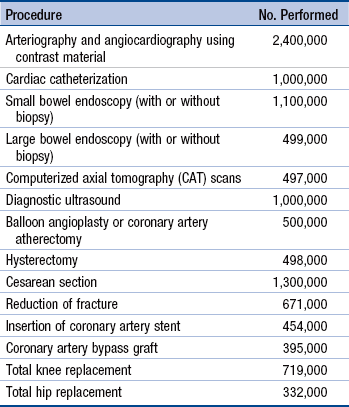

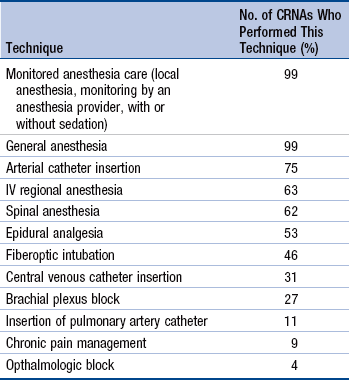

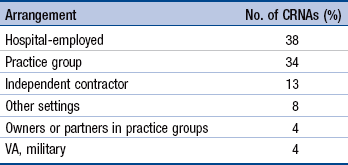

Chapter 18 Brief History of Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist Education and Practice Profile of the Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist Scope and Standards of Practice Education, Credentialing, and Certification Nurse Anesthesia Educational Funding Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist Practice Role Development and Measures of Clinical Competence The first organized program in nurse anesthesia education was offered in 1909. However, nurses have provided anesthesia since the American Civil War. There are currently 112 accredited nurse anesthesia programs, with over 2500 clinical sites in the United States and Puerto Rico. These APN educational programs are affiliated with or operated by schools or colleges of nursing, allied health, or other academic entities (Council on Accreditation of Nurse Anesthesia Educational Programs [COA], 2012a). In 1952, AANA established a mechanism for accreditation of nurse anesthesia educational programs that has been recognized by the U.S. Department of Education since 1955. Nurse anesthetists were among the first APNs to require continuing education. AANA implemented a certification program in 1945 and instituted mandatory recertification in 1978. The CRNA credential came into existence in 1956 (Bankert, 1989). CRNAs currently must be recertified every 2 years, which includes meeting practice requirements and obtaining a minimum of 40 continuing education credits (National Board for Certification and Recertification of Nurse Anesthetists [NBCRNA], 2012). In 1990, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) published research findings that demonstrated increased demand for nurse anesthetists (Mastropietro, Horton, Ouellette, et al., 2001). Successful efforts to increase the number of nurse anesthesia programs and graduates resulted in programs expanding from 89 in 1994 to 112 in 2012. In 1995, there were 1054 nurse anesthesia graduates. In 2012, 2525 students will complete nurse anesthesia educational programs. Some 45,000 CRNAs currently practice in the United States. The economic downturn of the last several years has caused some practitioners to delay retirement. However, AANA member survey data have indicated that 22% of AANA members plan to retire between 2014 and 2018, and another 20% expect to retire between 2019 and 2022 (AANA 2012a; COA, 2012a). There will continue to be a robust demand for CRNAs in the United States. Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicated that 51.4 million surgical and diagnostic procedures were performed in 2010 (CDC, 2010). The number of selected procedures performed is shown in Table 18-1. CRNAs provide anesthesia for approximately 32 million surgical and diagnostic procedures in the United States each year (AANA, 2012b). The impact of the aging population, coupled with implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA; HHS, 2011), if operationalized as planned, will result in more surgical and diagnostic procedures being performed. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) report on the Future of Nursing (2010) noted that “transforming the health care system to meet the demand for safe, quality and affordable care will require a fundamental rethinking of the roles of many health care professionals, including nurses. The 2010 Affordable Care Act represents the broadest health care overhaul since the 1965 creation of the Medicare and Medicaid programs, but nurses are unable to fully participate in the resulting evolution of the U.S. health care system” (p. 21). The IOM report expressed concern that physicians challenge expanding scopes of practice for nurses and that “given the great need for more affordable health care, nurses should be playing a larger role in the health care system, both in delivering care and decision making about care” (p. 26). The IOM report concluded that “now is the time to eliminate outdated regulations and organizational and cultural barriers that limit the ability of nurses to practice to the full extent of their education, training and competence. … Scope of practice regulations in all states should reflect the full of extent of … each profession’s education and training” (IOM, 2010, p. 96). CRNAs are the predominant anesthesia providers in rural America, enabling health care facilities in these medically underserved areas to provide patient access to surgical, obstetric, pain management, and trauma stabilization services. In some states, these APNs are the sole anesthesia providers in almost 100% of rural hospitals (AANA, 2012a). In addition to providing anesthesia services in rural America, CRNAs have long contributed to the care of medically underserved citizens. Reports in peer-reviewed journals have continued to document the safety and cost-effectiveness of care provided by CRNAs (Dulisse & Cromwell, 2010; Hogan, Seifert, Moore, et al., 2010; Pine, Holt, & Lou, 2003; Simonson, Ahern, & Hendryx, 2007). Findings reported in these papers demonstrate that there is no difference in the quality of care provided by CRNAs and their physician counterparts. Legislation passed by Congress in 1986 provided direct billing for CRNAs under Medicare Part B. In 2001, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) allowed states to opt out of the reimbursement requirement that a surgeon or anesthesiologist oversee anesthesia services provided by CRNAs. Dulisse and Cromwell (2010) have noted that by 2005, 14 states exercised this option. To date, 17 states have opted out of Medicare Part A CRNA supervision requirements (AANA, 2012c; Table 18-2). An analysis of Medicare data for 1999 to 2005 found no evidence that opting out of the oversight requirement resulted in increased inpatient morbidity or mortality (Dulisse & Cromwell, 2010). States That Have Opted Out of CRNA Medicare Part A Supervision Adapted from American Association of Nurse Anesthetists. (AANA). (2012c). Federal supervision rule/opt-out information. (http://www.aana.com/advocacy/stategovernmentaffairs/Pages/Federal-Supervision-Rule-Opt-Out-Information.aspx). A recent cost-effectiveness analysis of anesthesia providers found that CRNAs are less costly to train than anesthesiologists and can perform the same set of anesthesia services, including relatively rare and difficult procedures such as open heart surgery, organ transplantation, and pediatric procedures. In concert with the IOM report, the investigators noted that “as the demand for health care continues to grow, increasing the number of CRNAs and permitting them to practice in the most efficient delivery models, will be a key to containing costs while maintaining quality of care” (Hogan et al., 2010, p. 159). Nurse anesthetists have been the main providers of anesthesia care to U.S. military men and women on the front lines of combat since World War I. Documentation of nurses providing anesthesia to wounded soldiers dates back to the American Civil War. Currently, 3.5% of U.S. nurse anesthetists serve in the military or Veterans Administration (VA) facilities (AANA, 2012d). Regarding malpractice coverage, insurance rates for self-employed CRNAs have declined significantly since the 1980s (AANA, 2010a). In 2009, the average CRNA malpractice premium was 33% lower than in 1988, or 62% lower when adjusted for inflation. This decline in malpractice premium rate reflects the safe care provided by nurse anesthetists. The rate drop is impressive given inflation, our litigious society, and generally higher jury awards (AANA, 2010a). Men have historically been more represented in nurse anesthesia compared with nursing as a whole. Approximately 45% of the nation’s 45,000 nurse anesthetists and student nurse anesthetists are men, compared with about 8% in the nursing profession. When all employed CRNAs are examined, 45% are men and 55% are women. The gender balance shifts significantly with part-time employees; 77% of part-time CRNAs are women and 23% are men. Currently, more than 90% of U.S. nurse anesthetists are members of the AANA (AANA, 2012a). CRNAs provide anesthesia services in collaboration with surgeons, anesthesiologists, dentists, podiatrists, and other qualified health care professionals. When anesthesia is administered by a nurse anesthetist, it is recognized as the practice of nursing; when administered by an anesthesiologist, it is recognized as the practice of medicine (AANA, 2012e). Regardless of their educational backgrounds, all anesthesia providers adhere to the same standards of care. Nurse anesthetists are APNs who practice in every setting in which anesthesia is delivered—traditional hospital surgical suites and obstetric delivery rooms, critical access hospitals, ambulatory surgical centers, the offices of dentists, podiatrists, ophthalmologists, plastic surgeons, and pain management specialists, endoscopy centers, and U.S. military, public health services, and Department of Veterans Affairs health care facilities. A CRNA is a registered nurse who is educationally prepared at the graduate level and certified as competent to engage in practice as a nurse anesthetist, rendering patients insensible to pain with anesthetic agents and related drugs and procedures. Anesthesia services are delivered by anesthesia providers on request, assignment, or referral by the operating physician or other health care provider authorized by law, usually to facilitate diagnostic, therapeutic, or surgical procedures. In addition to general or regional anesthesia techniques, as well as monitored anesthesia care, a referral or request for consultation or assistance may be initiated for the provision of obstetric anesthesia services, ventilator management, or treatment of acute or chronic pain through the performance of selected diagnostic or therapeutic blocks, or other forms of pain management. Education, practice, and research within the specialty of nurse anesthesia promote competent anesthesia care across the life span at all acuity levels. CRNAs practice according to their expertise, state statutes and regulations, and institutional policy (AANA, 2010b). CRNAs work collaboratively with all members of the perioperative team, including nurses, technicians, surgeons, and anesthesiologists. CRNAs are responsible and accountable for their individual professional practices and are capable of exercising independent judgment within the scope of their education (credentials), demonstrated competence (privileges), and licensure. CRNAs are recognized in all 50 states by state regulatory bodies, primarily boards of registered nursing. Nurse anesthesia is a recognized nursing specialty role and is not a medically delegated act (AANA, 2012e). Compensation, along with role-related autonomy and responsibility, continue to attract qualified applicants to this advanced practice nursing specialty. The most recent data for full-time CRNAs, excluding those who are self-employed, show a mean salary of $165,571. CRNAs employed by hospitals had higher median annual compensation rates ($171,000) than group employees ($153,000) or military or VA-employed CRNAs ($160,000; AANA, 2012a). The CRNA practice profile is influenced by the work of the AANA Practice Committee and AANA Professional Practice Department. The Professional Practice Department participates in safety and quality issues, including reduction of needlestick injuries and safe injection practices. AANA is represented at the National Patient Safety Foundation and is involved with the Ambulatory Surgery and Office Surgery Initiative. AANA is a major stakeholder and participant in the National Quality Forum, addressing patient safety issues (AANA, 2012f). The Scope and Standards of Nurse Anesthesia Practice, as set forth by the AANA, is comprehensive and includes all aspects of anesthesia care (AANA, 2010b). Regardless of the setting in which CRNAs practice, their role includes meeting the individual anesthesia care needs of patients in the perioperative period, including the following (AANA, 2010b): • Performing and documenting a preanesthetic assessment and evaluation of the patient, including requesting consultations and diagnostic studies; selecting, obtaining, ordering and administering preanesthetic medications and fluids; and obtaining informed consent for anesthesia • Developing and implementing an anesthetic plan • Initiating the anesthetic technique, which may include general, regional, and local anesthesia and sedation • Selecting, applying, and inserting appropriate noninvasive and invasive monitoring modalities for continuous evaluation of the patient’s physical status • Selecting, obtaining, and administering the anesthetic, adjuvant and accessory drugs, and fluids necessary to manage the anesthetic • Managing a patient’s airway and pulmonary status using current practice modalities • Facilitating emergence and recovery from anesthesia by selecting, obtaining, ordering, and administering medications, fluids, and ventilator support • Discharging the patient from a postanesthesia care area and providing anesthesia follow-up evaluation and care • Implementing acute and chronic pain management modalities • Responding to emergency situations by providing airway management, administering of emergency fluids and drugs, and using basic or advanced cardiac life support techniques • Administration and management—scheduling, material and supply management, development of policies and procedures, fiscal management, performance evaluations, preventive maintenance, billing, data management, and supervision of staff, students, or ancillary personnel • Quality assessment—data collection, reporting mechanisms, trending, compliance, committee meetings, departmental review, problem-focused studies, problem solving, intervention, document and process oversight • Education—clinical and didactic teaching, basic cardiac life support and advanced cardiac life support instruction, in-service commitment, emergency medical technician training, supervision of residents, and continuing education • Research—conducting and participating in departmental, hospital-wide, and university-sponsored research projects • Committee appointments—assignment to committees, committee responsibilities, and coordination of committee activities • Interdepartmental liaison—interface with other departments such as nursing, surgery, obstetrics, postanesthesia care units (PACUs), outpatient surgery, admissions, administration, laboratory, and pharmacy • Clinical and administrative oversight of other departments—for example, respiratory therapy, PACU, operating room, surgical intensive care unit (SICU), and pain clinics. (AANA, 2010b) The Scope and Standards of Nurse Anesthesia Practice (AANA, 2010b) addresses the responsibilities associated with anesthesia practice that are performed in collaboration with other qualified health care providers. Collaboration “is a process which involves two or more parties working together, each contributing his or her respective area of expertise. CRNAs are responsible for the quality of services they render” (AANA, 2010b, p. 1). Anesthesia care is provided by CRNAs in four general categories: (1) preanesthetic evaluation and preparation; (2) anesthesia induction, maintenance, and emergence; (3) postanesthesia care; and (4) perianesthetic and clinical support functions. Parallels between nursing and nurse anesthesia are apparent. CRNAs perform preanesthetic assessment, plan appropriate anesthetic interventions, implement planned anesthetic care, and evaluate patients postoperatively to determine the efficacy of their interventions. CRNAs working independently routinely perform all these aspects of clinical practice. When CRNAs and anesthesiologists work together, a variety of factors, such as billing arrangements and local anesthesia practice patterns, determine to what extent each practitioner is involved in specific anesthesia care areas (AANA, 2010b). Preoperative evaluation has become more complex with the increasing acuity of surgical patients. Thorough preanesthetic assessments, combined with specialty consultation as needed, are essential activities at which nurse anesthetists must be proficient (AANA, 2010b). The scope of practice for CRNAs varies depending on institutional credentialing. Although most CRNAs provide general anesthesia and monitored anesthesia care, survey data show a noticeable decrease in the frequency with which regional anesthesia is performed relative to general anesthesia. Placement of invasive monitoring lines and pain management techniques are less commonly performed by nurse anesthetists. Practice restrictions may not always be imposed via the credentialing process; some providers choose not to perform certain types of procedures. See Table 18-3 for the breakdown of techniques performed by CRNAs who completed AANA member surveys (N = 5377) in 2011. Techniques Performed by CRNA Survey Respondents Adapted from American Association of Nurse Anesthetists. (AANA). (2012a). AANA member survey data. (http://www.aana.com/myaana/AANABusiness/aanasurveys/Documents/aana-member-survey-data-nov2011.pdf). To become a CRNA, the following requirements must be met (COA, 2012b): • Complete a Bachelor’s of Science in Nursing degree or other appropriate baccalaureate degree. • Hold current licensure as a registered nurse (RN). • Complete at least 1 year as an RN in an acute care setting. • Graduate from a nurse anesthesia program accredited by the COA or its predecessor. • Successfully complete the national certification examination offered by the National Board of Certification and Recertification for Nurse Anesthetists for CRNAs or its predecessor. • Comply with the criteria for biennial recertification as defined by the National Board of Certification and Recertification for Nurse Anesthetists. These criteria include evidence of the following: (1) current licensure as a registered nurse; (2) active practice as a CRNA; (3) appropriate continuing education; and (4) verification of the absence of mental, physical, and other problems that could interfere with the practice of anesthesia. In the mid-1970s, over 170 nurse anesthesia educational programs existed. A rapid decline in the numbers of nurse anesthesia programs occurred in the 1980s, a change that was of great concern to the specialty. The closures were attributed variously to physician pressure, declining support, the inability of hospitals to continue support of small programs, and lack of a geographically accessible universities with which a nurse anesthesia program could affiliate (Faut Callahan, 1991). Those who argued that nurse anesthesia programs closed solely because of the graduate degree mandate offered little evidence to support that claim. One can surmise that if the requirement for graduate education was the only reason for program closures, those programs would have remained open until 1998, when the master’s degree was required. Despite the decline in the overall numbers of nurse anesthesia programs, many of which were certificate programs with enrollments of less than five students, the level of educational programs has changed dramatically. After an initial decline in graduates, the newer graduate programs increased their admissions. To accomplish this, programs had to increase the numbers of clinical training sites. This resulted in a strengthened educational system, deeply entrenched in an academic model. Colleges of nursing now house 57% of nurse anesthesia educational programs in the United States, reflecting increasing collaboration between all APN groups on education, legislative, and policy matters (COA, 2012a). Because AANA founder Agatha Hodgins unsuccessfully sought a place for CRNAs within the American Nurses Association, a separate professional organization (AANA) was formed (Bankert, 1989; Thatcher, 1953). However, rapprochement between nursing and nurse anesthesia has resulted in effective collaboration (Mungia-Biddle, Maree, Klein, et al., 1990). Coalitions of APNs have effectively worked together on the state and federal levels on health reform and other issues for many years. Nurse anesthesia educational curricula include time requirements for didactic and clinical activities that reflect minimum standards for entry into practice. Academic content areas are crucial to the preparation of practitioners for beginning-level competence in a highly demanding, rapidly changing specialty. Various colleges and schools that administratively house nurse anesthesia programs may have additional academic requirements. Nurse anesthesia programs in colleges of nursing include core graduate-level courses taken by all graduate-level nursing students. These courses include graduate-level nursing theory, nursing research, advanced physical assessment, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. The mandated content areas for nurse anesthesia programs are listed by the COA by required clock hours (COA, 2012b): • Pharmacology of anesthetic agents and adjuvant drugs, including concepts in chemistry and biochemistry: 105 hours • Anatomy, physiology, and pathophysiology: 135 hours • Professional aspects of nurse anesthesia practice: 45 hours • Basic and advanced principles of anesthesia practice, including physics, equipment, technology, and pain management: 105 hours The clinical component requires that students administer a minimum of 550 anesthetics. An external agency, the National Board of Certification and Recertification for Nurse Anesthetists, requires that students complete given numbers of surgical procedures and anesthetic techniques. For example, all graduates must have administered at least 25 general anesthetics using a mask airway, versus a laryngeal mask or endotracheal intubation, and care for patients across the lifespan. Similarly, required numbers of specific clinical experiences, such as endotracheal intubations or thoracic surgical cases, must be met for nurse anesthesia graduates to be eligible to take the national certification examination. Most programs exceed these minimum requirements. The average student nurse anesthetist logs at least 1694 clinical hours and administers more than 790 anesthetics. In addition, many programs require study in methods of scientific inquiry and statistics, as well active participation in student-generated and faculty-sponsored research (COA, 2012a). The COA accredits nurse anesthesia educational programs. Council members include nurse anesthesia educators and practitioners, nurse anesthesia students, health care administrators, university representatives, and the public. The COA conducts mandatory, on-site program reviews, with a maximum accreditation period of 10 years. Nurse anesthesia educators and the COA have found that retaining a prescriptive curriculum in terms of hours and types of clinical experiences has helped the survival of educational programs. That is, when documented deviations from established standards for nurse anesthesia educational programs occur, such as physicians restricting clinical access, program administrators can cite COA standards mandating these experiences (COA, 2012a). Despite growth in the national debt, Title VIII funding has continued. The Nurse Anesthetist Traineeship (NAT) program provides support for student registered nurse anesthetists who are enrolled full-time in a master’s or doctoral nurse anesthesia program. Traineeship funds may be used to offset costs for tuition, books, fees, and reasonable living expenses for students during the period for which the traineeship is provided. In 2012, the NAT program changed to include first-year nurse anesthesia students, who previously were eligible for traineeship funding under the Advanced Education Nurse Training program. The total NAT funding available for 100 estimated applicants in 2012 is $2,250,000 (Health Resources and Services Administration [HRSA], 2012). Historically, nurse anesthesia curricular requirements have overloaded the typical master’s curriculum. The current required minimum length of nurse anesthesia programs is now 24 months, but that will change by 2025 because all nurse anesthesia programs will be required to be a minimum of 36 months in length, which is required by COA’s additional criteria for practice-oriented doctoral degrees (COA, 2012b). The vision of nursing leader Dr. Luther Christman for nurses to be prepared with advanced degrees, both in their discipline and in a basic science, reflects the trend to move to doctoral entry in anesthesia and other advanced practice specialties. At this writing, nurse anesthesia is the only APN specialty to have a timeline requiring the transition of all programs to the practice doctorate level. Although nurse anesthesia faculty previously described limitations such as time and finances that would interfere with their pursuit of a doctoral degree (Jordan & Shott, 1998), the number of CRNAs prepared at the doctoral level has more than doubled in the recent past, from 1.2% to 3% (AANA, 2012a). Many CRNAs are currently pursuing practice or research doctorates, which bodes well for the future of the specialty and its transition to doctoral education. Practice doctorates offered in nurse anesthesia programs include the Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) and the Doctor of Nurse Anesthesia Practice (DNAP). The DNP is typically offered for programs housed in schools of nursing and the DNAP may be the exit degree for nurse anesthesia programs located in schools of allied health or other academic units. Regardless of the degree offered, nurse anesthesia practice doctorates must comport with the additional criteria for practice-oriented doctoral degrees that are included in the COA Standards for Accreditation of Nurse Anesthesia Educational Programs. These criteria include a minimum program length of 36 months, demonstration of adequate numbers of faculty prepared at the doctoral level, and completion of a final scholarly work (COA, 2012b). Nurse anesthesia was the first nursing specialty to have mandatory certification. This process began in 1945, when the first certification examination in nurse anesthesia was given (Bankert, 1989). The NBCRNA is separately incorporated from AANA. NBCRNA notes that “certification is a process by which a professional agency or association certified that an individual licensed to practice a profession has met certain standards specified by that profession for specialty practice. The purpose of certification is to assure the public that an individual has mastered a body of knowledge and acquired skills in a particular specialty” (www.NBCRNA.com). NBCRNA uses psychometricians, an academy of test item writers, and computer adaptive testing to assess beginning-level competence in nurse anesthesia practice. A professional practice analysis is performed at regular intervals by the NBCRNA to determine which entry-level competencies are necessary for a new nurse anesthesia graduate. The AANA Continuing Education Department is responsible for the review and approval of continuing education programs sponsored by the AANA and other organizations, maintenance of attendance records of CE activities, and preparation of CE transcripts and certificates of attendance for AANA-sponsored programs (AANA, 2012g). In 2012, the NBCRNA announced a Continued Professional Certification (CPC) program that will become operational in 2016. Under this system, the certification period will be 4 years. The continuing education requirements will be 15 assessed continuing education units per year. In addition, 10 professional activity units (developmental activities that do not require assessment) will be required each year. The CPC program will require four self-study modules every 4 years on subjects addressing core competencies in anesthesia, such as airway management techniques, applied clinical pharmacology, physiology, pathophysiology, and anesthesia technology. Continued education credits will be awarded when these modules are completed. A competency examination will be phased into the program over the next 20 years. Required at 8-year intervals, the first examination will be available in 2020. The examination will be used for diagnostic and developmental purposes. In 2032, all nurse anesthetists will be required to meet a passing standard on the recertification examination at 8 year intervals. Four attempts to pass the test within a 4-year recertification cycle will be allowed (NBCRNA, 2012). Competence can be partially ensured through institutional credentialing processes. A hospital or other facility may delineate procedures that the CRNA is authorized to perform by the authority of its governing board. Guidelines for granting CRNAs clinical privileges are found in an AANA Sample Application for Clinical Privileges (AANA, 2010c). Recommended clinical privileges for CRNAs are in the areas of preanesthetic preparation and evaluation, anesthesia induction, maintenance, and emergence, post-anesthetic care, and perianesthetic and clinical support functions (AANA, 2010c). COA has required the master’s degree as the exit degree for nurse anesthesia programs since 1998. The COA will not approve any new master’s degree programs for accreditation beyond 2015. Students accepted into an accredited program on January 1, 2022 and thereafter will need to complete the program with a doctoral degree. COA standards require that program administrators (program administrator and assistant administrator) will be required to have a doctoral degree by 2018; clinical site coordinators will need to have a master’s degree by 2014 (COA, 2012b). Data that comprise CRNA practice profiles are derived from annual practice surveys completed by CRNAs when they pay their AANA dues. The response rate to these surveys has been as high as 72%, providing a reasonable degree of generalizability. AANA membership has grown by 20,000 from 1996 to 2012, from 25,000 to 45,000 CRNAs. This growth rate bodes well for the future of nurse anesthesia, along with the continued availability of high-quality, cost-effective anesthesia services, especially to citizens in rural and medically underserved areas. This growth reflects the work of the National Commission on Nurse Anesthesia Education (Maree, 1991), which provided the profession with workforce data projections and related strategies to ensure that the market demand for nurse anesthetists will be met. The growth in nurse anesthesia programs and graduates over the last 20 years can be attributed to the advocacy of AANA, through the National Commission on Nurse Anesthesia Education, for the development of new educational programs to meet increasing needs for anesthesia services (Mastropietro, et al., 2001). The average age of CRNAs reported in the AANA 2011 membership survey was 49.8 years, similar to the average age for registered nurses in the United States. Regarding the duration of time spent in the specialty, 37% of CRNAs who responded to this survey had been in practice longer than 20 years and 23% were in practice for 11 to 20 years. A number of CRNA retirements can be expected between 2014 and 2018, because 22% of survey respondents indicated that they planned to retire during this time frame; another 20% of AANA members believe that they will retire between 2019 and 2022. Given the aging population and the potential impact of the PPACA, with over 30 million additional people covered, it is essential that nurse anesthesia educational programs continue to produce adequate numbers of graduates to meet workforce needs (AANA, 2012a). A CRNA workforce study conducted 7 years ago showed a CRNA vacancy rate of 12% (Merwin, Stern, & Jordan, 2006). However, the current vacancy rate is much lower. For various reasons, many people in the workforce remain employed beyond the traditional retirement age. CRNA faculty surveyed in 2007 indicated that their timeline to expected retirement was similar to that of clinicians (Merwin, Stern, & Jordan, 2008). Between 2014 and 2022, 42% of CRNA survey respondents plan to retire and, after 2022, 51% plan to retire (AANA, 2012a). The current and future needs of nurse anesthesia programs mandate a faculty cadre to teach the rigorous didactic and clinical portions of nurse anesthesia programs and to manage the transition to the practice doctorate. Faculty survey respondents noted that the salary differential between academic and clinical settings was the biggest barrier to the recruitment of academic faculty. Projected retirements and increases in health care coverage demand a health care workforce sufficient to deliver patient access to high-quality health care. The PPACA included a 4-year pilot project for Graduate Nursing Education (GNE) intended to support the clinical practice education of APRNs for the growing Medicare patient population. GNE seeks to ensure that the education of advanced practice nurses has funding opportunities similar to those provided for physicians under Graduate Medical Education (GME; CMS, 2012). AANA membership survey data indicate that 81% of respondents work full time; 15% work part time, 3% are retired, and 1% are unemployed (AANA, 2012a). Nurse anesthetists have provided most anesthesia services in rural areas since the inception of the specialty. However, most CRNAs reside in urban areas; 81.4% live in urban areas, as defined by Urban Influence Codes 1 and 2, and 18.6% of nurse anesthetists are nonmetropolitan residents, with addresses in Urban Influence Codes 3 to 12. Most CRNAs provide anesthesia services in hospitals with more than 200 beds (AANA, 2012a). At one time, CRNAs were primarily hospital-employed. However, employment arrangements for CRNAs have changed over time (Table 18-4; AANA, 2012a). Employment Arrangements of CRNAs Adapted from American Association of Nurse Anesthetists. (AANA). (2012a). AANA member survey data. (http://www.aana.com/myaana/AANABusiness/aanasurveys/Documents/aana-member-survey-data-nov2011.pdf).

The Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist

Brief History of Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist Education and Practice

![]() TABLE 18-2

TABLE 18-2

State

When Enacted

Iowa

December 2001

Nebraska

February 2002

Idaho

March 2002

Minnesota

April 2002

New Hampshire

June 2002

New Mexico

November 2002

Kansas

March 2003

North Dakota

October 2003

Washington

October 2003

Alaska

October 2003

Oregon

December 2003

Montana

June 2005

South Dakota

March 2005

Wisconsin

July 2005

California

July 2009

Colorado

September 2010 (for critical access hospitals and specified rural hospitals)

Kentucky

April 2012

Role Differentiation Between Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists and Anesthesiologists

Profile of the Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist

Scope and Standards of Practice

![]() TABLE 18-3

TABLE 18-3

Education, Credentialing, and Certification

Programs of Study

Nurse Anesthesia Educational Funding

Practice Doctorate

Certification

Institutional Credentialing

Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist Practice

Workforce Issues

![]() TABLE 18-4

TABLE 18-4

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access