CHAPTER 3 Health care in a longevity regime

FRAMEWORK

This chapter raises the issue of longevity and the subsequent costs and quality of life that centenarians enjoy in Australia. McCormack has undertaken studies on the ‘old-old’ sector of the population and discusses the need for improved data on this sector to enable health care services to be oriented toward the needs of this special group. The data indicate that hospitalisation of this group is far less than expected and that over 94 years of age the rate of admission declines. Reasons are offered for why this phenomenon may occur but further study needs to be done to ascertain the factors involved. Interestingly, the centenarians in the study were reasonably contented with their lives and were not overly frail. The emergence of the ‘fifth age’ is upon society now and is likely to become more widely recognised as longevity continues to improve. [RN, SG]

Introduction

Peggy Ashburn turns 80 this year and says her friends are sometimes shocked when she tells them she is about to take her father, Jack Ross (aged 109 years), out for a meal. She told this author, who keeps the list of the oldest age-validated Australians, that she thinks people are surprised for a number of reasons. Firstly, that at her own advanced age she still has a living parent; secondly, that her father has lived such a long life; and thirdly, being an enlisted veteran of both world wars, that he has survived the trauma of war and lived on for such a long time. Mr Ross lived at home until five years ago and then entered residential care after a fall, but he remains relatively active and interested in the world around him. He is, of course, a national treasure because he is one of the few remaining World War I veterans in the world. However, Mr Ross’ story is not unique.

When French woman Jeanne Calment died in August 1997 aged 122 years and 5 months, she had achieved the remarkable feat of extending the human lifespan. Previously, the maximum life potential (i.e., the verifiable age at death of the longest-lived member of the species) was thought to be biologically limited to 120 years (Moody 1998). This ultimate limit to length of life has itself had a durable longevity until the unique Ms Calment challenged its intractability. Similarly in Australia, Christina Cock, who died in 2002 aged 114, was most likely the oldest ever woman (and oldest person ever) in Australia. At the time of her death, she was the third oldest age-validated person alive in the world.

There is no doubt that these people have lived to an extraordinary age — validated ages never before observed or experienced in human civilisation. In addition to this group of people, however, is another almost equally exceptional group. This is the growing number of people reaching the milestone of 100 years of age. Japan exceeded 28 000 centenarians by the year 2006 (up from 5000 in 1994), and one USA estimate is 72 000 plus in the early decades of the 21st century (Administration on Aging 1996; Medserve 1998). Further, the United Nations (UN) predicts there will be over 2 million centenarians alive in 2050 with very large numbers of centenarians in China and India (UN 2006).

In recognition of the importance of this new extreme ageing phenomenon which is redefining ‘old age’, there is an increasing number of centenarian studies underway, looking predominantly at the biomedical aspects of extreme ageing in terms of how and why more people are reaching this very old age. Only a few studies, such as The Georgia Centenarian Study (Poon 1992), The New England Centenarian Study (Perls et al 1999) and The Berlin Aging Study (Baltes & Smith 1999) have included the psychosocial aspects of survivorship. All these latter studies have used multidisciplinary teams for comprehensive assessment of centenarians. None, however, take this forward to the next step of intervention approaches. While it is essential that we understand why so many more people are reaching very old age, we also need to know the quality of their life at this milestone age. Does this demographic transition add life to years or just years to life? Also, we need to start understanding what the health care implications of this new longevity regime might be, and how we might prepare for it. No one researcher or country has fully clarified the impact of this new ageing phenomenon to date.

In Australia, very little work has been undertaken on this group (McCormack 2000, 2002). There are many publications on ‘the aged’ (i.e., those aged 65 years or more) but these works often present findings at such a highly aggregated age level that it can be difficult to detect differences within the group. Similarly, while we know that it is the ageing of the oldest old who will increase at the fastest rate (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS] 2003), and that this group may be more vulnerable to the exigencies of time (Baltes & Smith 2002), there is no specific social or financial estimates of the impact of, or on, the very old that have been developed in Australia. Vaupel and Oeppen (2002) estimate that females born today in low mortality/high longevity countries such as France and Japan already have a 50% chance of living to 100 years. Australia is also in that group of high-longevity countries (see below). Recent estimates claim the official population projections underestimate our future aged population, and this can be clearly seen among the oldest old, where, for example, the number of females aged 95–99 years will increase over the next 25 years by a factor of 5.8 compared to a factor of 2.0 for females aged 65–69 years (Booth 2003). These demographic imperatives emphasise the importance of us knowing and understanding the health and welfare implications of increasing longevity, especially with this growing group of remarkable people who survive to very old age.

This chapter thus presents some preliminary descriptive findings for Australia on what Beard (1991) called this ‘new’ generation of people aged around 100 years and older. The chapter firstly draws on historical census data to illustrate the emergence of centenarians in Australia, and then highlights some of the technical difficulties associated with actually identifying centenarians. After that, the chapter reports on their socio-demographic details, as well as some health data, before moving on to provide a more personal perspective on the life of centenarians as reported in the Quality of Life (QoL) survey.

How many Australian centenarians?

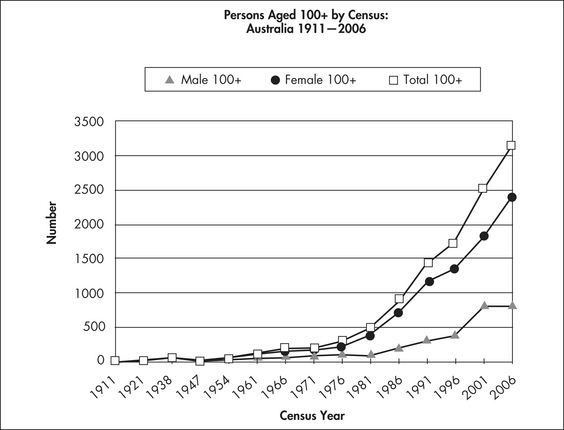

While life expectancy at all ages has continued to increase, the Australian census, from the early 1900s, consistently reported people living to very old ages (Fig 3.1). The census records show that there were 64 living centenarians recorded at the 1911 census, and that 27 centenarians had died in that year. Information on their deaths was provided in the 1911 Commonwealth Year Book (ABS 2001). However, the Statistical Registrar-General commented in relation to ‘abnormally high ages’ that “… no absolute reliance can be placed on the accuracy of the ages shewn (sic) owing to the well-known tendency of very old people to overstate their ages” (ABS 2001: 192). Not only was he making reference to the important issue of age validation or age misreporting, but also to the poor record-keeping on registration of births in other countries of origin. For example, only two of the 14 male centenarians who died in 1911 were born in Australia. The majority were born in England, and two were born in China. Ten of the 14 were more than 100 years of age, the oldest being 108 years. Only three were on the public old age pension whereas the rest were listed as having an occupation. Similarly, of the 13 female centenarians who had died in 1911, seven were aged more than 100 years, with the oldest being 105 years. The most frequent cause of death was listed as ‘senility’, although ‘rodent ulcers’, ‘gangrene’, ‘diarrhoea’, ‘heart disease’ and ‘influenza’ were also cited.

There were low numbers of centenarians until the 1970s after which the number of centenarians and their growth rate increased substantially. There was then a 47% average five-yearly increase for people in this age group during the years 1971 to 2006. The increase in females was greater than the increase for males, with females representing 79% of persons aged 99 years or more at the 1996 census (ABS 1996), but this dropped slightly to 75% at the 2006 census. Similarly, the gender ratio for this group at that 1996 census was 27 males per 100 females, but this increased to 34 males per 100 females for 2006. As above, and as can be seen from the chart (Fig 3.1), the reported increase in male centenarians over the last 10 year period may need further investigation to substantiate this rapid increase. Overall, however, despite these data difficulties, it is clear that there is a very marked increase in numbers of people aged 100 years or more in Australia.

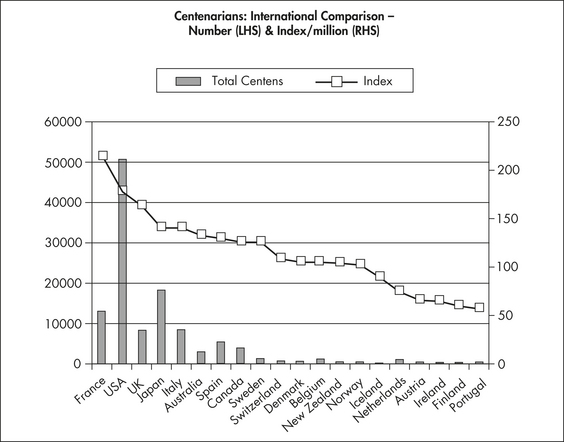

The Australian census for 2006 is the most recent count of centenarians and the ABS used those census figures (which, on the census form, was tick a box for age 100 years or more), along with birth, death and migration data, to develop the estimated resident population (ERP) of Australia. According to the ABS, the census tends to under-enumerate (ABS 2002), although it is not clear how much this impacts on centenarians. However, the 2006 census count of 3157 centenarians (802 males and 2355 [75%] females) is in accord with the numbers one would expect in an advanced industrial economy of about 100 centenarians per million of the total population. The actual rate of 133 would, using Ruisdael’s survey data (2003), mean Australia is about sixth in the top 10 countries for the centenarians per million index figure, but just outside (11th) of the top 10 developed countries for number of centenarians. Ruisdael’s data in Figure 3.2 shows that France, USA, UK, Japan and Italy would rate above Australia on the index.

In trying to understand what is behind this apparent increase in Australian centenarians, I applied Thatcher’s (1999) methodology to current and historical ABS data and life tables to identify relevant individual factors, presented in Table 3.1 below.

Table 3.1 Factors related to increase in Australian centenarians

| CAUSE | MALE | FEMALE |

|---|---|---|

| Increase in births (1860 to 1899) | 2.14 | 2.14 |

| Improved survival from birth to age 80 years | 3.96 | 3.92 |

| Improved survival from age 80 to 100 years | 7.14 | 13.1 |

| Changes above age 100 (Ratio 100+:100, 1985–1995) | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Reduced probability of death at age 100 (1953–1995) | 1.8 | 1.6 |

| Product of above factors | 21.8 | 17.6 |

Applying this to the period up to 2001, the product of the factors shown accounts for the approximately 40-fold increase in Australian centenarians, from 64 in 1911 to around 2500 in 2001. Among the individual factors, improved survival from age 80 to 100 years accounts for about half of the total increase, and females play a larger role in this. However, in the overall product of factors, males account for a higher proportion of the overall increase than do females. As Poon (1992) says, there is no single magic bullet to explain this late life survival but more likely a constellation of factors, including Australia’s pervasive and effective health care system. Changes above age 100 years so far account for only a small component of the overall increase in centenarians. However, not a lot is known about these older centenarian age groups, as detailed below. Before moving to look briefly at them, we will look at other data from another census (2001), where greater detail data is available in terms of what it can tell us about very old age in Australia.

Marital status and living arrangements

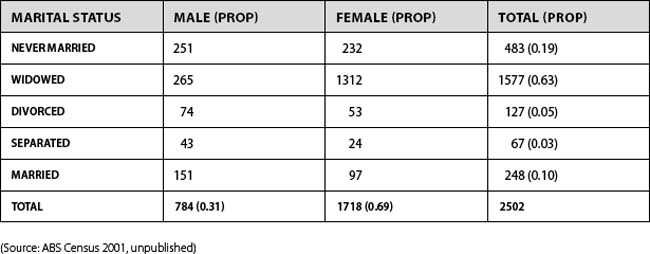

The census data provide some information about the number of centenarians still living in the community. For example, there is a statistically significant difference in marital status between male and female centenarians (χ2 321.7, 4df, p<.001) (Table 3.2). There is a much greater proportion of males never married (32%) than females (14%), and an even greater proportion of males still married (19%) than females (6%). Females, on the other hand, are far more likely to be widowed (76%).

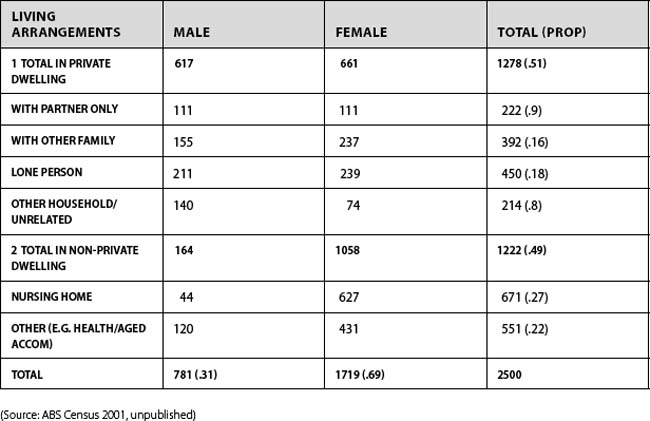

Amazingly, more than half (51%) of all centenarians live in the community in private dwellings, while only 49% are in health and retirement related accommodation (Table 3.3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

While it is essential that we understand why so many more people are reaching very old age, we also need to know the quality of their life at this milestone age.

While it is essential that we understand why so many more people are reaching very old age, we also need to know the quality of their life at this milestone age.

There were low numbers of centenarians until the 1970s after which the number of centenarians and their growth rate increased substantially.

There were low numbers of centenarians until the 1970s after which the number of centenarians and their growth rate increased substantially.

The 2006 Australian census counted 3157 centenarians (802 males and 2355 [75%] females).

The 2006 Australian census counted 3157 centenarians (802 males and 2355 [75%] females). There is no single magic bullet to explain this late life survival but more likely a constellation of factors.

There is no single magic bullet to explain this late life survival but more likely a constellation of factors.