The McColl et al. review examined studies testing most of the recommendations in Moser and Kalton and in Figure 19.1. Not surprisingly, given that most people would probably agree that these recommendations have a ‘common sense’ feel to them and intuitively seem very similar to how we would organise, for example, a conversation which sought to gain information from someone, most of them were supported.

However, the authors do note that a certain amount of caution should be applied, given that the majority of the studies into the relative merits of different ways of organising questionnaires were not conducted with health issues. Moreover, not all recommendations were supported. For example, it has been held that mixing negatively and positively worded questions reduces ‘response set’ (the tendency to tick consecutive questions with the same numbered response). Whist this might be so, there is an unwanted effect in reducing response validity, as accuracy of response is less for negatively worded items or mixed lists of positive and negative items. There is, therefore, potentially no advantage in mixing the polarity of items.

Likewise, the idea of grouping similar questions together makes intuitive sense, but is of doubtful value, because doing so creates context effects where responses to subsequent questions may be affected by responses to the preceding ones.

Finally, there is probably insufficient evidence upon which to base recommendations about the appearance of questionnaire materials, such as length, double- or single-sided printing, font size, nature and placement of instructions. In this context, it should be noted that this is because the amount of study given to these issues has been small, and absence of evidence of effect should not be taken as evidence of no effect. It is probably as well to offer participants well-presented questionnaires, even in the absence of consensus as to the importance of presentation.

Administration

Deciding how to administer your survey is a fundamental decision in survey research. There are essentially two alternatives: will the respondent be assisted in completing the instrument, or will they do so unaided. If you opt for assisted completion, you then have a choice between face-to-face interviews and telephone interviews. Most recently, there is also the option of internet-based assisted completion, which may be mediated by email access to an interviewer or via web-based context-specific material which offers more limited assistance (rather like an intelligent version of completion guidance notes). As with questionnaire construction, there have been advantages traditionally associated with one form of administration rather than another.

Response rates and representativeness. Assisted administration is usually associated with higher response rates, with less refusals, better access to a specific named individual and follow-up of that person. Finally, it is potentially more inclusive of people from different cultures or who have specific issues such as the inability to read.

Control of administration procedure. Assisted administration is usually claimed to give better control. For example, it deals best with long, complicated materials and allows the interviewer to explain difficulties with comprehension. It is also associated with lower non-response to individual items within a questionnaire.

By contrast, unaided response, typically via postal questionnaire is poor at all the above. However, it does have distinct advantages.

Interviewer bias. Postal questionnaires are regarded as being less open to the influence of the researcher. For example, there is no opportunity for the researcher to introduce bias either by way of the manner in which questions are asked or through providing more explanation (or different explanations) to some respondents than to others. One other important characteristic of the unaided interview is that the respondent is less likely to be influenced by social desirability considerations such as the desire to have the interviewer think well of them.

Practical constraints. Postal surveys have a huge advantage here for several reasons. There is no need to give staff special training (including possibly extensive training to reduce bias). The amount of staff time is small compared with either face-to-face or telephone interviews, and this again leads to cost reduction. If a suitable follow-up strategy can be designed, the amount of time taken to complete the survey can be comparatively modest, and large numbers of people can be reached during this small time period. This can lead to greater representativeness if issues of sampling bias can be overcome. Moreover, large samples usually suitable for more advanced statistical treatments.

However, despite the seemingly obvious nature of these supposed advantages and disadvantages, not all are supported by research evidence. The McColl et al. review found that evidence for some of the distinctions between assisted and unaided survey completion was equivocal. Their overall recommendation was that decisions regarding administration should be made on a survey-by-survey basis, taking account of study population, topic, sampling approach, volume and complexity of data to be collected, and resources available. No single approach to survey administration consistently outperforms another.

Thus, when face-to-face surveys, telephone surveys and postal questionnaires are compared, there is usually a higher response rate to face-to-face and telephone, but no consensus on whether face-to-face has higher response rate than telephone. Likewise, there is no unequivocal evidence that postal interviews are better than face-to-face at dealing with sensitive issues or social acceptability responses.

Enhancing response rate

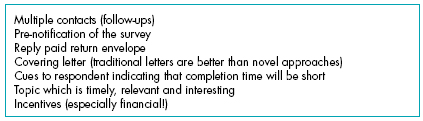

We have already noted that face-to-face and telephone interviews are generally associated with higher response rates than postal surveys. However, there are a number of other things you can do to increase response rate which have been supported by research evidence, and some of these are very simple to achieve. They are summarised in Figure 19.2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree