Surgical Supplies and Instruments

Learning Objectives

1. Define, spell, and pronounce the terms listed in the vocabulary.

2. Apply critical thinking skills in performing the patient assessment and patient care.

3. Describe typical solutions and medications used in minor surgical procedures.

4. Summarize methods for identifying surgical instruments used in minor office surgery.

5. Outline the general classifications of surgical instruments.

6. Identify surgical instruments.

7. Describe the care of surgical instruments.

8. Identify types of sutures and surgical needles.

9. Explain the medical assistant’s responsibility to help ease patients’ concerns about procedures.

Vocabulary

cannula (kan′-yoo-lah) A rigid tube that surrounds a blunt trocar or a sharp, pointed trocar inserted into the body; when withdrawn, fluid may escape from the body through the cannula, depending on where it was inserted.

curettage (kyur′-eh-tahjz) The act of scraping a body cavity with a surgical instrument, such as a curette.

dilation The opening or widening of the circumference of a body orifice with a dilating instrument.

dissect To cut or separate tissue with a cutting instrument or scissors.

fascia A sheet or band of fibrous tissue deep in the skin that covers muscles and body organs.

patency Open condition of a body cavity or canal.

Scenario

Tom Anderson, CMA (AAMA), works for Dr. Sheila Samanski, a dermatologist who frequently performs minor surgical procedures in the office. Tom assists Dr. Samanski with procedures and is also responsible for maintaining stock supplies in the minor surgery room, including solutions and medications, and for cleaning, maintaining, and inspecting the surgical instruments. Because there are no procedures scheduled for today, Tom is planning to compile an inventory of supplies and equipment and perform routine maintenance activities.

While studying this chapter, think about the following questions:

• What solutions and medications should be available in the surgical area of a medical office?

• What are the typical instruments used in minor surgical procedures?

• How are surgical instruments identified and classified?

• What types of sutures and needles are used in minor surgical procedures?

Office surgery is restricted to the management of minor problems and injuries. The medical assistant is expected to prepare the patient and the sterile field, assist the physician as needed, take care of the patient after the procedure, properly disinfect the area, and document appropriately. Some medical assistants are employed in outpatient surgical facilities and are expected to assist with procedures that once were performed in the hospital. Although these more difficult operations may involve complete gowning and gloving with surgical masks and caps, the two surgical chapters in this text limit discussion and descriptions to the routines necessary to prepare for and assist in minor surgery only. This chapter includes a discussion of surgical supplies and instruments, the care and handling of instruments, and the different types of surgical sutures and needles. It prepares you for Chapter 57, which presents sterilization, preparation of the sterile field, specific minor surgical procedures, and care of the patient.

Minor Surgery Room

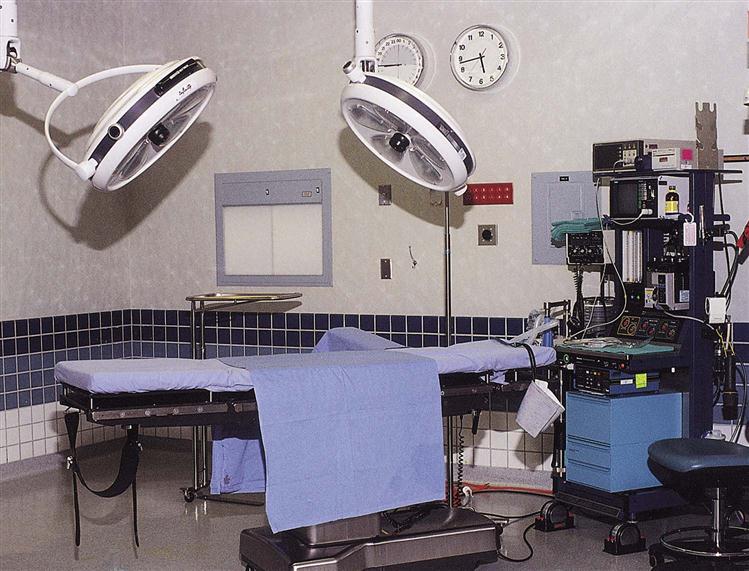

When minor surgery is routinely performed, the medical office is designed to include a changing room and a minor surgery room that are separate from the other examining rooms. Larger surgery centers have recovery rooms and family waiting areas. The minor surgery room in the physician’s office setting should be near a workroom with a sink and an autoclave if the room does not have its own. It should be easy to disinfect and uncluttered to allow easy movement and minimal dust collection. In addition to the operating table, equipment should include a clock with a second hand, an operating light, sitting stools, and Mayo stands (Figure 56-1). Cabinets with countertops are necessary to serve as a side or back table during the surgery. All surgical supplies are stored in these cabinets. Supplies used in this room should not be used elsewhere, and supplies used elsewhere should not be brought into this room.

Surgical Solutions and Medications

Treatment room supplies include standard solutions and medications that are used in minor surgery and dressing changes. Although the solutions and medications listed here are basic, every physician’s office practice has preferred items and methods of applying them. The medical assistant is responsible for their care and for maintaining up-to-date supplies.

Sterile water is kept in two forms. Multiple-dose vials are used as a diluent for medications; larger containers of sterile water are for rinsing instruments that have been in a chemical disinfectant solution.

Sterile physiologic saline solution (0.9%) is also stocked in two sizes. The small multiple-dose vial is used for injection. A larger container of sterile saline is used for rinsing and irrigating wounds. These commercially prepared products are ordered from a medical supply company.

The surgical site on the patient must be prepared preoperatively with an antiseptic skin cleansing preparation to reduce the number of pathogens. Although it is not possible to remove all microorganisms from the skin, it is important to prepare the surgical site to remove transient and pathogenic microorganisms on the skin’s surface and to reduce resident flora. In addition, the surgeon’s hands and those of the medical assistant require disinfection to reduce the chances of wound contamination even though hands will be covered with sterile gloves. Surgical scrub preparations should have a broad antimicrobial action effective against bacterial spores; they also should work rapidly to reduce transient bacteria, show evidence of persistent activity on the skin, and work despite the presence of organic matter such as blood or wound drainage. Research indicates that chlorhexidine (Hibiscrub or Hibiclens) and povidone-iodine (Betadine) are safe and effective antiseptics.

Even minor surgical procedures require the use of anesthetics, which either are injected locally at the site of the procedure or may be sprayed on the skin as a preinjection anesthetic. For patients who find injections of local anesthesia painful or traumatic, the physician may first spray the injection area with a topical anesthetic, such as Fluori-Methane 15%, which is supplied in 3.5-ounce amber glass bottles for either fine or medium spray. Immediately after spraying the site, the physician makes a series of injections around the area with a local anesthetic.

Another topical anesthetic spray is ethyl chloride, a vapocoolant that controls pain associated with minor surgical procedures, such as lancing boils or incision and drainage of small abscesses, by causing localized freezing of the affected area. Because ethyl chloride is highly flammable, it should never be used in the presence of electrical cauterizing equipment, and it requires the application of petroleum jelly to surrounding areas to protect them from the cooling action of the spray. It has a short duration, so all equipment must be prepared and the physician must be ready to perform the procedure before it is applied.

Local anesthetics are injected into the subcutaneous tissue. These produce a temporary cessation of feeling at the site of injection by blocking the generation and conduction of nerve impulses. Many different types of local anesthetics are available, but all share the same suffix, -caine. Those used most frequently include lidocaine (Xylocaine), chloroprocaine (Nesacaine), and bupivacaine (Sensorcaine). Local anesthetics are purchased in multiple-dose vials of 30 to 50 mL and in varying strengths, such as 0.5%, 1%, and 2%. They begin acting relatively quickly, within 5 to 15 minutes; the duration of action depends on the type of anesthetic, but they usually last 1 to 3 hours. When highly vascular areas are involved, local anesthetics containing epinephrine may be used. Epinephrine causes vasoconstriction at the site, which keeps the anesthetic in the tissues longer, prolonging its effect. It also minimizes local bleeding. However, epinephrine is not used in areas where decreased circulation may cause problems with healing, such as fingertips or toes.

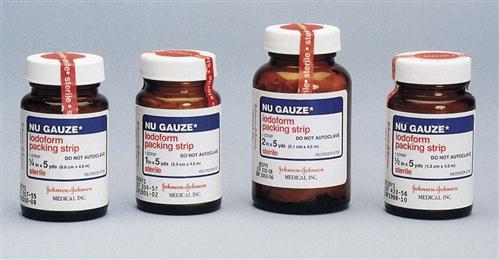

All tissues removed, or biopsied, from the patient are sent to the pathology laboratory for analysis. A 10% formalin solution typically is used to preserve excised tissue for specimens. Specimen bottles are purchased with preservatives included and should be part of the supplies prepared for a surgical procedure if a biopsy is to be done. The physician places the specimen in the container, and the medical assistant is responsible for accurately labeling the container with the patient’s name, the date of collection, and the type of specimen.

Sometimes the physician may want to use topical silver nitrate (AgNO3) solution or coated applicator sticks to stop localized bleeding, such as with epistaxis (nosebleed) or capillary bleeding at the site of a wound. The applicators must be kept in lightproof brown containers, and the most commonly used strength is 20%. The applicator sticks are convenient for use in the mouth or nose.

Surgical Instruments

The medical assistant must know which instruments are used for each procedure and should be able to identify and understand the function of the surgical instruments preferred by the physician. Instruments have clearly identifiable parts and can be visually differentiated from one another (Procedure 56-1). The basic components are the handle, the closing mechanism, and the part that comes in contact with the patient, commonly called the jaws. Many instruments can be ordered with either straight or curved tips, depending on the operator’s preference and the task to be performed.

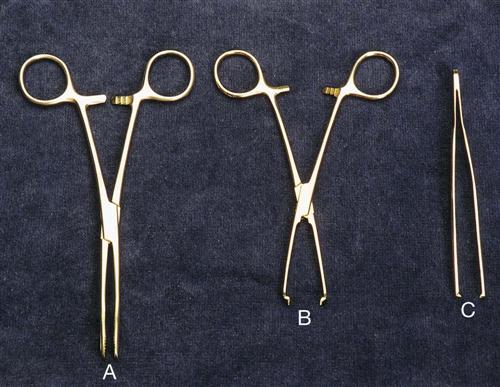

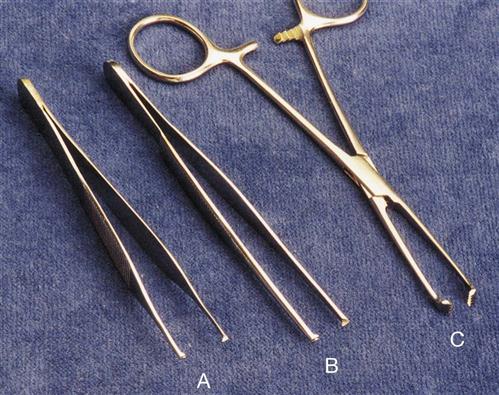

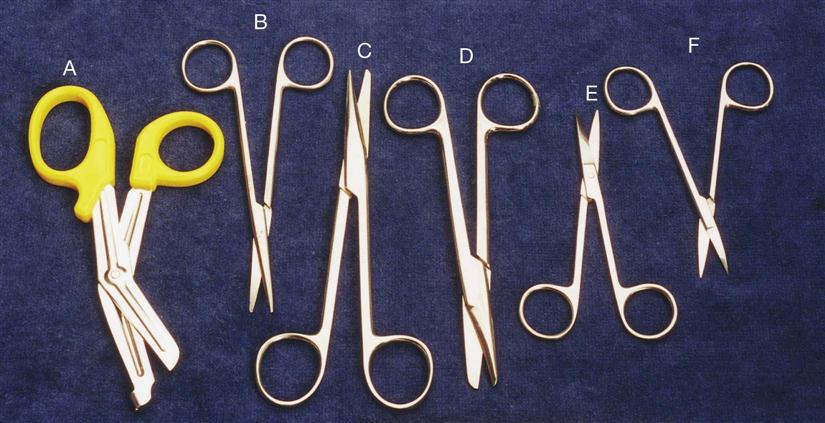

Instruments have either ring handles (finger rings; Figure 56-3, A and B) or spring handles (Figure 56-3, C; these sometimes are called thumb-handled or thumb grasp instruments). Scissors are an example of a ring-handled instrument; tweezers have spring handles. Some instruments have a hinge type of mechanism called a box lock.

Ratchets resemble gears and are located just below the ring handle (see Figure 56-3, A and B). They are used to lock an instrument into position. Most ratchets can be closed at three or more positions, depending on the thickness of the tissue or materials being grasped.

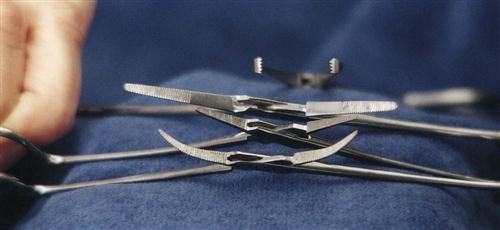

The inner surfaces of the jaws on some instruments have ridged teeth called serrations, and both ring-handled and thumb-type instruments may have them. These serrations may be crisscross, horizontal, or lengthwise (Figure 56-4). Serrations prevent small blood vessels and tissue from slipping out of the jaws of the instrument.

Instrument tips or jaws may be plain tipped or mouse toothed (Figure 56-5, A). If the tooth is large, the tip is called rat toothed (Figure 56-5, B). Tissue forceps usually are toothed instruments and are identified by the number of intermeshing teeth (e.g., 12, 23, 34). Allis forceps (Figure 56-5, C) are used to grasp delicate, soft tissues, so the teeth are finer, shallower, and more rounded. Other forceps have teeth that are sharper and deeper. Still others have sharp, hooklike, single or double teeth, such as a tenaculum or vulsellum. Usually, the tenaculum has a single, sharp hook on each jaw. The vulsellum has a double hook that resembles the fangs of a snake (see Figure 56-18, F). Toothed instruments commonly have ratchets for locking into towels or human tissues. Instrument tips may also be either straight or curved, depending on their use.

An instrument is usually named for its use (e.g., splinter forceps, for removing splinters) or after the person or people who developed it (e.g., Mayo-Hegar needle holder). Many general instruments are identified by the part of the body on which they are used (e.g., rectal speculum and nasal speculum).

There are thousands of surgical instruments with multiple name variations. The same instrument may have two or three different names, depending on the physician identifying it or the part of the country in which the practice is located. A physician may ask for a clamp or forceps when a Kelly hemostat is wanted. It is important to learn the physician’s preference in terminology. Learn to recognize the distinctive parts of instruments and the reasons for each part, and you will quickly build a working knowledge of hundreds of instruments.

Classifications of Surgical Instruments

Surgical instruments generally are classified according to their use, and most belong to one of four groups:

Cutting and Dissecting Instruments

Cutting and dissecting instruments, which are used for cutting, incising, scraping, punching, and puncturing, include scissors, scalpels, chisels, elevators, curettes, punches, drills, and needles. Instruments with a sharp blade or surface can cut, scrape, or dissect.

Bandage Scissors (Figure 56-6, A)

Operating (Surgical) Scissors

Metzenbaum (Metz) Scissors (Figure 56-6, B)

Mayo Scissors (Figure 56-6, C and D)

Iris Scissors (Figure 56-6, E and F)

Littauer Stitch or Suture Scissors (Figure 56-7)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree