CHAPTER 8 The aged care sector: residential and community care

When you finish this chapter you should be able to:

Introduction

Like other aspects of health care, aged care has become an issue of intense political debate. Governments want to minimise the costs of providing care for the elderly but no politician wants to be seen as denying care to older members of the community, depicted as vulnerable people who have worked hard all their lives. One response to these dilemmas has been a shift from welfare-based provision of services to a market-driven approach, where low-cost services are targeted at those in need while richer older people are expected to contribute to the costs of care. There have been frequent changes to the regulations that determine who is eligible for low-cost care, and a new industry of financial planning has evolved to help older Australians arrange their finances to qualify for subsidised care. As a result of this complexity, interest groups have become increasingly vocal in their demands for aged care services to be provided in a manner that is equitable, easy to understand and predictable.

Population trends

The number and proportion of older people in Australia have been increasing for several years. There was a big increase in the number of births between 1946 and 1961, with over 4 million Australians born as people recovered from the hardship of World War Two (Culture and Recreation Portal 2007). These baby boomers are now reaching old age. Large numbers of immigrants arrived in the post-war period and these people, too, are growing older. We are also living longer. Life expectancy increased by over 20 years in the period 1901–2001 (see Table 8.1) and there has also been a decline in the birth rate, magnifying the proportion of older people. There is concern about whether there will be enough ‘young’ people in future to pay taxes and provide the care needed by the growing number of ‘old’ people. In response, the Australian Government introduced substantial financial incentives for new mothers in 2001 and there has been an increase in births since 2002 (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS] 2007b).

Table 8.1 Life expectancy in years for different birth cohorts

| Year of birth | Males | Females |

|---|---|---|

| 1901–1910 | 55.2 | 58.8 |

| 1999–2001 | 77.0 | 82.4 |

| 2050–2051 (estimated) | 84.2 | 87.7 |

Source: Hogan 2004

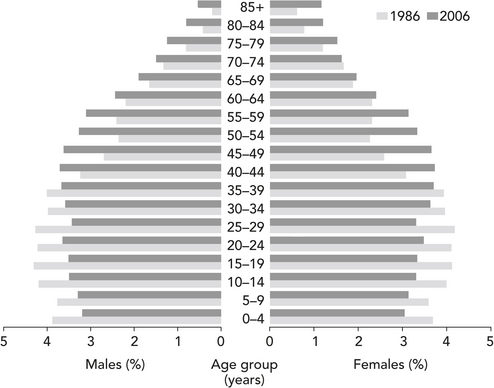

A closer look at the statistics reveals the extent of these changes. At the 2006 Census, 24.3% of the population was aged 55 or over, up from 22% in 2001 (ABS 2007b). Figure 8.1 shows that the increase in the number of people aged 85 and over is particularly striking (ABS 2006f) and this is the age group that is most likely to require health care (McCallum 2000). Even so, a decline in health is not inevitable as people get older. The challenge for health care workers is to help people maintain their wellbeing as they age so as to prevent or delay the onset of illness.

Hospital care

Older patients are admitted to both public and private hospitals. As discussed in Chapter 5, many older Australians maintain their private health insurance cover despite its cost, believing that it gives them choice and greater access to care. Meanwhile, insurance companies have to meet the escalating costs associated with older patients. This is a consequence of the market model of private health insurance in Australia. In turn, the fact of having private health cover may increase demand for care. Walker et al (2006) found that the wealthiest quintile of people aged over 60 years in NSW was more likely to be hospitalised than others of the same age, despite having generally better health. For example, they were admitted to private hospitals for procedures such as screening tests or chemotherapy because they had health insurance. Patients without insurance underwent these procedures as outpatients in public hospitals. This suggests that a review of policies governing hospital admission for insured patients may help to contain the costs of elder health care.

Aged care in the community

In the 1950s and 1960s, community groups and municipalities started to develop services for elderly people living at home and their carers. These services were fragmented, not always needs based and recipients had little voice in how they were run (Walker-Birckhead 1985). At the same time, the Federal government was spending heavily on nursing homes for the elderly, informed by a perspective that saw ageing as a medical problem (Healy 1990). The establishment of the Home and Community Care (HACC) program by the Federal government in 1985 signalled a major policy shift to provide services based on needs rather than age alone (Healy 1990). HACC is jointly funded by Federal, state and territory governments and aims to provide integrated services to the frail elderly and people with disabilities living at home (Palmer & Short 1994). Three smaller programs, Community Aged Care Packages (CACP), Extended Aged Care at Home (EACH) and EACH Dementia provide care at home for people with complex needs who would otherwise be in residential care (AIHW 2007c).

Traditionally, families provided care for their older members with little support from outside agencies. This informal care continues to be of major importance in helping frail older people stay at home. The burden of care does not fall evenly across the community. Of the 500 000 primary carers in Australia 70% are women and 29% are over 60 years old; 23% care for a parent; 43% of all carers, but 69% of those over 60, care for a spouse/partner. Over half of all carers spend 20 hours a week or more providing unpaid care. Many experience fatigue and reduced wellbeing as a result. The Commonwealth government supports some carers financially through carers’ payments that supplement or replace income from paid work (Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing 2004). Even so, one estimate valued the work of unpaid carers at $19.3 billion, or almost double the amount paid by governments to welfare services (AIHW 2004b).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Pause for reflection

Pause for reflection Pause for reflection

Pause for reflection