Health Promotion for the Adolescent

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

• Describe the adolescent’s normal growth and development.

• Identify the sexual maturity rating and Tanner stages and recognize deviations from normal.

• Describe the developmental tasks of adolescence.

• Describe the concept of identity formation in relation to adolescent psychosocial development.

• Describe appropriate health-promoting behaviors for adolescents and young adults.

• Discuss the prevalence of adolescent violence and strategies to deal with aggressive behavior.

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/McKinney/mat-ch

Adolescence spans ages 11 to 21 years, although the developmental tasks of early adolescence, as well as the beginning stages of sexual maturation, may overlap with the school-age years. Adolescence is a time of change for teenagers and their families, a transition from childhood to adulthood. During this transition period, dramatic physical, cognitive, psychosocial, and psychosexual changes take place that are exciting and, at the same time, frightening.

Healthy People 2020 (United States Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2010) objectives address many areas of adolescent health, some of which are contained in a new topic area specifically directed toward adolescents. These areas include access to comprehensive health care and education about, and practice of, appropriate reproductive health practices, violence reduction, and decrease in risk factors.

Adolescent Growth and Development

The adolescent tries out many new roles during this time as part of the important developmental task of identity formation. The peer group is of the utmost importance as adolescents experiment with new roles outside the confines of the family unit. When identity formation is complete, the young adult is emancipated from the family and establishes independence.

The rapid rate of physical growth during adolescence is second only to that of infancy. Adolescents come in many shapes and sizes, and the changes that take place during the teen years are obvious and dramatic. With physical changes come the development of secondary sexual characteristics and an intense interest in romantic relationships. In general, adolescents move from the same-sex friendships of childhood to the capacity for intimate, long-lasting relationships as young adults. Sexual orientation and gender identity are often recognized during adolescence as the teenager engages in exploration and self-discovery.

Both parents and adolescents need the nurse’s support and guidance in understanding and facilitating health-promoting behaviors. Nurses can assist adolescents and their families in the areas of health promotion, disease prevention, and management of common problems by using effective communication strategies, knowledge of normal growth and development, anticipatory guidance, and early identification of potential problems.

Physical Growth and Development

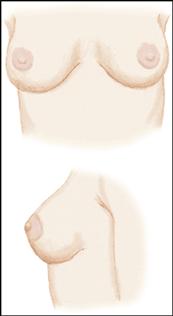

Physical development during the adolescent years is characterized by dramatic changes in size and appearance. Girls experience budding of the breasts followed by the appearance of pubic hair. Approximately 1 year after breast development, height increases rapidly until it reaches its peak (peak height velocity [PHV]). Growth in height in girls typically ceases 2 to 2½ years after menarche.

Boys also experience physical changes, but those changes are not as obvious as in girls. Boys first experience testicular enlargement, followed in approximately 1 year by penile enlargement. Pubic hair usually precedes the growth of the penis. The growth spurt in boys occurs later than it does in girls, beginning between ages 10½ and 16 years and ending between 13½ and 17½ years. Growth continues at a much slower pace for several years after the spurt but usually ceases between 18 and 20 years of age.

Muscle mass increases in boys, and fat deposits increase in girls. Because of greater muscle mass, fully developed adolescent boys tend to be larger and stronger than adolescent girls.

Psychosexual Development, Hormonal Changes, and Sexual Maturation

The physical development, hormonal changes, and sexual maturation that occur during adolescence correspond to Freud’s final stage of psychosexual development, the genital stage (Freud, 1960) (see Chapter 5). The genital stage begins with the production of sex hormones and maturation of the reproductive system. Sexual tension and energy are manifested in the development of sexual relationships with others, and sexual gratification is sought. Freud’s theory suggests that personality development is closely related to psychosexual development, with an emphasis on aggressive and sexual impulses as determining factors of personality. Freud’s theories about male dominance, sexual repression, and the Oedipus and Electra complexes make the psychosexual theory of development highly controversial even today.

Girls generally reach physical maturation before boys with the onset and establishment of menstruation (menarche). Menarche usually occurs between ages 9 and 15 years, however recent evidence suggests that the initiation of pubertal development (Tanner 2) is occurring at an earlier age than previously thought (Biro, Galvez, Greenspan, et al., 2010). Biro et al. (2010), in a study of pubertal development in a sample of more than 1200 girls ages 7 to 8 years, found that by 8 years of age, 18.3% of white, 42.6% of non-Hispanic Black, and 30.4% of Hispanic girls had attained Tanner 2 breast development. Reasons for earlier maturity are uncertain, but may include genetic influences, elevated body mass index (BMI), exposure to environmental chemicals, diet, and racial predisposition (Biro, Galvez, Greenspan, et al., 2010). Most young women achieve reproductive maturity 2 to 5 years after the start of menstruation. During the 2 to 5 years before reproductive maturity, the female sex hormones gradually increase, ovulation occurs more frequently, and menstrual periods become more regular.

Ultimately, diet, exercise, and hereditary factors influence adolescents’ height, weight, and body build. The earlier onset of puberty has implications for the timing of sex education programs and anticipatory guidance. It also has implications for health issues, such as breast cancer, that have hormonal components.

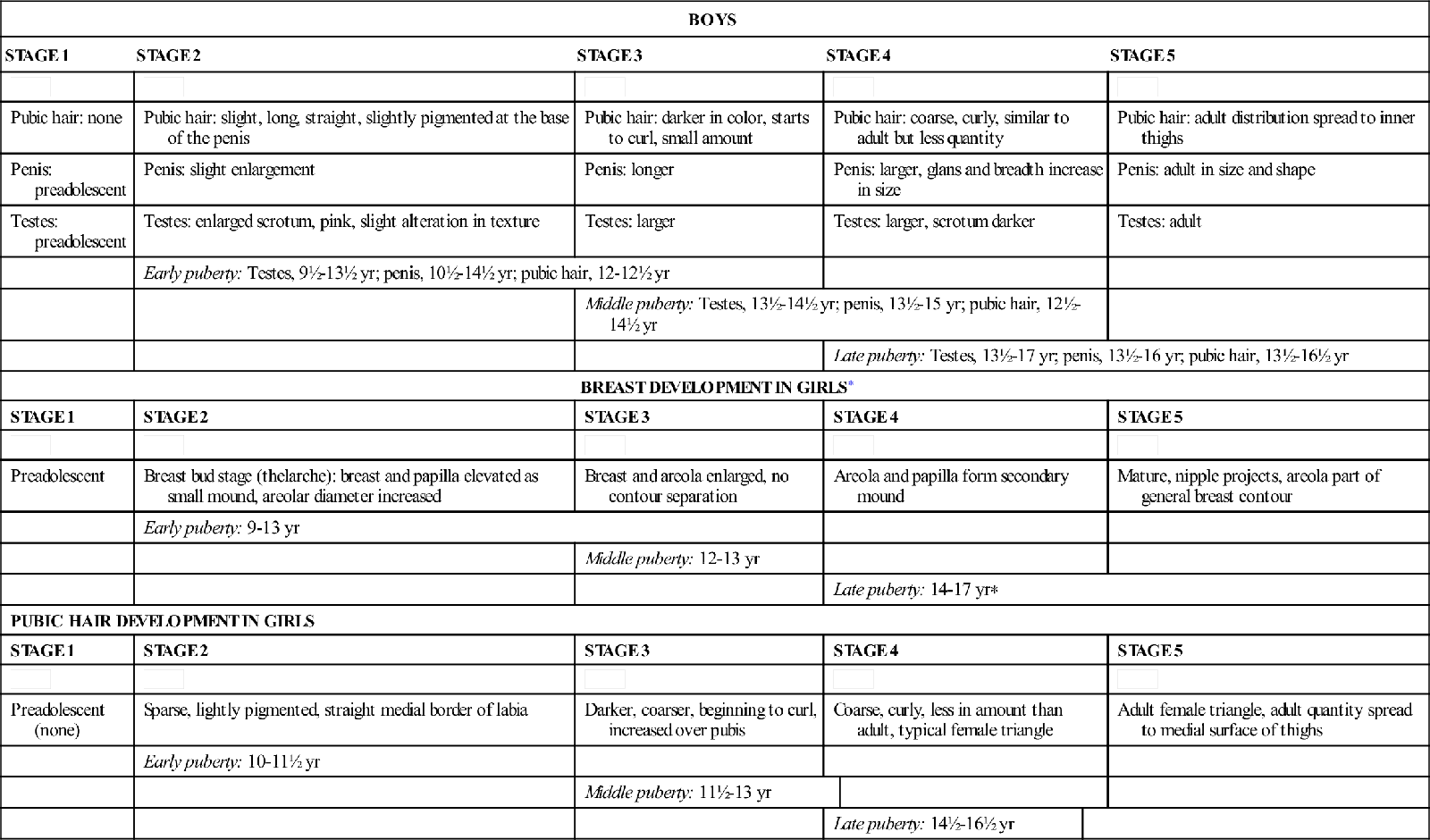

The physical growth of boys and girls is directly related to sexual maturation and occurs in a relatively predictable sequence. The secretion of sex hormones—estrogen in girls and testosterone in boys—stimulates the development of breast tissue, pubic hair, and genitalia. Hormonal secretion at the time of puberty is the result of a complex regulatory process among the environment, the central nervous system, the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland, the gonads, and the adrenal glands. Puberty is a biologic process that brings about PHV, or the “growth spurt,” the changes in body composition, and the development of primary and secondary sexual characteristics in both sexes. Although variable in both sexes, the PHV occurs at approximately age 12 years in girls and age 13½ years in boys. Table 9-1 describes five distinct stages in a sexual maturity rating (SMR) based on breast and pubic hair development in girls and genital and pubic hair development in boys and includes approximate age ranges for early, middle, and late puberty (Tanner, 1962). The beginning Tanner stages frequently occur in the school-age child, and Tanner stages 3 to 5 occur in adolescence.

TABLE 9-1

SEXUAL MATURITY RATING (SMR): TANNER STAGES OF ADOLESCENT SEXUAL DEVELOPMENT

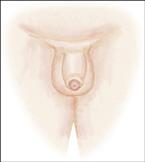

| BOYS | ||||||

| STAGE 1 | STAGE 2 | STAGE 3 | STAGE 4 | STAGE 5 | ||

|  |  |  |  | ||

| Pubic hair: none | Pubic hair: slight, long, straight, slightly pigmented at the base of the penis | Pubic hair: darker in color, starts to curl, small amount | Pubic hair: coarse, curly, similar to adult but less quantity | Pubic hair: adult distribution spread to inner thighs | ||

| Penis: preadolescent | Penis: slight enlargement | Penis: longer | Penis: larger, glans and breadth increase in size | Penis: adult in size and shape | ||

| Testes: preadolescent | Testes: enlarged scrotum, pink, slight alteration in texture | Testes: larger | Testes: larger, scrotum darker | Testes: adult | ||

| Early puberty: Testes, 9½-13½ yr; penis, 10½-14½ yr; pubic hair, 12-12½ yr | ||||||

| Middle puberty: Testes, 13½-14½ yr; penis, 13½-15 yr; pubic hair, 12½-14½ yr | ||||||

| Late puberty: Testes, 13½-17 yr; penis, 13½-16 yr; pubic hair, 13½-16½ yr | ||||||

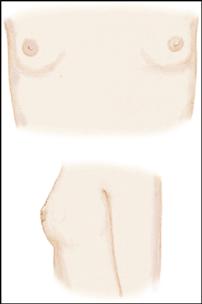

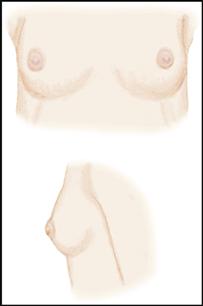

| BREAST DEVELOPMENT IN GIRLS∗ | ||||||

| STAGE 1 | STAGE 2 | STAGE 3 | STAGE 4 | STAGE 5 | ||

|  |  |  |  | ||

| Preadolescent | Breast bud stage (thelarche): breast and papilla elevated as small mound, areolar diameter increased | Breast and areola enlarged, no contour separation | Areola and papilla form secondary mound | Mature, nipple projects, areola part of general breast contour | ||

| Early puberty: 9-13 yr | ||||||

| Middle puberty: 12-13 yr | ||||||

| Late puberty: 14-17 yr∗ | ||||||

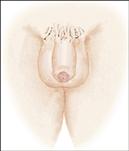

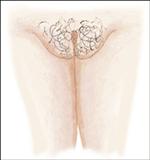

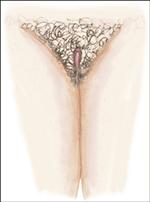

| PUBIC HAIR DEVELOPMENT IN GIRLS | ||||||

| STAGE 1 | STAGE 2 | STAGE 3 | STAGE 4 | STAGE 5 | ||

|  |  |  |  | ||

| Preadolescent (none) | Sparse, lightly pigmented, straight medial border of labia | Darker, coarser, beginning to curl, increased over pubis | Coarse, curly, less in amount than adult, typical female triangle | Adult female triangle, adult quantity spread to medial surface of thighs | ||

| Early puberty: 10-11½ yr | ||||||

| Middle puberty: 11½-13 yr | ||||||

| Late puberty: 14½-16½ yr | ||||||

∗Breast and pubic hair development may continue into late adolescence and may increase with pregnancy.

Modified from Tanner, J. M. (1962). Growth at adolescence (2nd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; Marshall, W. A., & Tanner, J. (1969). Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 44(235), 291-303. Modified with permission from Blackwell Scientific Publications and the BMJ Publishing Group.

In boys, puberty is considered delayed if testicular enlargement or pubic hair development has not occurred by age 14 years. Absence of breast budding or pubic hair development in girls by 13 years is reason for referral. Some of the more common causes of delayed puberty are chronic illnesses, malnutrition, extreme exercise, and hypothyroidism.

Female Sexual Maturation

Sexual maturation in girls begins with the appearance of breast buds (thelarche), which is the first sign of ovarian function. Thelarche occurs at approximately age 8 to 11 years and is followed by the growth of pubic hair. The PHV is reached during thelarche, usually in Tanner stage 2 or 3. Linear growth slows, and menarche begins approximately 1 year after the PHV. As pubic hair increases in amount and becomes dark, coarse, and curly, axillary hair develops and the apocrine sweat glands reach secretory capacity in Tanner stage 3 or 4. Frequent showers and deodorants become important to the adolescent. With increasing hormonal activity, girls develop a more adult body contour. As breasts mature, the nipples project more, and the pubic hair extends to the medial thighs; the young female is estimated to be at Tanner stage 5. Ovulation may be established, and conception can occur.

Male Sexual Maturation

The first sign of pubertal changes in boys is testicular enlargement in response to testosterone secretion, which usually occurs in Tanner stage 2. Slight pubic hair is present, and the smooth skin texture of the scrotum is somewhat altered. As testosterone secretion increases, the penis, testes, and scrotum enlarge. The PHV usually occurs during Tanner stages 3 and 4, and the voice deepens and “cracks” as the cartilage in the larynx enlarges. Axillary hair develops, and the eccrine and apocrine sweat glands respond to stressful or emotional stimuli. Skin surface bacteria metabolize secretions from the apocrine glands, and body odor develops. Gynecomastia (male breast enlargement) occurs in approximately two thirds of young males during early adolescence and may be unilateral or bilateral (Ali & Donohoue, 2011). This phenomenon is often disturbing to boys, and they need considerable reassurance that the breast tissue will decrease over time. During Tanner stages 4 and 5, rising levels of testosterone cause sebaceous glands to enlarge, and excessive sebum may result in acne. The voice continues to deepen, facial hair appears at the corners of the upper lip and chin, and ejaculation may occur. Nurses need to provide anticipatory guidance to adolescent boys regarding involuntary nocturnal emissions of seminal fluid (“wet dreams”) and assure them that this occurrence is normal. By Tanner stage 5, genital maturation is complete, spermatogenesis is well established, facial hair is present on the sides of the face, and the male physique is adultlike in appearance. Gynecomastia significantly decreases or disappears, much to the adolescent male’s relief.

Motor Development

Adolescents often engage in various forms of motor activity, from aerobic exercise to football. Motor activities such as sports and dancing provide an outlet for the adolescent’s energy, as well as an opportunity for competition, teamwork, and social relationships. Large muscle mass increases in adolescents, and coordination of gross and fine muscle groups improves. With practice, adolescents become more adept at athletics and also at art, music, sewing, and other activities that require fine motor skills. The bones are not completely calcified until after puberty and are still fairly resistant to breaking in the young adolescent. Participants in sports activities should be grouped according to their size and their sexual maturity rating rather than their chronologic age. A small, thin, late-maturing boy is less capable of competing with an early maturing, muscular classmate, and injuries are more likely to occur if they are grouped together.

Nurses, particularly school nurses, may be helpful in assessing adolescents’ growth and development and counseling them about sports activities in which they can succeed rather than those in which they will meet with physical and psychological failure. Adolescents should have a yearly physical examination if participating in high school athletics (Box 9-1); the school nurse keeps documentation of this matter. Because it is generally superficial, the school sports examination should not substitute for the recommended complete adolescent physical examination with counseling.

The development of the cardiovascular pump plays an essential role in the adolescent’s participation in gross motor activities. Cardiopulmonary capacity increases during adolescence and is relatively mature in the late adolescent. The cardiovascular pump is not as efficient in young adolescents, whose lungs are smaller. Adolescents generally cannot run as fast or as long as young adults. The athlete’s aerobic power, body composition, joint flexibility, and strength of skeletal muscles determine physical fitness.

Cognitive Development

Cognitive development influences every aspect of adolescent psychosocial development. Cognition moves from concrete to abstract thinking during the three phases of adolescent development. According to Piaget (1969), formal operations, or abstract thinking, characterize the last stage of cognitive development. Early abstract thinking encompasses inductive and deductive reasoning, the ability to connect separate events, and the ability to understand later consequences. Abstract thinking in late adolescence is increasingly logical, and young adults are capable of using scientific reasoning, understanding complex concepts, and using analytic methods. Because of logical reasoning, adolescents are able to differentiate between others’ perceptions and their own and to view social situations from a societal perspective.

In a review of adolescent cognitive development, Cromer (2011) states that the brain is still maturing during adolescence, and this maturational process affects cognitive and emotional processing. Increased myelinization of neurons, along with maturation of the superior temporal gyrus and the prefrontal cortex facilitate impulse control, decision-making skills, ability to understand consequences of alternative actions and prioritization. This allows for increased organization and problem-solving skills, as well as critical thinking. Cromer (2011) also states that possible hormonal influences heighten emotional sensitivity and intensity, which affects adolescent stress and risk-taking behavior. The implications of this finding for nurses are especially apparent for health teaching. Adolescents think in different ways than adults. For example, sex education for ninth graders is quite different from that for college freshmen or adolescents with their first full-time jobs. The college freshman should be able to appreciate the later consequences of sexual behavior, whereas the young adolescent is focused on the here and now. For example, one should ask the ninth grader and the college freshman how an unwanted baby will affect their lives, and compare their answers.

For a variety of reasons (including, for example, poor comprehension ability, lack of education, and chronic substance abuse), some older adolescents remain concrete thinkers. Nurses and educators need to know their audiences and address them appropriately. Nurses may need to help parents learn how to communicate with their teens appropriately. Counseling a group of adolescent substance abusers may be ineffective if the consequence of their behavior is tied to the future when their thinking is in the present. A professional approach to communicating with teens includes the following:

• Know adolescent development; consider how a teen will look to peers.

• Be open to their ideas and opinions and willing to negotiate choices.

• Listen nonjudgmentally, keeping criticism to a minimum.

• Encourage problem solving and mutual decision making.

• Be an advocate, but do not take sides against a parent.

Sensory Development

Adolescents’ eyes and ears are fully developed, and with the exception of refractive errors and occasional minor infections of the eyes, ears, and sinuses, the sensory system remains quite healthy. Myopia occurs in early adolescence, between ages 11 and 13 years, often requiring frequent changes in corrective lenses.

Because of increased participation in competitive sports and outdoor activities, eye injuries are common in adolescence. Boys are more prone to eye injuries than are girls. Adolescents should always be required to wear safety or protective equipment when competing in sports or participating in any activity that may compromise eye safety.

Language Development

With the acquisition of formal operational thought and adequate intellectual capacity, adolescents are able to understand abstract concepts, process complex thoughts, and express themselves verbally. Adolescents who read extensively are generally more articulate and have a larger vocabulary than those who do not. Social development and self-confidence play a significant role in how well adolescents express themselves verbally to others. Shy, introverted adolescents may have difficulty speaking to a group or members of the opposite sex but may write expressively. Conversely, extroverted, social adolescents who have no trouble with verbal expression may lack the reading and writing skills for effective written communication.

Computer technology has added to the adolescent’s avenues for creative expression. Adolescents are capable of expressing ideas in symbols and abstract concepts, and many enjoy interpreting or even developing complex computer programs. Computers have a symbolic language of their own that some adolescents find fascinating. Teens may become more proficient with computer technology than their parents. In addition to teaching teens basic computer literacy, many high schools have computer clubs where students who excel in computer languages share ideas and knowledge of computer information systems. Because of safety concerns with young adolescents using the Internet, parents need to monitor computer use and investigate whether parental controls available through some Internet access companies are appropriate for their child.

Electronic or digital vehicles for communication have impacted language communication as well. Social media websites, e-mail, telephone text messaging, instant messaging, blogs, and Twitter all contribute to abbreviated communication techniques, which eliminate not only grammar and sentence construction, but also word construction (e.g., using ur, for you are).

Communicating with adolescents sometimes presents a challenge to parents and other adults. Although adolescents are capable of verbal expression, they are also intensely private and may not wish to divulge their thoughts and feelings to others. Developmentally, the verbally expressive 12-year-old may turn into a relatively uncommunicative 14-year-old. Conflict with parents increases tension in communication (see Parents Want to Know box: Communicating with Adolescents).

Psychosocial Development

Identity formation is the major developmental task of adolescence; other tasks include the formation of a sexual and vocational identity and the ability to emancipate oneself from the family or become independent (Figure 9-1). Energy is focused within the self, and the adolescent is described as egocentric or self-absorbed. Frustrated parents often describe teenagers during this phase as self-centered, lazy, or irresponsible. In fact, they just need time to think, concentrate on themselves, and determine who they are going to be. Erikson (1968) described the conflict of this phase of psychosocial development as identity formation versus role confusion; this phase corresponds to Freud’s genital stage of psychosexual development (see Chapter 5 for information on developmental theories).

Relationships with the opposite sex are more mature by late adolescence. Late adolescents have more realistic expectations of both themselves and those who are important to them. They devote many hours and much anxious thought to making events, such as prom night, memorable for a lifetime. Some adolescents may be left out because they are unpopular or shy or do not have the financial resources to participate in these special events. With the freedom driving brings to the adolescent, comes responsibility. The adolescent’s inexperience and risk-taking behaviors can be a lethal combination. Computers in school and in many homes provide the adolescent with opportunities for learning, creative expression, communication, and entertainment. Adolescents often enjoy “surfing” the Internet, which can provide them with information not readily available locally. Parents must monitor their adolescent’s computer connections, however, for these networks sometimes allow access to people and activities that conflict with family values. Although teens often have friends of both sexes, they are more comfortable sharing their hopes, dreams, secrets, and even embarrassing incidents with friends of the same sex.

In the transition period from childhood to adulthood, adolescents try new roles and experiment with the environment until they find a role that fits. The phase of experimentation has been termed the moratorium, meaning a period of delay granted to someone not yet ready to make more than a tentative commitment (Erikson, 1968). The adolescent’s changing interests from year to year illustrate the lack of commitment. Parents may invest in expensive sports equipment or a musical instrument only to find it abandoned after a short time.

The peer group plays an essential role in adolescent identity formation. Teenagers take their cues on appearance, social behavior, and language from the peer group. The peer group serves as a safe haven as adolescents emotionally move away from the family and struggle to determine who they are. The peer group validates acceptable behavior, and teenagers feel secure in trying on new roles with peer-group approval. Teens frequently spend all day with friends in school and all evening rehashing the day’s events over the phone or through postings on social media websites (Box 9-2). Changes in the adolescent’s body image, psychosocial development, and peer group acceptance are closely related. Early and middle adolescents are particularly audience conscious and feel that they are the focus of everyone’s attention. A bad hair day or a blemish may throw the adolescent into despair. Clothing, hairstyles, and material possessions that are accepted by the group become the most important. Nurses counsel parents to negotiate choices with teens but always consider how peers will judge the child.

Early adolescence and middle adolescence are the periods when teens are prone to gang formation and activities. Peer modeling and peer acceptance, being of the utmost importance, lead some adolescents to form gangs that provide a collective identity and give them a sense of belonging. Peer pressure, companionship, and protection are the most frequently reported reasons for joining gangs, particularly those associated with violent or criminal acts.

Early and late adolescence have marked developmental differences. Each age-group has unique reactions to the developmental tasks, which are influenced by the adolescent’s cognitive thinking. According to Piaget (1969), adolescent cognition is characterized by the transition from concrete operational thought to formal operational thought, the ability to think logically and use deductive and abstract reasoning (in addition to this chapter, see Chapters 5 through 8). The acquisition of formal operational thinking allows the adolescent to recall past experience and to apply knowledge to the future by drawing logical consequences from a set of observations. Adolescents are capable of using abstract symbols such as those derived from higher-order mathematics, making and testing hypotheses, and considering and arguing philosophic issues. Problem-solving and decision-making skills become more highly developed, although adolescents may still be conflicted about idealism versus reality.

Early Adolescence

The early adolescent (11 to 14 years) has intense feelings about body image and the many physical changes taking place. Less confident with members of the opposite sex, early adolescents tend to group together and have best friends of the same sex. One has only to visit the local mall or a movie theater to see groups of young teens of the same sex, observing but rarely speaking to groups of the opposite sex.

The early adolescent is quite egocentric and may move from obedience to rebellion regarding parental authority. Parents are often shocked by the sudden turn of events and are hurt by the teen’s rejection. Providing parents with anticipatory guidance regarding age-specific developmental changes is a primary nursing function. For example, the happy-go-lucky 11-year-old may turn into the shy, self-absorbed 12-year-old who seems comfortable only in the presence of friends. Young teens, who are developmentally egocentric, fail to differentiate between how others see them and their own mental preoccupations, thinking everyone is as obsessed with them as they are with themselves. Elkind (1993) describes this phenomenon as a reaction to the imaginary audience. The belief in the imaginary audience is probably why young teens are so self-conscious; they believe everyone is critical of them, and indeed teens are quite critical of one another, especially those who are different. Self-conscious behavior may also be the result of the physical and emotional transition to middle adolescence. The early adolescent is losing the familiar role of the child but does not yet feel comfortable with the role of the adult. Ambivalence toward independence is common, and the teen who feels too grown up for a good-night kiss from a parent still falls asleep with a favorite teddy bear.

Elkind (1993) believes that because young teens are so audience conscious, they see themselves as unique and tell themselves a “personal fable” that supports feelings of invulnerability. They believe bad things will happen to others but not to them. Adolescent suicide attempts, for example, serve as a dramatic message to others, but young teens often do not realize the final consequences of their actions.

Middle Adolescence

Middle adolescence (15 to 17 years) is often described by parents as the most frustrating period of adolescent development. The real audience gradually replaces the imaginary audience, and teens become even more introspective and narcissistic. Conformity to peer-group norms becomes even more important, and conflicts between teenagers and parents often escalate. Testing of limits, sulky withdrawal, and overt rebellion may occur over conflicts regarding curfews, friends, activities, appearance, cars, and money. The adolescent may feel more secure by associating with or becoming a member of a gang (Box 9-3). Nurses counsel parents to negotiate choices when possible and set limits that are perceived as reasonable by the adolescent. Consistent discipline and structure actually make adolescents feel more secure and assist them with decision making. With parental guidance, adolescents are able to make decisions that will result in desirable outcomes. Adults must keep in mind that middle adolescents are impulsive and impatient, however. Parental concern may be seen as interference rather than guidance and may be met with resistance and resentment.