The Child with a Gastrointestinal Alteration

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

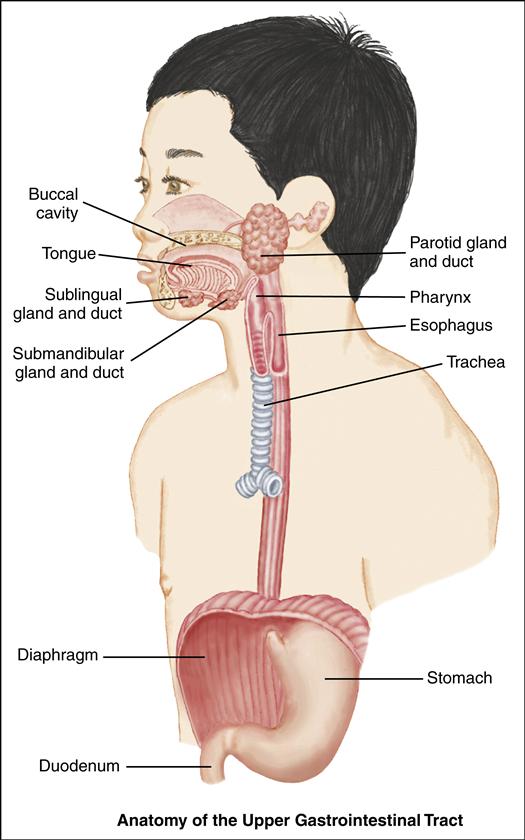

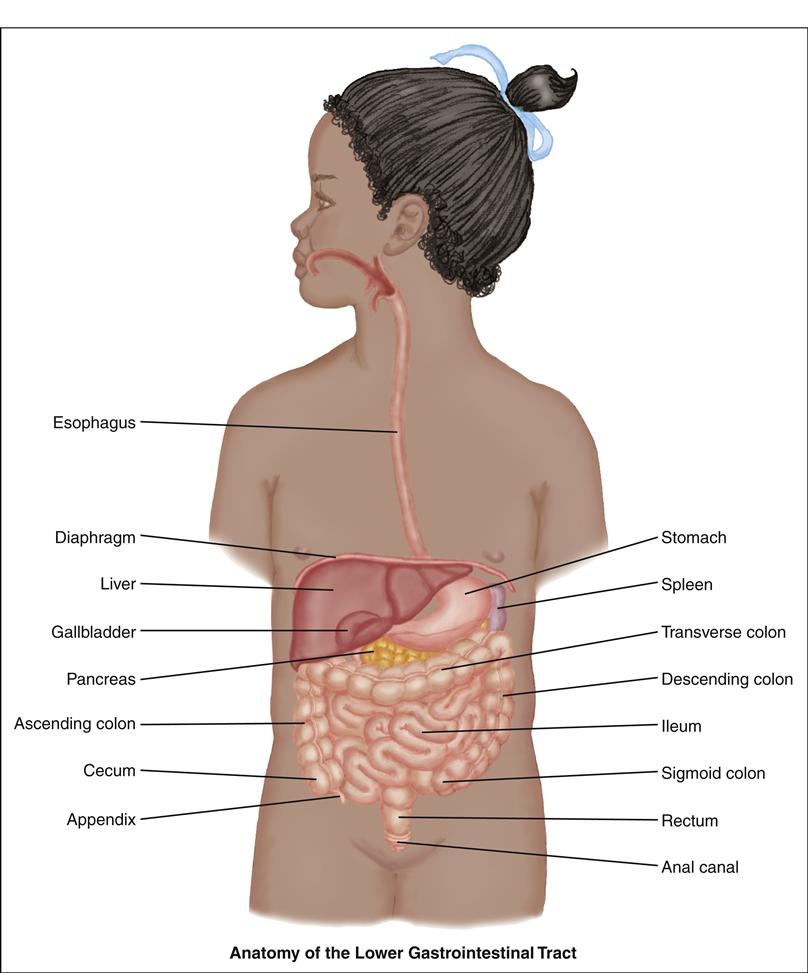

• Describe the anatomy and physiology of the gastrointestinal system in the infant and child.

• State expected nursing diagnoses for gastrointestinal alterations.

• Develop home care guidelines for the child with gastrointestinal alterations.

• Implement child and family teaching.

• Demonstrate critical thinking skills to manage a given patient care situation.

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/McKinney/mat-ch

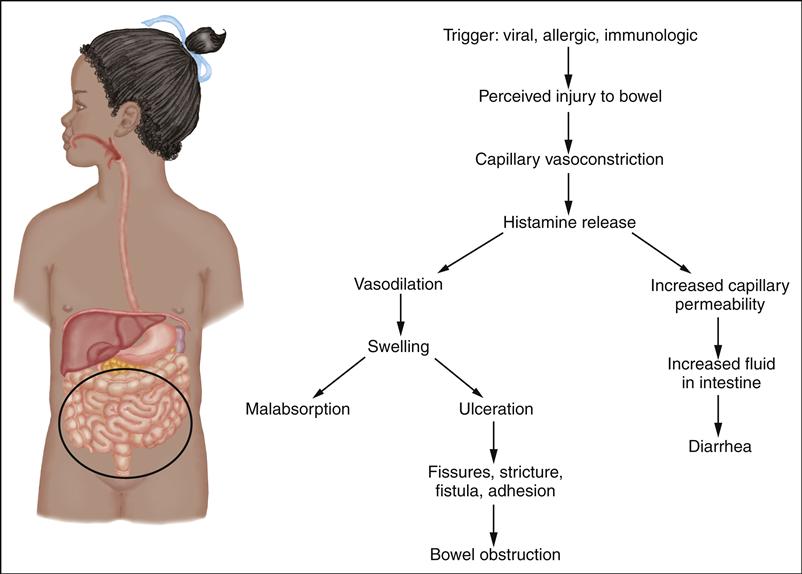

Children with GI alterations and their families have many special needs. Some GI problems begin at birth, with life-threatening consequences. Some require the parents to accept their child’s altered appearance. Other problems develop after birth and provide long-term challenges in management and treatment. Sudden, unexpected surgery may be necessary. GI alterations cause anxiety and affect nutrition, elimination, respiratory status, skin integrity, body image, family processes, growth and development, and educational needs.

Upper and lower GI conditions can be categorized as follows:

• Obstructive disorders, such as pyloric stenosis, intussusception, and Hirschsprung disease

• Malabsorption conditions, such as lactose intolerance and celiac disease

• Hepatic disorders, such as hepatitis, biliary atresia, and cirrhosis

Disorders that involve the liver and biliary tract may be the result of congenital malformations or acquired infection. Because the liver is important to metabolism, alterations in its function can affect many body systems, including the cardiovascular, integumentary, renal, neurologic, hematologic, and immunologic systems. These disorders can also have significant effects on growth and development. Nursing care may involve nutritional support, infection control, developmental stimulation, family support, and intensive physiologic care during a period of crisis.

Disorders of Prenatal Development

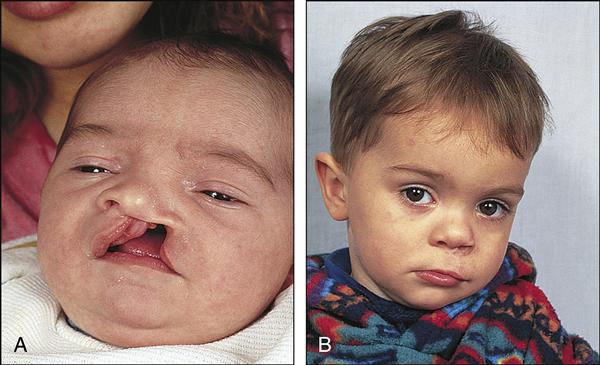

Cleft Lip and Palate

Cleft lip, cleft palate, and cleft lip and palate are separate anomalies that are closely related in etiology, pathophysiology, and nursing care. These distinct problems are all abnormal openings in the lip or palate. The defects may occur unilaterally (on either side) or bilaterally and are the most common congenital craniofacial deformity.

Incidence

The incidence ranges from 1 in 700 to 1000 births for cleft lip and palate and 1 in 2000 for cleft palate alone (Cleft Palate Foundation, 2007; March of Dimes, 2007; Zarate, Martin, Hopkin, et al., 2010). Cleft lip is seen predominantly in male infants and cleft palate in female infants. The prevalence of cleft lip and/or palate is higher in Asians and Native Americans and has a lower frequency in African-Americans. The etiology of cleft lip and palate malformations is thought to be multifactorial, including both genetic and environmental factors (Rojas-Martinez, Reutter, Chacon-Camacho, et al., 2010). While there appears

to be a genetic pattern or familial risk involved, environmental factors, such as maternal smoking, have been found to be associated with an increased risk of oral cleft defects (Lebby, Tan, & Brown, 2010). Many infants who are affected with cleft lip and palate have other associated defects.

Manifestations and Diagnostic Evaluation

Cleft lip has the following manifestations: a notched vermilion border, variably sized clefts that involve the alveolar ridge, and dental anomalies (usually deformed, supernumerary, or absent teeth). Cleft palate includes nasal distortion, midline or bilateral cleft with variable extension from the uvula and soft and hard palates, and exposed nasal cavities.

The diagnosis of cleft lip and cleft palate is based on observation at birth and complete examination in the neonatal period. Diagnosis may also be made in utero with ultrasound. Cleft lip is readily diagnosed through inspection of the lip. The first sign of cleft palate may be formula coming from the nose. A gloved finger placed in the mouth to feel the defect of the palate or visual examination with a flashlight confirms the diagnosis.

Therapeutic Management

Management is based on the severity of the defect. A number of professionals are involved in this process, including surgeons; nurses; geneticists; psychologists or psychiatrists; ear, nose, and throat specialists; audiologists; and occupational and speech therapists. Orthodontists and plastic surgeons become involved in the lengthy management. Pediatricians provide ongoing child health care.

The first intervention involves modifying feeding techniques as needed to allow adequate growth. Use of special feeding techniques, obturators, and unique nipples and feeders can usually accomplish this goal and allow early discharge home with parents (Figure 43-1). These modified techniques can decrease the energy required for the infant to take in adequate nutrition. Before surgical repair, removable orthopedic devices such as a Latham device may be used to expand and realign parts of the palate or decrease the size of a wide lip cleft.

Cleft lip repair is usually performed by age 3 to 6 months. Early repair may improve bonding and makes feeding much easier. The surgical technique involves the use of a staggered suture line to minimize scarring. Some cosmetic modifications may be needed again at age 4 to 5 years.

Cleft palate repair is individualized and based on the degree of deformity and size of the child. Closure is completed between ages 6 and 24 months. Most teams recommend repair by 1 year of age. Earlier closure facilitates speech development.

Concurrent treatment of altered dentition, recurring otitis media, speech dysfunction, emotional issues, and cosmetic concerns completes the ongoing therapy. Children with cleft palate are at high risk for developing chronic otitis media, which can cause long-term hearing loss.

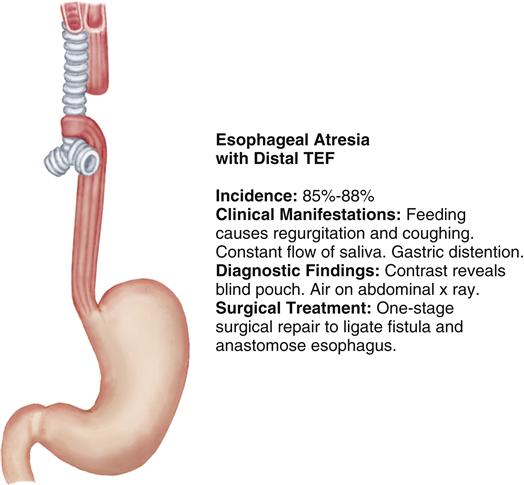

Esophageal Atresia with Tracheoesophageal Fistula

Esophageal atresia (EA) and tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) are congenital malformations in which the esophagus terminates before it reaches the stomach and/or a fistula is present that forms an unnatural connection between the esophagus and the trachea. Figure 43-2 portrays the most common type of EA with a distal TEF.

Etiology and Incidence

The cause of TEF and EA is unknown. EA with or without TEF occurs in 1.2 to 4.67 in 10,000 live births, with no difference by gender (National Birth Defects Prevention Network, 2009). Nearly half of infants born with EA have other associated anomalies of the cardiac, GI, and central nervous systems. Prematurity and low birth weight are frequent concomitant problems that significantly impact long-term prognosis.

Manifestations

Diagnostic Evaluation

A history of maternal polyhydramnios is a significant prenatal clue. If TEF is suspected prenatally, diagnosis can be made at the ideal time—in the delivery room. Atresia should be suspected if an NG tube cannot be passed 10 to 11 cm beyond the gum line. This suspicion is confirmed with an abdominal radiograph that

will identify a proximal esophagus dilated with air (atresia) or abdominal distention (fistula). The radiologist can identify the specific type of defect after instilling less than 1 mL of a water-soluble contrast medium into the NG tube and documenting its movement into the tracheal tree and the proximal pouch. This is then withdrawn from the pouch to minimize the risk of aspiration. Bronchoscopy and endoscopy are also used to identify and assess fistulas. The infant needs to have diagnostic testing for commonly associated cardiac and other congenital anomalies because these often are seen with this type of anomaly (Kahn & Orenstein, 2011a).