The Child with a Respiratory Alteration

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

• Outline nursing care for a child with allergies to inhalants.

• Develop guidelines for the home care of a child with an acute respiratory alteration.

• Identify common triggers of asthma symptoms.

• Apply measures that can be taken to prevent and treat asthma episodes.

• Identify teaching needs for children with asthma and their families.

• Describe the nursing care of the child with cystic fibrosis.

• Describe the correct method of administering and evaluating tuberculosis skin tests.

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/McKinney/mat-ch

Respiratory Illness in Children

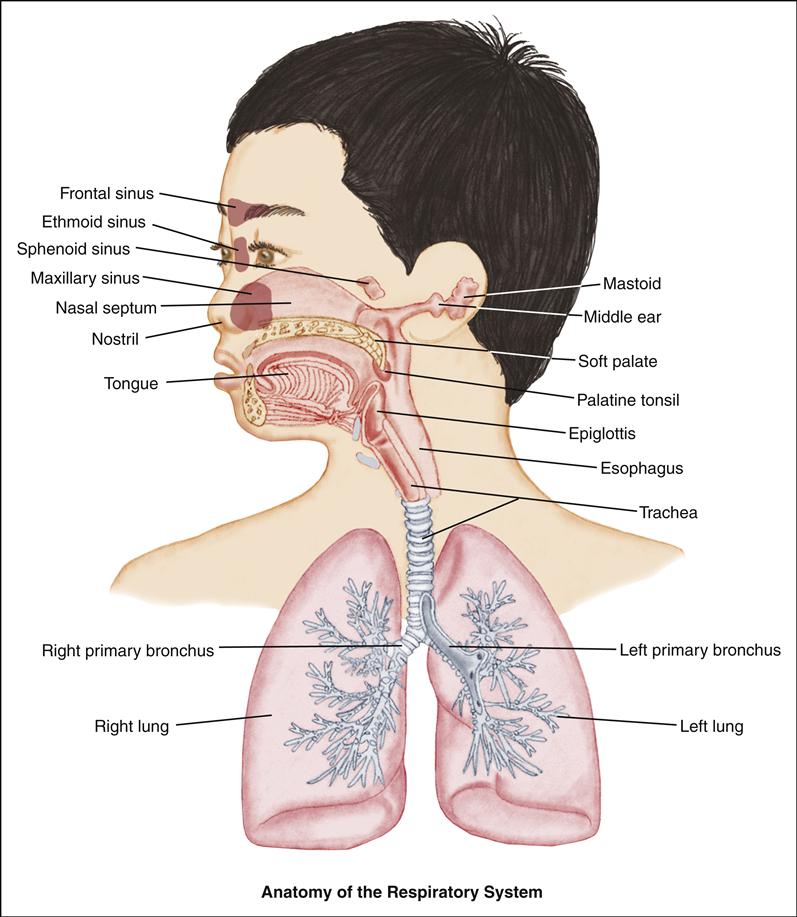

Respiratory alterations are the most common causes of illness in the infant and child. Upper respiratory disorders affect the ears, nose, pharynx, and larynx; lower respiratory disorders include those disorders that involve the trachea, bronchi, and lungs.

Infants and children younger than 3 years are at greater risk than older children and adults for development of respiratory infections because of their immature immune systems, smaller upper and lower airways, and underdeveloped supporting cartilage. Although most respiratory infections are self-limiting, in infants and young children respiratory distress can occur quickly as mucus and edema obstruct their small airways.

Parents should be taught preventive measures, including adequate rest, optimal nutrition, and good hygiene, with an emphasis on hand hygiene. Even with the most careful hygiene and preventive practices, however, most children will have some type of respiratory infection each year. School nurses often see children with respiratory problems in the school health office and may be the primary health care providers for these children.

Most children can be cared for at home by their parents and do not need hospitalization. Those children who are hospitalized are being discharged from the hospital earlier in their recovery than in the past. The current health care environment underlies the need for nurses to teach parents appropriate home care techniques, including careful observation and recognition of signs that indicate the need to contact health care providers. Parents, especially first-time parents, often are frightened by the sudden onset of respiratory symptoms, which may indicate a severe problem. Teaching them the signs and symptoms of serious illness will help them develop appropriate decision-making skills.

Children with chronic conditions have many special needs, and the child with a chronic respiratory disease is no different. Medications and treatments become a way of life for many of these children. Their activity level is often altered, and some may have a shortened life span.

Children with chronic respiratory conditions are now becoming adults with those same conditions. As advances in treatment modalities are made and children with these conditions are living longer, the transition to adult care becomes a necessity.

The nurse plays an important role in the care of the child with a chronic respiratory disease. Beyond giving acute care to the hospitalized child, the nurse must coordinate and facilitate the child’s long-term care. Because of advances being made in the treatment of chronic pediatric respiratory conditions, the treatment and care of children affected by these disorders are constantly changing and improving, requiring the nurse to stay current in these areas.

Allergic Rhinitis

Allergic rhinitis is an inflammatory disorder of the nasal mucosa. It is usually seasonal, recurrent, and triggered by specific allergens (see Chapter 42). It is sometimes referred to as seasonal allergic rhinitis or hay fever. Some children have symptoms year round (perennial allergic rhinitis).

Etiology and Incidence

Agents that commonly cause allergic rhinitis include dust mites; feathers; animal dander; mold spores; and pollens of trees, grasses, and weeds. There is usually a family history, similar to that seen in individuals with atopic dermatitis and asthma. Unlike atopic dermatitis, however, allergic rhinitis does not predispose to the development of asthma.

The onset of allergic rhinitis usually occurs during childhood but rarely before age 2 years. It is estimated that 20% to 40% of children have this type of allergic response (Milgrom & Leung, 2011).

Manifestations

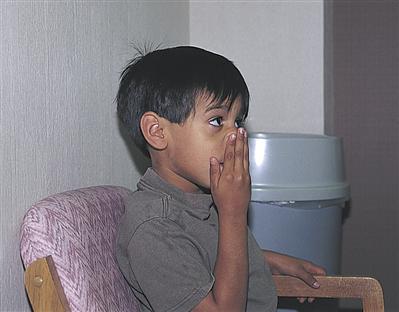

The classic symptoms of allergic rhinitis are clear rhinorrhea, associated with itching of nose, eyes, ears, and palate, and paroxysmal sneezing. Additional signs and symptoms include the “allergic salute”—an upward rubbing of the nose with the palm of the hand, which can leave a crease below the bridge (Figure 45-1); allergic shiners—dark circles under the eyes from congestion and edema; dry lips from mouth breathing; pale, boggy nasal mucous membranes; and nasal obstruction. Children with allergic rhinitis have symptoms as long as they are exposed to the allergen.

It is important to distinguish allergic rhinitis from viral nasopharyngitis (the common cold), which is usually caused by a rhinovirus and is spread by droplet or by contact with contaminated items. Usually children with nasopharyngitis have the associated symptoms of sore throat, fever, cough, and fatigue. The condition is self-limiting and usually resolves within 2 weeks. The quality of the nasal discharge in children with nasopharyngitis often changes from clear to cloudy or yellow. Management is supportive. Because young infants are obligatory nose breathers, the infant’s blocked nasal passages can be relieved with instillation of normal saline solution drops followed by gentle bulb suction.

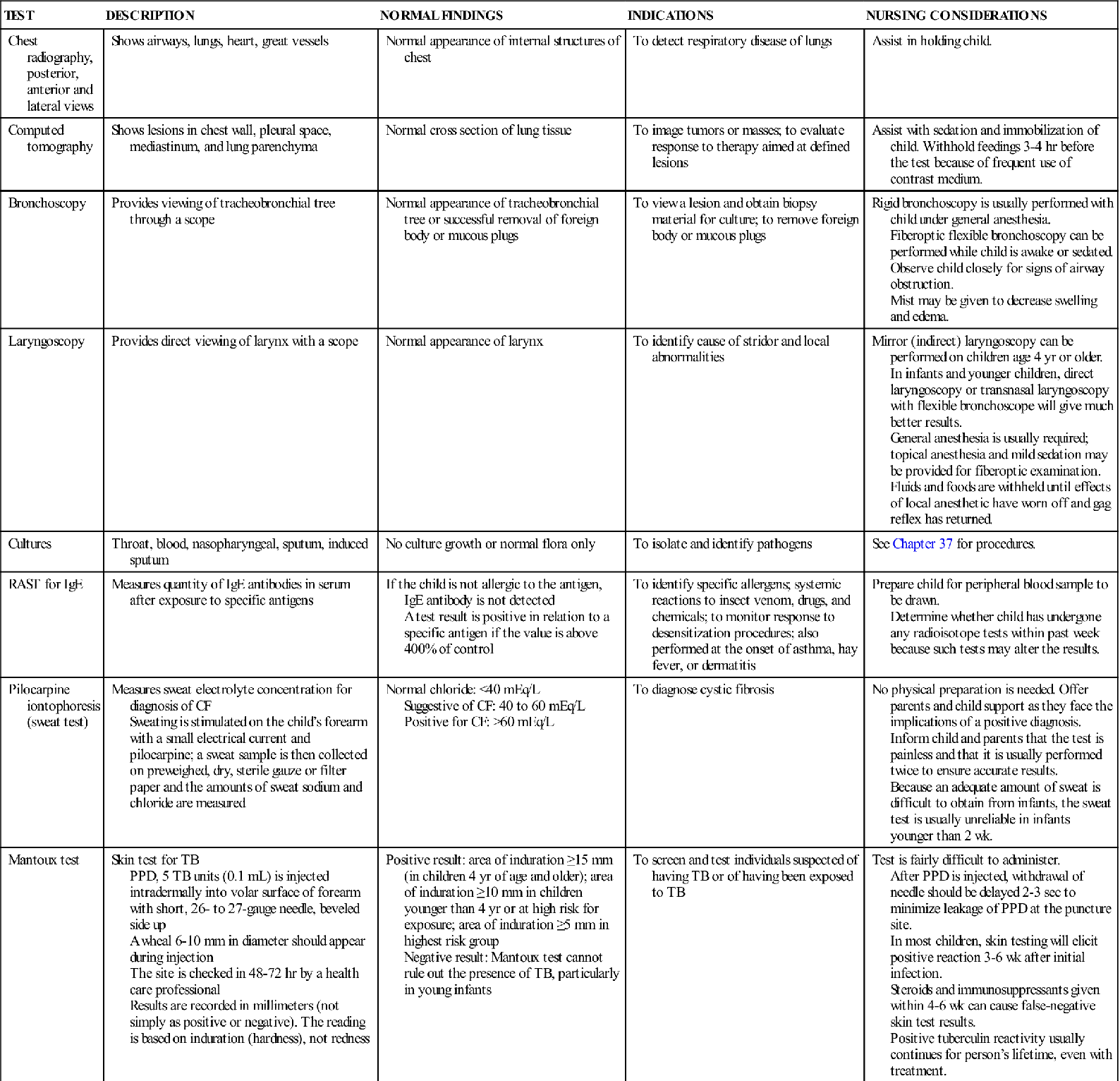

Diagnostic Evaluation

A thorough personal and family history usually elicits a description that suggests an allergic rather than infectious pattern. The nasal smear may demonstrate eosinophils. Allergy skin testing is done if signs and symptoms continue after treatment with medication. The radioallergosorbent test (RAST) is used only when skin testing is difficult because of generalized dermatitis, the child is very young, or the child is too ill for skin testing. A complete blood cell count might reveal elevated eosinophils, a finding associated with allergic manifestations.

Therapeutic Management

The treatment of choice is to eliminate the allergen from the child’s environment; however, complete elimination may be difficult in children (Turner & Kemp, 2010). When this is impossible, as in the case of pollen in the air, medication can control symptoms.

Antihistamines or intranasal corticosteroids may be effective in treating allergic rhinitis. Antihistamines are most effective when given before or very early in an allergic episode. Because they can cause drowsiness, they should be given at night. Some of the newer antihistamines (e.g., loratadine, cetirizine, fexofenadine) are long acting, have fewer side effects and require only one or two doses daily. They are prescribed according to the child’s age. Decongestants may be effective in relieving nasal congestion, but are not recommended in children. Decongestants have side-effect profiles that include insomnia, behavior problems, and even cardiac events; therefore, their use is no longer recommended (Turner & Kemp, 2010).

Short-term topical intranasal corticosteroids (e.g., fluticasone, mometasone, and budesonide) are highly effective and may be used as first-line therapy for children with allergic rhinitis (Milgrom & Leung, 2011; Turner & Kemp, 2010). It usually takes several days of treatment before the child feels the effects of topical corticosteroids.

Leukotriene inhibitors (e.g., montelukast [Singulair]) may be used in the treatment of allergic rhinitis, although results may be suboptimal. These medications have a good safety profile and seem to work well for children with both allergic rhinitis and asthma (Turner & Kemp, 2010).

Finally, immunotherapy (allergy shots) may be considered for children whose condition is not responsive to either environmental modification or medication. Immunotherapy involves injecting the child with progressively larger doses of the allergen in an effort to reduce the magnitude of the body’s allergic response. Injections are given once or twice a week until a maintenance dose is reached; monthly maintenance injections can continue for several years.

Nursing Considerations

Nursing care focuses on early identification of clinical signs and symptoms of allergic rhinitis and the therapeutic management of the condition. The nurse assesses and records the applicable history and helps the family identify allergens to which the child is sensitive. Once the allergens are known, the nurse counsels parents regarding administration of medications, environmental control, and immunotherapy as appropriate (see Patient-Centered Teaching: How to Implement Environmental Modifications). Allergies, including allergic rhinitis, can negatively affect quality of life and school performance—not only does allergic rhinitis impair cognitive function, but allergies are also one of the most common reasons for missed school days (Parker, Akinbami, & Woodruff, 2009).

Side effects of medications used to treat allergic rhinitis can further impair functioning. Drowsiness, the most common side effect of antihistamines, can usually be alleviated if the child takes the medication at night. Some children may have dry mucous membranes or excitability. Warm water or saline solution irrigations of the nasal passages can be used to moisten mucous membranes, soften crusted secretions, and wash out irritants. Saline solution can be mixed by adding ¼ teaspoon of salt to a cup of warm water. Saline solution nose drops are also available without prescription.

When specific allergens have been identified, they should be eliminated or controlled. During the pollen season, the child should stay indoors as much as possible and the windows should be kept closed if the house is air conditioned. After being outdoors, the child should shower and wash his or her hair to remove pollens from the body. Animals that have been outside may also be a source of contamination.

Receiving immunotherapy can be a traumatic experience for the child. It is often difficult for children to understand how an injection will help them. Allergy injections must be given in a physician’s office because the risk of an anaphylactic reaction to the allergy serum exists. Monitor the child closely (vital sign changes, difficulty breathing) for 20 to 30 minutes after the injection in case anaphylaxis develops. Keep emergency epinephrine ready.

Sinusitis

Sinusitis, although not itself a serious disorder, can lead to life-threatening complications. Inflammation and infection of the sinuses can be acute or chronic.

Etiology and Incidence

Acute sinusitis often follows an upper respiratory tract viral infection. Children with chronic sinusitis often have allergic rhinitis or otitis media with effusion (OME) as well. Hypertrophied adenoids, immune deficiencies, and foreign body obstruction in the nose also predispose one to sinusitis. Children with cystic fibrosis have a high incidence of sinusitis because of highly viscous mucus secretions and nasal polyps. The most common causative organisms are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and Staphylococcus aureus (Pappas & Hendley, 2011).

Sinus infections can occur in infancy as well as in childhood and are seen frequently in preschool and school age children as a result of group exposure to upper respiratory infection (Pappas & Hendley, 2011).

Manifestations

Sinusitis is characterized by signs and symptoms of a cold that do not improve after 14 days, low-grade fever, nasal congestion with purulent nasal discharge, halitosis, cough (which usually increases when the child is lying down), and headache, tenderness, and a feeling of fullness over the affected sinuses. Young children may become irritable. Occasionally, children have facial edema. Children with chronic sinusitis have many of the same symptoms except that the cough is chronic and the

headache is recurrent. The child’s sense of taste or smell may be impaired, and the child may be fatigued.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Sinus radiographs show mucosal thickening, opacification, and air-fluid levels in children older than 1 year. Sinus radiographs are of no value in younger children because of their small sinuses. Computed tomography is the diagnostic tool chosen most often for evaluation of sinus disease because it provides detailed anatomic information (Leo, Mori, Incorvaia, et al., 2009). Because of the thick bone of the maxilla in the anterior part of the face and the small size of the sinus, transillumination of the sinuses is not useful.

Therapeutic Management

Most cases of acute sinusitis are self-resolving and do not require antibiotics (Suhaili, Goh, & Gendeh, 2010). When a prescription is required, amoxicillin or amoxicillin–potassium clavulanate (Augmentin) is used most frequently (DeMuri & Wald, 2010). In addition to antibiotics, treatment includes analgesics, hydration, and the application of moist heat. The use of decongestants or antihistamines in the treatment of sinusitis should be avoided in children secondary to inefficacy and potential risks posed to children (DeMuri & Wald, 2010). Antihistamines may be used to treat allergy symptoms associated with chronic sinusitis, but they tend to impair sinus drainage by thickening secretions. Steroid nasal sprays may be used to reduce inflammation while avoiding the rebound effect of decongestant nose drops. Saline nasal washes may also be helpful (DeMuri & Wald, 2010). Surgical correction may be considered for children with chronic sinusitis who have not responded to antibiotic therapy, who have other chronic respiratory disease (e.g., cystic fibrosis), or who have anatomical abnormalities (Wu, Shapiro, & Bhattacharyya, 2009).

If orbital cellulitis develops, the child should be hospitalized immediately and parenteral antibiotic therapy begun (Pappas & Hendley, 2011).

Nursing Considerations

The nurse assesses the location of pain or fullness. Pain can occur in the forehead or over the cheek bones or upper teeth, or it may radiate to the top of the head. Inspect and palpate the face for edema, document any fever, and inspect the nose and throat for purulent discharge. The nasal mucous membranes are inspected for erythema and edema.

Nursing care focuses on teaching the parents antibiotic administration, comfort measures, how to monitor for response to treatment, and how to identify complications. Emphasize the importance of the child’s taking the antibiotics as prescribed. Sinus drainage is facilitated by increasing the child’s intake of clear fluids and by using a bedside humidifier.

Warm, moist compresses applied two or three times daily help decrease swelling and pain. Acetaminophen is given for fever and discomfort. Breathing warm mist in a hot shower or through hot, moist towels can help liquefy and mobilize nasal mucus, as can saline solution nose drops. The nurse teaches the parent to administer nose drops after the nasal passages have been gently cleaned. The amount, color, and consistency of nasal drainage should be noted and evaluated to determine whether the child is responding to treatment.

Carefully evaluate the child’s response to treatment and the development of complications. Advise parents to contact the physician promptly if symptoms become worse, if the child has any periorbital redness or edema, or if the child does not seem to be feeling better after 3 to 4 days.

Otitis Media

Otitis media is one of the most common illnesses of infancy and childhood. The term otitis media refers to effusion (fluid) and infection or blockage of the middle ear. Acute otitis media (AOM) is effusion and inflammation in the middle ear that occurs suddenly and is associated with other signs of illness. Otitis media with effusion (OME) refers to the presence of fluid behind the tympanic membrane without signs of infection. Otitis media with effusion often follows an episode of AOM and usually resolves in 1 to 3 months.

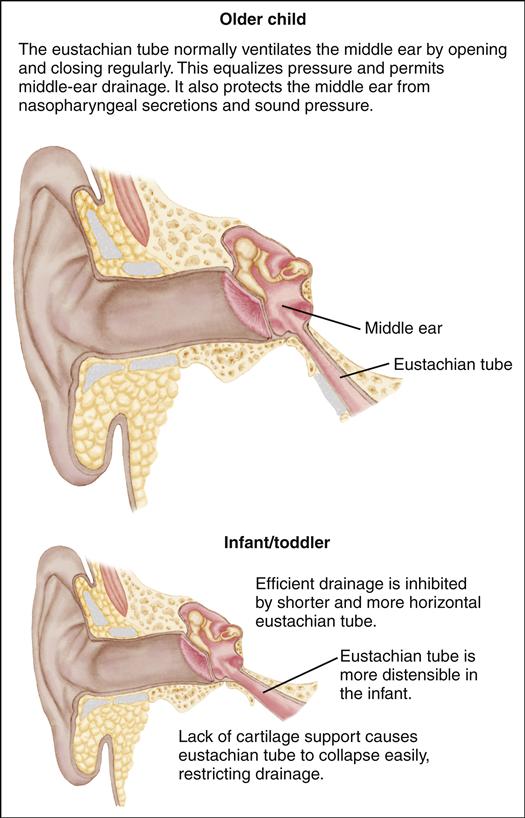

Etiology

The bacterial pathogens that usually cause AOM are S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, and M. catarrhalis (Coates, Thornton, Langlands, et al., 2008). Although viruses do not cause otitis media, they are thought to predispose the child to ear infection by altering host defenses and contributing to eustachian tube dysfunction. Allergies are also thought to precipitate otitis media.

Attendance at daycare centers may predispose children to otitis media. Infants younger than 1 year who attend daycare have a significant risk for acquiring AOM. Other risk factors include age (highest in 6- to 24-month-olds), ethnicity (higher in Native Americans, Alaskan and Canadian Inuit, and indigenous people of Australia), exposure to household cigarette smoke, pacifier use, and poverty (Kerschner, 2011).

Bottle feeding can contribute to ear infection because of the position of the infant during feeding. Reflux of formula into the eustachian tube from the nasopharynx occurs when the infant swallows while supine. Breastfeeding offers some protection from ear infection by providing maternal antibodies and by decreasing the incidence of allergy; also, the more upright position of the infant while nursing or bottle feeding may be protective against ear infection (Kerschner, 2011).

Incidence

The incidence of otitis media peaks between ages 6 months and 6 years, with most episodes occurring in children younger than 3 years. Most initial episodes occur at about age 6 months, when maternal antibody levels decline. Early onset of AOM (during infancy) increases the risk for recurrent episodes (Lasisi, Olayemi, & Irabor, 2008).

By the end of the third year of life, more than 80% of all children have had at least one episode of AOM (Kerschner, 2011). Most children younger than 5 years of age have two or three episodes of otitis media each year. Boys have a slightly higher incidence of otitis media than girls. The incidence of otitis media is highest in winter and spring and lowest in the summer months.

Manifestations

AOM is characterized by the following:

• Otalgia (earache); infants may pull their ears or roll their heads.

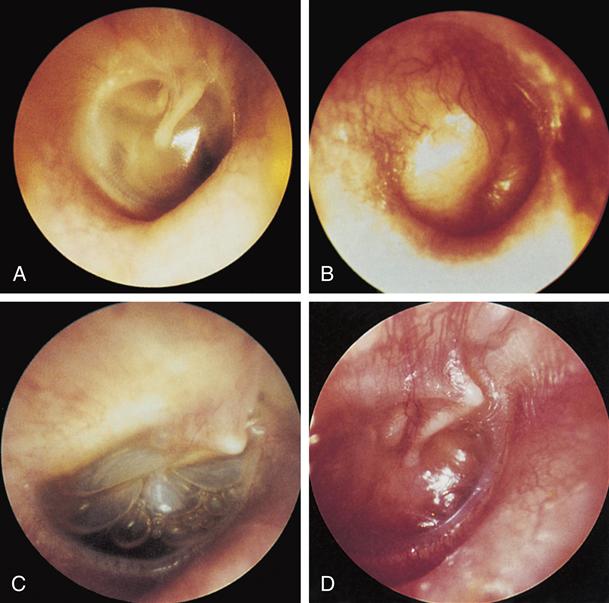

• A bulging, opaque tympanic membrane that usually looks red, with decreased mobility; diffuse light reflex; and obscured landmarks (Figure 45-2).

A, Normal right tympanic membrane and middle ear.

B, Acute otitis media: bulging right tympanic membrane. C, Otitis media with effusion: air-fluid level and bubbles visible through right retracted, translucent tympanic membrane.

D, Otitis media with effusion: severely retracted, opaque right tympanic membrane. (From Bluestone, C. D., & Klein, J. O. [1995]. Otitis media in infants and children [2nd ed.]. Philadelphia: Saunders.)

These signs and symptoms might also be accompanied by irritability, sleep disturbances, persistent crying in infants, fever, vomiting, anorexia, or diarrhea (especially in infants).

OME differs from AOM in that there are no signs of acute infection. The tympanic membrane appears retracted and either dull gray or yellow, and an air-fluid level or air bubbles may be visible through the tympanic membrane. The mobility of the tympanic membrane is decreased, and landmarks are distorted. Associated signs and symptoms can be subtle and can include the following:

AOM is considered to be persistent if the child experiences symptoms while being treated or within 1 month after treatment is complete. AOM is viewed as recurrent if the child

experiences more than three episodes over a 6-month period or four episodes in a year (Kotsis, Nikolopoulos, Yiotakis, et al., 2009).

Diagnostic Evaluation

The diagnosis of otitis media is based on the history of signs and symptoms and pneumatic otoscopy. In pneumatic otoscopy, a small puff of air is blown into the ear canal through the otoscope; the examiner can discern the appearance and mobility of the tympanic membrane. In addition to pneumatic otoscopy, tympanometry or tympanography can be used to confirm what was seen with the eye.

Therapeutic Management

The emergence of resistant organisms has created much discussion around the use of antibiotics to treat AOM because spontaneous resolution of the infection occurs in about 80% of children. In 2004, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) issued two policy recommendations regarding identification and management of AOM and OME in healthy children ages 2 months to 12 years (AAP, 2004; AAP Subcommittee on Otitis Media with Effusion, American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, 2004). Recommendations include the following:

• Accurate discrimination between AOM and OME before treatment decisions are made

• Adequate pain relief for children with AOM

• Use of amoxicillin at a dose of 80 to 90 mg/kg/day for 5 to 10 days when treatment is indicated

• Encouraging reduction of risk factors as a method for preventing AOM episodes

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree