Chapter 23

The Acutely Ill or Injured Patient1

There is no thing more precious here than tyme.

Saint Bernard (1090–1153)

The objective of this chapter is to provide a practical approach to acutely ill and injured patients. The emphasis is on a prioritized assessment and diagnostic considerations, not on therapy. The chapter is for those who care for patients outside of traditional medical settings and those who provide care in traditional health care environments such as clinics, doctors’s offices, and hospitals.

In the assessment of acutely ill and injured patients, time can be a critical factor. Developing an organized, structured approach to rapidly assess the critically ill and injured patient is important to beginning the correct lifesaving therapies and identifying the proper resources and environment to take ideal care of the patient.

In contrast to the assessment of stable patients, the evaluation of acutely ill patients involves the rapid, systematic identification of pathophysiologic abnormalities that may require the initiation of lifesaving therapies while the final diagnosis is under investigation. Many causes of acute illness may have overlapping signs and symptoms that require investigation to discover the root cause, but therapy must begin to prevent further harm or death to the patient.

In the evaluation of acutely ill patients, it is always helpful to ask yourself, “What is the most serious threat to life, and have I begun to stabilize it as much as possible?”, followed by asking, “What is the most likely cause and what have I ruled out so far?”

Personal Safety

No discussion of caring for the acutely ill and injured would be complete without a reminder to health care providers to look out for their own personal safety and wellness as an initial priority. In caring for an acutely ill or injured patient, there are high risks for exposure to body fluids. Standard precautions should be taken to minimize the possibility for contamination and exposure at all times. The potential for concern should be evaluated to determine the appropriate level of precautions needed. Wearing protective gloves is certainly considered a minimum step, but as the potential for contamination escalates, consideration should be given to masks with eye shields, protective gowns, and so on.

The safety of the care environment should always be a primary consideration. Having adequate police, security, or additional personnel to ensure that the environment is safe for the health care providers is paramount. Although this is especially true in the prehospital care environment, it must also be thought about in the hospital.

As you approach the apparent patient, always perform a brief evaluation to determine whether you are in a safe environment; if not, protect yourself and your patient to limit exposure to possible injury. Assess environmental hazards; the potential of agitation from a delirious patient, causing aggressive action; and other personnel hazards such as family members and bystanders.

While uncommon, if the situation exists in which it is likely that the rescuer(s) could be injured or killed while rendering care, the rescuer should wait until the situation can be made safe. For example, in an automobile accident, a patient trapped in a car in a busy traffic lane should not be given first aid until safety flares or cones can be placed to prevent secondary accidents. Other hazards, such as downed power lines, should be investigated as well.

When providing care in the field, is also important to assess the situation to determine what further resources may be needed to ideally care for the patient(s). Identifying the situation of the patient at the scene may help determine the mechanisms of injury to assist in the diagnostic workup and in treatment for the patient.

The initial task for the health care provider in approaching most, if not all, patients in acute situations involving an unconscious patient is to first ascertain that they are not in cardiopulmonary arrest. If so, summoning help and performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) are the initial priorities. If the patient is not in need of CPR, immediate identification of the causes of their non-responsiveness should be initiated through an organized two-step approach to the rapid patient assessment, which includes a primary survey and secondary survey. This organized approach helps to lend a prioritization to the approach to ensure the major threats to life are identified first. The acceptable approach to these acute, undefined encounters is to consider the patient unstable until you can confirm, through a series of diagnostic steps, that the patient is well enough for you to take the time to perform a more rigorous and complete physical examination and document a complete history.

Current Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Guidelines

For the unconscious patients who are determined to be in cardiac arrest, the health care provider should initiate cardiopulmonary resuscitation according to the guidelines set by the American Heart Association (AHA).

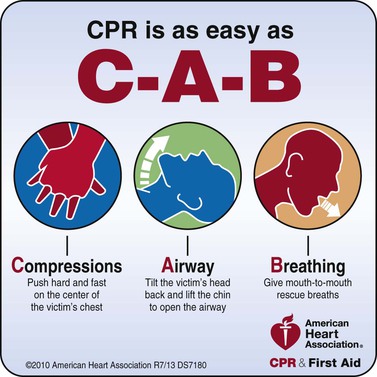

For more than 40 years, emergency teams have always practiced the A-B-C (airway, breathing, chest compression) sequence for resuscitation. In October 2010, the AHA, after many years of research, recommended that the three steps of CPR and emergency cardiac care (ECC) be rearranged. The newest development in the 2010 AHA guidelines for CPR and ECC was a change in the basic life support (BLS) sequence of steps from “A-B-C” (airway, breathing, chest compressions) to “C-A-B” (chest compressions, airway, breathing) for adults and pediatric patients (children and infants, excluding newborns). Figure 23-1 shows the new recommendation.

Figure 23–1 Cardiopulmonary resuscitation survey algorithm. Courtesy of the American Heart Association.

Chest compressions provide blood flow to the heart and brain during a cardiac arrest, and research has shown that delays or interruptions to compressions reduced survival rates. Ventilations are less critical, as victims will have oxygen remaining in their lungs and bloodstream for the first few minutes after a cardiac arrest. Starting CPR with chest compressions can effectively circulate blood to the victim’s brain and heart sooner, with the principal goal of maintaining some amount of oxygenated blood circulating through the brain.

In the original A-B-C sequence, chest compressions were often delayed while the responder opened the airway to give mouth-to-mouth breaths or retrieved a barrier device or other ventilation equipment. By changing the sequence to C-A-B, chest compressions can be initiated sooner and ventilation only minimally delayed until completion of the first cycle of chest compressions (30 compressions should be accomplished in approximately 18 seconds).

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Survey

It should not be assumed that any patient who is not obviously interacting with his or her environment is simply sleeping. For the purpose of this approach, the patient is in cardiopulmonary arrest until it is proved otherwise. As you approach the patient, observe the patient closely, looking for spontaneous breathing or movements. If these are not discernible, stimulate the patient by talking loudly to him or her and gently shaking them while asking, “Are you okay?”

If there is no response or evidence of spontaneous breathing, call for help in any way you can without leaving the patient; it is unlikely that you can manage the entire resuscitation by yourself.

Determine whether there is spontaneous cardiac function by feeling for a carotid pulse for 10 seconds or, in an infant, by palpating the arm for a brachial artery impulse. If there is no pulse, begin external chest compressions, at least 100 per minute.

To open an unconscious victim’s airway, hyperextend the head and lift the patient’s chin; place one hand on the patient’s forehead and the other behind the patient’s occiput, and tilt his or her head backward. This maneuver moves the tongue away from the back of the throat, allowing air to pass around the tongue and into the trachea. Caution should be exercised with any patient who has a suspected neck injury. With such a patient, try to open the airway by lifting the chin and jaw without tilting the head backward; grasp the lower teeth and pull the mandible forward. If necessary, tilt the head back very slightly. If a patient is wearing dentures, remove them only if they occlude the airway.

Summary of CPR Guidelines for Adults, Children, and Infants

Check

CPR

• Push chest at least 2 inches, 30 times in the center of the chest

▪ Push 2-handed, with one hand on top of the other

• Push at a rate of at least 100 pushes per minute

• Allow complete chest recoil after each push

• Limit interruptions in chest pushes to less than 10 seconds

• BREATHE

• Give 2 breaths. Give each breath over 1 second

• The victim’s chest should rise with each breath

Continue Sets of 30 Pushes and 2 Breaths

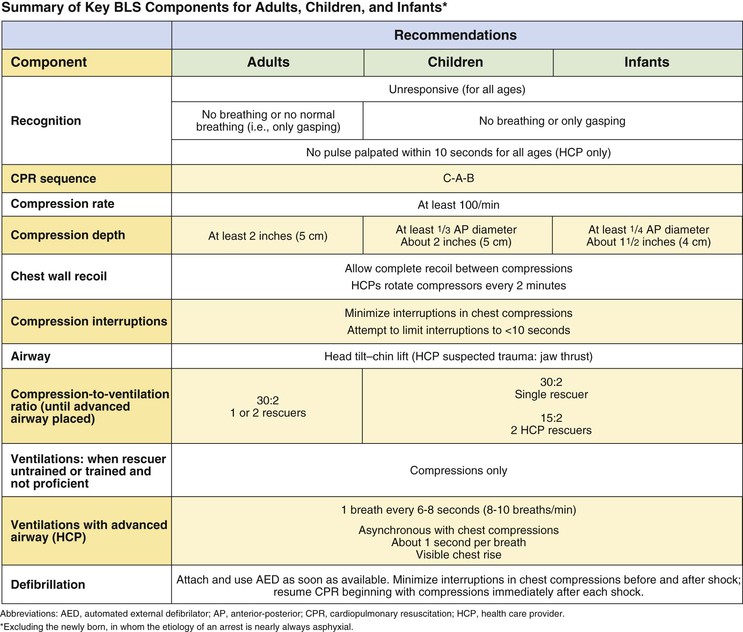

Figure 23-2 is a summary of these key basic life support components for adults, children, and infants (excluding newborn infants).

Figure 23–2 Summary of key basic life support components for adults, children, and infants. From American Heart Association, Hazinski, MF, Chameides L, et al: Highlights of the 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for CPR and ECC. Available at: http://www.heart.org/idc/groups/heart-public/@wcm/@ecc/documents/downloadable/ucm_317350.pdf. Accessed March 28, 2013.

There is continued emphasis on providing high-quality chest compressions. Remember to:

The new recommendation also states that the chest should be depressed at least 2 inches, as opposed to approximately  to 2 inches, which was the recommendation in 2005.

to 2 inches, which was the recommendation in 2005.

There has been no change in the recommendation for a compression-to-ventilation ratio of 30 : 2 for single rescuers of adults, children, and infants (excluding newborn infants). The 2010 AHA Guidelines for CPR continue to recommend that rescue breaths be given in approximately 1 second. Once an advanced airway is in place, chest compressions can be continuous (at a rate of at least 100/min) and no longer cycled with ventilations. Rescue breaths can then be provided at about 1 breath every 6 to 8 seconds (about 8 to 10 breaths per minute). Excessive ventilation should be avoided.

Assessment of the Acutely Ill or Injured Patient

The assessment of the acutely ill patient involves moving through a series of simple evaluations, which are grouped into two categories termed the primary and secondary surveys. The primary survey is a check for conditions that are an immediate threat to the patient’s life. This initial assessment should take no longer than 10 to 15 seconds. The primary survey is subdivided into a cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) survey and a key vital functions assessment. The secondary survey is a check for conditions that could become life-threatening problems if not recognized and attended to.

The primary and secondary surveys are used for both adult and pediatric patients, as well as for medical and injury-related problems. The treatment process is integrated into the diagnostic process. For example, if the patient is not breathing, ventilations are begun immediately, before you move on to the next diagnostic step.

The first task is to recognize when a patient is acutely ill. An unusual appearance or behavior may be the only sign. These include breathing difficulties, clutching the chest or throat, slurring of speech, confusion, unusual odor to the breath, sweating for no apparent reason, or uncharacteristic skin color (e.g. pale, flushed, or bluish).

Remember that an acutely ill patient is anxious and frightened; a calm and reassuring voice can go a long way toward comforting the patient. It is always easier to care for a relaxed patient than for an anxious one.

Primary Survey

Key Vital Functions Assessment Survey

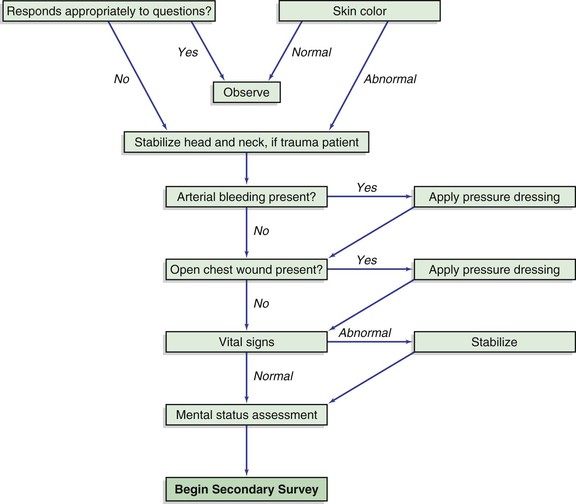

Figure 23-3 illustrates the Key Vital Functions Algorithm. Once it has been determined that the patient does not need CPR or the patient has recovered spontaneous cardiopulmonary activity, ascertain whether key life-sustaining functions are adequate and stable or whether augmentation or other supportive measures are necessary.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree