The Child with a Genitourinary Alteration

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

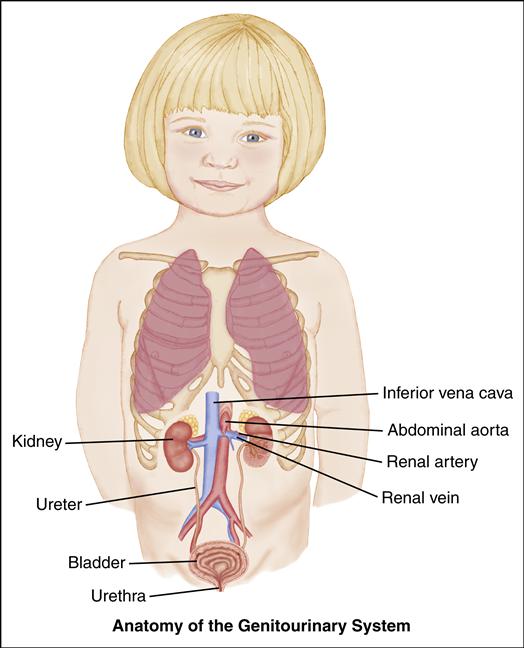

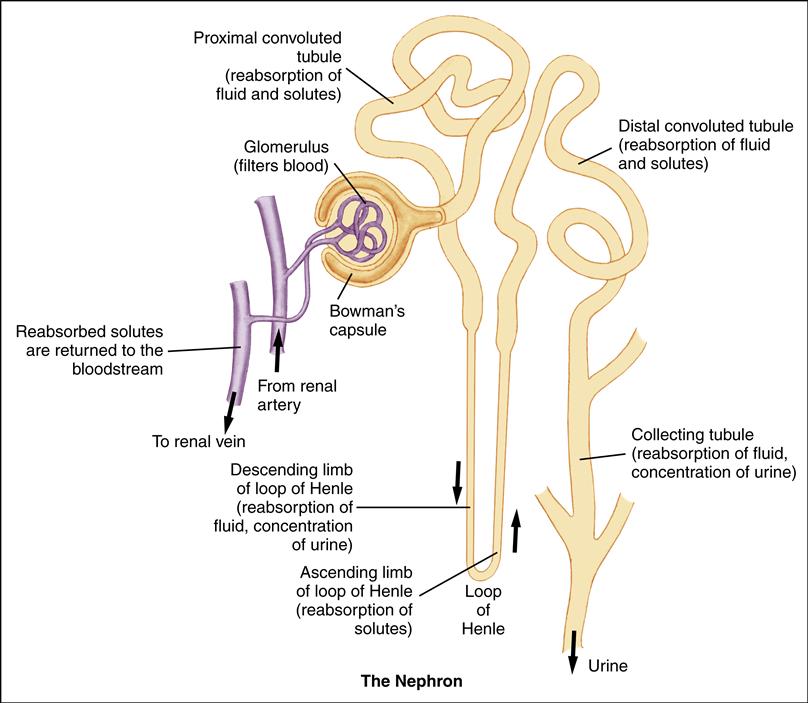

• Describe the anatomy and physiology of the infant’s and child’s genitourinary system.

• Discuss frequently seen alterations in the genitourinary system.

• Develop home care guidelines for the child with a genitourinary alteration.

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/McKinney/mat-ch

Enuresis

Children with difficulties in urinary control are defined as having enuresis. Nocturnal enuresis occurs at nighttime during sleep, whereas diurnal enuresis occurs during the day, or in waking hours. Primary enuresis is defined as a child never having experienced a period of dryness, whereas secondary enuresis occurs when a 6- to 12-month period of dryness has preceded the onset of wetting.

Etiology

Although there is no single cause for enuresis, several risk factors have been implicated. Physical factors include decreased bladder capacity, underlying urinary tract abnormalities, neurologic alterations, obstructive sleep apnea, constipation, UTI, pinworm infestation, diabetes mellitus, and voiding dysfunction. Emotional factors related to increased stress can contribute to secondary enuresis. These factors include family disruption, inappropriate pressure during toilet training, inadequate attention to voiding cues, and decreased self-esteem. Sexual abuse must be considered in a child with secondary enuresis.

Incidence

Primary nocturnal enuresis is common, affecting approximately 15% to 20% of children at 5 years of age and decreasing spontaneously thereafter (Elder, 2011f). It occurs more frequently in boys and in children with a family history of bed-wetting. Most children eventually outgrow bed-wetting without therapeutic intervention. Some children have diurnal (daytime) enuresis without nocturnal enuresis. Waiting until the last minute to void and not being able to access a bathroom quickly may be a factor in diurnal enuresis, but the main cause is an overactive bladder, a condition in which the child experiences bladder spasms or increased urgency (Elder, 2011f). Primary enuresis often resolves spontaneously.

Manifestations

Nocturnal Enuresis

Children with a continuing history of bed-wetting are not able to sense bladder fullness and do not awaken to void. Because physical maturation varies, nocturnal enuresis is not a matter for excessive concern unless the child is older than 6 years or has markedly decreased self-esteem.

Diurnal Enuresis

Children with urgency, frequency, and inappropriate wetting during the day may be seen rushing to the bathroom or tightly crossing their legs. Often these children cannot sit still and they exhibit a constant odor of urine.

Diagnostic Evaluation

The diagnosis of enuresis is based on the history and clinical symptoms. Urinalysis and urine culture can rule out possible UTI. Urine specific gravity and glucose measurement test for underlying diabetes. In addition, the child’s urine should be checked for excessive calcium, and a pinworm evaluation should be done to exclude infestation.

If the child has daytime enuresis, voiding dysfunction with urge incontinence is explored. Measures of urine flow and bladder capacity and bladder ultrasonography may be indicated. Children with UTIs should have a workup for underlying structural abnormalities.

Therapeutic Management

Treatment of primary nocturnal enuresis may begin with general interventions, such as explaining theories underlying the problem in terms the child can understand. The child is reassured that, with assistance, the problem can resolve. Commonsense approaches of limiting fluids after supper and voiding just before bedtime are encouraged. Diet modifications include avoiding extraneous sugar and caffeine intake after 4 PM, because these can act as bladder stimulants as well as diuretics (Elder, 2011f). Also, the child can be trained to use imagery; thinking about what a full bladder feels like and picturing waking up and going to the bathroom. This imagery is done as the child lies in bed before drifting off to sleep. The child should keep a record of the number of dry and wet nights to measure progress.

Reward systems assume that bed-wetting is a voluntary behavior and have had varying results for the child with primary nocturnal enuresis. The child may be given a roll of favorite stickers to mark the dry nights on the calendar. The family decides on a special reward or outing when the child has achieved a certain number of consecutive dry nights.

Behavioral conditioning with use of alarms has been successful in the older child with nocturnal enuresis. A device worn on the child’s pajamas contains a moisture-sensitive alarm. As the child starts to void, the alarm goes off, awakening the child. The alarm system may need to be used consistently over 15 weeks for resolution.

Desmopressin acetate (deamino-d-arginine vasopressin [DDAVP]) has also been helpful because of its antidiuretic effect. Desmopressin acetate is given as a tablet and is taken at bedtime. Pharmacologic treatment is not recommended for children under 6 years of age.

Voiding frequently to keep urine volume in the bladder low may benefit children who are affected by uninhibited bladder contractions during the day. The use of an anticholinergic such as oxybutynin chloride, which relaxes the smooth muscle of the bladder, can be helpful for children with diurnal enuresis related to underlying bladder instability or small bladder capacity. Biofeedback may also help children with diurnal enuresis, particularly those with dysfunctional voiding.

Nursing Care

The Child with Enuresis

Assessment

The nurse should obtain a full set of vital signs and assess the child and parent for their understanding of enuresis, including the interventions they have already tried. The nurse asks the child and parent to describe voiding and bowel elimination patterns, establishing whether the enuresis is primary or secondary. The nurse should also ask whether the child participates in social activities with peers, such as sleepovers, and whether the child is concerned about the problem of wetting. Therapy is much more successful for the older child than for the younger child, who may not be bothered by bed-wetting. The nurse should assist the child in obtaining a urine specimen. The physical examination includes assessment for signs of sexual abuse or visible genital abnormalities. It also is important to observe the lower spine for the presence of a dimple or hair tuft that might suggest spina bifida occulta (see Chapter 52).

Nursing Diagnosis and Planning

The nursing diagnoses and expected outcomes that apply to the child with enuresis and the child’s family are as follows:

Expected Outcome

The child will demonstrate positive self-esteem, as evidenced by a realistic description of the problem and positive self-statements.

Expected Outcome

The child will participate in age-appropriate activities such as sleepovers and overnight camp.

Expected Outcomes

The family will identify strengths and will describe positive problem-solving strategies.

Expected Outcome

The child will have no rashes or redness in the perineal area.

Interventions

Enuresis can be a frustrating problem for both the child and family. The nurse can help by providing them with correct information about causes and therapeutic approaches. It is important that the family choose the treatment that will best meet its needs. Follow-up to determine the effectiveness of treatment is essential because becoming dry can be a long process, and the nurse is instrumental in providing support to the child and family over the entire course of therapy.

Evaluation

• Is the child able to describe ways to manage the condition?

• Is the child showing an increased interest in peer activities?

• Is the family able to identify its strengths and demonstrate appropriate problem solving?

• Is the child having increased dry nights?

• Does the child’s skin remain intact and is it free from redness and rashes?

Urinary Tract Infections

Urinary tract infections (UTIs), which are characterized by the presence of bacteria in the urine along with systemic signs of infection, are commonly seen in children. In fact, UTIs result in significant morbidity in infants and children. These infections can have long-term complications that include renal scarring with decreased renal function, high blood pressure, and, rarely, end-stage renal disease (ESRD).

Etiology

UTIs, except in newborn infants, are caused by bacteria ascending from outside the urethra into the bladder and from there into the upper urinary tract. Bacteria in the blood, which seed in the kidney, can cause UTIs in newborn infants.

Fecal bacteria cause most UTIs. Escherichia coli are the bacteria implicated in 75% to 90% of all UTIs in girls (Elder, 2011d). Other bacteria known to cause UTIs are group B streptococci, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus species, Enterobacter species, enterococci, and Staphylococcus species. Viruses and fungi, specifically Candida species, can rarely cause infections.

The following conditions predispose the infant or child to UTI:

• Anatomic differences. Young girls have a short urethra, which expedites bacterial transit.

• UTIs in toddler-age girls are more frequent during toilet training, most probably as a result of urinary retention or incomplete bladder emptying (Elder, 2011d). It is generally accepted, however, that bacterial colonization of the prepuce of uncircumcised infants can increase the risk of UTI in infant boys younger than 1 year.

Incidence

The overall prevalence of UTIs in the United States is 3% to 5% in girls and 1% in boys. In girls, the first UTI generally occurs before 5 years of age with an increase in the number of cases seen during infancy and toilet training. For boys, most UTIs occur during the first year of life with a higher incidence in uncircumcised infants (Elder, 2011d). Symptoms of a UTI may be missed in children with coexisting gastrointestinal or respiratory symptoms, so UTI should be considered as a cause in any child with significant illness, especially if febrile (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence [NICE], 2007). It is important to diagnose UTIs quickly, as an ascending UTI can result in renal scarring. VUR is a frequently seen underlying anatomic abnormality in children with UTIs.

UTIs are more prevalent in white, Asian, and Hispanic children and less prevalent in African-American children (Shaikh, Morone, Lopez, et al., 2007). Breastfeeding has been found to significantly reduce the risk of UTIs in both boys and girls because of the protective factors observed in human milk that prevent microbial attachment to the mucosa (Marild, Hansson, Jodal, et al., 2004).

Manifestations

Clinical manifestations of UTI vary widely; factors include the child’s age, sex, underlying anatomic or neurologic abnormalities, and frequency of recurrence. Signs in the young child and infant are more vague and nonspecific. Fever (100.4° F [38° C]) without a known focus for infection in infants and young children 2 to 24 months of age suggests a UTI. Suprapubic tenderness may be an accompanying sign in an infant. Signs and symptoms in a verbal child include abdominal pain, frequency, urgency, and dysuria (Shaikh et al., 2007).

An abdominal mass can suggest hydronephrosis in an infant (Elder, 2011c). Other signs and symptoms of hydronephrosis are similar to those for an infant with a UTI (Box 44-1).

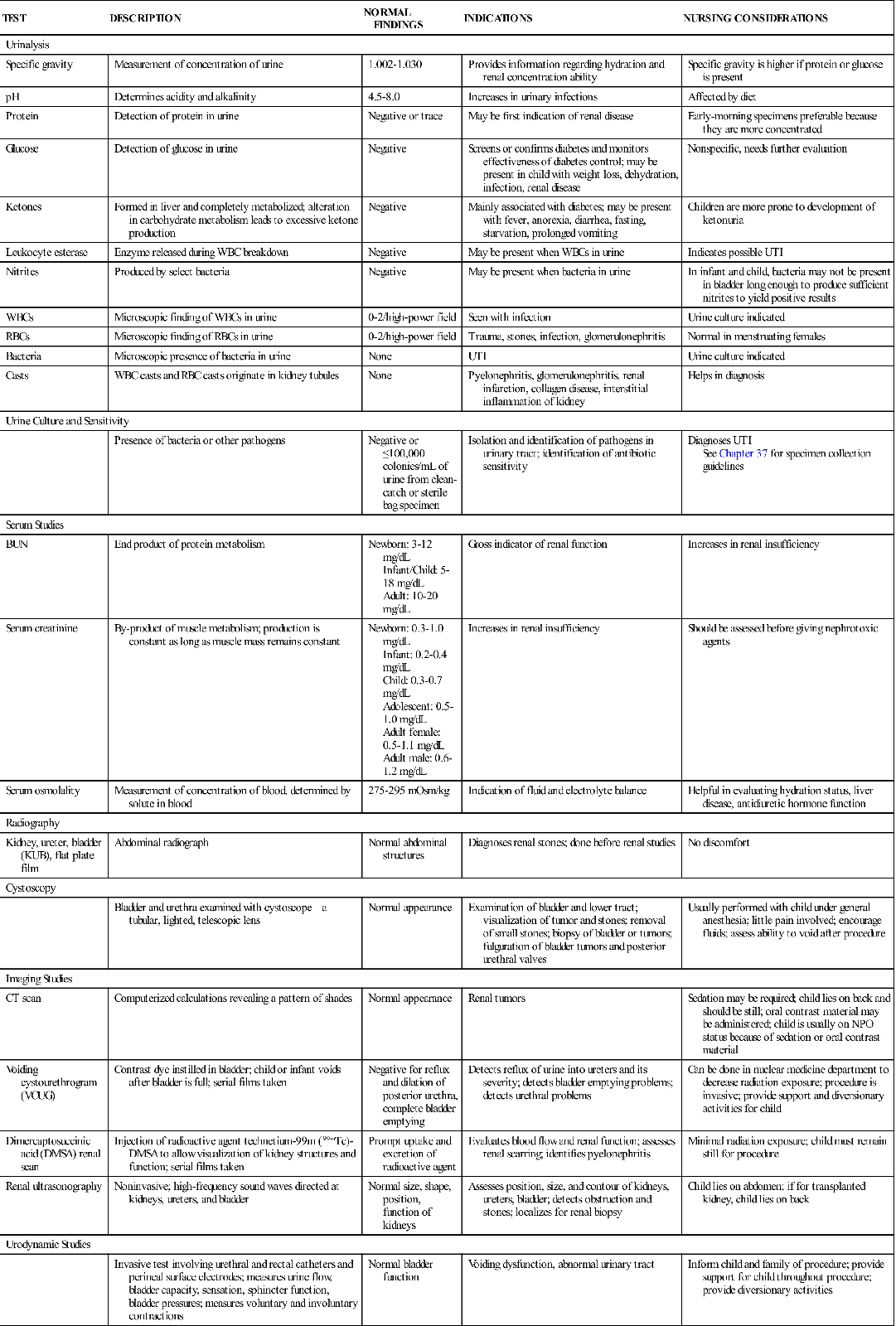

Diagnostic Evaluation

Bacteria in the urine establish a diagnosis of UTI. Symptoms of UTI in the absence of bacteriuria can be caused by perineal inflammation, vaginitis, pinworms, or chemical irritation from bubble baths.

Routine urinalysis that demonstrates hematuria, presence of white blood cells (WBCs), and positive nitrites can suggest a UTI. Urinalysis should be performed on a first morning urine specimen to be most accurate.

Urine culture is the single determining diagnostic study for a UTI. Any bacterial growth of a single-strain bacterium exceeding 100,000 colony-forming units/mL in a clean-catch urine specimen establishes a diagnosis of UTI. Obtaining a sterile urine sample is difficult in children, especially children who are not yet toilet trained. A child who can void on demand can provide a midstream clean-catch urine specimen. In infants and children who are not toilet trained, a sterile pediatric urine collection bag attached to the perineum can collect a urine specimen (see Chapter 37). Collecting urine by this method is less invasive but is clearly not as accurate for obtaining a culture as by other methods, and the urine specimen must be plated as quickly as possible. If the urine cannot be plated within 10 minutes of collection, it should be refrigerated.

When accurate determination of bacteria is the goal, more intrusive methods of bladder catheterization (see Chapter 37) or suprapubic aspiration are the collection methods of choice. If suprapubic aspiration is necessary, the area above the pubis is cleaned with an antiseptic solution, a needle attached to a syringe is inserted by the physician at a 90-degree angle into the bladder, and urine is aspirated. If catheterization or suprapubic aspiration is used to obtain a urine culture, the growth of any bacteria indicates infection.

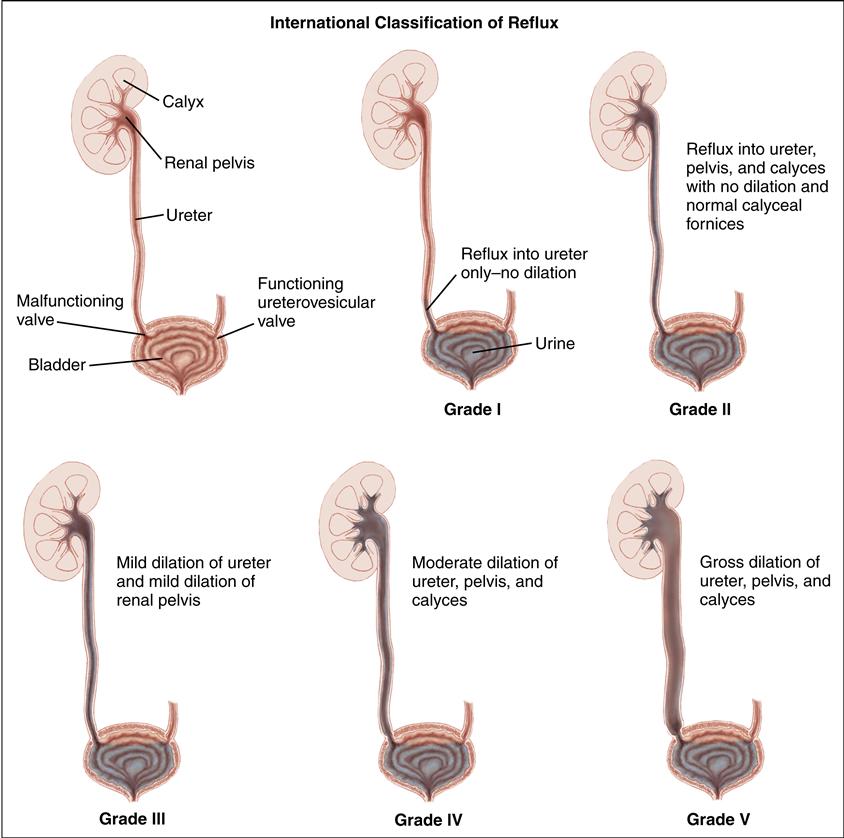

More intensive evaluation for underlying structural abnormalities is necessary for certain infants and children with UTIs. Evaluative studies include ultrasonography to detect kidney dilation resulting from obstruction and a voiding cystourethrography or radionuclide cystography to detect VUR.

Therapeutic Management

A 3- to 5-day course of oral antibiotics is the treatment of choice for an uncomplicated UTI without systemic symptoms (Elder, 2011d). The antibiotic chosen should be one to which the specific bacterium (identified by culture) is sensitive, should be easily administered, and should have minimal adverse effects. Oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, nitrofurantoin, and cephalosporins are frequently used.

Children with pyelonephritis often require initial treatment with parenteral antibiotics followed by oral antibiotic treatment. The older child who does not need hospitalization can receive daily intramuscular ceftriaxone for 1 to 2 days, followed by 10 to 14 days of oral antibiotics. Infants and children admitted to the hospital for treatment usually receive IV ampicillin and a cephalosporin or an aminoglycoside (e.g., gentamicin). Some children are treated with a cephalosporin alone. Oral antibiotics may follow this initial treatment with parenteral antibiotics.

When anatomic abnormalities are detected or UTIs recur, prophylactic antibiotic therapy might be initiated, although recent studies suggest that the risk for antibiotic resistance may be higher than the therapeutic value of prophylaxis (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2008). Prophylactic antibiotics are sometimes given to children after their initial course of treatment while they are waiting for imaging studies to confirm an underlying structural abnormality.

Because the majority of children with grades I through III VUR have a spontaneous resolution of the reflux, most physicians choose nonsurgical management of this condition (Elder, 2011e). Children are often given prophylactic antibiotics, although this has become controversial (Montini, Rigon, Zuchetta, et al., 2008), and screened for UTI every 2 to 4 months and when febrile. A voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) is performed every 12 to 18 months to monitor resolution of reflux (Elder, 2011e).

First-line surgical treatment for children with persistent grade I through III VUR is the endoscopic injection of bulking material into the submucosa of the affected ureter. The material, Deflux injectable gel, builds a protective wall inside the ureter to prevent the backflow of urine. Open surgical repair, reimplantation of the ureter into the bladder, is indicated for children who continue to have reflux and breakthrough UTIs despite antibiotic therapy, severe grade IV or V reflux, or two to three failed Deflux treatments (Elder, 2011e).

Nursing Care

The Child with a Urinary Tract Infection

Assessment

The nurse obtains a history from the child and family inquiring about age-specific signs and symptoms of UTI. Determining bowel elimination patterns is important as well, because constipation can increase the risk for UTI in certain children.

Physical assessment includes temperature, blood pressure, abdominal examination for masses, examination for costovertebral angle tenderness, and examination for genital abnormalities. It is important to obtain a urinalysis and urine culture before initiating antibiotics.

Nursing Diagnosis and Planning

The nursing diagnoses and expected outcomes that apply to the child with a UTI and the child’s family are as follows:

Expected Outcome

The child will be free of recurrent UTIs, as evidenced by the absence of voiding frequency and urgency, dysuria, and fever and the presence of a negative urine culture.

Expected Outcome

The child will maintain adequate intake of fluids and electrolytes for age, as evidenced by an output normal for age (see Chapter 40).

Expected Outcomes

The parent or child will explain the disease process, diagnostic tests, and preventive measures for UTIs. The family will follow through with appropriate follow-up care, including antibiotic administration and imaging studies, if recommended.

Interventions

Infants admitted to the hospital with fever of unknown source often are evaluated to rule out a focal infection or septicemia, as well as UTI which is one of the most frequent causes of fever in infants. The evaluation includes blood studies and cultures, lumbar puncture, and urinary catheterization or suprapubic aspiration for urine culture. The parent already is anxious about the infant, so it is imperative that the nurse inform the parent about why procedures are being done. An IV line is established at the time of the workup because parenteral antibiotics are given while waiting for laboratory results and for several days thereafter if the child has a UTI.

The nurse encourages the parents to express concerns, and provides reassurance about the infant’s condition. Every effort should be made to maintain the infant’s routine; the mother continues to breastfeed, ensuring that the IV site is protected as she holds the infant. If the breastfeeding mother is unable to remain with the infant, she will need to pump her breasts. Allowing parents to participate in the infant’s care provides them a measure of control in an uncertain situation. The infant with a documented UTI will require renal ultrasonography at the earliest convenient time.

Nursing care of the child who is not hospitalized includes ensuring administration of antibiotics, promoting comfort, maintaining good hydration, preparing the child and parent for diagnostic procedures, and monitoring for responses to treatment and possible complications.

The child and family are educated about the prevention of UTIs (see Patient-Centered Teaching: How to Manage and Prevent Urinary Tract Infections). The nurse emphasizes the importance of adhering to the treatment regimen and obtaining follow-up studies. Because repeated UTIs can contribute to renal damage, prevention is critically important. For older children, once-daily antibiotics are best administered at bedtime because of urinary stasis during the night.

Good hydration is essential for the child with a UTI, especially if the child has been febrile, nauseated, vomiting, or feeding poorly. The nurse encourages oral fluid intake, if possible. IV hydration may be required, especially for young infants. The child must be observed for signs of dehydration: poor skin turgor, dry mucous membranes, a sunken fontanel, decreased output, and decreased peripheral perfusion. Daily weights, intake and output measurements, and urine specific gravity are indicators of the child’s hydration status.

For children with VUR, the nurse explains the treatment plan, including medical or surgical management, to the parent and child in a simple, age-appropriate manner. If medical management with antibiotic therapy is elected, both parents and the child should understand that treatment may last for years and that adherence is imperative. Follow-up includes urine cultures, renal function tests (blood urea nitrogen [BUN], serum creatinine), blood pressure monitoring, and imaging studies.

Evaluation

• Is the child free of frequency, urgency, and dysuria?

• Is the urine culture negative?

• Is the child taking fluids in amounts expected for age?

• Is the child’s urine output adequate (see Chapter 40)?

• Has the child continued on the prescribed antibiotic therapy regimen?

• Has the child received follow-up diagnostic testing and antibiotic therapy?

• Can the parent or child describe symptoms of recurrence and measures to take if infection occurs?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree