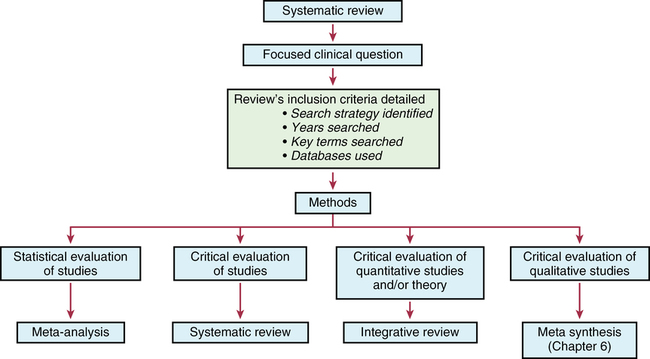

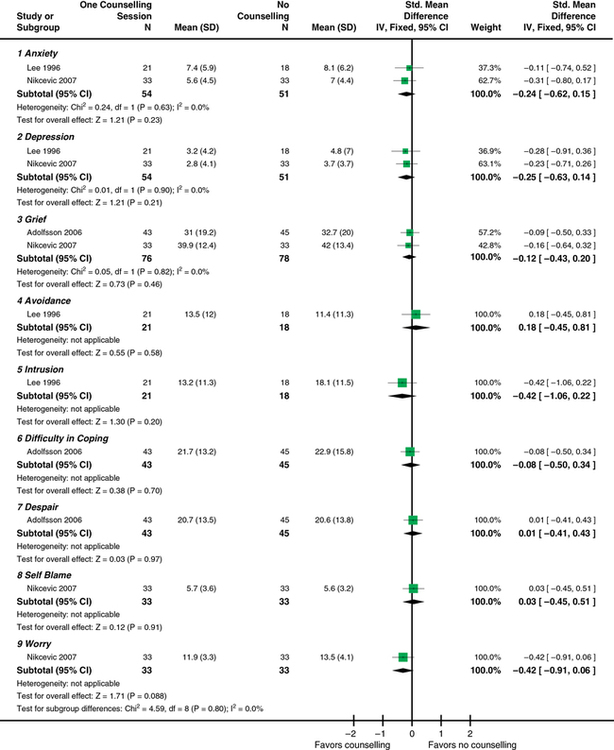

CHAPTER 11 After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following: • Describe the types of research reviews. • Describe the components of a systematic review. • Differentiate between a systematic review, meta-analysis, and integrative review. • Describe the purpose of clinical guidelines. • Differentiate between an expert and an evidence-based clinical guideline. • Critically appraise systematic reviews and clinical practice guidelines. Go to Evolve at http://evolve.elsevier.com/LoBiondo/ for review questions, critiquing exercises, and additional research articles for practice in reviewing and critiquing. The breadth and depth of clinical research has grown. As the number of research studies focused on similar content conducted by multiple researchers has grown, it has become important to have a means of organizing and assessing the quality, quantity, and consistency among the findings of a group of like studies. The previous chapters have introduced the types of qualitative and quantitative designs and how to critique these studies for quality and applicability to practice. The purpose of this chapter is to acquaint you with systematic reviews and clinical guidelines that assess multiple studies focused on the same clinical question, and how these reviews and guidelines can support evidence-based practice. Terminology used to define systematic reviews and clinical guidelines has changed as this area of research and literature assessment has grown. The definitions used in this textbook are consistent with the definitions from the Cochrane Collaboration and the PRISMA Group (Higgins & Green, 2011; Moher et al, 2009). Systematic reviews and clinical guidelines are critical and meaningful for the development of quality improvement practices. As defined in Chapter 1, a systematic review is a summation and assessment of research studies found in the literature based on a clearly focused question that uses systematic and explicit methods to identify, select, critically appraise, and analyze relevant data from the selected studies to summarize the findings in a focused area (Liberati et al., 2009; Moher et al., 2009). Statistical methods may or may not be used to analyze the studies reviewed. Multiple terms and methods are used to systematically review the literature, depending on the review’s purpose. See Box 11-1 for the components of a systematic review. At times, some of these terms are used interchangeably. The terms systematic review and meta-analysis are often used interchangeably or together. The only review type that can be labeled a meta-analysis is one that reviewed studies using statistical methods. An important concept to remember when reading a systematic review is how well the studies reviewed minimized bias or maintained the concept of control (see Chapters 8 and 9). You will also find reviews of an area of research or theory synthesis termed integrative reviews. Integrative reviews critically appraise the literature in an area but without a statistical analysis and are the broadest category of review (Whittemore, 2005; Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). Systematic and integrative reviews are not designs per se, but methods for searching, and integrating the literature related to a specific clinical issue. These methods take the results of many studies in a specific area; assesses the studies critically for reliability and validity (quality, quantity, and consistency) (see Chapters 1, 7, 17, and 18); and synthesize findings to inform practice. Meta-analysis provides Level I evidence; the highest level of evidence as it statistically analyzes and integrates the results of many studies. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses also grade the level of design or evidence of the studies reviewed (see Chapters 1 and 17). Of all the review types, a meta-analysis provides the strongest summary support because it summarizes studies using data analysis. The Critical Thinking Decision Path outlines the path for completing a systematic review. Once the studies in a systematic review are gathered from a comprehensive literature search (see Chapter 3), they are assessed for quality and synthesized according to quality or focus; then practice recommendations are made and presented in an article. More than one person independently evaluates the studies to be included or excluded in the review. Generally, the articles critically appraised are discussed in the article and presented in a table format within the article, which helps you to easily identify the specific studies gathered for the review and their quality. The most important principle to assess when reading a systematic review is how the author(s) of the review identified the studies to evaluate and how they systematically reviewed and appraised the literature that leads to the reviewers’ conclusions. The components of a systematic review are the same as a meta-analysis (see Box 11-1) except for the analysis of the studies. An example of a systematic review was completed by Fowles and colleagues (2012) on the effectiveness of maternal health promoting interventions. In this review, the authors • Synthesized the literature from studies on the effectiveness of interventions promoting maternal health in the first year after childbirth. • Included a clear clinical question; all of the sections of a systematic review were presented, except there was no statistical meta-analysis (combination of studies data) of the studies as a whole because the interventions and outcomes varied across the studies reviewed. Meta-analysis uses a rigorous process of summary and determining the impact of a number of studies rather than the impact derived from a single study alone (see Chapter 10). After the clinical question is identified and the search of the review of published and unpublished literature is completed, a meta-analysis is conducted in two phases: Phase I: The data are extracted (i.e., outcome data, sample sizes, and measures of variability from the identified studies). Phase II: The decision is made as to whether it is appropriate to calculate what is known as a pooled average result (effect) of the studies reviewed. Effect sizes are calculated using the difference in the average scores between the intervention and control groups from each study (Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews for Interventions, 2011). Each study is considered a unit of analysis. A meta-analysis takes the effect size (see Chapter 12) from each of the studies reviewed to obtain an estimate of the population (or the whole) to create a single effect size of all the studies. Thus the effect size is an estimate of how large of a difference there is between intervention and control groups in the summarized studies. For example, the meta-analysis in Appendix E studied the question “Does counseling follow-up of women who had a miscarriage improve psychological well-being?” (Murphy et al., 2012). The studies that assessed this question were reviewed and each weighted for its impact or effect on improving psychological well-being. This estimate helps health care providers decide which intervention, if any, was more useful for improving well-being after a miscarriage. Detailed components of a systematic review with or without meta-analysis (Moher et al., 2009) are listed in Box 11-1. In addition to calculating effect sizes, meta-analyses use multiple statistical methods to present and depict the data from studies reviewed (see Chapters 19 and 20). One of these methods is a forest plot, sometimes called a blobbogram. A forest plot graphically depicts the results of analyzing a number of studies. Figure 11-1 is an example of a forest plot from Murphy and colleagues (Cochrane Review, 2012; see Appendix E). This review identified whether follow-up by health care professionals or lay organizations at any time affects the psychological well-being of women following miscarriage.

Systematic reviews and clinical practice guidelines

Systematic review types

Systematic review

Meta-analysis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Systematic reviews and clinical practice guidelines

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access