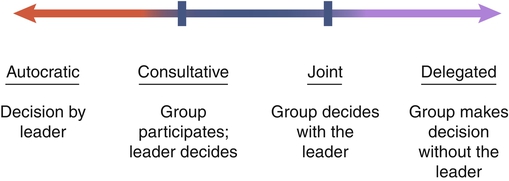

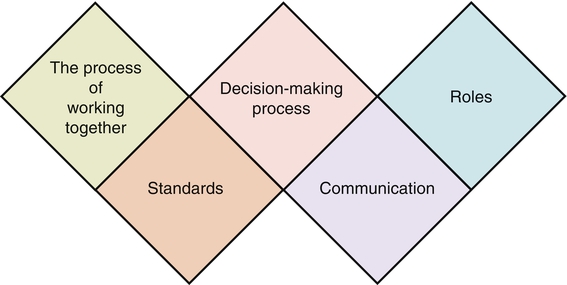

“Knowledge has become so complex and specialized that virtually no single individual can be effective alone” is still true today (Sorrells-Jones & Weaver, 1999, p. 15). Because knowledge workers are specialists, the only way for them to be adequately productive is to work in groups or teams. Thus as the focus shifts to building knowledge work teams, today’s leaders must be able to help these teams be more effective and productive. A team was defined by Katzenbach and Smith (1993) as “a small number of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose, performance goals, and approach for which they hold themselves mutually accountable” (p. 45). Manion and colleagues (1996) modified this definition slightly for health care by noting that the members need to be consistent. This was in reaction to confusion in terminology for many people in health care who had prior knowledge of team nursing, in which whoever was present on a given shift was on the team. In this type of team nursing model, members could vary from shift to shift and from day to day, reducing the overall performance outcomes of the team. Team nursing was an assignment pattern and work allocation methodology rather than a true team model as seen in business and industry. The distinction between a work group and a true team is crucial. Health care leaders may mistakenly assume that simply calling a group a team actually makes it a team. As Katzenbach and Smith (1993) emphasized, the group becomes a true team only by doing its collective work. The team goes through a developmental process that takes time and the investment of energy to materialize. Many collective entities in today’s organizations are called a team yet clearly function more as a work group than a true team. This is in contrast with a true team, which is a collective entity in which the leadership rotates and is shared by various members of the team, depending on appropriateness and fit of skills and abilities. In a true team, there are collective work products—for example, the provision of quality patient care to all of the patients housed in the department. There is group as well as individual accountability. If one member of the team is having a problem, it is not just that person’s problem but, rather, is the problem of and for the whole team to resolve. An example of team thinking is “No one sits down until we can all sit down” or “No one goes home until we all go home.” If quality outcomes are difficult for one team member, all team members are affected by this and become engaged in helping the affected team member meet expectations. In the management book The Goal (Goldratt & Cox, 2004), the author tells a parable about taking a Boy Scout troop on a hike. When it was discovered that Scout Herbie was slowing the whole group down, the weight in his backpack was redistributed and the troop sped up. This is how a high-performing team works. Group interactions are a pervasive element of the health care environment in which nurses work. A basic understanding of groups helps nurses function more effectively. These principles apply to any group, whether an actual team, a committee, or an informal group effort. Group interactions are composed of the following elements (Book & Galvin, 1975) (Figure 8-1): • The process that the group undergoes to reach outcomes: This relates to the unique way the group interrelates and begins to work together. The leader can assess group process through observation. What is the process that occurs while accomplishing its task? • The standards that regulate the group’s behavior: This relates to the specific values and norms that are chosen for group processing. Which ones are chosen and which are discarded? • The process of problem solving or decision making that the group adopts: Does the group solve problems? How are decisions made? Are they group decisions made by consensus, or are they individual decisions made with group input (as occurs when the group participates but the decision is made by a leader or manager)? • The communication that occurs among group members: What are the internal patterns and styles of communication used by group members? To whom does the group communicate? Do they report as a subcommittee to a full committee? If a team, does the team have frequent communication with external team leaders? What are the internal and external modes of communication for group input and output? • The roles played by each member: Members will adopt a variety of group roles within the group, but roles are fluid. Members may take on different roles in different situations. It is important to remember when assessing group interactions that roles in the group may be formal roles, clearly established by the leader or the group. However, there are additionally roles that each group member moves in and out of that best suit him or her (such as clarifier, harmonizer, devil’s advocate, etc.). Clarity in the more formal roles such as team leader, facilitator, recorder, and timekeeper is important to avoid confusion and unnecessary conflict. Groups tend to go through a series of stages in their work and development. Farley and Stoner (1989) originally identified these as (1) orientation, (2) adaptation, (3) emergence, and (4) working. The first stage, orientation, occurs when the group first forms and the members begin to relate to one another and the task. The group needs to develop trust and define boundaries in order to establish involvement and identification. The second stage, adaptation, occurs as the group begins to develop a collective identity and differentiate roles. The group needs a facilitative structure and climate to maximize its processing and to work through the establishment of roles, rules, norms, and a common language. The third stage, emergence, occurs as control issues arise. Disputes, disagreements, confrontations, alliances, and power struggles mark this stage of determining control over the group in order to emerge with a more consolidated identity. The final stage, working, occurs when conflict and dissension dissipate and the group achieves greater cohesion through negotiation. The group is now focused primarily on decision making and productivity. The stages may overlap and are not necessarily sequential. The group leader pays attention to the stage of the group as a way of monitoring the group’s development and progress. For example, in the orientation stage, the leader may need to be more alert to the need to intervene personally than would be the case in the working stage when the group has achieved a higher level of maturity. • Group activities can create a sense of status and esteem. • Groups allow an individual to test and establish reality. • Groups function as a mechanism for getting a job done. • The work to be accomplished requires the complexity of knowledge and skill possible only in a group configuration. “The ebb and flow of work done by groups is a major part of the working environment of hospital nurses” (Leppa, 1996, p. 23). The work group provides an institutional and professional identity for an individual nurse, and work groups become a focus for interpersonal relationships, support, and social integration. Interpersonal relationship elements such as work group cohesion, communication, and social integration remain consistent moderate-level predictors of nursing job satisfaction (DiMeglio et al., 2005). In addition, being part of a healthy group or team is also related to the level of organizational commitment by the employee. Individuals with an emotional connection to their work group have lower levels of turnover and higher levels of engagement (DiMeglio et al., 2005; Manion, 2004, 2009). Work groups can be disrupted by factors such as downsizing, reorganization, absenteeism, and turnover. Work group disruption has been shown to be linked to negative outcomes (Leppa, 1996; Kalisch & Begeny, 2005; Kalisch et al., 2008; Kalisch & Lee, 2010). In a study of four hospitals, interpersonal relations were found to be an important part of nurses’ job satisfaction. There was a relationship between work group disruption and interpersonal relations (Leppa, 1996). Things get done because of relationships among people; nurses need to build successful collaborative relationships among multiple levels of colleagues, key people, organizations, and clients (Laramee, 1999). The level of nursing teamwork has been found to be directly linked to missed nursing care (Kalisch & Lee, 2010). Furthermore, informal work group norms exert a strong influence on nurses’ behavior and can contribute to forms of nursing deviance. Work group relationships can reinforce behaviors and rationalization, thus leading to deviant behaviors becoming passively or actively accepted. For example, in one study of nurses in practice, nurses used work group norms to neutralize opposition to drug theft and use (Dabney, 1995). Clearly, there is a strong relationship between work groups, interpersonal relationships, and outcomes such as nurses’ behaviors and perceptions. Work group relationships are a powerful mechanism influencing both good and bad outcomes in nursing practice. There are advantages to group work. For example, groups are one vehicle for solving problems. Veninga (1982) identified the following five major advantages of group problem solving over individual problem solving: 1. Greater knowledge and information: Obtaining a broader and wider range of knowledge and experiences creates a higher-quality input into group problem solving. The insights of one member can stimulate the thinking of other group members. With today’s highly specialized health care workers, this is especially true. 2. Increased acceptance of solutions: If there is a decision to be made in an organization, people can get together in a group to talk about it so that the people themselves are more committed to the decision. When individuals who are going to be affected by a decision are part of the decision-making process, they do not have to be convinced of the rightness of the decision and are more likely to be committed to implementing it. 3. More approaches to a problem: Complex problems typically are more manageable when a number of perspectives are mixed together to address the problem. The advantages include blending and complementing individual learning and problem-solving styles to capitalize on strength through diversity. 4. Individual expression: Groups allow for individual expression, and in organizations specifically, there may be few mechanisms for expression of individual perspectives. Sharing information and getting input are done best in groups (Veninga, 1982). Sometimes groups allow people to express themselves—for example, if they are anxious about a change or if morale is low. 5. Lower costs: If the group is functioning in a positive and constructive manner, the use of a group can be less expensive than the use of individual effort to accomplish a task. Group decision making is cost-effective if it saves time. For example, when a group meets for one session as opposed to the leader meeting multiple times with multiple individuals, the leader and possibly the group members save time. Group decision making can be derailed at a number of points in the process. The three disadvantages commonly noted about group decision making are the potential for premature decisions, individual domination, and disruptive conflicts (Veninga, 1982). In addition, a continuum of decision-making power may be vested in a group (Figure 8-2). A group or committee has certain powers, tasks, and functions, as well as certain parameters or latitude in terms of how far to go in making a decision. Decision power is a matter of degree, with four distinct points on the continuum of authority for decision making: autocratic, consultative, joint, and delegated. Three types of teams found in health care are (1) primary work teams, (2) leadership teams, and (3) ad hoc teams (Manion, 2011). Primary work teams include all forms of client care teams such as an emergency department trauma team. In the operating room, teams are often based on the specialty (e.g., a cardiovascular or an orthopedic team). The senior executive team is an example of an executive or management leadership team. At the hospital department level there may be a leadership team that is composed of the nurse manager, charge nurses, and perhaps an educator. Continuous quality improvement teams, project teams, and problem-solving teams are examples of ad hoc teams found across settings and sites. Specific problem-solving teams in departments are other examples of ad hoc teams. The chief characteristic of these teams is that they are created to perform a very specific piece of work. When that work is completed, the team dissolves. Designing, building, and implementing effective work teams requires a specific methodology and process. A primary work team fails if it behaves like a collection of individuals operating from narrowly defined jobs; if it is composed of the wrong mix of members, size, structure, responsibility, or expertise; or if it cannot fluidly shift activities and adapt to changes. Teams should be designed based on the work responsibilities of the team. After the team design is determined, the next step is to build the team by incorporating the essential elements needed to function. These include a common purpose; agreed-on performance goals or results-driven structure; competent members; a common approach for the work; complementary skills; a collaborative relationships; mutual accountability; standards of excellence; external support; and principled leadership (Manion et al., 1996). The complementary skills that are needed, in the right mix, to do the team’s task fall into at least three categories: technical or functional expertise, problem-solving and decision-making skills, and interpersonal skills (Box 8-1).

Team Building and Working with Effective Groups

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Huber/leadership/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Huber/leadership/

DEFINITIONS

BACKGROUND

WHY GROUPS ARE FORMED

ADVANTAGES OF GROUPS

DISADVANTAGES OF GROUPS

GROUP DECISION MAKING

WORKING WITH TEAMS

Types of Teams

Team Building and Working with Effective Groups

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access