CHAPTER 12 Supporting independent function and preventing falls

FRAMEWORK

This chapter addresses the challenge of falls and maintaining independent function in older people. The incidence of falls increases with age and the costs both in economic terms and in terms of personal disability are considerable. The authors give a comprehensive overview of the contributory factors, impact, value of screening, and best practice for prevention of falls and functional decline. They also address the challenges of implementing a successful program to minimise risk of falls and functional decline based on assessment and prevention strategies. Physical activity can assist in the prevention of falls and so must be encouraged in older people. [RN, SG]

Introduction

Functional decline is defined as ‘the reduced ability to perform tasks of everyday living, for example, walking or dressing, due to a decrement in physical and/or cognitive functioning’ (Clinical Epidemiology & Health Services Evaluation Unit — Melbourne Health 2004). The term ‘functional decline’ is used throughout this chapter to encompass changes in the ability to perform these functions. This chapter explores the relationships between functional decline, independence and falls in detail, reviews factors contributing to risk of functional decline and falls, and describes approaches to maximise function and independence and reduce risk of falls.

There are many definitions used to define a fall. It is important to ensure a common definition and understanding when discussing a fall with a client. For the purposes of this chapter, a fall is ‘an event that results in a person coming to rest inadvertently on the ground or floor or other lower level, excluding intentional change in position to rest on furniture, wall or other objects.’ (Yoshida 2007).

Incidence, contributory factors and impact of falls

The incidence of falls increases with age and varies according to residential location. Approximately 30% of older people living in the community fall each year and this increases to over 50% for those older than 90 (Fleming et al 2008; Gill et al 2005; Lord et al 1993; Talbot et al 2005). Falls are more common in frail older people living in residential aged care facilities (RACFs), where 30 to 60% of residents have been reported to fall each 12 months (Aronow & Ahn 1997; Jensen et al 2002a), and up to 80% in dementia specific units (van Dijk et al 1993). In hospitals, rates of falls have varied from 2.7 falls per 1000 bed days to more than 17 falls per 1000 bed days (Halfon et al 2001; Hanger 1999; Morse 2002). However, in each setting, these rates may well underestimate the true incidence of falls in all settings because of under-reporting of falls events. Falls may not be reported for a variety of reasons including:

Falls are a major cause of morbidity and mortality for older people. Five to ten percent of falls in community-dwelling older people result in major injuries (fractures, head trauma and major lacerations), while this rate increases to 10–30% in RACFs. An injury from a fall can be associated with subsequent functional decline (Russell et al 2006) and fear of falling, the latter occurring in up to 50% of older people following a fall. Falls have also been identified as a contributory factor in 40% of residential care admissions (Tinetti & Williams 1997). Further highlighting the dramatic impact of falls, one study found that 80% of older women preferred death to a ‘bad’ hip fracture that would result in going to a nursing home (Salkeld et al 2000).

Many risk factors for falls have been identified. In most older people who fall, more than one risk factor contributes to the risk of falls, and the risk increases with presence of more chronic health problems (Lord et al 2007). Risk factors are often divided into three groups:

Table 12.1 lists commonly reported risk factors for falls (Lord et al 2007). Many of these factors are also risk factors for functional decline (Dunlop et al 2005).

Table 12.1 Risk factors for falls and functional decline

| RISK FACTOR | FOR FALLS | FOR FUNCTIONAL DECLINE |

|---|---|---|

| Past history of a fall | ✓ | ✓ |

| Age | ✓ | ✓ |

| Female gender | ✓ | ✓ |

| Lower extremity weakness | ✓ | ✓ |

| Balance problems | ✓ | ✓ |

| Low levels of physical activity | ✓ | ✓ |

| Cognitive impairment | ✓ | ✓ |

| Psychotropic drug use and/or polypharmacy | ✓ | ✓ |

| Chronic medical problems such as arthritis, stroke or Parkinson’s disease | ✓ | ✓ |

| Sensory loss, including vision and somatosensory loss | ✓ | ✓ |

| Orthostatic hypotension | ✓ | |

| Acute health problem such as pneumonia, urinary tract infection | ✓ | |

| Dizziness | ✓ | |

| Diabetes | ✓ | |

| Depression | ✓ | ✓ |

| Incontinence | ✓ | ✓ |

Incidence, contributory factors and impact of low levels of physical activity and functional decline

Low level of physical activity is responsible for about 7% of the burden of preventable health problems and disability, and between 1.5–3% of total direct health care expenditure (Mathers et al 1999; Oldridge 2008). Physical inactivity is a risk factor for a range of health problems and functional limitations, including increased risk of falls (Lord et al 2007) and increased risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke, diabetes and some forms of cancer (Warburton et al 2007). Less than 50% of older people are sufficiently active to achieve health benefits (defined as up to 30 minutes per day of moderate or vigorous activity on most days of the week, or an accumulation of 150 minutes per week), with physical activity rates higher in older men than older women (Armstrong et al 2000; Bauman et al 2003). Therefore strategies to improve older people’s participation in physical activity have the potential to achieve a range of health benefits.

Moderate or vigorous intensity physical activities are required to achieve improved health outcomes (Glasgow et al 2005).

There are many approaches to organised physical activity. These include:

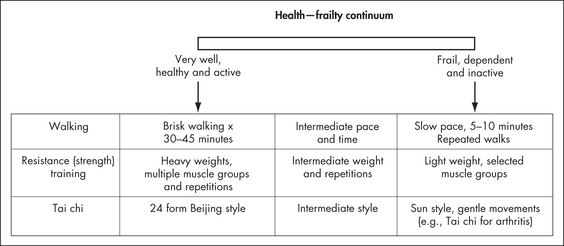

A specific type and intensity of physical activity will be of different challenge to older individuals depending upon their current level of fitness and their concurrent health problems. As such, a regular game of lawn bowls or bocci might have limited effect on health for a well older person (who would probably require a more physically taxing activity to achieve health benefits), however might be suitable and have some health-promoting effects for some less well older people. For a frail older person with multiple comorbidities however, this activity level might not be possible (see Fig 12.1).

Even frailer older people who have a range of acute or chronic health problems can still be involved in physical activity programs and derive positive health outcomes. For example, older people with stroke (van Peppen et al 2004), arthritis (Keysor & Jette 2001), Parkinson’s disease (de Goede et al 2001) and those with increased risk of falls (Sherrington et al 2004) have been shown to safely and effectively participate in physical activity programs. However, people with these health conditions should discuss commencing participation in a new form of physical activity with their general practitioner or other health professional, and it is often preferable for these people to commence an exercise program under supervision of a trained exercise leader such as a physiotherapist, accredited exercise leader or exercise physiologist (Nelson et al 2007).

There are many associated benefits of participating in physical activity in group settings. The social interactions and networking that occur during exercise groups have been highlighted as key factors influencing longer-term participation (Vrantsidis et al in press). However, some older people prefer to undertake physical activity alone. Many of the approaches to exercise described above (e.g., strengthening exercises, balance exercises, walking programs, tai chi) can be performed at home alone, sometimes with intermittent support (e.g., DVD of the tai chi movements), particularly after initial training with an exercise leader. Individualised exercise programs targeting balance and muscle strength problems might also be recommended as a home program. These are often prescribed after a comprehensive musculoskeletal assessment by a health professional, such as a physiotherapist. Home exercise programs incorporating balance and strengthening exercises have been shown to be effective in improving balance and muscle strength and reducing falls (Robertson et al 2002). Both group exercise programs and individualised home exercise programs have been shown to achieve positive health outcomes. Personal preference, safety issues, comorbidities and the desired health outcomes are important considerations in determining the type, location and intensity of an exercise program for an individual.

Age alone is not a barrier to participation in any form of physical activity. The number of concurrent health problems is a much stronger determinant of the type and level of physical activity an older person can undertake safely. Some well older people can continue to participate in quite vigorous physical activity (Nelson et al 2007) such as long-distance running or swimming.

Indicators (observational cues, without assessment) of functional decline and falls risk

VIGNETTE 1: Mary Johnson (Part 1)

Referring to Table 12.1, these changes suggest possible reduced balance (need for the walking stick), reduced leg muscle strength (difficulty standing up from a chair), reduced activity level and possible loss of confidence (not walking to shops any more).

Table 12.2 describes many of the indicators of modifiable risk factors for falls and functional decline (including low level of physical activity) and some cues that might indicate that the person is at increased risk and would benefit from assessment by a health professional assessment and a management program.

Table 12.2 Indicators of modifiable risk factors for falls or functional decline

| RISK FACTOR | OBSERVATION, CUE OR INDICATOR∗ |

|---|---|

| Past history of a fall | Observation of bruising or other injuries, apparent loss of confidence, direct questioning about falls. |

| Lower extremity weakness | Effort associated with standing up from a chair, needing to push up when standing up. |

| Balance problems | Unsteady or veering during transfers or walking, experiencing near falls, ‘furniture walking’, unsteady or overbalancing during reaching, bending or turning. |

| Low levels of physical activity | Obtain history of activities performed 12 months ago, compare to current activity level. Recent changes in activity level. |

| Psychotropic drug use / polypharmacy | Unsteadiness developing soon after commencing new medications, falls at night, presence of symptoms that might be side effects of some medications (e.g., dizziness, low blood pressure when standing up). |

| Chronic medical problems such as arthritis, stroke or Parkinson’s disease | Check medical history. |

| Sensory loss, including vision and somatosensory loss | Vision — inability to see detail, spilling drinks, bumping into objects, tripping, not wanting (or inability) to read or watch television. Somatosensory — poor skin condition, cuts or scratches on feet, lack of feeling in the feet. |

| Orthostatic hypotension | Light headedness or unsteadiness when sitting up from lying, or standing up from sitting or lying. |

| Acute health problem such as pneumonia, urinary tract infection | Sudden change in health status. |

| Dizziness | Spinning sensation, especially when turning quickly, can be associated with nausea and vomiting. |

| Diabetes | Weight loss, excessive urination, excessive thirst, fatigue, vision problems. |

| Depression | Lethargy, loss of appetite, loss of interest in activities, difficulty concentrating on tasks. |

| Incontinence | Frequent need for toileting, poor fluid intake, urinary or bowel accidents, nocturia, strong odour of urine. |

∗ from the Victorian Quality Council (Hill et al 2004). Website: www.health.vic.gov.au/qualitycouncil/downloads/falls/reference.pdf

Screening and assessment for activity level and falls risk

When there are indicators of potential risk factors for functional decline or risk of falls (such as those described in Table 12.2), there is then a need to determine the extent and causes of the risk factors. This will usually involve either a screening or assessment procedure. Screening or assessment can help to confirm presence of risk factors for falls or functional decline, and provide a framework for developing an individualised management or prevention program.

Screening and assessment for low levels of physical activity / functional decline

A widely recommended level of physical activity to maintain health is the accumulation of 150 minutes per week of moderate intensity physical activity, comprising 30 minutes on most days of the week (Armstrong et al 2000). Therefore, ascertaining the amount of physical activity over a 1 week period is a simple screen that indicates if a person is meeting this minimum requirement. Pedometers, accelerometers and actigraphs can also provide quantitative information on standing and walking or running-related activities.

For a detailed profile of physical activity either to assist with identifying specific areas of need, or to use in tailoring a physical activity program, more detailed physical activity assessments are required (Melanson & Freedson 1996). Examples of physical activity questionnaires include the 94 item Human Activity Profile (Fix & Daughton 1988) and the CHAMPS tool (Cyarto et al 2006). A new assessment tool that provides a measure of function, mobility, and balance performance is the de Morton Mobility Index (DEMMI). This tool has recently been shown to be a useful assessment of function in older people in hospital (de Morton et al in press).

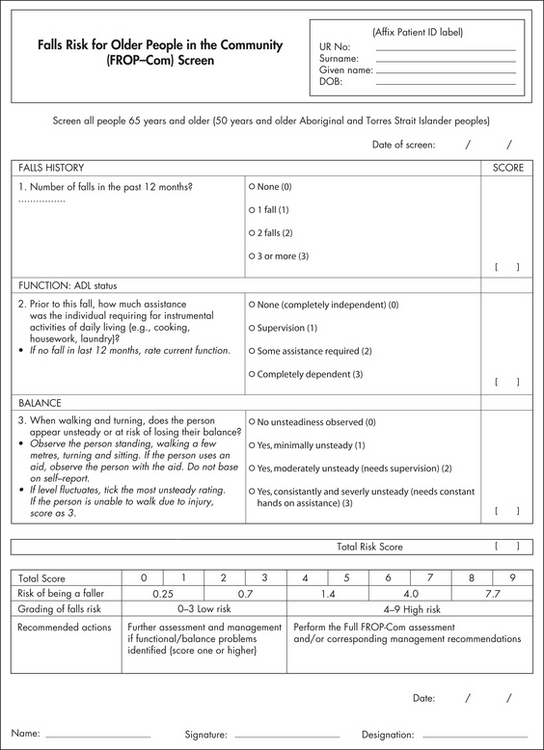

Screening and assessment for falls risk

An example of a falls risk screening tool (the FROP-Com screen) is shown in Figure 12.2 (Russell et al in press). This is a three-item screen for older people living in the community that was developed from a validated falls risk assessment tool (the Falls Risk for Older People — Community version: FROP-Com), shown in Figure 12.3 (Russell et al 2008). The FROP-Com screen has been used in a range of community-based settings, including older people with low falls risk (Murray et al 2005) and high falls risk (Russell et al 2006). Other assessment tools have been reported for use in residential care settings (Lundin-Olsson et al 2003) and in hospital settings (Haines et al 2007). The presence of fear of falling should also be considered for those at risk of falls, or who have had a recent fall. A screening question may be just to ask: ‘As a result of the fall or near fall, have you lost confidence in walking and other activities?’ For those who report positively, a detailed assessment of fear of falling (also called falls efficacy) should be undertaken. The Short Falls Efficacy Scale International (Short FESI) is a recently developed abbreviated assessment tool to measure fear of falling (Kempen et al 2008).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

It is important to ensure a common definition and understanding when discussing a fall with a client.

It is important to ensure a common definition and understanding when discussing a fall with a client. Falls are a major cause of morbidity and mortality for older people.

Falls are a major cause of morbidity and mortality for older people. Strategies to improve older people’s participation in physical activity have the potential to achieve a range of health benefits.

Strategies to improve older people’s participation in physical activity have the potential to achieve a range of health benefits.

Even frailer older people who have a range of acute or chronic health problems can still be involved in physical activity programs and derive positive health outcomes.

Even frailer older people who have a range of acute or chronic health problems can still be involved in physical activity programs and derive positive health outcomes. One of the strongest risk factors for having a future fall, and for functional decline, is having had a previous fall.

One of the strongest risk factors for having a future fall, and for functional decline, is having had a previous fall.