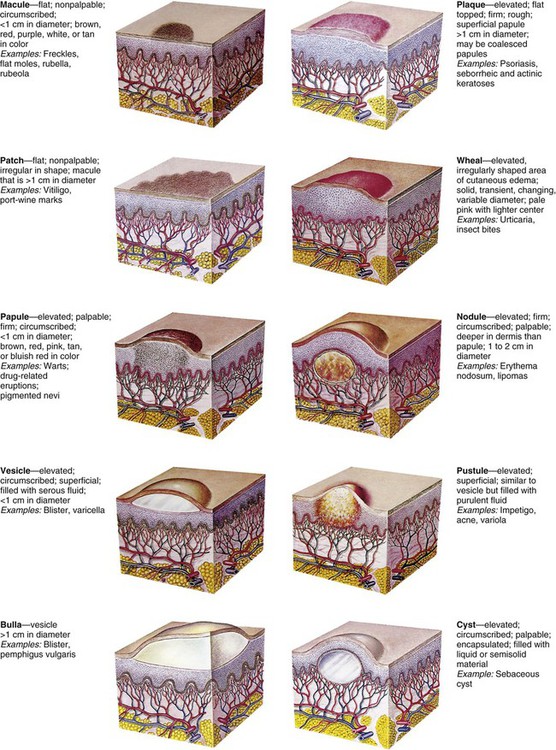

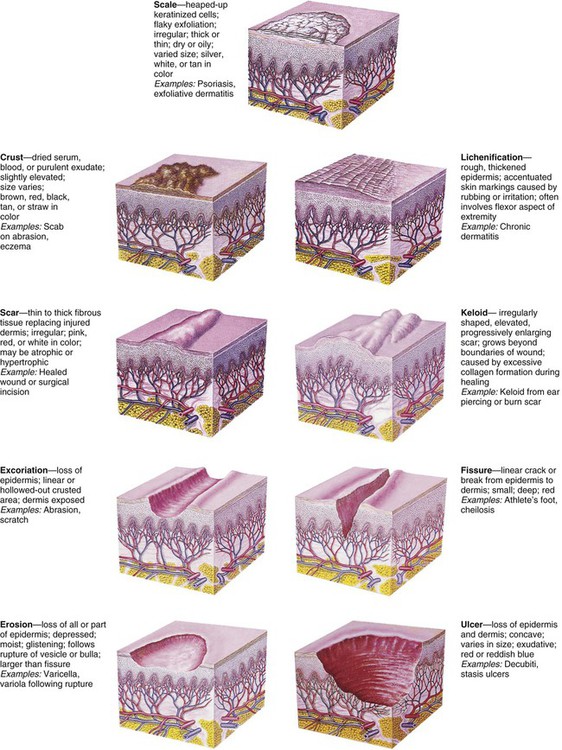

On completion of this chapter the reader will be able to: • Describe the distribution and configuration of various skin lesions. • List the benefits of a moist environment for wound healing. • Discuss the nursing care related to therapies for skin disorders. • Contrast the manifestations of and therapies for bacterial, viral, and fungal infections of the skin. • Compare the skin manifestations related to age in children. • Outline a care plan to prevent and treat diaper dermatitis. • Outline a care plan for a child with atopic dermatitis. • Formulate a teaching plan for an adolescent with acne. • Describe the methods for assessing a burn wound. • Discuss the physical and emotional care of a child with a severe burn wound. http://evolve.elsevier.com/wong/essentials Animations—Burns in Children; Tick Paralysis Case Studies—Acne Vulgaris; Burns; Impetigo; Poison Ivy; Tinea Capitis Nursing Care Plan—The Child with Burns: Management and Rehabilitative Stages Erythema—A reddened area caused by increased amounts of oxygenated blood in the dermal vasculature Ecchymoses (bruises)—Localized red or purple discolorations caused by extravasation of blood into dermis and subcutaneous tissues Petechiae—Pinpoint, tiny, and sharp circumscribed spots in the superficial layers of the epidermis Primary lesions—Skin changes produced by a causative factor; common primary lesions in pediatric skin disorders are macules, papules, and vesicles (Fig. 30-1) Secondary lesions—Changes that result from alteration in the primary lesions, such as those caused by rubbing, scratching, medication, or involution and healing (Fig. 30-2) Distribution pattern—The pattern in which lesions are distributed over the body, whether local or generalized, and the specific areas associated with the lesions Configuration and arrangement—The size, shape, and arrangement of a lesion or groups of lesions (e.g., discrete, clustered, diffuse, or confluent) When the skin is injured, its normal protective barrier function is broken. In a healthy immunocompetent individual, acute traumatic abrasions, lacerations, and superficial skin and soft tissue injuries heal spontaneously without complications. The process of tissue healing involves complex cellular interactions and biochemical reactions. The healing process is segregated into four phases that are characterized by the particular cells involved and the chemicals produced. The four stages of wound healing are hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling (Krasner, Rodeheaver, and Sibbald, 2007). Some authorities combine the first two phases. Numerous factors can delay healing (Table 30-1). For example, traditional practices, such as the use of antiseptics (hydrogen peroxide and povidone–iodine [Betadine] solutions), which were once thought to prevent infection, are now known to have a cytotoxic effect on healthy cells and minimal effect on controlling infections. Povidone–iodine may also be absorbed through the skin in neonates and young children. TABLE 30-1 FACTORS THAT DELAY WOUND HEALING DNA, Deoxyribonucleic acid; RBC, red blood cell; WBC, white blood cell. Some skin disorders demand aggressive therapy, but by and large, the major aim of treatment is to prevent further damage, eliminate the cause, prevent complications, and provide relief from discomfort while tissues undergo healing (McCord and Levy, 2006). Factors that contribute to the development of dermatitis and that prolong the course of the disease should be eliminated when possible. The most common causative agents of dermatitis in infants, children, and adolescents are environmental factors (soaps, bubble baths, shampoos, rough or tight clothing, wet diapers, blankets, and toys) and the natural elements (e.g., dirt, sand, heat, cold, moisture, and wind). Dermatitis may also result from home remedies and medications.

The Child with Integumentary Dysfunction

Integumentary Dysfunction

Skin Lesions

Diagnostic Evaluation

Types of Lesions

Wounds

Process of Wound Healing

Factors That Influence Healing

FACTOR

EFFECT ON HEALING

Dry wound environment

Allows epithelial cells to dry out and die; impairs migration of epithelial cells across wound surface

Nutritional deficiencies

Vitamin A

Results in inadequate inflammatory response

Vitamin B1

Results in decreased collagen formation

Vitamin C

Inhibits formation of collagen fibers and capillary development

Protein

Reduces supply of amino acids for tissue repair

Zinc

Impairs epithelialization

Immunocompromise

Results in inadequate or delayed inflammatory response

Impaired circulation

Inhibits inflammatory response and removal of debris from wound area

Reduces supply of nutrients to wound area

Stress (pain, poor sleep)

Releases catecholamines that cause vasoconstriction

Antiseptics

Hydrogen peroxide

Toxic to fibroblasts; can cause subcutaneous gas formation (mimics gas-forming infection)

Povidone–iodine

Toxic to WBCs, RBCs, and fibroblasts

Chlorhexidine

Toxic to WBCs

Medications

Corticosteroids

Impair phagocytosis

Inhibit fibroblast proliferation

Depress formation of granulation tissue

Inhibit wound contraction

Chemotherapy

Interrupts the cell cycle; damages DNA or prevents DNA repair

Antiinflammatory drugs

Decrease the inflammatory phase

Foreign bodies

Increase inflammatory response

Inhibit wound closure

Infection

Increases inflammatory response

Increases tissue destruction

Mechanical friction

Damages or destroys granulation tissue

Fluid accumulation

Accumulation in area inhibits tissues from approximating

Radiation

Inhibits fibroblastic activity and capillary formation

May cause tissue necrosis

Diseases

Diabetes mellitus

Inhibits collagen synthesis

Impairs circulation and capillary growth

Hyperglycemia impairs phagocytosis

Anemia

Reduces oxygen supply to tissues

Peripheral vascular disease

Reduces oxygen supply to wounds

Uremia

Decreases collagen and granulation tissue

General Therapeutic Management