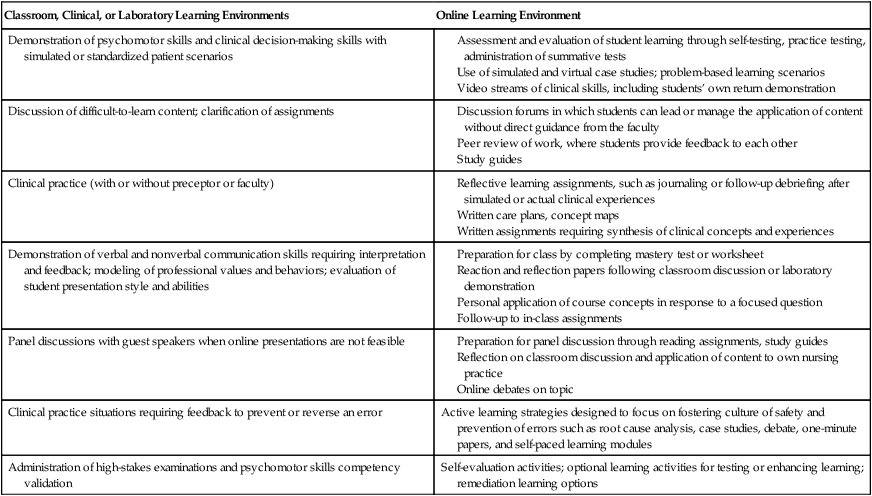

Judith A. Halstead, PhD, RN, ANEF, FAAN and Diane M. Billings, EdD, RN, FAAN Online education is assuming an increasingly prominent role in higher education within the United States. Allen and Seaman (2010), in the 2009 Sloan Consortium online education survey, reported that in fall of 2008 more than 4.6 million college students were enrolled in at least one course where 80% or more of the content was delivered online. This represents an increase of 17% from the previous year’s survey. More than one in four college students report taking at least one online course during their time in higher education (Allen & Seaman, 2010). The growing influence of online learning has global significance as well, creating interconnected learning communities that span the world. Bonk (2010) references the “Web of Learning,” in which the use of web technology is enhancing how people learn worldwide and empowering them to take advantage of learning opportunities that previously did not exist for them. The online courses and programs offered on today’s college campuses are just as likely to attract students who are living on campus as those who live at a distance. This increased use of online learning in higher education has occurred for a number of reasons. The learners of today expect ready access to course offerings and flexibility in scheduling to meet their educational needs (Parker & Howland, 2006). The current generation of college students, many of whom have been raised in the digital age (Lahaie, 2007a) and have already grown accustomed to learning in ways that are supported by technology, is seldom intimidated by the computer and fully expects faculty to incorporate technology into their classroom learning activities. The nursing shortage, the improving quality of available technology, and existing evidence that learning outcomes from in-class courses and online courses are similar are other factors that have contributed to the proliferation of online learning (Baldwin & Burns, 2004). Online learning has a significant presence in nursing education with an ever-expanding number of programs being offered online, especially for those students who are seeking BSN completion degrees and graduate degrees. Providers of continuing education programs are also using online technology to reach larger audiences of health care professionals who appreciate the flexibility and convenience of having their educational needs met in their own homes. Many nursing faculty are integrating aspects of online learning into courses that are primarily taught in the classroom in “real time,” thus creating blended or hybrid courses that maximize the use of web-based learning resources. Online learning has revolutionized higher education and continuing education, erasing place and time boundaries for institutions, students, and faculty. As such, online learning is emerging as one strategy that can be used to effectively facilitate interprofessional education in the health professions (Luke et al., 2009). Online learning is also facilitating the development of an international learning community within the nursing profession, as nurses from around the world can access educational offerings to meet their learning needs. Online learning uses the Internet paired with the capabilities of learning management system (LMS) software to create a learning environment in which a community of learners and educators, as well as other content experts such as clinicians and patients, gather for the purposes of teaching and learning (Babenko-Mould, Andrusyszyn, & Goldenberg, 2004; Jafari, McGee, & Carmean, 2006). Online learning takes place in a virtual learning environment that is created by learning management systems (e.g., WebCT, Blackboard eCollege, Desire2Learn, Moodle). These learning management systems use software to manage teacher–student interactions through the use of such integrated features as discussion forums, chat rooms, audio and video streaming capabilities, e-mails, announcement pages, posting of course documents (e.g., syllabi, assignments), and shared workspaces. E-learning environments have capabilities to integrate podcasts and vodcasts, multimedia, wikis, web logs (blogs), voice threads, and Short Message Service (SMS) tools (instant messaging) (Dell, 2002; Jafari et al., 2006) (see Chapters 21 and 22 for further discussion of these online tools and products). These virtual learning environments are designed to enhance collaboration and interaction through use of shared workspaces and mobile wireless devices and to provide a full complement of learner support through access to academic advisers, mentors, preceptors, and librarians. The learning management systems also typically include assessment and evaluation software such as test generation and administration software, plagiarism detection software, portfolio management software, and online grade books with grade calculation. Additionally, the online learning environment is becoming more integrated with campus services such as the bursar and registrar, thus enabling students to register for courses and receive grades and transcripts (Nelson et al., 2006). In nursing education, online learning is frequently used to offer individual courses and complete degree programs for academic credit. In clinical settings, online learning may be used to facilitate orientation to clinical practice, meet requirements for mandatory continuing education, and create learning communities to support career development, mentoring, and coaching programs for nurses (Billings et al., 2006; Pullen, 2006). Online learning is a popular means by which nurses participate in lifelong learning and obtain continuing education contact hours. Educators and learners use the capabilities of online learning in various ways. For example, content may be developed in self-contained learning modules, or tutorials. Online learning modules typically contain objectives, learning outcomes, learning activities, and an evaluation component. Because of their self-contained nature, learning modules are flexible and lend themselves to multiple uses. For example, learning modules are useful for providing access to information that can be learned without interaction with faculty or classmates and colleagues. Learning modules can also be used to provide clinical updates, “mandatory” education required in clinical agencies, or background material in preparation for higher-order application in a classroom or clinical setting. Modules are often integrated into classroom or online courses as reusable learning objects (RLOs), predeveloped content with objectives, content, and evaluation that can be used in courses as required or optional learning activities. It is increasingly common for RLOs to accompany textbooks as ancillary teaching materials; they are also available from web-based learning resource repositories such as MERLOT (http://merlot.org). Online courses can also be developed to integrate with face-to-face meetings in classrooms or clinical practice. These blended courses, also referred to as web-enhanced, web-supported, or hybrid courses, combine the benefits of face-to-face, classroom, or clinical experiences with the online learning community (Bonk & Graham, 2005). Here, the educator uses online assignments such as pretests or case studies to assess student knowledge and facilitate learning course concepts before students participate in face-to-face classroom activities. The educator may even decide to deliver a short online video or audio stream on selected course concepts prior to class. Students can receive feedback about their learning before they come to the classroom, and thus faculty and students are better prepared to use classroom time to clarify misunderstood concepts or focus on more complex problems such as those related to developing clinical decision-making skills. Blended courses can use a combination of technologies to meet the needs of students. For example, for those students who are enrolled in the course but live far away from the campus, one-way or two-way web-based video conferencing may be used to “connect” students to the class during the times of on-campus class meetings. The goal of blended learning is to take advantage of faculty expertise, the learning management toolkit, and just-in-time learning to provide learners with opportunities to learn and apply content, practice and receive feedback, think critically, and assume the role of the nurse across all domains of learning. The educator must make well-thought-out decisions as to which experiences should be held in the classroom and which should be held in the OLC. Table 23-1 offers suggestions for blending learning in classroom, clinical, and laboratory settings with an online learning environment. TABLE 23-1 Blending Online Teaching with Various Learning Environments It is also important to acknowledge that some of the most strategic marketing of online education may need to occur “internally” within the institution (Billings, 2002). Online education is still new to many faculty, students, and administrators. Faculty who are “early adopters” of technology and online education will need to communicate the potential advantages of online learning to faculty who are more skeptical. Institutions have reported that using benchmark standards helps ensure quality in online courses (Leners, Wilson, & Stizman, 2007; Little, 2009). To promote the development of quality online education courses and programs, quality indicators and benchmarks have been established by professional organizations and accrediting bodies for institutions to use when planning online programs and courses. Most states have established guidelines for the delivery of distance education through the government bodies that regulate higher education. Examples of frequently referenced quality indicators include those established by the Sloan Consortium (Moore, 2005) and the Institute for Higher Education Policy (2000). The quality indicators and benchmarks espoused by these two organizations are similar in nature in that they identify essential elements that must be addressed to ensure quality in online education: institutional support and commitment; effective course design and teaching–learning principles, faculty development, support, and satisfaction; student support and satisfaction; and outcome evaluation related to learning effectiveness. How each institution decides to address these elements will vary depending on the resources available to the institution and the specific needs of educators and learners. Reliable and effective technology support for faculty and students is essential for delivering quality online education. As mentioned previously, a decision will need to be made about which technology support services will be centralized within the institutional structure and which will be decentralized in the individual schools and programs. A combination of centralized and decentralized support may be a more effective support model. Outsourcing support services is another option to be considered, and may be more economically feasible depending on the extent of technology expertise that already exists within the institution. The level and extent of technology support that the institution will provide to faculty and students will also need to be determined (Halstead & Coudret, 2000). Many institutions have found it necessary to provide around-the-clock support services to faculty and students to limit undue frustration and “down time” related to technology issues. Faculty and student satisfaction with online learning is frequently related to their satisfaction with technology support services. The acquisition and maintenance of the hardware and software necessary to support online education and facilitate access is another area that must receive serious institutional attention. Is the institution’s current computer network system and bandwidth capable of providing online access to large numbers of simultaneous users with speed and reliability, or are upgrades required? Do faculty have convenient access to the hardware and software needed to support teaching online? Is there a plan to replace computer hardware and software on a regular schedule in faculty offices and student computer clusters to maintain access to adequate technology resources? Do students have access to broadband Internet services in their geographic region? If not, online courses will have to be developed with these bandwidth constraints in mind and content delivery options that require large amounts of bandwidth, such as video streaming, will need to be minimized or avoided (Richard, Mercer, & Bray, 2005). When implementation of online learning is initiated, faculty development needs will likely be focused on the following areas: instructional design and course development, technology management, workload and time management, role reconceptualization, student–faculty interactions, and assessment and evaluation of learner outcomes (Halstead & Coudret, 2000; Lahaie, 2007b). Before faculty begin any online course development, it is important to assess their knowledge and comfort level regarding conversion of traditional classroom courses into online courses and identify what level of instructional design support will be needed. Developing expertise in online teaching is usually a gradual learning process for faculty and initially may be intimidating even for experienced faculty (Zsohar & Smith, 2008). Faculty who are expert teachers in the classroom suddenly find themselves in the role of a novice when it comes to teaching online (Ryan, Hodson-Carlton, & Ali, 2004). Faculty will need to reconsider their role in the learning process and redesign their pedagogical strategies to facilitate student learning (Ali et al., 2005; Richard et al., 2005; Ryan, Hodson-Carlton, & Ali, 2005; Zsohar & Smith, 2008) and will benefit from mentoring during this adjustment. Scheduling an ongoing series of educational sessions focused on such topics as technology and time management, developing online courses that promote active learning and foster student–faculty interactions, and evaluating learner outcomes throughout the academic year can help faculty acquire the knowledge and skills necessary to successfully design and teach online courses. These topics are covered in more depth later in this chapter. Introducing online education into a program will have a major impact on the delivery of learner support services, especially if the introduction of online education affects more than just a few individual courses. All aspects of the institution’s student support services will ultimately be affected and need to be reconsidered to best serve the needs of students who are geographically distant from the campus, as well as those who are on campus (Mills, Fisher, & Stair, 2001; Nelson, 2007). It is a requirement of national higher education accrediting bodies, as well as nursing accrediting bodies, that the academic support services for online students be similar to those available for on-campus students (Baldwin & Burns, 2004). Student support that will need to be reconsidered and redesigned for students who enroll in online programs include academic advising, tutoring, financial aid, library, and bookstore services. Ensuring that all online experiences are accessible to students with disabilities is another important institutional consideration (Nelson, 2007). The admission and registration processes may also need to be restructured so that students who live at a distance will be able to accomplish these tasks without being physically present on campus. Faculty should proactively address the development needs of students engaging in online learning. Learners who are new to online learning frequently need some initial guidance in how to manage their time when they are taking online courses. The relatively independent nature of online education requires students to understand that they are assuming responsibility for their own learning to an extent with which they may be unaccustomed (Johnston, 2008). They are moving from the structure of the traditional classroom to a more unstructured learning environment that does not necessarily include the physical, face-to-face presence of faculty and peers and the weekly time commitment to attend class. Some students may assume that an online course will be “easier” than a traditional course, a notion that is usually quickly dismissed after the course begins and they become overwhelmed with the independence that an online course allows them in managing their own time to meet their learning needs. It is easy for students to underestimate the amount of self-direction and self-pacing that is needed to be successful in online learning. Faculty can help students by clearly identifying expectations for participation and due dates for assignments (Beitz & Snarponis, 2006; Zsohar & Smith, 2008). If weekly online discussion is expected, this should be stated in the course syllabus. During the first 2 to 3 weeks of the course, those students who are not participating in the course should be actively sought out. The lack of participation is likely due to technology issues or the inability to be self-directive in learning (Halstead & Coudret, 2000). Reaching out to the student at this critical point in the course may make a difference in whether the student will be successful in completing the course. Students will also require an orientation to the course management system and any other technology that they may be required to use in their coursework. Although orientation to technology can occur face to face or using printed materials, Carruth, Broussard, Waldemeirer, Gauthier, and Mixon (2010) developed a 5-day online orientation course for graduate students who lacked sufficient technological skills to be effective learners in their online course. Evaluations indicated that the students had improved technology proficiency and, because attrition for students who did not have the necessary technology skills was reduced, the course is now required. The institution needs to consider how it can provide orientation to technology for distant learners, as well as technology support when students encounter problems. In addition to an orientation to support services, students who enroll in online programs also need an orientation to the institution, school, and program. The institution needs to consider how best to establish relationships and “create a sense of presence” (Nelson, 2007, p. 188) with students who may attend the institution only from a distance yet will obtain a degree and become alumni. Effective use of websites, social networking, and virtual tours of the campus can help form connections that will lead to satisfactory student–institution relationships. Faculty and administrators also need to give consideration to how online courses and programs will be assessed and evaluated to determine whether curriculum and program outcomes are being met, as well as for the purpose of continuous quality improvement (Billings, 2000). Effectiveness of online courses and programs can be measured using a variety of methods. As mentioned previously, quality indicators and benchmarks, as well as accreditation standards, provide guidelines for measuring program quality. A systematic evaluation plan can be established that will foster continuous, ongoing quality improvement efforts in all aspects of program delivery: institutional support, faculty satisfaction, student satisfaction, adequacy of technology and student–faculty support services, and effectiveness in meeting expected learner outcomes, including a comparison to traditional course offerings. Data regarding student enrollment numbers, academic progression, and graduation can be compiled to address retention concerns. Data related to established program outcomes can be collected to demonstrate effectiveness of selected pedagogical strategies (Broome, Halstead, Pesut, Rawl, & Boland, 2011; Hunter & Krantz, 2010). Rubrics can also be established to assist faculty with their own and peer review of their online courses (Blood-Siegfried et al., 2008). The faculty member’s role as an educator undergoes a change when he or she is teaching online courses (Halstead, 2002). First of all, real-time, face-to-face interaction with students becomes more limited, with many interactions occurring asynchronously. Most important, in online courses the educator is less likely to be the primary source of information for students. Instead, the educator’s role becomes one of facilitating students’ learning experiences. Students assume more responsibility for identifying their own learning needs and being self-directed in how they choose to meet identified learning outcomes. For some faculty who are new to online teaching, this results in feeling a loss of control over the learning process. Teaching online may require faculty to rethink long-held beliefs about the role of the educator in the teaching–learning process and explore new paradigms of teaching (Shovein, Huston, Fox, & Damazo, 2005). Two common concerns of faculty who are engaged in online teaching for the first time are related to how to facilitate and manage asynchronous online discussion and how to manage time most effectively. Faculty have indicated that their workload increases when they engage in online teaching (Ryan et al., 2005). In their comparison of faculty workload in web-based and face-to-face graduate nursing courses, Anderson and Avery (2008) found that while the amount of faculty teaching time did not increase in a statistically significant manner in online courses, there were differences in the amount of time spent in course preparation and student contact time, with those faculty teaching online courses reporting more time devoted to each of these activities. More research is needed to more fully understand the demands on faculty workload created by online teaching. Time management frequently becomes an issue for faculty teaching online courses because of the amount of student communication generated within the course. The communication generated by students in online courses can be overwhelming if the educator has not given some prior thought to how to manage it. Successful management of asynchronous discussion requires the educator to initially identify the purpose of the discussion and to be sure that all students are contributing to the discussion (Halstead, 2002). As the online discussion unfolds, the educator may find it necessary at times to change the direction of the discussion or to correct any factual errors students may have made in their postings. However, faculty usually serve as discussion facilitators (Zsohar & Smith, 2008). It is not desirable to respond to every comment made by students in online discussion; faculty should strive to avoid dominating the conversation, reserving their comments to emphasize or summarize key concepts, praise students and provide feedback as appropriate, and make other similar contributions. Another means of managing online communication is to have students provide peer feedback to postings in the discussion forums. Students can critique posted assignments, lead and summarize group discussions, and participate in collaborative group learning activities. Students can be responsible for synthesizing and analyzing the responses in the forum, thus providing faculty and classmates from other groups an opportunity to respond to summarized work. Faculty can appoint and rotate student discussion leaders to provide opportunities for all students to experience a leadership role. Not only do these techniques foster timely feedback and reduce sole reliance on the faculty for feedback, but they also promote active learning (Phillips, 2005). These strategies also work to effectively manage discussion in classes that have larger enrollments.

Teaching and learning in online learning communities

Online learning communities

Classroom, Clinical, or Laboratory Learning Environments

Online Learning Environment

Demonstration of psychomotor skills and clinical decision-making skills with simulated or standardized patient scenarios

Discussion of difficult-to-learn content; clarification of assignments

Clinical practice (with or without preceptor or faculty)

Demonstration of verbal and nonverbal communication skills requiring interpretation and feedback; modeling of professional values and behaviors; evaluation of student presentation style and abilities

Panel discussions with guest speakers when online presentations are not feasible

Clinical practice situations requiring feedback to prevent or reverse an error

Active learning strategies designed to focus on fostering culture of safety and prevention of errors such as root cause analysis, case studies, debate, one-minute papers, and self-paced learning modules

Administration of high-stakes examinations and psychomotor skills competency validation

Self-evaluation activities; optional learning activities for testing or enhancing learning; remediation learning options

Institutional planning for online learning

Institutional planning and commitment

Faculty development and support

Learner development and support

Assessment and evaluation of online learning

Faculty role in online learning

Managing online discussion

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Teaching and learning in online learning communities

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access