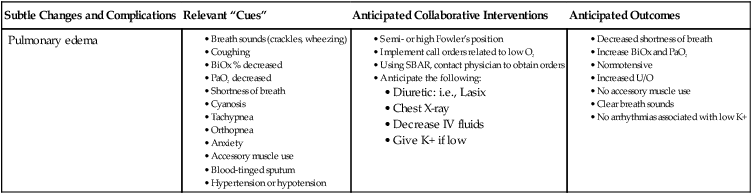

18 Lillian Gatlin Stokes, PhD, RN, FAAN and Gail Carlson Kost, MSN, RN, CNE The environment for practicum experiences may be any place where students interact with patients and families for purposes such as acquiring needed cognitive skills that facilitate clinical decision making as well as psychomotor and affective skills. The practicum environment, referred to as the clinical learning environment (CLE), is an interactive network of forces within the clinical setting that influences students’ clinical learning outcomes. The environment also provides opportunities for students to learn to apply theory to practice and to become socialized into the expectations of the practice environment, as well as the roles and responsibilities of health care professionals. To accomplish these outcomes, a variety of experiences are required in multiple settings. These settings may be special venues within schools of nursing or within acute care settings or communities. It is essential that practice environments be supportive and conducive to learning so that students will develop the qualities and skill abilities needed to become competent professionals (Williams, 2001). The following section describes these settings. Included among these are practice learning centers such as learning labs, acute and transitional care, and community-based environments. To foster a nonthreatening and safe learning environment, the practice learning center is used at several stages of students’ learning. These centers encourage guided experiences that allow students to practice and perfect a variety of psychomotor, affective, and cognitive skills such as critical thinking and clinical reasoning before moving into complex patient environments. Simulation is one example of a teaching method used in the practice learning center. This method is increasingly used to evaluate knowledge acquisition as well as skill sets (Childs, 2002). According to Rush, Dyches, Waldrop, and Davis (2008), “Simulation is a strategy increasingly being used to promote critical thinking skills among baccalaureate nursing (BSN) students.” Schiavenato (2009) also states, “The human patient simulator or high-fidelity mannequin has become synonymous with the word simulation in nursing education” (p. 388). Bremner, Aduddell, Bennett, and VanGeest (2006) believe that the incorporation of high-fidelity mannequin technology is one of the most important issues in nursing education today. Simulation may assist in supplementing didactic content in the classroom or it may be used to ensure that all students in a clinical course would experience a patient situation that may not be available during the regular clinical day. Schools across the country are increasingly using human patient simulators for teaching a part of a student’s clinical nursing course. When evaluating the effectiveness of this teaching strategy, those involved need to determine what was learned and gained in the experience and what knowledge will be transferred to the real clinical setting, which will ultimately affect patient care. There are variations among Boards of Nursing as to the use of simulation in the curriculum. (See Chapter 20 for further discussion of simulations.) Given the challenges of finding sufficient clinical experiences for students, faculty are exploring the use of virtual clinical experiences made possible by online technologies such as Second Life that can create virtual clinical environments (Schmidt & Stewart, 2009) and use existing technologies such as e-ICUs and telehealth capabilities to create opportunities for additional clinical experiences. According to Grady (2006), “Nursing education practices have changed little in response to massive and sweeping changes in the complex and dynamic health care environment” (p. 125). Research has been conducted to better define and “test leading-edge telehealth methods and technologies that can extend the reach of nursing in clinical areas as well as classroom settings” (p. 124). The Virtual Clinical Practicum (VCP) was designed to provide a live, clinical experience to nursing students from a distance. Students gain clinical experience and practice skills and clinical judgment using telehealth technologies in which students observe a nurse taking care of a patient in a clinical setting without going to the actual clinical site. The students can interact with the nurse and patient using telehealth technology. The VCP process was developed as a potential solution to expanding nursing school enrollment to accommodate the nursing shortage in the face of limited clinical practice sites as well as limited clinical experts, especially in rural areas. (See Chapter 21 for further discussion of virtual environments.) The complexity of the environment also provides opportunities for faculty to become facilitators of learning, designers of clinical experiences, and developers of flexible skill sets that can be used across settings. Faculty must provide experiences to help students think, care, and act like nurses—and finally to be nurses (Tanner, 2002). For this to occur, the outcomes for specific learning experiences must be clearly identified and articulated. The health care delivery system is continuing to shift from acute care hospital environments to the community. Several factors have facilitated this shift, including social, technological, and economic changes as well as the politics of health care. These changes have resulted in an increased use of community agencies such as ambulatory, long-term, home health, and nurse-managed clinics; homeless shelters; social agencies (e.g., homes for battered women); physicians’ offices; health maintenance organizations; worksite venues (Schim & Scher, 2002), art galleries; day care centers; and schools (Buttriss, Kuiper, & Newbold, 1995; Chan, 2002; Faller, McDowell, & Jackson, 1995). Summer camps are also being used for special experiences (Totten & Fonnesbeck, 2002). Depending on the purpose of the camps, multiple objectives can be accomplished. For example, camps for children with health issues can be used for acquisition of targeted skills that could be obtained in acute care settings. Camps for healthy children could be used for acquisition of knowledge and skills relating to normal growth and development and communication. Despite all efforts on the part of classroom and clinical faculty, there seem to be times of “great divide” between the two arenas. Benner, Sutphen, Leonard, and Day (2010) indicate that “even with faculty commitment to integration, all too often, nursing education is approached as if it has two discrete elements” (p. 159). Dual clinical and classroom assignments for faculty will assist in making those necessary connections between clinical and classroom. “The very strength of pedagogical approaches in the clinical setting is itself a persuasive argument for intentional integration of knowledge, clinical reasoning, and skilled know-how and ethical comportment across the nursing curriculum” (Benner et al., 2010, p. 159). Thus faculty have a significant role in helping students to make the necessary connections between clinical and classroom experiences. According to Piscopo (1994), “roles identify relationships and are interactional and reciprocal” (p. 113). The ability of the clinical faculty to facilitate students’ learning can be enhanced when an effective working relationship is established within the clinical agency. Effective relationships begin with effective communication, which must be practiced in an ongoing manner to maintain relationships and facilitate learning (Lee, Krystyna, & Williams, 2002). This requires having an understanding of the environment and the roles of the individuals within the environment, and a realization that these do not exist in isolation but are patterned to dovetail with or complement other roles. Clinical experiences provide opportunities for students to practice the art and science of nursing, which enhances their ability to learn. To maximize these experiences, faculty must have full knowledge and understanding of each student (see also Chapter 2). The nursing student population is culturally diverse and includes members of varied age groups, many ethnic and racial groups, and an increasing number of males. This population is also likely to include persons with (or without) prior degrees from a variety of disciplines, as well as those who possess many different health care experiences and technological skill levels. In addition, students differ in their learning styles, levels of knowledge, and preferences for learning opportunities; therefore faculty must make concerted efforts to balance the students’ learning needs, interests, and abilities when selecting clinical experiences without losing sight of the curriculum and expected competencies and outcomes. Such action can be facilitated by making an assessment of the knowledge, culture, and skills of the learner. Such an assessment helps the faculty determine whether students possess the cognitive, critical thinking, clinical reasoning, decision-making, psychomotor, and affective skills needed for the experiences. The clinical environment has been described as a place where students synthesize the knowledge gained in the classroom and make applications to practical situations. Chan (2002) describes the clinical learning environment as “the interaction network of forces within the clinical setting that influences student learning outcomes” (p. 70). A number of forces affect expected outcomes, including the increased complexity of care required by patients with higher acuity, the nursing shortage, the rapid pace, and multiple health care professionals and activities. These forces, coupled with the need to adjust to an environment that requires an integration of thinking skills and performance skills, often result in increased anxiety among students. Clinical strategies can be developed to reduce anxiety in clinical environments, especially where anxiety levels are high. Some strategies focus on the level of students. Two such strategies are (1) peer coaching, in which senior students coach beginning students (Broscious & Sanders, 2001), and (2) placement of students in long-term care settings. Regardless of location of the practice setting, faculty and staff should provide an environment in which caring relationships are evident. The clinical practice environment should be a place where students feel that they are accepted and that their contributions are appreciated by individuals with whom they interact (Chan, 2002). Attributes of staff such as warmth, support in obtaining access to learning experiences, and willingness to engage in a teaching relationship are considered helpful. Learning to collaborate with the many health care groups involved in patient care can be a daunting task. It is believed that the use of interdisciplinary simulations may assist students in health care disciplines such as nursing, medicine, pharmacy, and respiratory therapy to learn about the clinical management of a variety of patients. Rodehorst, Wilhelm, and Jensen (2005) indicated that the use of interdisciplinary learning helps to clarify the roles of each discipline and enhances learning from one another. As faculty begin to plan the clinical experience, it is essential to determine the goal of the particular clinical experience for that day. For the beginning student, focused clinical experiences in which the student is to accomplish specific objectives and to achieve specific competencies and individual learning needs are appropriate (Gubrud-Howe & Schoessler, 2008). If that is the goal, faculty would plan for a focused clinical experience. Specifically, students may interview patients to work on communication skills, perform vital sign assessments to develop this particular skill set, observe in a specialty area, and give and receive reports. The focus of each experience is some needed skill set for students’ or an individual’s learning needs. Other learning goals may emphasize facilitating students’ ability to synthesize information, integrate didactic and clinical knowledge, develop clinical reasoning and judgment skills, and plan care for groups of patients (Benner et al., 2010; Tanner, 2010). Here, assignments that involve planning care for patients with complex needs and for multiple patients are appropriate. These integrative clinical experiences prepare students for transition to practice and typically occur toward the end of the program. Students are required to demonstrate multiple behaviors in cognitive, psychomotor, and affective domains. Consequently, clinical faculty must evaluate students in each of these areas. The evaluation must be both ongoing (formative evaluation), to assist students in learning, and terminal (summative evaluation), to determine learning outcomes. Constructive and timely feedback, which promotes achievement and growth, is an essential element of evaluation. For a discussion of clinical performance evaluation, refer to Chapter 27. Although faculty schedule clinical practicum experiences to promote learning, there is ongoing dialogue about the best way to schedule experiences, with emphasis placed on the length of the experiences (hours per day, number of days per week, number of weeks per semester), the timing of the experiences in relation to didactic course assignments, and student needs. Porter and Feller (1979) examined the achievement of baccalaureate nursing students who either had clinical experience in two alternating clinical sites over a 16-week period or had experiences at one site for 8 weeks, followed by experiences at a second site for the last 8 weeks. No differences in scores on National League for Nursing Achievement Tests were found. Similarly, Dunn, Stockhausen, Thornton, and Barnard (1995) reported that no differences in clinical learning outcomes occurred when clinical assignments occurred either 1 or 2 days per week or in alternating 2-week blocks of time. Often students reported being frustrated by nonsequential clinical experiences because of the inability to form relationships with nursing staff and mentioned that they might provide an intervention in the morning but never are at clinical long enough to evaluate the effectiveness of that intervention. Schools are now rethinking the length of the clinical day and the need to experience a typical nurse’s daily schedule. When the learning goal is to integrate students into a clinical setting or when the students are working with a preceptor, students may work the same shift as the nurse with whom they are paired. Some acute care hospitals have a 12-hour shift option while others have only 12-hour shifts. Giving students the opportunity to work the 12-hour shift affords the full scope of practice in any given nurse’s day. Students are able to quickly see and experience the role of the nurse. In one small study of senior nursing students in a second degree program working a 12-hour shift, Rossen and Fegan (2009) found that benefits included that students felt accepted by staff, had better socialization, and experienced a realistic work environment; disadvantages included decreased teaching time from the faculty. While a shorter clinical day allows for skill acquisition, there is little time for the development of extensive critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and evaluation of care. According to Miller (2005), it is critical that students have adequate time on any given unit to progress beyond the minimum and to be exposed to the unit’s structure, operations, and culture. Additionally, students described positive aspects of the clinical experience as having an experience at a particular organization, the clinical experiences, and the timing of assignments on work and family responsibilities (Dunn et al., 1995). Research about clinical teaching over time consistently indicates that effective clinical teachers are clinically competent, know how to teach, have collegial relationships with students and agency staff, and are friendly, supportive, and patient (Hanson & Stenvig, 2008; Oermann, 1996; Sieh & Bell, 1994; Stuebbe, 1990). Morgan and Knox (1987) and Nehring (1990) found that the best clinical teachers exhibit expert clinical skills and judgment. Skills such as these have been described by students as being particularly important. Students tend to describe effective clinical teachers as those who demonstrate nursing competence in a real situation. Being knowledgeable and being able to share knowledge with students in clinical settings are essential. Such knowledge includes an understanding of the theories and concepts related to the practice of nursing. Equally important is an ability to convey the knowledge in an understandable manner. Karuhije (1997) directs attention to three discrete teaching domains that will facilitate acquisition of the teaching skills needed to foster success in clinical settings: instructional, interpersonal, and evaluative. Instructional refers to approaches or strategies used to facilitate a transfer of knowledge from didactic to practicum. Strategies may include questioning and peer or patient teaching. Faculty should be cognizant that the type of questions can cover a range during exchanges with students. Faculty should also be mindful of the manner in which questions are constructed in order to facilitate positive effects on learning. Questions that ask students to analyze information result in more learning than simple recall. In clinical practice, factors such as the nature of the situation and available time are likely to influence the types of questions raised. Refer to Box 18-1 for examples. Effective clinical teaching requires educators to facilitate students as they learn clinical reasoning skills. Clinical reasoning is a process that enables an individual to collect data, solve problems, and make decisions and judgments to provide quality nursing care in the workplace. Effective and efficient clinical reasoning requires knowledge, skills, and abilities grounded in reflection; is supported by an individual’s capacity for self-regulation; and leads to the development of expertise (Kuiper, Pesut, & Kautz, 2009). Clinical reasoning occurs when an individual has the ability to reason the details of a particular clinical situation. It is believed that students struggle with the ability to make sound judgments. The novice student does not have the ability to identify the subtle or relevant cues seen in a patient whose health condition is changing and for whom complications are beginning to occur. Faculty can assist students in identifying these subtle and relevant cues and start to collaborate with other health care professionals to provide the interventions needed to eliminate or treat these complications. See Box 18-2. Feedback, an essential element in teaching and learning, is described as information communicated to students as a result of an assessment of an action by students (Bonnel, 2008). Feedback, when properly delivered, has a high potential for learning and achievement. In clinical practice where assessments need to be made about the extent to which clinical competencies are met, clinical faculty have a variety of opportunities to offer feedback in response to performance behaviors relating to psychomotor as well as cognitive and affective actions. Regardless of the action, there are key considerations that should be practiced. These considerations are specificity, timing, consistency, continuity, and approach. Approach is important because of its capacity to alleviate anxiety and enhance engagement. Refer to Boxes 18-3, 18-4, 18-5, and 18-6 for information about the delivery of feedback.

Teaching in the clinical setting

Practice learning environments

Practice learning centers

Simulation

Virtual clinical practica

Acute and transitional care environments

Community-based environments

Selecting health care environments

Building relationships with personnel within health care agency environments

Clinical practicum experiences across the curriculum

Understanding the student

Understanding the clinical environment

Selecting clinical practicum experiences

Evaluating experiences

Scheduling clinical practicum assignments

Effective clinical teaching