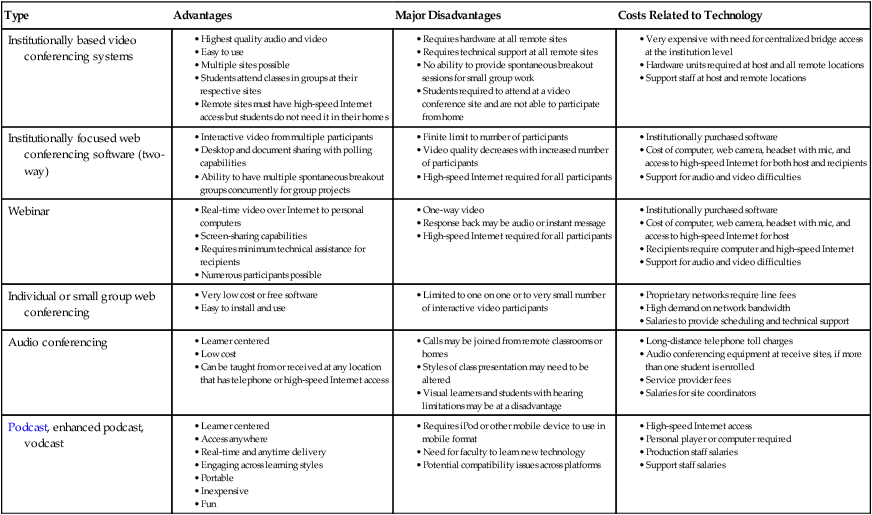

Technological advances in computers and broadband connectivity have opened up new ways for nursing faculty to connect with their students and deliver media-rich content at a distance. Increasingly, students want to learn in more flexible programs that maximize their time and other life commitments (Connors, 2008; Maring, Costello, & Plack, 2008). At the same time, higher education programs are recognizing the need to increase student access to distance-accessible programs (Allen & Seaman, 2007). Distance education offers the ability to bring practitioners to rural and underserved areas (Effken & Abbott, 2009). By educating those who already live in rural areas, there may be a greater likelihood that they will remain and practice in their home towns upon completion of their studies (Effken & Abbot, 2009). There is a current faculty shortage in nursing schools, and this trend is expected to worsen in the coming years with advancing faculty age and looming retirements (American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2010). Distance education programs offer a means to reduce the faculty shortage and connect specific student learning interests with faculty expertise, despite the distance between the two (Billings, 2010; Mancuso-Murphy, 2007). Distance education delivery systems that encourage innovation and flexibility have the potential for maximizing use of institutional infrastructure, improving access to credit courses, and providing consistency for learning at multiple locations. Online education is continuing to grow at a rate that is faster than the overall higher education market in general (Allen & Seaman, 2007). Numerous studies in distance education continue to support that learning at a distance is at the very least equivalent to traditional face-to-face courses, and in fact there are data to suggest that blended methods may produce the best outcomes overall (U.S. Department of Education, 2009; Zhao, Lei, Lai, & Tan, 2005). Blended, or hybrid, approaches use a combination of online and face-to-face formats. Synchronous video technologies offer a way to deliver blended courses to students at a distance, without requiring the time and expense associated with travel to the host site. The use of blended approaches in higher education is expected to increase in the coming years (Kim & Bonk, 2006). The technologies available today offer a wide variety in strategies for delivering blended approaches at a distance. Distance learning tends to capitalize on a constructivist, or problem solving, approach to learning. This approach is in direct contrast to Gagné and Briggs’s (1979) distinct learning groups, which are based on a hierarchy of complexity and the need for mentoring and role modeling. However, distance learning seems to support Piaget’s (2001) position that learning is not just inherent or just experiential in nature, but a combination of both. Driscoll (2004) identifies constructivism as becoming more popular with the increased interest in computers as an educational tool. Although other instructional media are not excluded from this consideration, computers and networked learning have had a huge impact on the learner’s ability to construct and manage his or her own learning environment. Distance learning and computer-based instruction have created a newfound independence. The variety of options available to support distance instruction continues to increase as technologies improve and the transformation from a teacher-centered focus to a learner-centered focus becomes more prominent (Billings, 2007; Connors, 2008). Use of distance learning technologies requires planning and development of materials long before the course begins (Connors, 2008). State-of-the-art resources for faculty development of instructional materials must be available. Training and support for faculty to develop and use the new technology must be present. In addition, support for students must be provided in the use of the technology. With proper resources for development and support, faculty can deliver distance-accessible programs that meet the educational needs of students enrolled in online courses. With the shift toward computer-based instruction, the number of courses offered exclusively in the form of face-to-face instruction is decreasing substantially. However, many courses offer a blended, or hybrid, approach with other technologies such as video conferencing, audio conferencing, video streaming, podcasting, and other specialized web-based computer applications. Some technologies use synchronous technologies, or technologies that connect people simultaneously, or at the same time. Other technologies use asynchronous approaches, allowing learners to access materials without the constraints of a specific time or place. This chapter covers selected strategies used in educating students who are geographically dispersed and separated from the main campus of instruction, and both synchronous and asynchronous approaches. An overview of delivery systems, their advantages and disadvantages, and other pertinent information specific to each medium are also presented in Table 22-1. TABLE 22-1 Instructional Delivery Systems A very high-fidelity version of institutionally based video conferencing is “telepresence.” Telepresence video conferencing uses a combination of life-size, high-definition video technology and special acoustic mics, speakers, and soundproofing to deliver an experience of near lifelike quality (Educause, 2009). Special attention is given to placement of embedded cameras at eye level, to give the illusion of being able to look the remote participants in the eye. Furniture is configured to match at each location, and the participant visually perceives the remote site as if they were looking across the table at a person in the same room. Currently, telepresence technologies are very expensive to install; however, as technology costs decrease over time, this type of technology may become a more viable and affordable option for more sites.

Teaching and learning at a distance

Type

Advantages

Major Disadvantages

Costs Related to Technology

Institutionally based video conferencing systems

Institutionally focused web conferencing software (two-way)

Webinar

Individual or small group web conferencing

Audio conferencing

Podcast, enhanced podcast, vodcast

Synchronous technologies

Institutionally based dedicated video conferencing systems

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Teaching and learning at a distance

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access