The Child with an Alteration in Tissue Integrity

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

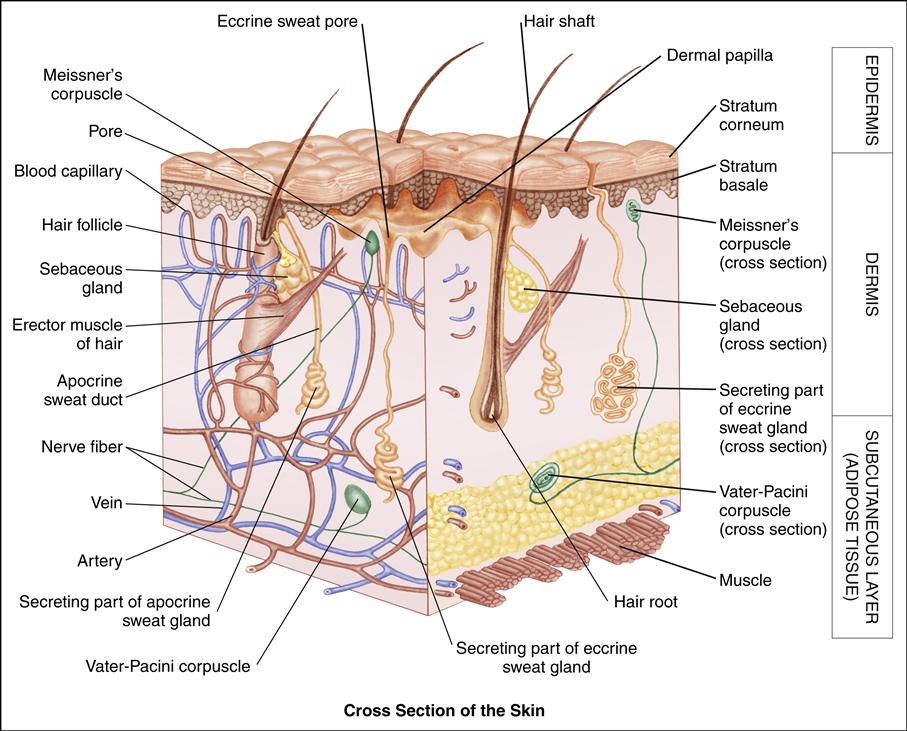

• Describe the anatomy and physiology of normal skin.

• Contrast characteristics of the neonate’s, child’s, and adult’s skin.

• Identify the manifestations of common skin disorders seen in infants and children.

• Discuss common causes of burns in children and the prevention of burn injuries.

• Analyze the implications of burn injuries in children.

• Discuss the classifications of depth, extent, and severity of a burn injury.

• Describe the therapeutic management and nursing care of children with minor burns.

• Apply the nursing process to the care of infants and children with skin disorders.

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/McKinney/mat-ch

Clinical Reference

Review of the Integumentary System

Knowledge of integumentary structure and function is necessary to understand the changes that occur with disease. There are a number of important differences between the skin of infants and young children and that of adults.

The skin has five major functions: (1) to protect the deeper tissues from injury, drying, and invasion by foreign matter; (2) to regulate temperature; (3) to aid in excretion of water; (4) to aid in production of vitamin D; and (5) to initiate the sensations of touch, pain, heat, and cold.

The skin is composed of two principal layers: the outer epidermis and the inner supportive dermis. Beneath these layers is the subcutaneous layer, which is composed largely of adipose tissue.

The epidermis is nonvascular stratified epithelium. It is divided into two major layers. The outermost layer, the stratum corneum, is a tough, horny collection of dead keratinized cells that have migrated up from the underlying layers. Keratin, a fibrous protein, is also the principal component of nails and hair. Skin cells are constantly being shed and replaced with new cells from the layers below.

The stratum basale, or basal cell layer, anchors the epidermis to the dermis. It contains dividing, undifferentiated cells that migrate upward toward the stratum corneum, differentiating into keratinocytes on their way. Epidermal replacement is relatively rapid; the epidermis is completely replaced about every 4 weeks. The stratum basale also contains melanocytes—the source of melanin, the pigment that gives skin its color.

The dermis, composed of tough connective tissue, contains lymphatics and nerves. The highly vascular dermis nourishes the epidermis.

Appendages from the epidermis—sebaceous glands, sweat glands, and hair follicles—are embedded in the dermis. The sebaceous glands arise from the hair follicles

and produce sebum, which lubricates the epidermis and is slightly bacteriostatic. Sebaceous glands are particularly abundant on the face and scalp. Hormones influence their activity, with testosterone increasing secretion and estrogen suppressing it.

There are two types of sweat glands. The eccrine sweat glands open directly onto the skin surface and produce sweat, which evaporates to reduce body temperature. Eccrine sweat glands are widely distributed over the body and are functionally mature by 2 months of age. The apocrine sweat glands produce a thick, milky secretion and open onto hair follicles. They are located mainly in the axillary and genital areas and become active during puberty.

Each hair is composed of a shaft and a root, which lie in a deep cavity of dermal cells called the hair follicle. There are several types of hair. Lanugo is the fine first hair that covers the body during fetal life and generally disappears before or shortly after birth. It is replaced by fine, nonpigmented vellus hair. Terminal hair covers all the ordinarily hairy parts of the body; it is coarse, long, and pigmented.

The subcutaneous layer, composed of fat cells, underlies the dermis. Adipose tissue helps cushion and insulate underlying structures.

The skin is a sensitive indicator of a child’s general health. Skin disorders are among the most common health problems in children. They may cause pain, pruritus, or changes in local sensation. Because the skin is visible and its disorders are often disfiguring, skin disorders can cause emotional and psychological stress for the child and family. Whether it is the discomfort and stress produced by an infant’s eczema or the emotional upset caused by an adolescent’s acne, these disorders can influence the child’s psychological and social development.

Nurses caring for children are in a unique position to assess the condition of children’s skin and to help children and families cope with skin disorders. Nurses can play an important role by teaching parents and children strategies to maintain healthy skin and prevent future skin problems.

Variations in the Skin of Newborn Infants

Parents typically inspect every inch of their newborn infant’s skin and continue to attend closely to variations in the skin of older infants. Regardless of whether the parent mentions it, the nurse may be sure the family is aware of spots, bumps, or rashes on the baby. Families frequently worry needlessly about skin lesions on infants, and the nurse can ease anxieties by pointing out and explaining the meaning and natural history of common skin variations.

Common Birthmarks

Most birthmarks are composed of cells of one or more of the skin’s normal elements. Any of the skin’s components can produce a birthmark, including melanocytes, blood vessels, epidermal cells, connective tissue, and hair follicles. The great majority of birthmarks are benign, although some can signal congenital syndromes, some can be associated with an increased risk for malignancy, and others can interfere with function or be disfiguring.

Etiology

Port-wine stains are the result of capillary malformation, whereas hemangiomas result from the proliferation of dilated capillaries and endothelial cells of the capillary linings. Salmon patches (nevus simplex) represent distended dermal capillaries and are believed to result from persistent fetal circulation. Mongolian spots are not vascular but the result of collections of pigment deep in the dermis. They occur as a result of arrested migration of melanocytes from the neural crest to the skin during embryonic development. Café-au-lait spots, light-brown pigmented areas, can appear anywhere on an infant’s body. Six or more of these lesions, if larger than 5 mm in diameter, suggest an underlying disorder, such as neurofibromatosis, Noonan syndrome, or McCune-Albright syndrome.

Incidence

Vascular birthmarks are extremely common, with most references estimating an incidence of occurrence in at least 20% to 40% of neonates. Port-wine stains occur in 3 in 1000 live births (Vascular Birthmarks Foundation, 2010), and about 1% to 2% of all newborn infants have hemangiomas (Morelli, 2011). The most common vascular lesion is the salmon patch, which some references estimate to occur in as many as 40% of neonates. The incidence of mongolian spots is proportional to the depth of the baby’s pigmentation. As many as 80% of African-American, Asian, and American Indian infants are born with mongolian spots. Fewer than 10% of white infants have mongolian spots (Morelli, 2011).

Manifestations

The port-wine stain is present at birth. At first it is only faintly colored and flat, but it becomes darker as the child grows. In some cases, underlying bone and tissue may enlarge as well. The port-wine stain is permanent, and by middle age, the mark may be dark purple and rough or nodular. Hemangiomas, conversely, are not usually visible at birth but appear during the first few weeks of life and then grow during the first year. Generally, they begin to disappear spontaneously after 1 year of age and are gone by age 5 or 6 years of age. The salmon patch is a flat, pink, irregular-shaped spot on the nape of the neck; on the forehead; between the eyes; on the eyelids; or around the nasolabial folds. Commonly called “stork bites” or “angel kisses,” these lesions are benign and usually fade during the first year of life. Salmon patches typically appear darker when the child is crying. Mongolian spots are present at birth and appear as flat, gray-green or blue lesions similar to bruises. They are most commonly distributed on the lumbosacral regions or buttocks, although they can appear on any part of the body. Mongolian spots generally fade completely by the time the child is 4 to 5 years old.

Diagnostic Evaluation

The appearance of most birthmarks is sufficient to make a diagnosis, although biopsy and histologic evaluation are definitive. Rarely, some hemangiomas are signs of more serious underlying disorders. Worrisome hemangiomas include those with large, segmented facial distributions, those with a beard distribution, and those that involve the gluteal cleft. Magnetic resonance imaging is typically performed to rule out underlying anomalies (Chan, Haggstrom, Drolet, et al., 2008).

Therapeutic Management

Other than education, treatment for salmon patches and mongolian spots is not indicated. Treatment for port-wine stains is not indicated in the neonatal period, but their identification should prompt evaluation for associated congenital syndromes, such as Sturge-Weber, Beckwith-Wiedemann, and Klippel-Trénaunay syndromes. Conservative management of port-wine stains in older children includes instructions in concealing the lesions with makeup and psychotherapy if needed. Pulsed dye laser therapy is the treatment of choice for darker port wine stains (Morelli, 2011).

The treatment for hemangiomas includes simple observation as the lesion involutes on its own, pharmacotherapy, surgical excision, radiation, and laser therapy. Active intervention is reserved for hemangiomas that interfere with function, such as those that obstruct the nose, mouth, or eyes or lesions that tend to ulcerate and bleed frequently. Pharmacologic approaches include injection of steroids into the lesion, oral steroids, and topical imiquimod. The argon laser tends to relieve the symptoms of ulcerated hemangiomas in a matter of days, and involution typically follows. A rapidly growing, deep hemangioma may be a sign of Kasabach-Merritt syndrome, a syndrome in which the child experiences a coagulation disorder that results in thrombocytopenia, severe anemia, and collecting of platelets within the hemangioma. This may be life threatening (Morelli, 2011).

Nursing Considerations

Assess the child’s entire body for distribution, size, and shape of lesions. Assess hemangiomas for symptoms such as ulceration or bleeding and for potential to obstruct function. Assess the extent of the parents’ knowledge regarding the infant’s birthmarks.

Parents are frequently anxious about newborn infants’ skin lesions, and it is not unusual to discover that parents already have acquired misinformation from friends and family members about the meaning and prognosis of birthmarks. Common anxiety-provoking beliefs include the ideas that prominent lesions are malignant or that the mother caused the lesions by careless behaviors during her pregnancy.

The parents should receive a simple, scientific explanation for the skin lesions and instructions regarding the usual skin care for neonates (see Parents Want to Know: Care of Newborn and Infant Skin). Parents should be made aware of the expected course of their child’s lesion, and their expectations should be explored. Nurses can reassure parents when the lesions are benign and educate them thoroughly about what to expect when treatment is indicated.

Skin Inflammation

Inflammatory conditions that affect the child’s skin can be acute or chronic. A primary nursing goal when caring for a child with an inflammatory skin condition is to prevent secondary infection.

Seborrheic Dermatitis

Seborrheic dermatitis is a chronic inflammatory skin condition seen frequently in infants. It is referred to as “cradle cap” when located on the scalp. It often begins in the first 2 to 3 weeks of life and usually disappears by age 12 months. Seborrhea in older children might appear on the face, behind the ears, around the umbilicus, or in any other area with a large number of sebaceous glands. Although the precise cause is unknown, seborrhea appears to be related to sebaceous gland dysfunction and overgrowth of the fungi Candida and Malassezia ovalis (Poindexter, Burkhart, & Morrell, 2009).

Seborrheic dermatitis is characterized by nonpruritic, oily, yellow scales that block sweat and sebaceous glands, causing retained secretions and inflammation in affected areas (Figure 49-1). Confluent erythema might be present in the diaper and intertriginous areas and around the umbilicus (Figure 49-2). Often, there is overgrowth of normal skin bacteria and yeast, which increases inflammation and leads to secondary infection.

The nurse inspects the infant’s scalp or other affected areas for lesions and inflammation and questions parents about the frequency and technique of washing the infant’s scalp. Instruct the parents to remove the scales daily by shampooing with a mild baby shampoo or an over-the-counter antiseborrheic shampoo containing sulfur and salicylic acid (Fostex Medicated Cleansing, P&S liquid, Sebulex), selenium, or tar (Neutrogena T/Gel, Polytar). Ketoconazole 2% shampoo has been reported to be safe in infants less than 12 months of age (Poindexter et al., 2009). Massaging the scalp with warm mineral oil before shampooing helps loosen scales. Using a fine-tooth comb or a clean, soft-bristle toothbrush during the shampoo also helps loosen scales. Eyelid dermatitis (blepharitis) is treated with warm tap water compresses and cleansing with “no tears” baby shampoo. Care must be taken to keep topical medications out of the infant’s eyes.

Teach the parents the importance of good hygiene of the infant’s scalp and skin to prevent recurrence. Reassure them that the fontanel is not fragile and will not be damaged by gentle pressure and washing. Advise the parents to contact the physician if the sites become infected. Skin lesions that do not clear with frequent washing can be treated with hydrocortisone cream applied twice a day.

Seborrheic dermatitis of the diaper area is often secondarily infected with Candida albicans and requires appropriate treatment. Lotions and creams tend to aggravate the condition and should not be used.

Contact Dermatitis

Contact dermatitis is a skin inflammation that results from direct skin-to-irritant contact.

Etiology

Contact dermatitis can be caused by hundreds of substances. Among the most common causes of contact dermatitis are rubber products, clothing dyes, nickel (in jewelry, bra strap hooks, jeans fasteners), and plant oils. Scented or strongly alkaline soaps, skin lotions, cosmetics, and wool clothing also are irritating to many children.

Diaper dermatitis (diaper rash) is a contact dermatitis from irritants such as moisture, friction, and chemical substances. Urine ammonia, formed from the breakdown of urea by fecal bacteria, is extremely irritating to sensitive infant skin. Ammonia alone does not cause skin breakdown. Only skin damaged by infrequent diaper changes and constant urine and feces contact is prone to damage from ammonia in urine. Inadequate fluid intake, heat, and detergents in diapers aggravate the condition.

Incidence

Irritant contact dermatitis is more common in children than is allergic contact dermatitis. Many children have at least one episode of diaper dermatitis, usually occurring between ages 3 and 18 months, although it is most common between ages 8 and 10 months (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP], 2010).

Manifestations

Manifestations of irritant contact dermatitis include dry, inflamed, and pruritic skin. The distribution of lesions correlates with the skin surface in contact with the offending agent (e.g., watchband, clothing). Diaper dermatitis begins with erythema in the perianal region and can progress to macules and papules, which form erosions and crusts (Figure 49-3). Manifestations of allergic contact dermatitis include blistering; weeping lesions over an area of inflamed skin; intense pruritus; and crusted, scaly lesions that heal in 10 to 14 days without treatment. Rhus dermatitis (e.g., poison ivy, oak, sumac) may cause severe systemic reactions.

Diagnostic Evaluation

The characteristic appearance of the lesions and a history of exposure to an irritating substance establish the diagnosis. Skin testing might be performed in children with persistent or recurrent dermatitis.

Therapeutic Management

Discontinuing exposure to the offending agent treats contact dermatitis. The skin should be washed thoroughly if any irritant remains on the skin. Cool compresses of tap water or Burow’s solution or steroid cream (e.g., triamcinolone 0.1% or fluocinolone 0.025%) may be applied several times a day after application of compresses. Severe contact dermatitis might require treatment with oral steroids, which should be tapered gradually. Desensitization therapy is usually not effective in managing contact dermatitis.

Nursing Care

The Child with Contact Dermatitis

Assessment

Investigate new or continuing exposure to any potentially irritating substances. Assessment of skin lesions includes noting their distribution and configuration and looking for evidence of pruritus.

For a child with diaper dermatitis, carefully inspect the diaper area, noting the type and extent of lesions. It is important to assess the infant’s hygiene and the parents’ knowledge of care related to the infant’s skin integrity. Question parents about the type of diapers used, laundering practices, and frequency and method of cleaning the diaper area. Any recent changes in the infant’s care, such as new foods, soaps, detergents, or lotions, should be investigated.

Nursing Diagnosis and Planning

The nursing diagnoses and expected outcomes that may be appropriate for the child with contact dermatitis and the child’s family are as follows:

Expected Outcomes

The child will have reduced skin irritation, as evidenced by decreased excoriation and increased healing. The child will exhibit decreased irritability, absence of scratching, and uninterrupted periods of sleep.

Expected Outcome

The child will have no signs of secondary bacterial infection, as evidenced by clear intact skin.

Expected Outcomes

The child and family will identify and avoid irritating substances and will carry out prescribed treatments correctly.

Interventions

Nursing care of the child with contact dermatitis is directed toward relieving itching, preventing infection, and identifying and removing offending substances. Cool compresses and tepid oatmeal (Aveeno) baths provide some relief from itching. Prescribed topical steroid creams should be applied in a thin layer. Antihistamines, such as diphenhydramine (Benadryl) or hydroxyzine (Atarax), also help the child rest. Because overheating increases itching, advise the parents to occupy the child with quiet activities and to keep the room temperature at a comfortable level.

Reassure the parents and child that the lesions are not contagious and cannot be spread to others or to other parts of the body by scratching. However, if oils from rhus plants remain on the skin, nails or on clothing, they may contact other parts of the child’s body and cause new lesions at the point of contact. Keep the skin clean and help the child avoid scratching to prevent secondary infection. Instruct the parents to contact the health provider if the child has a fever or if the lesions produce purulent drainage.

Contact dermatitis is prevented by avoiding offending substances. Children should be taught to recognize plants of the rhus group. If the child is exposed to these plants, rinse the skin with cool water immediately (within 15 minutes) and wash clothing in hot, soapy water. Oleoresins in the plants can be spread not only by direct contact with the plant but also in the smoke of burning leaves or by touching pets that have contacted the plants.

Avoiding known irritants, such as cosmetics, jewelry, and canvas athletic shoes, can prevent other types of contact dermatitis. Nickel-sensitive children can usually tolerate 14-karat gold or sterling silver jewelry. Pierced earrings should have hypoallergenic or surgical stainless steel posts.

Diaper dermatitis is much easier to prevent than to treat. Successful treatment and prevention of diaper rash, regardless of the cause, depend on cleaning the diaper area thoroughly and keeping the skin dry. Prompt, gentle cleaning with water and mild soap (Dove, Neutrogena Baby Soap) after each voiding or defecation rids the skin of ammonia and other irritants and decreases the chance of skin breakdown and infection. Careful attention should be given to skin folds and creases. The parent should pat the skin dry with a soft cloth towel after washing. Air drying the skin and frequently exposing the skin to air and light promote healing of diaper rash. During bouts of diaper rash, the diaper may be left off during nap times.

A bland, protective ointment (A & D, Balmex, Desitin, zinc oxide) can be applied to clean, dry, intact skin to help prevent diaper rash. Ointments should not be applied to inflamed areas because they retain moisture. Occlusion increases the risk of systemic absorption of steroid; thus steroid creams are rarely used for diaper dermatitis because the diaper functions as an occlusive dressing. Frequent diaper changes decrease irritation from urine and feces. Encourage the parent to check the newborn infant’s diaper every hour and the older infant’s diaper every 2 hours. Using disposable diapers does not eliminate the need for frequent diaper changes. Although the “wicking” action of disposable diapers pulls moisture away from the skin toward the liner, ammonia and other byproducts are left behind on the infant’s skin, causing irritation. Rubber or plastic pants increase skin breakdown by holding in moisture and should be used infrequently.

If cloth diapers are laundered at home, the parent should wash them in hot water, using a mild soap and double rinsing. Soaking diapers before washing in a quaternary ammonium compound (Diaparene) decreases ammonia in the diapers. Using ¼ cup of vinegar in the rinse is also helpful.

Advise the parent to contact the health provider if the rash becomes solid and bright red, if it becomes raw or bleeds, if blisters or boils develop, if the rash does not improve in 3 days with treatment, or if the infant has a fever.

Evaluation

Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis, or eczema, is a common chronic inflammatory disease of the skin characterized by severe pruritus. Atopic dermatitis can have distressing psychosocial effects on the child and family.

Etiology

The cause of atopic dermatitis (eczema) is unknown, but the disease is thought to be genetically determined and related to a malfunction in the body’s immune system. Contributing factors include an inherited tendency for dry, sensitive skin; allergy; and emotional stress. Most children with atopic dermatitis have a family history of asthma, hay fever, or atopic dermatitis. Children with atopic dermatitis may present with asthma or allergic rhinitis. Although the role of allergy in the etiology of atopic dermatitis is controversial, immunoglobulin E (IgE)–mediated food allergy has been shown to be an exacerbating factor in some children (Leung, 2011).

Incidence

The prevalence of atopic diseases, including asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis, has increased substantially in the past 30 years. Atopic dermatitis usually begins in infancy and clears by age 2 or 3 years, although it can persist through adolescence and adulthood. Data suggest that high birth weight and daycare attendance increase the risk for atopic dermatitis in infancy, whereas exclusive breastfeeding decreases the risk (Bartick & Reinhold, 2010; Scholtens, Gehring, Brunekreef, et al., 2007). Atopic dermatitis affects all races. Symptoms tend to be worse during winter months.

Manifestations

During infancy, erythematous areas of oozing and crusting appear first on the cheeks and then on the forehead, scalp, and extensor surfaces of the arms and legs (Figure 49-4). Papulovesicular rash and scaly, red plaques become excoriated and

lichenified. The affected scalp area resembles seborrheic dermatitis, but unlike seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis is intensely pruritic. Infants begin manifesting symptoms at approximately age 1 to 4 months.

Children who have atopic dermatitis after infancy have a rash pattern that differs from the rash seen during infancy. The flexor surfaces of the wrists, ankles, knees, and elbows are affected, as are the neck creases, the eyelids, and the dorsal surfaces of the hands and feet. There may be acute weeping areas, with or without secondary infection. Chronic lichenification results from persistent scratching.

Children and adolescents with atopic dermatitis readily experience intense itching, especially in response to sweating or contact with irritating fabrics, such as wool. Emotional upset increases sweating and precipitates itching and scratching. Dry skin is a hallmark of this condition.

Diagnostic Evaluation

The diagnosis is based on the clinical features of intense pruritus, the appearance of the lesions, the pattern of remissions and exacerbations, and a family history of allergy. IgE levels and eosinophils are often elevated. Skin testing for food allergies—usually milk, eggs, wheat, soy, peanuts, and fish—can help identify potential food triggers.

Therapeutic Management

The main goals of treatment are to control itching and scratching, moisturize the skin, prevent secondary infection, and remove irritants and allergens. Control of pruritus includes avoiding environmental triggers, such as overheating, soaps, wool clothing, and other skin irritants. Oral antihistamines, such as hydroxyzine (Atarax), diphenhydramine (Benadryl), and loratadine (Claritin), can be used to help break the “itch-scratch-itch” cycle. Nonsedating antihistamines, such as loratadine, may be preferred for school-age children. Itching is typically more severe at night; thus antihistamines should be given before bedtime. Secondary infection is treated with antibiotic therapy.

Proper skin hydration is essential. Either a “dry” or “wet” approach may be used. The dry approach depends on avoiding bathing and the liberal use of emollients on dry skin. The wet approach is currently more popular. It permits bathing for limited periods of time, and the use of wet compresses and occlusive creams and ointments are the mainstays of treatment. In humid climates, bathing should be infrequent, and only lukewarm water and mild, nonperfumed soap (e.g., Purpose, white Dove, Basis) should be used. Emollients such as Eucerin cream or petroleum jelly applied immediately after bathing to damp skin help the skin retain moisture. Applying the moisturizer while the skin is still damp hydrates the skin. The child who lives in a dry climate should bathe frequently (several times a day), using a hydrophilic agent such as Cetaphil instead of soap, and should moisturize with a moisturizing ointment or cream immediately after bathing. The child should avoid lotions that contain alcohol because these can contribute to skin dryness. Regardless of the approach used, moisturizing the skin is maintenance therapy for atopic dermatitis and should become a daily routine for the child.

Antiinflammatory corticosteroid creams and ointments are prescribed for inflamed or lichenified areas. These creams are more effective when applied to damp skin. The lowest potency that controls signs should be used, and topical steroids are usually reserved for treatment of episodic flares.

Topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs), such as tacrolimus and pimecrolimus, have an antiinflammatory action and can be used in place of topical corticosteroids in children older than 2 years of age who do not respond well to other treatment approaches (Leung, 2011). Patients should avoid exposure to sunlight, tanning beds, sun lamps and any other sources of ultraviolet light while taking these medications.

These drugs are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for children older than 2 years of age. They may be applied to 100% of the body surface if needed, and they may be used for longer periods of time than topical steroids may. Topical immunomodulators do not cause skin atrophy. Although they can penetrate the skin enough to suppress local inflammation, they are only minimally absorbed into the circulation.

Routine blood studies (to monitor for immunosuppression) in children using tacrolimus and pimecrolimus are not indicated. However, caution should be used in children whose skin integrity had widespread damage because immunosuppressives can be absorbed systemically in such cases.

TCIs have become popular for use in children with atopic dermatitis; however, postmarketing surveillance reveals risks. An FDA advisory panel recommended adding a black box warning to labels informing consumers that calcineurin inhibitors are associated with increased risk for certain cancers, especially in children (American Academy of Dermatology, 2010).

Identifying and eliminating allergens can be helpful. Allergy-proofing the home might be recommended (see Chapter 42). Because allergy to certain foods is an exacerbating factor in some children, those foods should be eliminated from the diets of sensitive infants. Breastfeeding for the first year is recommended for infants at risk for allergy. Solid foods should not be introduced until the infant is at least 6 months old.

Nursing Care

The Child with Atopic Dermatitis

Assessment

Obtain a thorough history that includes information about allergies in the family. Question parents about any environmental or dietary factors that seem to worsen the child’s condition. Determine what treatments have been tried and their effectiveness. Examine skin lesions for type, distribution, and evidence of any secondary infection. Assess the child’s comfort level and the family’s feelings and coping methods.

Nursing Diagnosis and Planning

The nursing diagnoses and expected outcomes that may be appropriate for the child with atopic dermatitis and the child’s family are as follows:

Expected Outcome

The child’s skin will exhibit decreased evidence of dryness, irritation, and excoriation.

Expected Outcomes

The child will have minimal pain and pruritus, as evidenced by decreased irritability, absence of scratching, and uninterrupted periods of sleep.

Expected Outcome

The child will have no signs of secondary bacterial infection, as evidenced by a normal body temperature and absence of purulent drainage.

Expected Outcomes

The child and family will identify and eliminate allergens and aggravating factors. The family will carry out prescribed treatments correctly. Family members will express any anxiety related to the child’s condition.

Expected Outcome

The child and family will discuss their feelings and concerns.

Expected Outcomes

The child will engage in activities with other children. The child will verbalize positive ideas about self.

Interventions

Care of the child with atopic dermatitis is demanding, and the entire family routine may revolve around the affected child. Parents need support and reassurance as they care for an uncomfortable, often irritable child.

Keeping the child’s skin hydrated will help relieve itching. Instruct parents to apply a moisturizing cream, such as Eucerin, several times a day and immediately after the child is bathed. Reassure parents that moisturizing creams contain no harmful drugs and should be applied whenever the child’s skin looks dry. Soaks and cool, wet compresses are soothing and can be applied to remove crusts, reduce inflammation, and dry weeping areas. Provide parents with explicit instructions on the use of soaks and topical medications. Strips of old cotton sheets moistened in lukewarm or cool tap water work well for wet dressings. Wet compresses should not be used for more than 3 days.

Rough clothing can aggravate eczema, particularly wool or other fabrics that cause sweating. Soft cotton or cotton-polyester blends are tolerated best. Undergarments with irritating seams can be turned inside out so that the soft seam is against the skin. Heat and sweating increase pruritus, so instruct parents to be careful not to “bundle up” the child in heavy blankets or clothing. Because detergents and fabric softeners can also aggravate atopic dermatitis, clothes should be washed in mild detergent and rinsed twice.

Advise the parents to keep the child’s fingernails clean and short. Cotton gloves or mittens might be needed to prevent excoriation from scratching but should be used with caution, preferably only at night, because overuse could interfere with fine motor development. Lightweight, long-sleeved tops and one-piece outfits discourage scratching.

The child’s skin must be kept clean to minimize secondary infection. Avoid using soap. Bath oil or emulsifying ointment can be used as a soap substitute but must be used with caution because these cause both the child and the tub to become slippery. Tepid bath water helps prevent the child from becoming overheated and itchy. Instruct parents to contact the physician at the earliest signs of skin infection (weeping skin, pustules) and to administer topical and oral antibiotics as prescribed.

Children with atopic dermatitis who swim should apply moisturizer before swimming and immediately on exiting the pool. Prolonged immersion in water (more than 20 minutes) can have a drying effect. A humidifier in the child’s room during winter months may decrease skin dryness. The child should avoid the drying effects of sun exposure.

Children and families of children with atopic dermatitis exhibit frustration when the condition does not resolve quickly. The parent or child might be concerned about the child’s appearance, as well as the child’s discomfort.

Although studies do not consistently support emotional upset as a direct cause of atopic dermatitis flares, it is helpful to teach an older child stress reduction techniques to help cope with the frustration and discomfort of the condition. A resource for families of a child with atopic dermatitis is the National Eczema Association for Science and Education.

Evaluation

• Is the child’s skin intact and smooth?

• Have itching and pain been reduced?

• Is the child’s skin free from redness or purulence that would indicate secondary infection?

• Do parents carry out prescribed treatments correctly?

• Are parents able to demonstrate appropriate coping techniques?

• Can the child demonstrate stress relief measures to decrease itching?

Skin Infections

Skin infections are common in childhood. Bacteria are normally present on healthy skin. The skin’s susceptibility to bacterial infection depends on several factors, including the intactness of the skin, the virulence of the organisms, and the child’s immune status. Children are susceptible to fungal and viral infections, as well. Unlike bacterial infections, which generally respond fairly quickly to treatment, fungal and viral infections can be more persistent and challenging to treat.

Although bacterial skin infections can be caused by a variety of microbes, Staphylococcus is a major pathogen, accounting for most of the skin infections of childhood. Skin infections predominantly caused by Staphylococcus aureus can range from minor, superficial lesions to severe generalized lesions with systemic effects. These skin infections include folliculitis, furuncles (boils), cellulitis, bullous impetigo, nonbullous impetigo, and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Impetigo, a superficial, usually minor staphylococcal infection, is the most common bacterial skin infection of childhood. Folliculitis is inflammation of hair follicles. Furuncles, or boils, develop when the infection of an existing folliculitis progresses deeper. Cellulitis is infection of the subcutaneous tissues.

Impetigo

Impetigo often occurs as a secondary infection from another skin lesion, such as an insect bite. Close contact contributes to the spread of impetigo, which is highly contagious. Children in daycare facilities, schools, or camps and adolescent athletes are at increased risk. The incubation period for impetigo is 7 to 10 days, and it may spread to other parts of the child’s skin or to others who touch the child, use the same towel, or drink from the same glass. Spread of the infection is fostered by poor hygiene; crowded living conditions; and a hot, humid environment. Lesions resolve in 12 to 14 days with treatment.

Etiology

Impetigo can be caused by S. aureus, group A beta-hemolytic streptococci, or a combination of these bacteria. S. aureus is the primary pathogen in most cases. Nonbullous impetigo, sometimes referred to as crusted impetigo, was formerly thought to be a result of streptococcal infection. Studies have shown that S. aureus is the primary cause of both bullous and nonbullous impetigo (Schor, 2010). Bullous impetigo is at the minor end of a spectrum of blistering disorders caused by the exfoliative toxins produced by some strains of Staphylococcus. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is at the more severe end of that spectrum.

Incidence

Impetigo occurs most often during hot, humid summer months. Toddlers and preschoolers are most commonly affected, often when recovering from an upper respiratory tract infection.

Manifestations

The primary lesions of impetigo occur in two forms. Bullous impetigo characteristically manifests as small vesicles that can progress to bullae. The lesions are initially filled with serous fluid and later become pustular. The bullae rapidly rupture, leaving a shiny, lacquered-appearing lesion surrounded by a scaly rim. Crusted impetigo appears initially as a vesicle or pustule that ruptures to become erosion with an overlay of honey-colored crust. The erosions bleed easily when crusts are removed (Figure 49-5). Lesions are mildly pruritic. Scarring is uncommon but may occur if the child picks or scratches the lesions. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is a frequent sequel in dark-skinned children. The lesions are often located around the mouth and nose but can appear on any part of the body.

Diagnostic Evaluation

The characteristic appearance of the lesions usually confirms the diagnosis. Failure to respond to treatment may suggest community-acquired methicillin-resistant S. aureus (CA-MRSA) (see Chapter 41), an increasing problem in children (Bar-Meir & Tan, 2010). If a culture is ordered, the specimen should be obtained from beneath the crust or from the fluid inside the lesions.

Therapeutic Management

Impetigo is treated with topical and oral antibiotics. The lesions should be gently washed three times a day with a warm, soapy washcloth and the crusts soaked and carefully removed. A topical ointment, such as mupirocin (Bactroban) or bacitracin (Baciguent), is then applied to the lesions. Topical therapy lasts 7 to 10 days. Severe cases of impetigo or cases of impetigo around the mouth are treated with oral antibiotics that are effective against both staphylococcal and streptococcal organisms. Impetigo that is extensive is treated with intravenous (IV) antibiotics. Antibiotic treatment of streptococcal impetigo does not prevent glomerulonephritis, but it does hasten healing of the lesions.

Good handwashing and careful hygiene are imperative to prevent spread of the infection and should be emphasized to the child and parents. The child should not attend school or daycare for 24 hours after beginning treatment (AAP, 2009). The school should be notified of the diagnosis.

Nursing Care

The Child with Impetigo

Assessment

Assess the child’s skin for the size, distribution, and spread of impetigo lesions. If the child is taking systemic antibiotics, monitor for signs of adverse effects, such as rashes or diarrhea. Observe for periorbital edema or blood in the urine, which may signal the development of acute glomerulonephritis if the impetigo is caused by group A, beta-hemolytic streptococci.

Nursing Diagnosis and Planning

The nursing diagnoses and expected outcomes that may be appropriate for the child with impetigo and the child’s family are as follows:

Expected Outcomes

The child will maintain skin integrity, as evidenced by confinement of the infection to the primary site. The area will heal without scarring or further infection.

Expected Outcomes

The child and family will adhere to measures to prevent the spread of infection. The parent will demonstrate care of the lesions and administration of medications.

Interventions

Teach parents to soak the crusts and then wash them off with a warm, soapy washcloth three times a day. Advise them to gently remove the crusts after soaking, taking care not to spread the infection to other parts of the body with the contaminated washcloth. Antibiotic ointment should then be applied to the lesions and the affected areas left open to air. A small amount of bleeding after crust removal is common.

The child should sleep alone and should be bathed daily, alone, with antibacterial soap. The caregiver should wear gloves when caring for the child. Emphasize the importance of administering the full course of topical or systemic antibiotics as prescribed.

Evaluation

• Are the lesions healing, and have they remained confined to the primary site?

• Do the parents appropriately explain the necessity for administering the full course of treatment?

Cellulitis

Cellulitis is bacterial infection of the subcutaneous tissue and the dermis. It is usually associated with a break in the skin, although cellulitis of the head and neck can follow an upper respiratory tract infection, sinusitis, otitis media, or tooth abscess. Cellulitis occurs most commonly in the lower extremities and in the buccal (inside the cheek) and periorbital (around the eye) regions. Complications of cellulitis include septic arthritis, meningitis, and brain abscess. Periorbital cellulitis can lead to blindness.

Etiology and Incidence

Since the introduction of the Haemophilus influenzae type B vaccine, group A streptococci and S. aureus are the most common causes of cellulitis. Cellulitis is most common in children age 2 years and younger.

Pathophysiology

Bacteria overwhelm the defensive cells that normally contain inflammation to local areas. The result is more extensive invasion of the causative organism as the infection moves from superficial tissue to deeper subcutaneous tissue.

Manifestations

The affected area is red, hot, tender, and indurated. If H. influenzae is the suspected organism, the affected area might have a purplish tinge. Edema and purple discoloration of the eyelids and decreased eye movement are present in periorbital cellulitis. Lymphangitis may be seen, with red “streaking” of the surrounding area and enlarged regional lymph nodes (lymphadenitis). The child usually exhibits fever, malaise, and headache.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Usually a complete blood cell count, blood cultures, and culture of the affected area are done. If no drainage is present, the affected area can be aspirated. Orbital cellulitis can be diagnosed by computed tomography of the orbit.

Therapeutic Management

After an initial intramuscular or IV dose of an antibiotic, such as ceftriaxone, the child with cellulitis of an extremity is usually treated at home with a 10-day course of oral antibiotics (cephalosporin, cloxacillin, or dicloxacillin) and warm compresses. If the cellulitis involves a joint or the face, or if the child shows other signs of acute febrile illness, hospitalization and IV antibiotics are required. Incision and drainage of the affected area may be necessary. Community acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA) is increasingly becoming a problem in children and adolescents, particularly athletes (Hinckley & Allen, 2008). Lesions, especially abscesses, should be cultured for presence of methicillin-resistant staphylococcal organisms because treatment of CA-MRSA is tailored to sensitivity results. Effective antibiotics for CA-MRSA infection in children include sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, clindamycin, vancomycin, and linezolid (see Chapter 41).

Nursing Care

The Child with Cellulitis

Assessment

Record the history and question the parent regarding recent ear infections, dental caries, or trauma to the skin surrounding the affected area. Other pertinent data include when the inflammation started and how rapidly it has progressed. Examine the skin, noting any temperature increase, swelling, redness, and drainage. Assess for fever, pain, guarding, and irritability.

Nursing Diagnosis and Planning

The nursing diagnoses and expected outcomes that may be appropriate for the child with cellulitis and the child’s family are as follows:

Expected Outcome

The child will exhibit signs of healing, such as decreases in redness, swelling, and fever.

Expected Outcome

The child will be able to sleep and will demonstrate decreased irritability.

Expected Outcome

The family will describe measures to prevent the spread of infection, will describe how to administer antibiotics as prescribed, and will demonstrate the ability to carry out treatment measures.

Interventions

The child should rest in bed with the affected extremity elevated and immobilized. Warm, moist soaks applied every 4 hours increase circulation to the infected area, relieve pain, and promote healing. Acetaminophen can be given to control fever and pain. Frequent hand hygiene is essential to prevent the spread of infection. If the child is hospitalized, IV antibiotics should be administered accurately and on time to maintain a therapeutic blood level. If the child is being treated at home, the parents must understand the importance of administering the entire course of antibiotics as ordered. The child should be carefully monitored for signs of sepsis (increased fever, chills, confusion) and spread of infection.

Evaluation

Candidiasis

Thrush (oral candidiasis) (Figure 49-6) is a superficial fungal infection of the oral mucous membranes that is common in infants. Thrush occurs as a result of overgrowth of C. albicans. In addition to oral lesions, the child may exhibit lesions in the diaper area, which are caused by C. albicans passing through the intestine. Moisture and heat in the diaper area create an environment favorable to the development of Candida dermatitis. Persistent candidiasis suggests that the child might be immunocompromised.

Etiology

A neonate can acquire candidiasis during delivery while passing through an infected vagina. An older infant may have a fungal overgrowth as a result of immunosuppression, during antibiotic therapy, from exposure to the mother’s infected breasts, or from unclean bottles and pacifiers.

Incidence

Candidiasis occurs most often in infants. Predisposing factors in all age-groups include antibiotic therapy, diabetes, and altered immune status.

Manifestations

White, curdlike plaques are noted on the tongue, gums, and buccal mucosa in children with thrush. They can be distinguished from milk curds by the difficulty encountered in removing them and the bleeding of an erythematous base when plaques are removed. A child with severe infection may have difficulty eating. The lesions of Candida diaper dermatitis are usually bright red and coalesced, with some satellite lesions spreading out to the child’s abdomen and thighs (Figure 49-7).

Diagnostic Evaluation

The diagnosis of thrush and candidal diaper dermatitis is made from the clinical appearance of the lesions.

Therapeutic Management

Nystatin oral suspension (100,000 units/mL), swabbed onto the mucous membranes of the mouth, is effective in treating thrush. Because Candida is present in the gastrointestinal tract, oral nystatin also may be ordered to decrease the likelihood of recurrence. Oral fluconazole is an alternative therapy. Candidal diaper dermatitis is treated with a topical antifungal agent, such as nystatin or clotrimazole (Lotrimin).

Nursing Care

The Child with Candidiasis

Assessment

Nursing assessment includes obtaining a history of maternal and infant Candida infections. Question the mother regarding vaginal itching or discharge or any nipple tenderness or redness. Also discuss methods used to clean bottles and pacifiers. Examine the infant’s mouth and diaper area and assess nutrition and hydration status.

Nursing Diagnosis and Planning

The nursing diagnoses and expected outcomes that may be appropriate for the child with candidiasis and the child’s family are as follows:

Expected Outcome

The infant will exhibit signs of healing lesions, as evidenced by pink, intact mucous membranes or resolution of diaper rash.

Expected Outcome

The infant will have reduced discomfort, as evidenced by ability to take feedings without difficulty, decreased fussiness, and improved ability to sleep.

Expected Outcomes

The family will demonstrate methods to prevent spread of infection and will administer the entire course of medication as prescribed.

Expected Outcomes

The infant will accept feedings and will consume appropriate amounts of nutrients.

Interventions

Teach the parent to swab 1 mL of oral nystatin suspension onto the infant’s gums, tongue, and buccal mucosa every 6 hours until 3 to 4 days after symptoms have disappeared. Because cotton-tipped applicators tend to absorb the medication, a more effective method of administration is to rub the suspension onto the mucous membranes with a gloved finger. To increase the amount of time the medication is in contact with the mucous membranes, nystatin should be applied after feedings. Alternatively, oral fluconazole administered once a day may be used for treatment of thrush in infants.

Pacifiers, nipples, and bottles should be thoroughly cleaned to decrease the chance of reinfection. Teach the parents the technique and importance of good hand hygiene. If the infant is breastfed, the mother’s breasts should also be treated with nystatin.

Suggest small, frequent feedings for the infant or child with thrush who is uncomfortable. Cool liquids are soothing to the older child.

For the infant with candidal diaper dermatitis, suggest that the parent apply nystatin or clotrimazole cream. Leaving the diaper area exposed to air reduces the moisture that facilitates fungal growth.

Advise the parent to contact the health care provider if the infant refuses to eat or fever develops or if the candidiasis does not clear with treatment.

Evaluation

Tinea Infection

Tinea is a superficial skin infection caused by a group of fungi known as dermatophytes. Tinea infections are designated by the word tinea followed by the Latin word for the affected part of the body. Figure 49-8 illustrates various types of tinea infections.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree