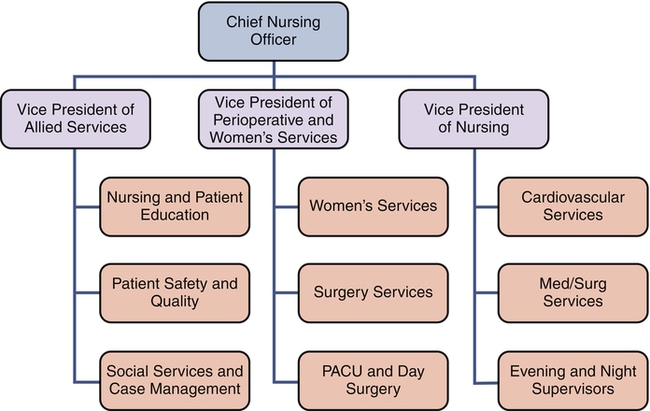

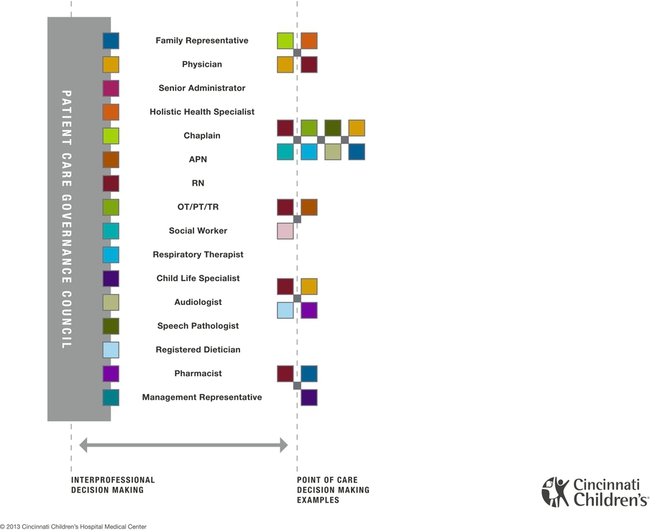

In early 2012, Google created an online petition to halt two anti-piracy bills that would censor parts of the Internet. Popular websites like Wikipedia blacked out their content in protest, and 4.5 million people sided with the websites and signed the petition. The overwhelming requisition caused 18 U.S. senators—including some of the bill’s own co-sponsors—to reverse their positions of support (Kain, 2012; Tassi, 2012). Social media and other advents in technology like smart phones and Wi-Fi have made it easier for the majority to voice their opinions, but the desire to communicate is nothing new. Plato himself believed the only way to reach the truth was by dialogue (Poe, 2011), yet it took centuries before the voices of the masses were heard. In the nineteenth century, the labor rights movement encouraged workers to address fair treatment and safe work environments. In the 1960s, organizational theorists Herzberg and McGregor championed employees as the most important asset of an organization, and they encouraged companies to invest in their motivation and growth (Anthony, 2004). This paradigm shift caused companies to view employees not as a means to an end, but as a potential source of innovation and creativity if the environment fostered such ideals. The mission, core values, and vision are the instruments that give voice to the organization’s philosophy. The mission is an aim to be accomplished. It influences the philosophy, goals and objectives of an organization. The vision is a mental image or the power of imagination to see something that is not actually visible. Likewise, the organizational chart is a diagram that displays how the parts of an organization are connected. It shows organizational relationships and areas of responsibility (Tomey, 2009). If there are many layers of management with reporting lines cascading down from the top, then the structure is hierarchical. Figure 14-1 illustrates an example. At a glance, the chart permits the trained observer to make a statement about the organizational philosophy of the organization—whether the authority is primarily centralized or decentralized (Straub & Attner, 1994). Centralization and decentralization are organizational philosophies about power distribution that pertain to the hierarchical level of decision-making authority in the institution. Centralization means that decisions are made at the top levels. Decentralization means that decision making is diffused throughout the organization. The higher the degree of decentralization in an organization, the more decision making is done at lower levels and with less supervision. Institutions organize and structure themselves by defining departmental function and authority to achieve a more coordinated effort. It drives plans and decisions about responsibilities and who reports to whom. Executives may use selective decentralization, where power for decision making is concentrated in the functional areas of staffing, purchasing, and operations, for example (Kops, 2011). Alternatively, they may choose to set purchase limits at each level of the organization by dollar amounts. Centralization and decentralization are relative terms when applied to the operating philosophy of institutions. In institutions where the executive leader retains more decision-making authority, the operation takes on a more centralized philosophy. However, as institutions evolve into more complex global operations—where nurse managers are held accountable for transactional processes such as budgets, productivity, and quality monitoring, on top of their roles as coaches, mentors, and leaders to staff nurses (McGuire & Kennerly, 2006)—it becomes difficult for them to manage the information overload. An institution with centralized decision making is demonstrated in the first scenario as follows: The professional staff nurses are involved in making a hiring decision that directly impacts their workplace in the second scenario. This scenario clearly illustrates a more decentralized organizational philosophy. In such an organization, decision-making authority rests in levels closer to the point of service rather than in the executive levels. Decentralization encourages and facilitates greater innovation, more input, and faster response times. “Decision-making that is decentralized and collaborative is an essential component in care environments that support excellence in patient care” (Golanowski et al., 2007, p. 342). It is important to note that, although the two examples would appear distant from one another, many institutions exhibit varying degrees of centralization or decentralization. The core distinction is: decentralized to what level? Span of management is the number and diversity of people who report to a manager. The degree of decentralization may vary from minimal to maximal. Centralized decision making results in a narrower span of control and more levels of management, whereas decentralized decision making generally means that the span of management is larger for each manager (Tomey, 2009). Managers who delegate authority find that they can devote more time to planning and evaluating outcomes. Fewer levels of management will be required because the staff take on great accountability for decisions at the point of service, or operational level. Institutions that employ a decentralized organizational philosophy emphasize planning and evaluation, and communicate clear goals and objectives to their employees. Therefore they are more likely to develop synergy within the institution. Synergy results from bringing different perspectives together in a spirit of mutual respect to seek the best solution, because the whole is greater than the sum of its parts (Tomey, 2009). Shared governance is “a dynamic process for achieving organizational effectiveness by promoting decision-making and accountability for practice through empowerment” (Bednarski, 2009, p. 585). It is more than just a framework; it is a partnership between management and clinical staff (Frith & Montgomery, 2006). Advocates of shared governance argue that it is a strong foundation to create a framework for excellence and address the needs of a nursing practice-driven environment by reallocating power in the organization to those who do the work (Porter-O’Grady, 2009). Research suggests that registered nurses who are empowered to make decisions through shared governance have higher nurse autonomy and increased confidence in decision making (Newman, 2011, Tourangeau et al., 2006). Kanter’s (1993) theory of organizational empowerment provides the theoretical underpinnings for shared governance. Her theory asserts that social structures in the workplace have a larger impact on attitudes and behaviors than do individual personalities. Kanter suggested that avenues of power provide for the sources of structural empowerment in an organization. Avenues of power include access to information, access to resources required to do the job, having the opportunity to learn and grow, and being supported. In addition, she suggested that the informal job factors that influence empowerment are the alliances that workers have with fellow workers at all levels of the organization. Workplaces that are structurally empowering provide many of the opportunities for involvement, commitment and transparency. Empowered workers are more likely to have increased feelings of respect for and trust in management and organizational justice, which relates to one’s commitment to an organization (Moore & Hutchison, 2007) and may impact retention, which ultimately affects recruitment. Decentralization and shared governance were strategies first introduced in the late 1970s to enable nurses to exercise control and make decisions about their practice, as a means to promote relationships and responsibilities between nurses and the organizational leaders, as well as develop equality and parity. Shared governance is touted as a strategy to transform organizations, improve productivity, empower staff nurses, enhance staff nurse autonomy, increase job satisfaction, and reduce nursing turnover (Anderson, 2011). This was seen as a radical departure from the traditional hierarchical hospital management structure in which nurses had little authority, little voice in governance, and low control within the organization (Hess, 1994). Shared governance is not a theory, a conceptual framework, or an organizational principle. Shared governance is a vehicle for engaging organizations and creating the necessary forums and intersections that assure the decisions and actions remain dynamic and as close to the point of service as possible (Porter-O’Grady, 2009). It is an accountability-based model through which nurses actively engage in making decisions regarding nursing practice, quality of patient care, education, nursing peer issues, and issues in the work environment. Shared governance promotes involvement, investment, participation, sharing of power, interdependence, cooperation, horizontal relationships, autonomy, and accountability for nursing decisions. Nursing effectiveness is enhanced through the sense of ownership that comes with more active involvement in the leadership of the organization. Professional practice environments, known for their improved patient outcomes, are characterized by institutions in which nurses have a high level of autonomy, strong leadership, support from administration, and control over their practice, all of which are results of shared governance (Tourangeau et al., 2006). Shared governance is seen as a strategy for fostering professional nursing practice through empowerment of nurses. The degree of nurse participation in decision making varies with shared governance models and may range from minimal, or informal participation, to true sharing of authority and accountability. Porter-O’Grady and colleagues (1997) developed the councilor model as a focus on shared governance. The councilor model structures staff and manages governance through the use of committees or councils of elected representatives. Each council is responsible for certain functions and has clearly defined authority. Councils within nursing may include practice, quality improvement/inquiry, education and management. Figure 14-1 displays the councilor model as it is defined in one large teaching hospital in a metropolitan area. At its start, shared governance requires the education and support of organizational executives, managers and point of care staff. All levels of an organization must collaborate on a shared purpose to become innovative and efficient (Adler et al., 2011). The challenge for administrators is not in creating the structure that supports shared governance but, rather, in developing a culture that supports, encourages, and maintains it. More than just the structure needs to be created; the philosophy of accountability must be implemented as well (Anderson, 2011). Perhaps the greater challenge for administrators is justification of the cost in terms of personnel time, effort, and financial commitment. The chief nursing officer needs to build the cost of maintaining shared governance into the operational budget for it to become successful. Shared governance “is truly a journey, not a destination; a process, not a project” (Frith & Montgomery, 2006, p. 282). It is a dynamic process, one that is constantly changing. It changes as the organization, personnel, and time change. “Because shared governance is a continuum, people need to be met where they are on their journey and coached to progress to the next point” (Moore & Hutchison, 2007, p. 566). Education must be continually available to employees in institutions that practice shared governance. Programs are needed to instruct new employees and newly elected unit representatives, to continually develop leadership behaviors in nursing staff, and to support and guide nurse managers. Educational programs should include consensus building and conflict resolution; planning and conducting effective meetings; successful communication techniques and skills; collecting, aggregating, and displaying meaningful data; and strategies for successful problem solving. Nurse managers are key in determining the degree of shared decision making that will actually occur at the unit level. Those managers willing to relinquish control are likely to find additional time for coaching and mentoring, as well as for planning and strategizing. Evidence also shows shared governance plays a part in developing future nurse leaders (Beglinger et al., 2011), so the nurse manager must foster the development of leadership behaviors in staff nurses. If governance is restricted to the level of the nursing unit, staff autonomy and participative decision making may increase without affecting the overall organizational structure (Hess, 1994). Thus initial identification of spheres of influence and boundaries associated with shared governance is important to prevent frustration (Ballard, 2010). Accountability must always be located at the place where decisions are most appropriately made for shared governance to work (Porter-O’Grady, 2009, p. 55). If an institution employs a shared governance model in which patient care quality is truly the primary focus and clinical staff members are empowered as decision makers, this will be reflected in both the organizational chart and resource allocations. One example of such an organizational chart is depicted in Figure 14-2.

Decentralization and Shared Governance

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Huber/leadership/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Huber/leadership/

DEFINITIONS

Centralization and Decentralization

SHARED GOVERNANCE

History

Implementation

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Decentralization and Shared Governance

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access