The Child with an Immunologic Alteration

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

• Explain how neonates acquire active and passive immunity.

• Delineate how to prevent the spread of organisms in children with an immune deficiency.

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/James/ncoc

Immunologic alterations typically are chronic, lasting from months to years and interfering with a child’s life. Physical signs range from simple, such as impaired skin integrity, to complex, such as overwhelming infection. Intervals of wellness, relapses, and sometimes a decline in health should be expected. Repeated office visits and hospitalizations, disruptions in family routines, altered social interactions, and emotional and financial strain often are coupled with anxiety about the future.

Initially, the nurse helps the family adjust to a new, often devastating diagnosis. Care during the acute phase of the illness may be critical in nature, as underlying organisms are diagnosed and treated and fevers and pain are controlled. Once the acute crisis has resolved, the nurse prepares the family for discharge by teaching home management and identifying community resources and referrals for continuing support. The nurse also teaches the family how to prevent the spread of microorganisms through infection control practices at home and describes parameters for when to call the health provider. The nurse discusses ways to maintain the child’s skin integrity, the body’s first line of protection against microorganisms, and recommends a diet that supports immune cell growth. The nurse must keep abreast of current information because the field of immunology continues to evolve. Nurses also play a vital role in advocating for children with conditions such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

Despite all efforts, rehospitalization is often inevitable. The family is an integral part of the multidisciplinary team, keeping the physicians, nurses, and social workers informed of changes in the child’s condition, administering medications, providing respiratory care, and often making difficult decisions about continued treatment and comfort.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection

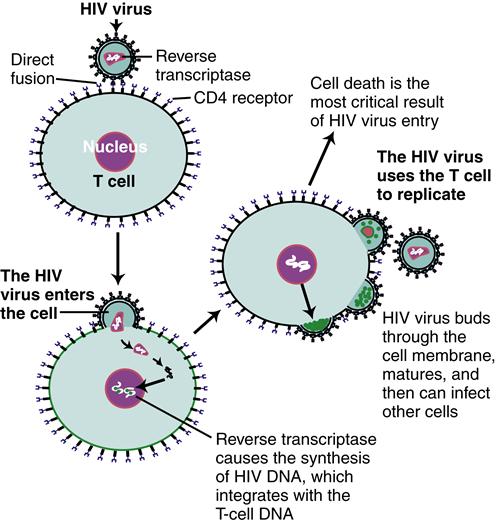

HIV infection is an acquired cell-mediated immunodeficiency disorder that causes a wide spectrum of manifestations in children, ranging from no signs or symptoms to mild and moderate to severe signs and symptoms. Because of improved medical approaches to this condition, HIV infection is viewed as a chronic condition with ongoing challenges. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is the most advanced manifestation of this infection.

Etiology

HIV, present in an infected individual’s blood or body fluids, can enter an uninfected adult’s or adolescent’s body in several ways, including sharing of needles or syringes, engaging in unprotected sexual activity with an infected person where body fluids are shared, or receiving an infected blood product. Infected women can transmit the virus to a fetus across the placenta during pregnancy, to the infant at delivery, and to the young child through breastfeeding. Since 1994, when it became practice to administer zidovudine (ZDV) to mothers prenatally and intrapartally and to the newborn infant, the incidence of perinatal transmission has decreased markedly (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010). Increases in prenatal counseling and testing and a combination antiretroviral regimen during pregnancy, combined with specific obstetric interventions designed to prevent transmission during labor, have reduced the transmission risk to less than 2% (CDC, 2010). The risk of children acquiring HIV infection through sexual abuse still exists.

Incidence

The incidence of HIV infection in infants and children in the United States is approximately 200 children annually, and this

has been stable for several years (CDC, 2009a). Ninety-one percent of cases of HIV infection are the result of perinatal transmission (CDC, 2010). In the United States, more than 10,000 children younger than 19 years of age are living with HIV/AIDS (CDC, 2009a). This brings challenges for children, families, and health professionals alike.

Heterosexual intimacy and infection through intravenous (IV) drug use are the most common transmission modes of HIV for women and adolescent girls. In the United States, African-American children younger than age 13 years are disproportionately affected, followed by Hispanic children (CDC, 2009a).

Manifestations

Box 42-1 lists findings associated with general immunodeficiency. Children with HIV manifest most or all of these signs. HIV infection in children and adults differs in several ways (Working Group on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children, 2008; Yogev & Chadwick, 2011):

The CDC classifies the clinical manifestations of HIV infection as not symptomatic (category N), mildly symptomatic (category A), moderately symptomatic (category B), or severely symptomatic (category C) in children younger than 13 years (Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children, 2011). Mild signs of the illness may be nonspecific and include lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, dermatitis, parotitis, and recurrent or persistent upper respiratory infection, sinusitis, or otitis media. In moderate disease, some signs are considered to be important if they persist or recur, particularly anemia, neutropenia, or thrombocytopenia; diarrhea; fever for longer than 1 month; herpes simplex; and oral candidiasis in children older than 6 months. Other signs of moderate infection include bacterial meningitis, pneumonia, or sepsis (one episode); cardiomyopathy; complicated chickenpox; herpes zoster; hepatitis; nephropathy; LIP; and toxoplasmosis onset before age 1 month (Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children, 2011, pp. 32-33). In general, in addition to LIP the most common indicators of AIDS in children younger than 13 years are serious confirmed bacterial infections (multiple or recurrent), PCP and other opportunistic infections, encephalopathy, lymphomas and Kaposi sarcoma, and severe nutritional deficits with fall-off on growth percentiles (wasting syndrome) without evidence of being caused by another disease process (Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children, 2011).

Diagnostic Evaluation

Because most HIV infections in infants and children occur as a result of perinatal transmission, HIV-positive pregnant women must be identified, educated, and treated. Early identification and treatment of women reduce the HIV transmission rate and enable early diagnosis and treatment for infected infants. Recommendations for preventing HIV transmission to neonates now includes universal testing of all pregnant women (unless they “opt out”) and HIV counseling. Women who are found to be at risk for HIV are tested a second time at 36 weeks’ gestation. If a woman does not receive HIV counseling and treatment during pregnancy, counseling and treatment as soon as possible after delivery facilitates optimal management of the newborn (Panel on Treatment of HIV-Infected Pregnant Women and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission, 2010).

Diagnosing HIV-Exposed Infants

Diagnosing HIV through traditional HIV antibody measurement by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or Western blot assay is not accurate for a positive or negative diagnosis in infants younger than 18 months because of the presence of maternal antibodies. Instead, virologic assay tests are used. These include HIV deoxyribonucleic acid polymerase chain reaction (DNA PCR) or HIV ribonucleic acid (RNA) assay.

For infants who have been exposed to HIV, virologic testing is performed when the infant is 14 to 21 days old, at 1 to 2 months, and again at 4 to 6 months; health care providers should consider performing virologic studies immediately after birth for infants known to be at risk for exposure (Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children, 2011).

Two positive virologic assays obtained on two separate occasions establish a positive diagnosis. Two negative virologic assays from separate specimens taken at 1 month of age and older and again at 4 months of age and older in nonbreastfed infants can establish negative HIV status; some specialists will follow up with an antibody test between 12 and 18 months of age to confirm (Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children, 2011). Two negative HIV antibody tests from separate specimens can rule out HIV infection in a child older than 6 months. HIV antibody measurement may be used if the child is older than 18 months. For all these tests, infants must not show any clinical signs of HIV infection (Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children, 2011).

Ongoing Diagnostic Monitoring

CD4+ lymphocyte counts and HIV RNA assays assess an infected young child’s immune status, response to therapy, risk for disease progression, and need for PCP prophylaxis after 1 year of age. Low CD4+ counts or decreased percentage indicate reduced immune function. CD4+ counts are measured at diagnosis and every 3 to 4 months thereafter, except in adolescents who have stable immune function; counts in stable and medication-adherent adolescents can be done less frequently. Monitoring may occur more often for infants younger than 12 months old, when a deterioration in physical condition is suspected, and when making decisions to treat or change treatment (Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children, 2011). Although the CD4+ lymphocyte counts vary by age in children younger than 5 years old, the CD4+ cell percentage does not, and so the percentage is considered to be a more accurate assessment for childhood disease progression in children of this age-group (Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children, 2011).

The amount of virus in peripheral blood is called the viral burden. The HIV viral burden is measured by plasma HIV RNA copy number and is determined by use of a quantitative HIV RNA assay. The HIV RNA copy numbers work in tandem with the CD4+ percentage to provide independent information about prognosis and guide treatment decisions. HIV RNA copy number is assessed immediately after positive virologic diagnosis of HIV and every 3 to 4 months subsequently, or more often, depending on the child’s clinical and treatment status (Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children, 2011). Infants who are infected perinatally initially have a high viral burden; this burden decreases gradually over several years. A high viral burden (>299,000 copies/mL) in infants younger than 12 months of age may be related to more rapid disease progression (Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children, 2011).

Therapeutic Management

The goals of management are directed toward rapidly decreasing the viral load to below detectable levels with the lowest risk of drug toxicity, preserving immune function, facilitating normal growth and development, and preventing medication resistance (Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children, 2011). Viral suppression that is ineffective can result in medication resistance, so a dosage schedule that is the least complex to manage, while providing maximum benefit with fewest toxic effects, results in improved adherence to a medication regimen.

If a mother’s HIV status is unknown when she begins labor, HIV antibody testing should be done and her infant treated as if there were a known HIV exposure. If maternal antibody test results are negative, treatment for the infant may be discontinued (Panel on Treatment of HIV-Infected Pregnant Women and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission, 2010).

HIV-Exposed Infants

In addition to giving IV ZDV to the mother during labor, all infants of known HIV-positive mothers should receive oral ZDV therapy within 6 to 12 hours after birth. This should continue for 6 weeks or until the infant is positively diagnosed with HIV, at which time the regimen is changed to a combination of medications (Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children, 2011; Panel on Treatment of HIV-Infected Pregnant Women and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission, 2010).

In general, to decrease the risk of transmission to an infant during labor, HIV-positive women who have a high viral load (HIV RNA copies exceeding 1000 copies/mL) near delivery should be considered for cesarean section at 38 weeks (Panel on Treatment of HIV-Infected Pregnant Women and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission, 2010). Discussion about treatment options and recommendations should not be threatening. The mother makes the final decision about the use of antiretroviral medications. Women who decide not to accept treatment with ZDV or other drugs should not face punitive action or denial of care (Panel on Treatment of HIV-Infected Pregnant Women and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission, 2010).

Because HIV-exposed infants, whether infected or uninfected, are more prone to acquiring opportunistic infections from an HIV-infected mother, prophylaxis of opportunistic infections is an important focus (CDC, 2009b). HIV-exposed infants are at particular risk from PCP, certain strains of tuberculosis, bacterial and viral infections, and fungal infections, such as Candida. The CDC (2009b) strongly recommends testing HIV-exposed infants for tuberculosis (TB) at 3 months of age, or if exposed to contagious TB. If positive, anti-TB medications are initiated. The CDC also recommends that varicella-zoster immune globulin be given to unimmunized infants within 96 hours of exposure to varicella or zoster infection.

Perhaps the most serious infection acquired by HIV-exposed infants is PCP. The CDC (2009b) strongly recommends that all HIV-exposed infants receive PCP prophylaxis with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole beginning at 4 to 6 weeks of age until the infant reaches 1 year. HIV-exposed infants for whom HIV infection has been ruled out may have PCP prophylaxis discontinued once HIV-negative status has been confirmed. After 1 year of age, infected children receive PCP prophylaxis according to CD4+ percentage or count, and prophylaxis may be discontinued with close monitoring if the child has been determined to have an acceptable percentage or count for 3 consecutive months (CDC, 2009b).

HIV-Infected Infants and Children

The Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children, available from www.aidsinfo.nih.gov, updates treatment recommendations regularly.

Treatment Considerations

Treatment is directed toward suppressing viral load with medications or combinations of medications that are in an acceptable and palatable form for children, that have the greatest effect while minimizing toxicity, that have an administration routine that maximizes the child’s and family’s quality of life, and that reduce the risk for medication resistance. Other goals of management for infants and children infected with HIV include facilitating optimal growth and development, providing ongoing support for the child and family, and referring the child for clinical trials as they become available (Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children, 2011). Infants and children who are HIV infected should be cared for by a multidisciplinary team of providers (physicians, nurses, social workers, pharmacists, dentists, nutritionists, psychologists, and outreach workers) led by specialists in pediatric HIV management (Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children, 2011).

More potent and improved antiretroviral medications have benefited HIV-infected children who have immunologic or clinical symptoms of HIV infection. These benefits include enhanced survival, improvements in growth and development, and reduced opportunistic infections and other complications related to HIV infection. Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has dramatically affected HIV-infected children’s health, although its rigorous treatment schedules are challenging for children and families to maintain. There are also associated short- and long-term toxicities, which can impact children (Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children, 2011).

Considerations of drug resistance and adherence are of primary importance. Before a medication routine is initiated, all infants and children with HIV should be tested for antiviral drug resistance. The rationale for this is that infants can acquire a drug-resistant strain of HIV from their HIV-infected mother or can develop drug resistance while receiving prophylaxis in anticipation of a diagnosis (Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children, 2011). Drug resistance testing should also be done when consideration is being given to changing a medication regimen. Resistance testing can help the specialist decide on antiviral drugs that are most appropriate for an individual child (Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children, 2011).

One of the most important factors to consider when deciding on a treatment approach is the child’s and the caregiver’s ability to adhere to the prescribed regimen, because failure to follow the regimen can result in the development of drug resistance and subsequent treatment failure. Adherence issues need to be addressed before a decision to start therapy is made, and adherence needs to be assessed and discussed at each visit (Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children, 2011). The Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children (2011) describes multimethod strategies for improving adherence, which include choosing a medication regimen that fits as much as possible into the child’s and family’s lifestyle, use of adherence aids (e.g., pillboxes, alarm watches, stickers), and providing ongoing teaching, support, and encouragement. A multidisciplinary team including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and sometimes peers is the most helpful to families. Strategies focus on both the child and the caregiver and must address any social issue that is affecting the family’s adherence to the prescribed regimen.

The Panel strongly recommends that the provider verify adherence by at least one means other than viral load monitoring at each visit. This can include strategies such as having the parent or child make available a medication log (self-report), doing pill counts or checking the refill history with a pharmacist, or using a modified form of directly observed treatment (m-DOT) (Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children, 2011). Adherence during adolescence can be even more challenging, so regimens may need to be reevaluated at that time.

Treatment Initiation

Currently, 20 antiretroviral agents have been approved for treatment of children with HIV infection; 15 of those are available in pediatric form (Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children, 2011). Drug classes include nucleoside analog reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs, NtRTIs), nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), protease inhibitors (PIs), entry inhibitors, and integrase inhibitors. The preferred drug combination for initial treatment of infants and children with HIV infection includes the following (Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children, 2011, p. 47):

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree