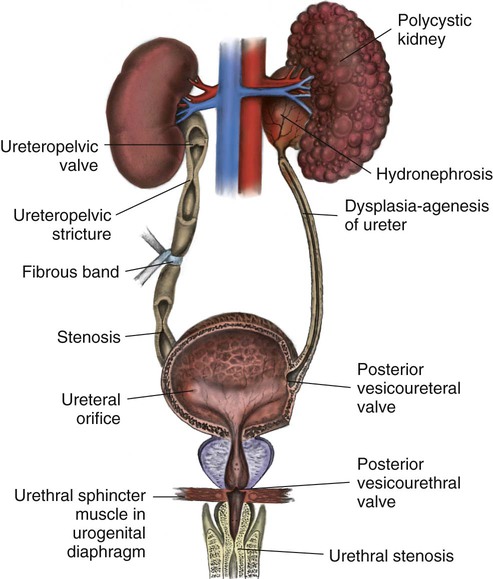

On completion of this chapter the reader will be able to: • Describe the various factors that contribute to urinary tract infections in infants and children. • Discuss the preoperative preparation of the child and parents when the child has a structural defect of the genitourinary tract. • Demonstrate an understanding of the causes and mechanisms of edema formation in nephrotic syndrome. • Outline a nursing care plan for a child with nephrotic syndrome. • Compare the child with minimal-change nephrotic syndrome and the child with acute glomerulonephritis in terms of clinical manifestations and nursing care. • Contrast the causes, complications, and management of acute and chronic renal failure. • List the types of renal dialysis. http://evolve.elsevier.com/wong/essentials Animations—Bladder; Kidney Function Case Studies—Acute Renal Failure; Urinary Tract Infection Nursing Care Plans—The Child with Acute Renal Dysfunction; The Child with Nephrotic Syndrome Many of the clinical manifestations of renal disease are common to a variety of childhood disorders, but their presence is an indication to obtain further information from the child’s history, family history, and laboratory studies as part of a complete physical examination. Suspected renal disease can be further evaluated by means of radiographic studies and renal biopsy (Table 27-1). TABLE 27-1 RADIOLOGIC AND OTHER TESTS OF URINARY SYSTEM FUNCTION Both urine and blood studies contribute vital information for detection of renal problems. The single most important test is probably routine urinalysis. Specific urine and blood tests provide additional information. Because nurses are usually the persons who collect the specimens for examination and who often perform many of the screening tests, they should be familiar with the test, its function, and factors that can alter or distort the results of the test. The major urine and blood tests are outlined in Tables 27-2 and 27-3. TABLE 27-2 TABLE 27-3 The nurse is generally the one who is responsible for preparing infants, children, and parents for tests and for collection of urine and (sometimes) blood specimens for observation and laboratory analysis (see Preparation for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Procedures, and Collection of Specimens, Chapter 22). An important nursing responsibility is to maintain careful intake and output measurements and blood pressure for most children with genitourinary dysfunction and those who might be at risk for developing renal complications (e.g., children in shock, postoperative patients). For example, any significant degree of renal disease can diminish the glomerular filtration rate (GFR), a measure of the amount of plasma from which a given substance is totally cleared in 1 minute. A number of substances can be used, but the most useful clinical estimation of glomerular filtration is the clearance of creatinine, an end product of protein metabolism in muscle and a substance that is freely filtered by the glomerulus and secreted by renal tubular cells. The nurse’s responsibility in this test is collection of urine, usually a 12- or 24-hour specimen. Bacteriuria—Presence of bacteria in the urine Asymptomatic bacteriuria—Significant bacteriuria (usually defined as >100,000 colony-forming units [CFUs]) with no evidence of clinical infection Symptomatic bacteriuria—Bacteriuria accompanied by physical signs of UTI (dysuria, suprapubic discomfort, hematuria, fever) Recurrent UTI—Repeated episode of bacteriuria or symptomatic UTI Persistent UTI—Persistence of bacteriuria despite antibiotic treatment Febrile UTI—Bacteriuria accompanied by fever and other physical signs of UTI; presence of a fever typically implies pyelonephritis Cystitis—Inflammation of the bladder Urethritis—Inflammation of the urethra Pyelonephritis—Inflammation of the upper urinary tract and kidneys Urosepsis—Febrile UTI coexisting with systemic signs of bacterial illness; blood culture reveals presence of urinary pathogen The structure of the lower urinary tract is believed to account for the increased incidence of bacteriuria in females (Rosenthal, 2004). The short urethra, which measures about 2 cm (0.75 inch) in young girls and 4 cm (1.6 inches) in mature women, provides a ready pathway for invasion of organisms. In addition, the closure of the urethra at the end of micturition may return contaminated bacteria to the bladder. The longer male urethra (as long as 20 cm [8 inches] in an adult) and the antibacterial properties of prostatic secretions inhibit the entry and growth of pathogens. The single most important host factor influencing the occurrence of UTI is urinary stasis. Ordinarily, urine is sterile, but at 37° C (98.6° F), it provides an excellent culture medium. Under normal conditions, the act of completely and repeatedly emptying the bladder flushes away any organisms before they have an opportunity to multiply and invade surrounding tissue. However, urine that remains in the bladder allows bacteria from the urethra to rapidly become established in the rich medium. Incomplete bladder emptying (stasis) may result from reflux (see Vesicoureteral Reflux, p. 909), anatomic abnormalities (especially those involving the ureters), dysfunction of the voiding mechanism, or extrinsic ureteral or bladder compression that may be caused by constipation. The key to preventing UTI is to maintain adequate blood supply to the bladder wall by avoidance of overdistention and high bladder pressure. Most pathogens favor an alkaline medium. Normally, urine is slightly acidic with a median pH of 6. A urine pH of about 5 hampers but does not eliminate bacterial multiplication. Much has been reported about the use of cranberry products to increase urine acidity in an effort to prevent UTI. Recent review of the literature in adult subjects supports the use of cranberry products in reducing the incidence of UTI in women (Jepson, Mihaljevic, and Craig, 2008). Results of one study in children suggests that daily consumption of concentrated cranberry juice can prevent recurrence of symptomatic UTIs (Ferrara, Romaniello, Vitelli, and others, 2009). Further research that controls for type of cranberry product used, dosing regimens, and patient selection based on age and underlying medical condition is required to clarify unanswered questions before recommendations can be made regarding the use of this supplement, especially in the pediatric population. The clinical manifestations of UTI depend on the child’s age (Box 27-1). Diagnosis of UTI is confirmed by detection of bacteriuria in urine culture, but urine collection is often difficult, especially in infants and very small children. Several factors may alter a urine specimen, and contamination of a specimen by organisms from sources other than the urine, such as perineal and perianal flora in bag specimens, is the most frequent cause of false-positive results. Unless the specimen is a first morning sample, a recent high fluid intake may indicate a falsely low organism count. Therefore, children should not be encouraged to drink large volumes of water in an attempt to obtain a specimen quickly. For children with mild to moderate reflux, a minimally invasive endoscopic option (subtrigonal injection or STING) is an alternative to daily antibiotics or open surgical intervention. A bulking agent—dextranomer–hyaluronic acid polymer (Deflux)—is injected into the mucous membrane of the ureter, making retrograde flow of urine more difficult. Overall cure rates relate to degree of reflux and range from 67.4% to 88.3%, although more than one injection may be needed to achieve resolution (Chen, Yeh, and Chou, 2010). Frequently, additional tests are performed to detect anatomic defects. Children are prepared for these tests as appropriate for their age. This includes an explanation of the procedure, its purpose, and what the children will experience (see Preparation for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Procedures, Chapter 22). Sometimes a simple description of the urinary system is helpful. Especially for preschool children, the nurse must clarify that the urinary tract is separate from any sexual function and that the test is for a problem that they did not cause. Children may associate blame for perceived wrongdoing (e.g., masturbation) or unacceptable thoughts with the reason for the illness or the tests. For children younger than 3 to 4 years of age, the procedure can be explained on a doll. For those who are older, a simple drawing of the bladder, urethra, ureters, and kidneys makes the procedure more understandable. Obstruction may be congenital or acquired, unilateral or bilateral, and complete or incomplete with acute or chronic manifestations. The obstruction can occur at any level of the upper or lower urinary tract (Fig. 27-2). Partial obstruction may not be symptomatic unless there is a water or solute diuresis. Boys are affected more frequently than girls, and malformations should be suspected when patients have some other congenital defects (e.g., prune belly syndrome, chromosomal anomalies, anorectal malformations, defects of the pinna of the ear). Nursing goals in urinary tract obstruction include helping to identify cases, assisting with diagnostic procedures, and caring for children with complications (described elsewhere). Preparing parents and children for procedures is a major nursing responsibility. Preparation for urinary diversion procedures is of special importance (see Preparation for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Procedures, Chapter 22). Defects of the external genitourinary tract are serious conditions primarily because of the psychologic impact on the child. Satisfactory surgical repair is successful for the more common disorders and is carried out or initiated as early as possible. The major anomalies of the lower genitourinary tract, their description, and their management are outlined in Table 27-4. TABLE 27-4 DEFECTS OF THE GENITOURINARY TRACT

The Child with Genitourinary Dysfunction

Genitourinary Dysfunction

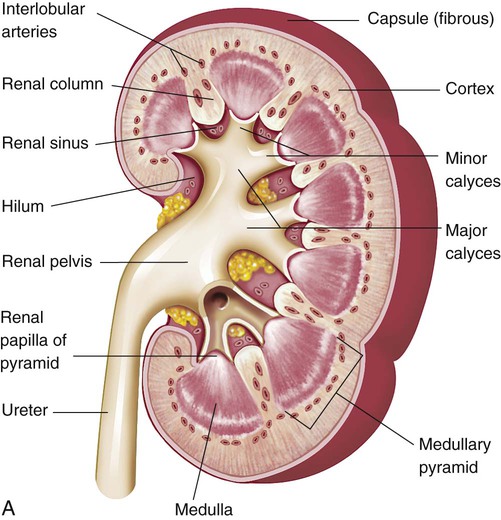

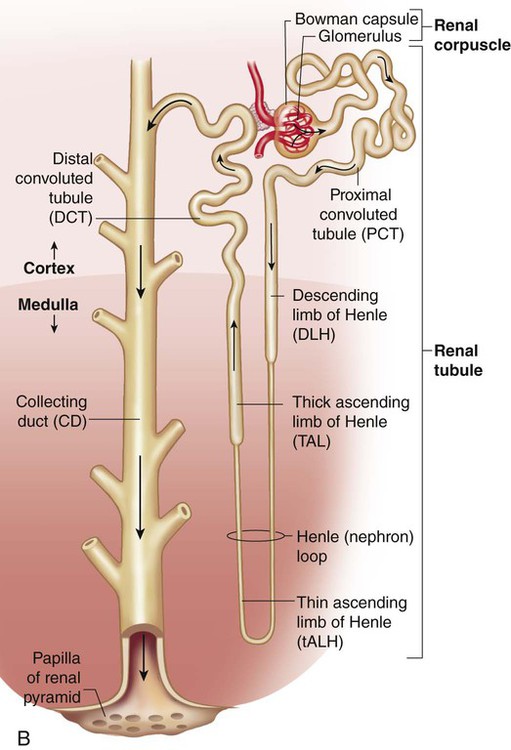

![]() Assessment of kidney and urinary tract integrity and diagnosis of renal or urinary tract disease are based on several evaluative tools. Physical examination, history taking, and observation of symptoms are the initial procedures. In suspected urinary tract diseases or disorders, further assessment by laboratory, radiologic, and other evaluative methods is carried out. Figure 27-1 provides a review of the kidney and nephron structures.

Assessment of kidney and urinary tract integrity and diagnosis of renal or urinary tract disease are based on several evaluative tools. Physical examination, history taking, and observation of symptoms are the initial procedures. In suspected urinary tract diseases or disorders, further assessment by laboratory, radiologic, and other evaluative methods is carried out. Figure 27-1 provides a review of the kidney and nephron structures.

Clinical Manifestations

TEST

PROCEDURE

PURPOSE

COMMENTS AND NURSING RESPONSIBILITIES

Urine culture and sensitivity

Collection of sterile specimen

Determines presence of pathogens and the drugs to which they are sensitive

Does not require specific parental permission

Send specimen to laboratory immediately after collection

Catheterization, clean-catch, or suprapubic specimen

Renal and bladder ultrasonography

Transmission of ultrasonic waves through renal parenchyma, along ureteral course, and over bladder

Allows visualization of renal parenchyma and renal pelvis without exposure to external-beam radiation or radioactive isotopes

Visualization of dilated ureters and bladder wall also possible

Noninvasive procedure

Testicular (scrotal) ultrasonography

Transmission of ultrasonic waves through scrotal contents and testis

Allows visualization of scrotal contents, including testis

Testicular ultrasonography is used to identify masses, and Doppler-enhanced ultrasonography is used to differentiate hyperemia of epididymo-orchitis from ischemia or torsion

Noninvasive procedure

Scout film

Flat plate radiograph of abdomen and pelvis for KUB

Detects and establishes renal outlines, presence of calculi, or opaque foreign bodies in bladder

Prepare as for routine x-ray film

Voiding cystourethrography

Contrast medium injected into bladder through urethral catheter until bladder is full; films taken before, during, and after voiding

Visualizes bladder outline and urethra, reveals reflux of urine into ureters, and shows complications of bladder emptying

Prepare child for catheterization

Radionuclide (nuclear) cystogram

Radionuclide-containing fluid injected through urethral catheter until bladder is full; images generated before, during, and after voiding

Alternative to voiding cystourethrography in children with allergy to intravesical contrast material

Allows evaluation of reflux, although visualization of anatomic details is relatively poor

Prepare child for catheterization

Reassure patient and parents that allergic response to contrast materials is avoided by use of radionuclide

Radioisotope imaging studies

Contrast medium injected intravenously; computer analysis to measure uptake or washout (excretion) for analysis of organ function

DTPA radioisotope used to measure GFR; estimate of differential renal function and renal washout to determine presence and location of upper urinary tract obstruction

DMSA radioisotope used to visualize renal scars and differential renal function; does not visualize ureters and bladder

MAG3 radioisotope combines features of DTPA (evaluation of upper urinary tract obstruction) with features of DMSA radioisotope (differential renal function)

Insert or assist with insertion of IV infusion

Monitor IV infusion

Urethral catheterization may accompany DTPA radioisotope scan; prepare child for catheterization when indicated

IVP (IV urography; excretory urography)

IV injection of a contrast medium

Medium secreted and concentrated by tubules

X-ray films made 5, 10, and 15 minutes after injection; delayed films (30, 60 minutes, and so on) are obtained if obstruction suspected

Defines urinary tract

Provides information about integrity of kidneys, ureters, and bladder

Retroperitoneal masses visualized when they shift position of ureters

Preparation for test:

Infants up to 2 years of age—no solid food; omit one bottle on morning of examination; perform studies early to avoid withholding of fluids

Children ages 2–14 years—give cathartic evening before examination, nothing orally after midnight, enema (soapsuds) morning of examination

CT

Narrow-beam x-rays and computer analysis provide precise reconstruction of area

Visualizes vertical or horizontal cross section of kidney

Especially valuable to distinguish tumors and cysts

Noncontrast scan is noninvasive

Contrast-enhanced CT scan preparation similar to that for IVP

Cystoscopy

Direct visualization of bladder and lower urinary tract through small scope inserted via urethra

Investigation of bladder and lower tract lesions; visualizes ureteral openings, bladder wall, trigone, and urethra

Give nothing orally after midnight

Carry out preoperative preparations

Prepare the child for cystoscopy

Retrograde pyelography

Contrast medium injected through ureteral catheter

Visualizes pelvic calyces, ureters, and bladder

Give cathartic if ordered

Give preoperative medication if ordered

Observe for reaction to contrast medium

Monitor vital signs after procedure

Renal angiography

Contrast medium injected directly into renal artery via catheter placed in femoral artery (or umbilical artery in newborn) and advanced to renal artery

Visualizes renal vascular system, especially for renal arterial stenosis

Prepare child for insertion of a spinal needle or perfusion catheter in renal pelvis (anesthetic often required)

Whitaker perfusion test

Injection of contrast material through renal pelvis and ureters

Measures pressures in renal pelvis and urinary bladder

Determine presence of obstruction causing upper urinary tract dilation

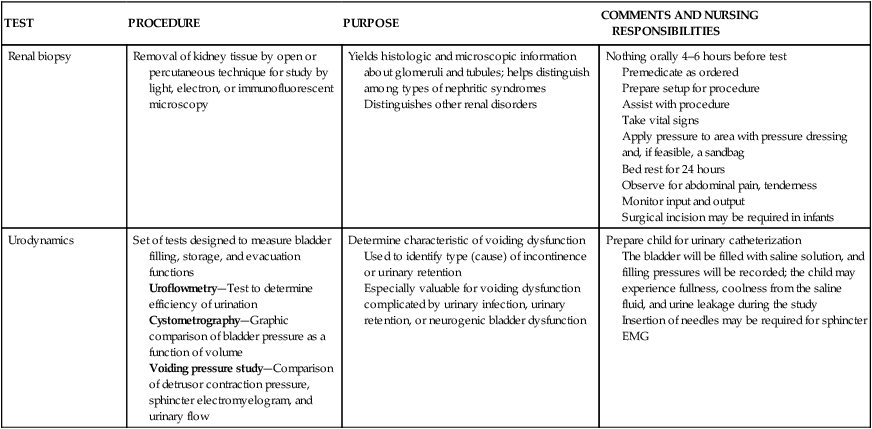

Renal biopsy

Removal of kidney tissue by open or percutaneous technique for study by light, electron, or immunofluorescent microscopy

Yields histologic and microscopic information about glomeruli and tubules; helps distinguish among types of nephritic syndromes

Distinguishes other renal disorders

Nothing orally 4–6 hours before test

Premedicate as ordered

Prepare setup for procedure

Assist with procedure

Take vital signs

Apply pressure to area with pressure dressing and, if feasible, a sandbag

Bed rest for 24 hours

Observe for abdominal pain, tenderness

Monitor input and output

Surgical incision may be required in infants

Urodynamics

Set of tests designed to measure bladder filling, storage, and evacuation functions

Uroflowmetry—Test to determine efficiency of urination

Cystometrography—Graphic comparison of bladder pressure as a function of volume

Voiding pressure study—Comparison of detrusor contraction pressure, sphincter electromyelogram, and urinary flow

Determine characteristic of voiding dysfunction

Used to identify type (cause) of incontinence or urinary retention

Especially valuable for voiding dysfunction complicated by urinary infection, urinary retention, or neurogenic bladder dysfunction

Prepare child for urinary catheterization

The bladder will be filled with saline solution, and filling pressures will be recorded; the child may experience fullness, coolness from the saline fluid, and urine leakage during the study

Insertion of needles may be required for sphincter EMG

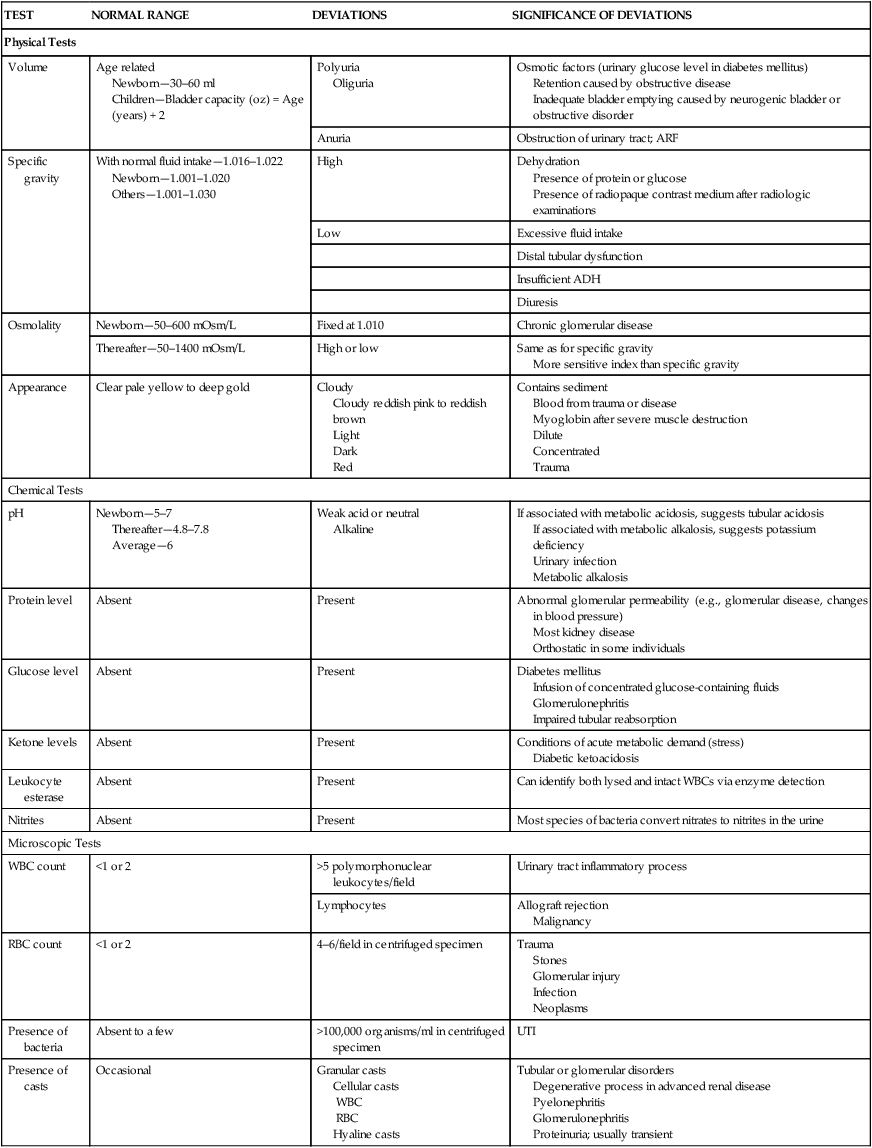

Laboratory Tests

TEST

NORMAL RANGE

DEVIATIONS

SIGNIFICANCE OF DEVIATIONS

Physical Tests

Volume

Age related

Newborn—30–60 ml

Children—Bladder capacity (oz) = Age (years) + 2

Polyuria

Oliguria

Osmotic factors (urinary glucose level in diabetes mellitus)

Retention caused by obstructive disease

Inadequate bladder emptying caused by neurogenic bladder or obstructive disorder

Anuria

Obstruction of urinary tract; ARF

Specific gravity

With normal fluid intake—1.016–1.022

Newborn—1.001–1.020

Others—1.001–1.030

High

Dehydration

Presence of protein or glucose

Presence of radiopaque contrast medium after radiologic examinations

Low

Excessive fluid intake

Distal tubular dysfunction

Insufficient ADH

Diuresis

Osmolality

Newborn—50–600 mOsm/L

Fixed at 1.010

Chronic glomerular disease

Thereafter—50–1400 mOsm/L

High or low

Same as for specific gravity

More sensitive index than specific gravity

Appearance

Clear pale yellow to deep gold

Cloudy

Cloudy reddish pink to reddish brown

Light

Dark

Red

Contains sediment

Blood from trauma or disease

Myoglobin after severe muscle destruction

Dilute

Concentrated

Trauma

Chemical Tests

pH

Newborn—5–7

Thereafter—4.8–7.8

Average—6

Weak acid or neutral

Alkaline

If associated with metabolic acidosis, suggests tubular acidosis

If associated with metabolic alkalosis, suggests potassium deficiency

Urinary infection

Metabolic alkalosis

Protein level

Absent

Present

Abnormal glomerular permeability (e.g., glomerular disease, changes in blood pressure)

Most kidney disease

Orthostatic in some individuals

Glucose level

Absent

Present

Diabetes mellitus

Infusion of concentrated glucose-containing fluids

Glomerulonephritis

Impaired tubular reabsorption

Ketone levels

Absent

Present

Conditions of acute metabolic demand (stress)

Diabetic ketoacidosis

Leukocyte esterase

Absent

Present

Can identify both lysed and intact WBCs via enzyme detection

Nitrites

Absent

Present

Most species of bacteria convert nitrates to nitrites in the urine

Microscopic Tests

WBC count

<1 or 2

>5 polymorphonuclear leukocytes/field

Urinary tract inflammatory process

Lymphocytes

Allograft rejection

Malignancy

RBC count

<1 or 2

4–6/field in centrifuged specimen

Trauma

Stones

Glomerular injury

Infection

Neoplasms

Presence of bacteria

Absent to a few

>100,000 organisms/ml in centrifuged specimen

UTI

Presence of casts

Occasional

Granular casts

Cellular casts

WBC

RBC

Hyaline casts

Tubular or glomerular disorders

Degenerative process in advanced renal disease

Pyelonephritis

Glomerulonephritis

Proteinuria; usually transient

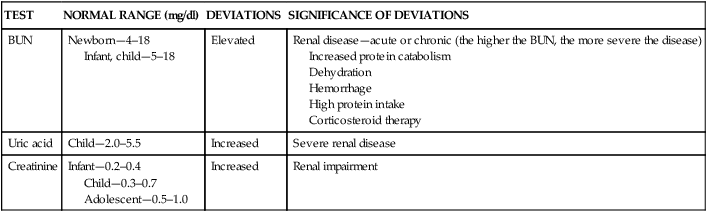

TEST

NORMAL RANGE (mg/dl)

DEVIATIONS

SIGNIFICANCE OF DEVIATIONS

BUN

Newborn—4–18

Infant, child—5–18

Elevated

Renal disease—acute or chronic (the higher the BUN, the more severe the disease)

Increased protein catabolism

Dehydration

Hemorrhage

High protein intake

Corticosteroid therapy

Uric acid

Child—2.0–5.5

Increased

Severe renal disease

Creatinine

Infant—0.2–0.4

Child—0.3–0.7

Adolescent—0.5–1.0

Increased

Renal impairment

Nursing Care Management

Genitourinary Tract Disorders and Defects

Urinary Tract Infection

![]() Case Study—Urinary Tract Infection

Case Study—Urinary Tract Infection

![]() Infection of the genitourinary tract is one of the most common conditions of childhood. Up to 10% of children will have a febrile urinary tract infection (UTI) during the first 2 years of life (Kanellopoulos, Salakos, Spiliopoulou, and others, 2006). Among febrile boys, circumcision status is important in determining the risk for UTI. Uncircumcised male infants younger than 3 months of age had the highest prevalence of UTI (20.1%) of any group, male or female (Shaikh, Morone, Bost, and others, 2008). Circumcision status should be assessed in male infants with unexplained fever. UTI may involve the urethra and bladder (lower urinary tract) or the ureters, renal pelvis, calyces, and renal parenchyma (upper urinary tract). Because it is often impossible to localize the infection, the broad designation UTI is applied to the presence of significant numbers of microorganisms anywhere within the urinary tract except the distal third of the urethra, which is usually colonized with bacteria.

Infection of the genitourinary tract is one of the most common conditions of childhood. Up to 10% of children will have a febrile urinary tract infection (UTI) during the first 2 years of life (Kanellopoulos, Salakos, Spiliopoulou, and others, 2006). Among febrile boys, circumcision status is important in determining the risk for UTI. Uncircumcised male infants younger than 3 months of age had the highest prevalence of UTI (20.1%) of any group, male or female (Shaikh, Morone, Bost, and others, 2008). Circumcision status should be assessed in male infants with unexplained fever. UTI may involve the urethra and bladder (lower urinary tract) or the ureters, renal pelvis, calyces, and renal parenchyma (upper urinary tract). Because it is often impossible to localize the infection, the broad designation UTI is applied to the presence of significant numbers of microorganisms anywhere within the urinary tract except the distal third of the urethra, which is usually colonized with bacteria.

Classification

Etiology

Anatomic and Physical Factors

Altered Urine and Bladder Chemistry

Diagnostic Evaluation

Therapeutic Management

Vesicoureteral Reflux

Nursing Care Management

Obstructive Uropathy

Nursing Care Management

External Defects

DEFECT

THERAPEUTIC MANAGEMENT

Inguinal hernia—Protrusion of abdominal contents through inguinal canal into scrotum

Detected as painless inguinal swelling of variable size

Surgical closure of inguinal defect

Hydrocele—Fluid in scrotum

Surgical repair indicated if spontaneous resolution not accomplished in 1 year

Phimosis—Narrowing or stenosis of preputial opening of foreskin

Mild cases—Manual retraction of foreskin and proper cleansing of area

Severe cases—Circumcision or vertical division and transverse suturing of foreskin

Hypospadias—Urethral opening located behind glans penis or anywhere along ventral surface of penile shaft

Objectives of surgical correction:

Enable child to void in standing position and direct stream voluntarily in usual manner

Improve physical appearance of genitalia

Produce a sexually adequate organ

Chordee—Ventral curvature of penis, often associated with hypospadias

Surgical release of fibrous band causing the deformity

Epispadias—Meatal opening located on dorsal surface of penis

Surgical correction, usually including penile and urethral lengthening and bladder neck reconstruction (if necessary)

Cryptorchidism—Failure of one or both testes to descend normally through inguinal canal

Detected by inability to palpate testes within scrotum

Medical—Administration of human chorionic gonadotropin (older child)

Surgical—Orchiopexy

Objectives of therapy:

Prevent damage to undescended testicle

Decrease incidence of malignant tumor formation

Avoid trauma and torsion

Close inguinal canal

Prevent cosmetic and psychologic disability from empty scrotum

Exstrophy of bladder—Eversion of posterior bladder through anterior bladder wall and lower abdominal wall; associated with open pubic arch (a severe defect)

Potential objectives of surgical correction:

Preserve renal function

Attain urinary control

Provide adequate reconstructive repair

Improve sexual function (especially in males)

Disorders of Sexual Differentiation

Masculinized female (female pseudohermaphrodite)

Assign gender as female; assign gender while avoiding irreversible surgery, realizing some children may change gender later in life; family participation essential

Incompletely masculinized male (male pseudohermaphrodite)

Assign gender while avoiding irreversible surgery, realizing some children may change gender later in life; family participation essential

True hermaphrodite (both ovaries and testes)

Assign gender while avoiding irreversible surgery, realizing some children may change gender later in life; gender assignment depends on predominant characteristics; family participation essential

Mixed gonadal dysgenesis

Assign gender while avoiding irreversible surgery, realizing some children may change gender later in life; gender assignment depends on predominant characteristics; family participation essential ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The Child with Genitourinary Dysfunction

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access