Substance Use Disorders

Charon Burda*

Focus Questions

How are substance abuse and dependence defined?

What is the process of addiction?

What theory of addiction is most relevant to community/public health nursing practice?

What is the extent of substance use disorders (SUDs)?

How can community/public health nurses help prevent addictions?

How can community/public health nurses help prevent fetal alcohol syndrome and related disorders?

How can community/public health nurses assist individuals and families recovering from addictions?

What community resources exist to help with addiction problems and how is this picture changing?

Key Terms

Abstinence

Addiction

Brief interventions

Co-dependence

Compulsive drug-seeking behavior

Co-occurring disorders (Comorbidity)

Detoxification

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASDs)

Impaired nurses

Medication-assisted treatment (MAT)

Overdose

Person first language

Pseudoaddiction

Recovery

Recovery-oriented systems of care (ROSC)

Substance abuse

Substance dependence

Substance use disorders (SUDs)

Tolerance

Withdrawal

Community public health nurses are on the forefront of identifying individuals who require specialized help. Nurses need to be knowledgeable about the latest evidence-based care as well as implement the most effective interventions available for those with substance use disorders (SUDs). This vulnerable population imposes a high level of need for informed, culturally sensitive, professional nursing care. Nurses need to be aware of the signs and symptoms of SUDs and develop relationships with appropriate referral sources. Clients should be carefully guided to appropriate, cooperating facilities, with follow-up by staff to ensure that they receive appropriate care. The most important principle in addiction treatment is “No wrong door” (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment [CSAT], 2000). The health care delivery system, and every provider in it, has a responsibility to address the range of client need, wherever and whenever a client presents for care. Every “door” of the health care delivery system should be the right door to receive assistance and referral. Community/public health nurses need to continue advocating for appropriate treatment and resource allocations for this vulnerable and stigmatized population.

Background of addiction

Many psychoactive substances are plant made (nicotine, caffeine, morphine, cocaine, mescaline, and tetrahydrocannabinol); alcohol is a natural product of sugar fermentation by yeast. Due to the accessibility of these substances in nature, the use of psychoactive drugs has been a part of the human experience since antiquity. Major events that have influenced our attitude and behavior regarding drug use have occurred historically. For example, tobacco export played an important part in the economy of the United States early in its history. The invention of the matchstick, which allowed portable fire, and machines that could roll thousands of cigarettes quickly fueled the tobacco industry.

During the nineteenth century, advances in chemistry made it possible to purify the active ingredient of opium (morphine) and coca (cocaine) allowing these drugs to be taken in more concentrated form, thus increasing their addictive potential. The hypodermic syringe had already been developed in 1858 and helped spread the use of morphine in treating wounded and ill soldiers during the Civil War. Early pharmaceuticals and patent medicines, tonics, and elixirs sold over the counter contained liberal amounts of opium, cocaine, or alcohol and were not regulated at all until 1906 when the Pure Food and Drug Act created the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to regulate labeling and assess the potential hazards and benefits of all new medications.

In contrast, the behavior and methods of drug use fuel legislation and society’s perspective on addiction. For example, in 1914, roughly 1 of every 400 Americans was an opiate addict. At that time, the Harrison Act was passed, regulating the dispensing and use of opioid drugs and cocaine. Prior to the Harrison Act, users procured drugs from their physicians; consequently, this Act gave rise to street dealers and illegal drug trade.

Medicalization of drug addiction began in the second half of the twentieth century but was not taken seriously until the 1950s when the World Health Organization (WHO), followed by the American Medical Association (AMA), declared alcoholism to be a disease. In 1970, the Controlled Substances Act replaced or updated all previous federal legislation and led to the creation of the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA).

Since the “War on Drugs,” declared by President Richard Nixon in the 1970s and continued by President George H. W. Bush, public policy has shifted away from an illness model to a deterrence model. This shift resulted in the Crime Bill signed by President Bill Clinton in 1994, which called for life imprisonment for those committing three consecutive drug offenses (“three strikes”). President George W. Bush continued the effort by reauthorizing the Drug-free Communities Act, which concentrated the prevention efforts in the most drug-ridden communities. He also created a national drug control strategy that included efforts to limit drug supplies, reduce substance demands, and provide effective treatment to individuals with SUDs.

As of 2011, President Obama’s pledge was to treat illegal drug use more as a public health issue than a criminal justice problem. While the evidence-based solutions for SUDs require increased prevention and treatment, the funding of such efforts lags behind. For example, in 2009, the budget of the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) allotted 35% for prevention and treatment research to reduce demand, while law enforcement to reduce supply received 65% (The White House, 2008).

Budget allocation is a reflection of priority. When treatment and prevention are not the central focus, the current outcomes of increasing substance use and low rates of treatment availability for addiction recur in society. Since we are not paying for prevention, it is not readily accessible (Fornili, 2009). DiClemente (2006) articulated the current challenge in thinking about addiction and how one’s thoughts change the offered responses. He stated:

“If addiction is seen as a moral failing, it will be condemned. If seen as a deficit in knowledge, it will be educated. If the addiction is viewed as an acceptable aberration, it will be tolerated. If the addiction is considered illegal, it will be prosecuted. If addiction is viewed as an illness, it will be treated.”

(DiClemente 2006, p. vii)

Impact of Substance Use on Society

Drug addiction is a chronic, relapsing, compulsive disorder. Addiction presents a major burden on the health and financial resources of our society. Damage to human life is described in terms of loss of “disability-adjusted life years” (DALYs). This measure takes into account the number of years lost due to premature deaths as well as the years spent living with disability. Worldwide, psychoactive drugs are responsible for 8.9% of all DALYs lost. The main impact is not due to illicit drugs (0.8% of DALYs) but to alcohol (4%) and tobacco (4.1%).

For years the United States has been spending tens of billions of dollars a year in an attempt to control the trafficking and use of illicit drugs. Most of those dollars have been used to support stricter enforcement. When calculating the actual cost of addiction on society, there are many factors to consider. Increased chronic illnesses that jeopardize public health and resources include, but are not limited to, related cases of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS), hepatitis, asthma, diabetes, cancer, and mental illnesses. The most recent cost analysis by the Department of Justice’s National Drug Intelligence Center (NDIC) included health care, crime, and the associated loss of productivity for drug abuse which were estimated at $193 billion in 2007 (NDIC, 2011).

A further complexity is the realization that approximately 25% of individuals with an SUD are also diagnosed with a concurrent mental health diagnoses (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2007). Substance use significantly affects not only the user but also his or her immediate and extended family as well as the health and safety of that person’s community. The full impact of substance use is evident when assessing teenage pregnancy rates, HIV/AIDS, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), domestic violence, child abuse, motor vehicle accidents, aggression, crime, homicide and suicide (SAMHSA, 2006).

Understanding these far-reaching negative consequences is the key for health care professionals in educating and developing solutions to move forward. This chapter presents a broad overview of substance use and addiction. Theories of addiction, interventions, and community resources addressing problems relevant to community/public health nursing are discussed.

Healthy People 2020 Objectives

The Healthy People 2020 objectives place a strong emphasis on education at the earliest ages to support prevention efforts and maintaining cost containment in the future. A primary focus is to discourage the initial use of substances such as alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drugs among adolescents and children. (See Healthy People 2020 Objectives box.)

Definitions

Distinguishing between the terms abuse, dependence, and addiction has been difficult because they are often used interchangeably and incorrectly. For purposes of clarification in this chapter, definitions are provided. Substance use disorder is an overarching term used to encompass both substance abuse and substance dependence. The gold standard for identifying and diagnosing clusters of behaviors is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR). Published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA), it includes criteria for all recognized mental health disorders for both children and adults. Accurate assessment of a diagnosis directs treatment options.

Substance abuse as defined in the DSM-IV-TR refers to a maladaptive pattern of substance use manifested by recurrent and significant adverse consequences occurring within a 12-month period. Individuals may repeatedly fail to fulfill major role obligations, repeatedly use a substance in a situation in which it is

physically hazardous (such as driving while intoxicated), have multiple legal problems, or have recurrent social or interpersonal problems because of their substance use (APA, 2000).

Substance dependence refers to a cluster of cognitive, behavioral, and physiological symptoms indicating that the individual continues to use a substance despite significant substance-related problems. Unlike substance abuse, substance dependence also includes symptoms of tolerance, withdrawal, and a pattern of compulsive use. Dependence includes symptoms of taking larger amounts of drugs than intended. There is often marked difficulty in being able to decrease drug intake. A majority of a person’s time revolves around the activities to obtain and maintain their drug use. Finally, despite acknowledgement that the drug use is a danger to their individual health, relationships, employment, and social well-being, they continue to use (APA, 2000).

The APA is in the process of developing a national consensus updating the DSM-V. The new DSM-V will refer to “addictions and related disorders,” and will eliminate the category of dependence to better differentiate between the compulsive drug-seeking behavior of addiction and normal responses of tolerance and withdrawal that some experience when using prescribed medications.

Addiction, is defined by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA, 2010) as a chronic, relapsing brain disease characterized by compulsive drug seeking despite negative consequences. The definition of a brain disease acknowledges that the brain undergoes significant changes in its structure and function because of illicit substances. Some of these neurochemical and molecular changes may be permanent. As defined by the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM), addiction also encompasses the genetic, psychosocial, and environmental influences in the development of substance use, abuse, and dependence (West, 2001). This definition conceptualizes addiction as a chronic disease similar to hypertension or diabetes. As with all chronic diseases, addiction is a pathological condition that has a clearly measurable, characteristic physiology and neurobiology. This definition of addiction is consistent with research that has identified genetic factors as well as environmental factors that precipitate relapse.

Another important distinction in addiction is pseudoaddiction, which includes the characteristics of drug-seeking compulsive behaviors that are consistent with addiction. The behaviors are the same but the underlying cause is different. Pseudoaddiction occurs in people experiencing inadequate medication management for pain relief. Once the pain is adequately treated, the person no longer abuses the medication. This is a very important concept for all health care practitioners to understand as ineffective pain management directly affects the person’s ability to heal (Savage, 2003).

Theories of Addiction

Alcohol and drug addictions appear to be part of a larger constellation of related disorders, thought to be clustered around some underlying biological or genetic mechanism, or multifactorial cause that is yet to be discovered. A recent trend has been to create models of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework that provides a broader, more holistic perspective on addiction and its prevention, treatment, and research. This model is being accepted more widely because it can more adequately explain the complex nature of addiction.

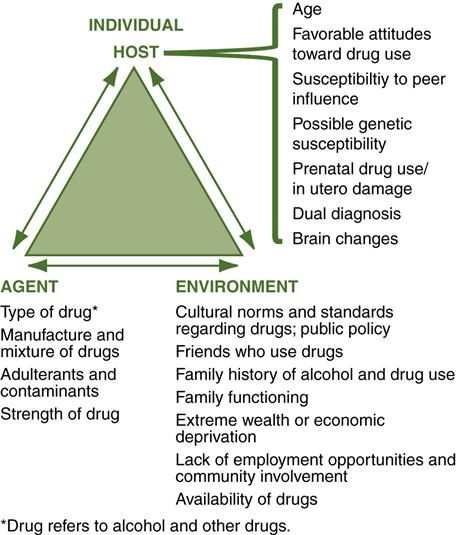

The biopsychosocial model of addiction that best fits community/public health nursing is that of the public health model (Figure 25-1). The public health model of addiction stresses that biological, psychological, pharmacological, and social factors constantly interact and influence the problem of addiction in any person or group of people. As described by Mosher (1996), in the public health model, the host is the person who has the addiction; the agent is the alcohol or other drug sufficient in quantity to cause harm to the host; and the environment includes the social, economic, physical, political, and cultural settings in which the host and agent interact. The environment also includes the meanings, values, and norms assigned to a drug by its culture, community, and society.

It is true that alcohol and other drug addictions could not exist if the alcohol or illicit drugs were not available. Therefore, the role of addicting drugs and alcohol is that of the agent in the public health model. The addiction does not occur solely because of the agent. Some host and environmental factors also contribute to the development of addiction.

Many of the repetitive behaviors associated with addictions involve multiple brain reward regions and neurotransmitters that regulate normal consumptive behaviors necessary for survival, for example, eating and drinking (Guardia et al., 2000; NIDA, 1994). Scientists are involved in a widely publicized search for genes that predispose persons to alcoholism and other addictions by regulating brain function. Changes in the brain are a major cause of alcohol and other drug addictions. Prescott and colleagues (1999) and other researchers have conducted twin studies that demonstrate a genetic vulnerability to alcoholism. Identical twins of alcoholic parents have more than a 60% chance and fraternal twins a 30% chance of becoming alcoholics.

Numerous environmental conditions such as physical and emotional trauma also play a part in the expression of addictions (Sansone et al., 2009). Other environmental risk factors include economic and social deprivation, low neighborhood attachment, community norms that facilitate drug use and abuse, and availability of alcohol and other drugs (Trigoboff & Wilson, 2004).

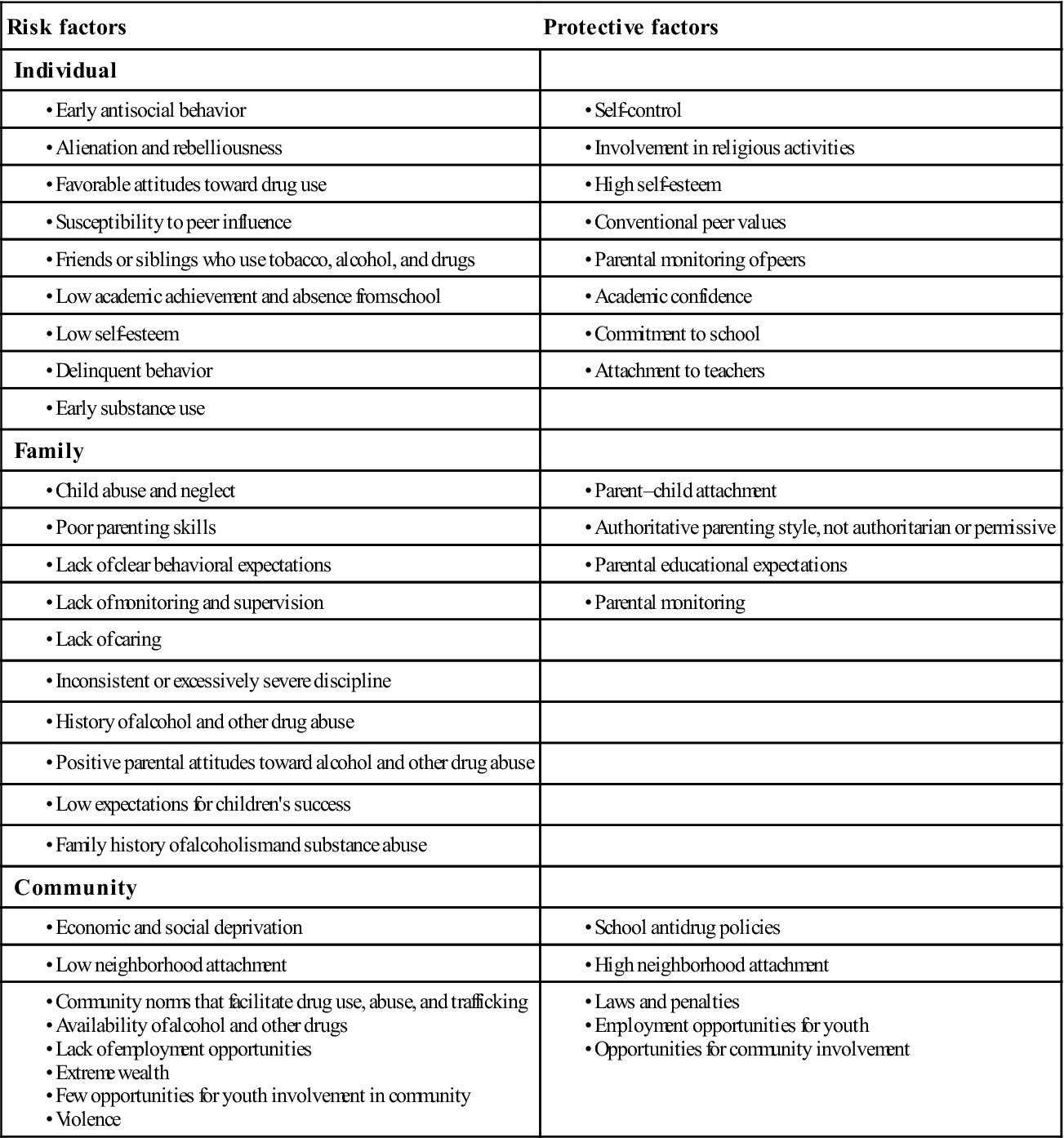

Genetic vulnerability and environmental factors interact to produce addiction; however, addiction can apparently be induced without genetic vulnerability through the impact of the environment alone. Mosher (1996, p. 244) stated, “Environmental factors—the forces that bring the agent into injurious contact with the host—are critical in the public health model of addiction. A high-risk environment creates a myriad of opportunities for public health harm.” High-risk environments can be found in the family, workplace, school, community, and war zones (Table 25-1).

Table 25-1

Risk and Protective Factors for Substance Use

| Risk factors | Protective factors |

| Individual | |

| Family | |

| Community | |

• Violence |

The Process of Addiction

There are two types of progression in drug use. In one type, known as the gateway theory of drug use, adolescents begin experimenting with alcohol or tobacco, sometimes later progressing to marijuana. In a small percentage of cases, they move on to other types of drugs as they get older. The initial lure may be curiosity, peer pressure, stressors, or simply mimicking adult behaviors.

A second type of progression involves changes in the amount, pattern, and consequences of drug use. The first stage in the process of addiction may involve experimental and social use but, in the second stage, use becomes a regular occurrence and begins to affect the user’s health and well-being. Use might occur during the day and while alone or with others. Substances may be used to manipulate varying emotions.

Behavioral indicators in the second stage can include a decline in school or work performance, mood swings, personality changes, lying and conning, change in friendships, decrease in extracurricular activities, adoption of a drug culture appearance, conflicts with family members, and preoccupation with procuring and using alcohol and other drugs. As continued and increased use progresses, dependency develops. Alcohol and drugs may be used daily or continuously to avoid negative emotions. Use becomes unmanageable as the individual attempts to achieve homeostasis and feel normal. Behavioral indicators of dependence include physical deterioration, cognitive changes, lack of concern over being discovered, and absence from home, job, or other places of responsibility (SAMHSA, 1994).

Addiction is a disease of the brain. Abused substances activate the same brain circuits as do behaviors of basic survival such as eating and sex. During repeated drug use, the brain registers the increased pleasure, which corresponds with increases in a neurotransmitter called dopamine. Dopamine is one of many neurotransmitters, and it is responsible for feelings of pleasure and euphoria. The route it travels in the brain is called the pleasure pathway. Once this system is activated, the brain wants to keep the dopamine levels high to enhance the feelings of intense pleasure. The user is then placed in a chronic “cycle of distress” to keep the drug available. Once the pleasure has diminished, the need to decrease the anticipated distress of not having the drug is activated. Drugs that are abused provide very large amounts of dopamine to the brain. In response to the increased dopamine, the brain regulates itself by decreasing the normal production of dopamine. Over time, dopamine regulation becomes altered, and the user is unable to experience pleasure even from the drugs they crave. The abilities to control decision making and judgment and to manage desires and emotion are all negatively impacted.

Researchers now believe that the drug-seeking behavior is a primitive response that occurs prior to conscious awareness. The limbic system, specifically the nucleus accumbens, is the area of the brain that starts the drug-seeking addictive behavior in motion. This knowledge questions the thinking that addiction is related to willpower and free choice (Burns & Bechara, 2007).

Researchers can now visualize and compare brain changes using brain imaging. Studies show that the brains of heavy chronic drinkers shrink, specifically the frontal lobe, which is responsible for decision making and judgment. The cerebellum that governs gait and balance also shrinks. Withdrawal symptoms occur because the body and the brain have been trying to create a balance with the continual use of a drug. When the drug is no longer available, the systems of the body become overcompensated and unbalanced.

Effects of alcohol and drugs on the body

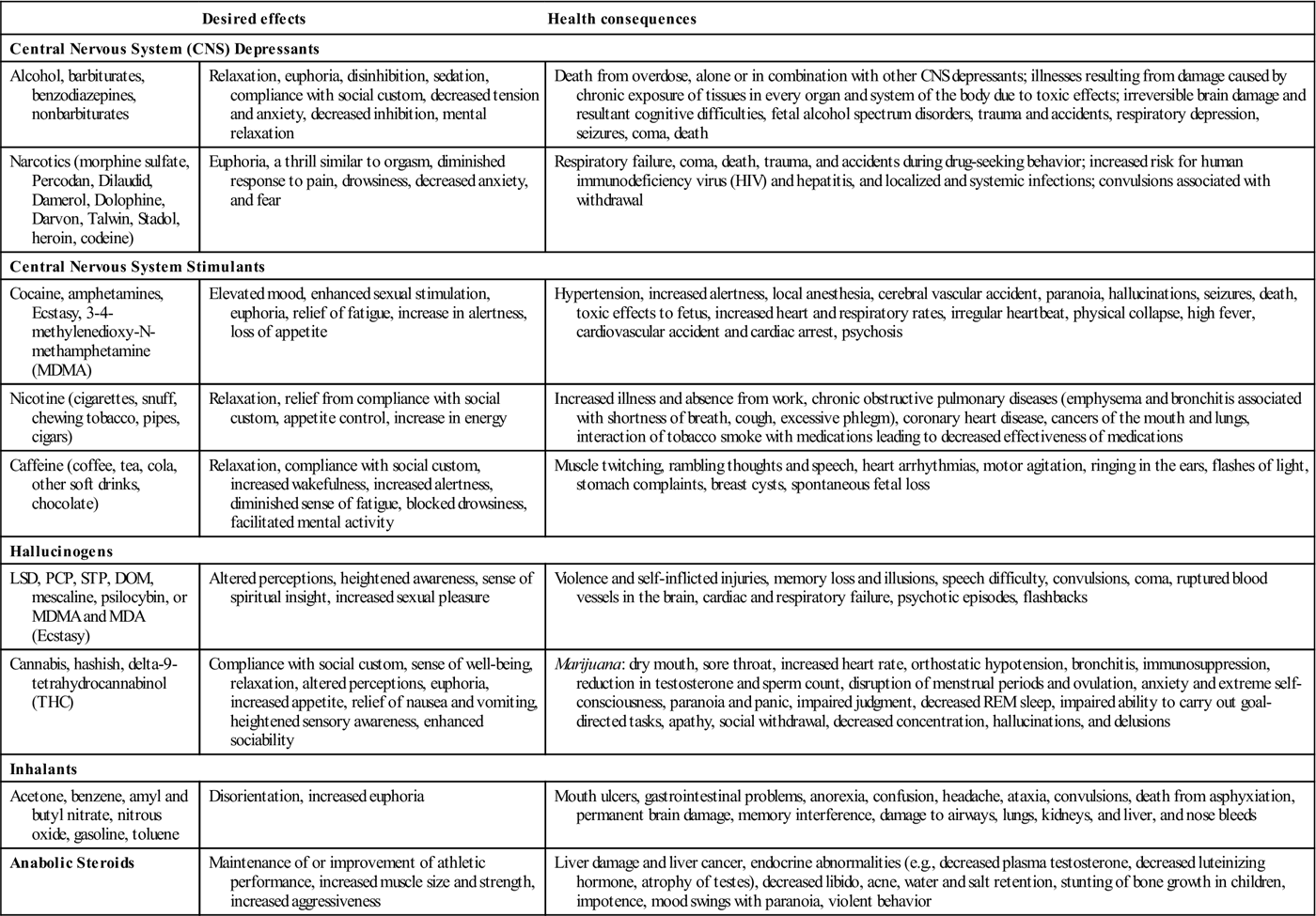

Drugs are often categorized by the effects they have on the human body (Table 25-2). (See also National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2011 at http://www.nida.nih.gov/consequences/.) Two major categories of addictive drugs are central nervous system (CNS) depressants and CNS stimulants. CNS depressants include alcohol and certain drugs (see Table 25-2). These drugs depress CNS function and behavior to cause a sense of relaxation and drowsiness. At high doses, mental clouding occurs, along with a loss of coordination, intoxication, and coma. Analgesics frequently have CNS-depressant qualities, although their principal effect is to reduce the perception of pain. Narcotics or opiate-like drugs produce relaxation and sleep. They may also produce a sense of euphoria and a desire to keep taking the drug. Drugs in this class also include oxycodone (e.g., Oxycontin) and hydrocodone (e.g., Vicodin). CNS stimulants produce increased electrical activity in the brain and behavioral arousal, alertness, and a sense of well-being. Drugs in this class include amphetamines (e.g., Adderal), cocaine, caffeine, methylphenidate (e.g., Ritalin, Concerta), and 3-4-methylenedioxy-N-methamphetamine (MDMA; “Ecstasy”).

Table 25-2

Effects of Selected Drugs and Alcohol

| Desired effects | Health consequences | |

| Central Nervous System (CNS) Depressants | ||

| Alcohol, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, nonbarbiturates | Relaxation, euphoria, disinhibition, sedation, compliance with social custom, decreased tension and anxiety, decreased inhibition, mental relaxation | Death from overdose, alone or in combination with other CNS depressants; illnesses resulting from damage caused by chronic exposure of tissues in every organ and system of the body due to toxic effects; irreversible brain damage and resultant cognitive difficulties, fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, trauma and accidents, respiratory depression, seizures, coma, death |

| Narcotics (morphine sulfate, Percodan, Dilaudid, Damerol, Dolophine, Darvon, Talwin, Stadol, heroin, codeine) | Euphoria, a thrill similar to orgasm, diminished response to pain, drowsiness, decreased anxiety, and fear | Respiratory failure, coma, death, trauma, and accidents during drug-seeking behavior; increased risk for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis, and localized and systemic infections; convulsions associated with withdrawal |

| Central Nervous System Stimulants | ||

| Cocaine, amphetamines, Ecstasy, 3-4-methylenedioxy-N-methamphetamine (MDMA) | Elevated mood, enhanced sexual stimulation, euphoria, relief of fatigue, increase in alertness, loss of appetite | Hypertension, increased alertness, local anesthesia, cerebral vascular accident, paranoia, hallucinations, seizures, death, toxic effects to fetus, increased heart and respiratory rates, irregular heartbeat, physical collapse, high fever, cardiovascular accident and cardiac arrest, psychosis |

| Nicotine (cigarettes, snuff, chewing tobacco, pipes, cigars) | Relaxation, relief from compliance with social custom, appetite control, increase in energy | Increased illness and absence from work, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (emphysema and bronchitis associated with shortness of breath, cough, excessive phlegm), coronary heart disease, cancers of the mouth and lungs, interaction of tobacco smoke with medications leading to decreased effectiveness of medications |

| Caffeine (coffee, tea, cola, other soft drinks, chocolate) | Relaxation, compliance with social custom, increased wakefulness, increased alertness, diminished sense of fatigue, blocked drowsiness, facilitated mental activity | Muscle twitching, rambling thoughts and speech, heart arrhythmias, motor agitation, ringing in the ears, flashes of light, stomach complaints, breast cysts, spontaneous fetal loss |

| Hallucinogens | ||

| LSD, PCP, STP, DOM, mescaline, psilocybin, or MDMA and MDA (Ecstasy) | Altered perceptions, heightened awareness, sense of spiritual insight, increased sexual pleasure | Violence and self-inflicted injuries, memory loss and illusions, speech difficulty, convulsions, coma, ruptured blood vessels in the brain, cardiac and respiratory failure, psychotic episodes, flashbacks |

| Cannabis, hashish, delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) | Compliance with social custom, sense of well-being, relaxation, altered perceptions, euphoria, increased appetite, relief of nausea and vomiting, heightened sensory awareness, enhanced sociability | Marijuana: dry mouth, sore throat, increased heart rate, orthostatic hypotension, bronchitis, immunosuppression, reduction in testosterone and sperm count, disruption of menstrual periods and ovulation, anxiety and extreme self-consciousness, paranoia and panic, impaired judgment, decreased REM sleep, impaired ability to carry out goal-directed tasks, apathy, social withdrawal, decreased concentration, hallucinations, and delusions |

| Inhalants | ||

| Acetone, benzene, amyl and butyl nitrate, nitrous oxide, gasoline, toluene | Disorientation, increased euphoria | Mouth ulcers, gastrointestinal problems, anorexia, confusion, headache, ataxia, convulsions, death from asphyxiation, permanent brain damage, memory interference, damage to airways, lungs, kidneys, and liver, and nose bleeds |

| Anabolic Steroids | Maintenance of or improvement of athletic performance, increased muscle size and strength, increased aggressiveness | Liver damage and liver cancer, endocrine abnormalities (e.g., decreased plasma testosterone, decreased luteinizing hormone, atrophy of testes), decreased libido, acne, water and salt retention, stunting of bone growth in children, impotence, mood swings with paranoia, violent behavior |

Hallucinogens, or mind-altering drugs, including marijuana, alter one’s perception of reality. LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) is the most potent hallucinogen. Ecstasy, popular among children and adolescents, has the properties of both a stimulant and a hallucinogen. Inhalant use is most common among children and adolescents because inhalants are affordable and accessible. Inhalants include aerosols, gasoline, correction fluid, cleaning solutions, and other commonly used chemicals. Irreversible effects can be hearing loss, limb spasms, CNS or brain damage, or bone marrow damage. Death from heart failure or suffocation (inhalants displace oxygen in the lungs) can occur.

Tolerance is the capacity to ingest more of the substance than other persons without showing impaired function. Because tolerance develops with repeated use over a period of time, tolerance can be an early sign that the person is developing an addiction. In the United States, alcohol tolerance often remains unrecognized because of the cultural myth that a man should be able to “hold his liquor.” The consequence is that signs of tolerance that could lead to early intervention are often overlooked, and the addiction progresses. A late-developing symptom of chronic addiction is a reduced tolerance for high blood levels of alcohol or other drugs, which develops when the diseased liver can no longer process the ingested substance efficiently.

Most people would define an overdose as taking too much of a drug. How much is “too much”? For a drug to which one can develop tolerance, for example, heroin, there is really no predictable or standardized dose that can be considered “too much” for everyone. Tolerance and experience are the predictors of the effects. An overdose amount for a novice user may not produce any desired effect in an experienced user. In the public health context, an overdose is generally defined as exhibition of symptoms that indicate an individual has taken a level of a drug (or combination of drugs) that exceeds the person’s individual tolerance. In the case of heroin, which is a respiratory depressant, these symptoms include loss of consciousness; breathing that slows significantly or stops; and the person’s lips, skin or nails turning blue from lack of oxygen.

Common Drugs

Alcohol

Alcohol is one of the most frequently used problematic drugs. Ethyl alcohol, or ethanol, is an intoxicating ingredient found in beer, wine, and liquor. A standard drink equals 0.6 ounces of pure ethanol, or 12 ounces of beer; 8 ounces of malt liquor; 5 ounces of wine; or 1.5 ounces (a “shot”) of 80-proof distilled spirits or liquor (e.g., gin, rum, vodka, or whiskey). Alcohol is absorbed through the digestive tract into the bloodstream, and some of the factors that affect absorption include the amount consumed in a given time, the type and amount of food in the stomach, the drinker’s size, and the drinker’s gender.

Alcohol is not excreted from or stored anywhere in the body before metabolism; it is distributed throughout the body fluids. It does not distribute much into fatty tissues; therefore, at a given weight, a female who has a higher proportion of body fat than a male has less volume in which to distribute the alcohol. This explains why the blood alcohol levels (BAC) are higher for females than males of the same weight.

Alcohol is toxic. A self-protective vomiting reflex occurs at a BAC level of about 0.12% but only if consumption is rapid. However, if BAC levels are increased gradually, the vomiting center is depressed, and the individual can drink up to lethal concentrations. Death from acute alcohol intoxication is often the result of respiratory failure.

Marijuana

The most commonly used illegal drug is marijuana, which is prepared from the leafy materials of the cannabis plant. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is one of the psychoactive components found in the flowering tops, leaves, and stalks. Hashish is the most potent plant preparation, as it is pure concentrated plant resin. When smoked, THC is rapidly absorbed in the blood. Once distributed to the brain, it influences pleasure, memory, thought, concentration, sensory and time perception, and coordinated movement.

Marijuana also affects the heart. Some studies show that a marijuana users’ risk of heart attack more than quadruples in the first hour after smoking the drug. This could be a result of marijuana’s effects on blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen-carrying capacity of blood. Even infrequent use can cause burning and stinging of the mouth and the throat, which is often accompanied by a heavy cough. Regular use may have similar effects on the lungs as those of smoking cigarettes. Marijuana smoke contains 50% to 70% more carcinogenic hydrocarbons than does tobacco smoke, and marijuana users inhale more deeply than do tobacco smokers (Mayo Clinic, 2006).

In addition to being a social drug, marijuana has also been studied for its therapeutic abilities. Some of its potential benefits are alleviation of nausea, vomiting, and the loss of appetite resulting from chemotherapy; reduction of intraocular pressure in glaucoma; reduction of muscle spasms; and relief from mild to moderate chronic pain. A legal form is available by prescription in some states.

Opiates

Opiates (e.g., morphine and codeine) are derived from the opium poppy. The major therapeutic indication for this drug group is pain relief. However, because this group of drugs can also cause constipation, it has saved the lives of many people with dysentery. Narcotics have been used to counteract diarrhea and the resulting dehydration in both young and older persons in developing countries. Heroin is two to three times more potent than morphine because heroin’s additional two acetyl groups permit it to penetrate the blood–brain barrier more readily. Heroin users live on a cyclic schedule, requiring a dose every 4 to 6 hours. The short-term effects of heroin include a surge of euphoria and clouded thinking, followed by alternating wakeful and drowsy states.

Stimulants

Cocaine and amphetamines are considered the most addictive drugs consumed by man. Stimulants keep the user mentally and physically alert. Cocaine has multiple routes of administration: orally, by injection, or by inhalation. Its form often dictates administration. For example, coca leaves contain between 0.1% and 0.9% cocaine, and chewing cocaine rarely causes any social or medical problems for the user. Drinking coca tea tends to soothe the stomach. While powder cocaine, which has come to symbolize the rich and famous, is expensive, cocaine in its lump form (“crack”) is very inexpensive. There is great variability in the uptake and metabolism of cocaine, so a lethal dose is difficult to estimate. Cocaine can trigger cardiac changes and allergic reactions to the drug or to other additives found in street cocaine. Chronic toxicity may lead to malnourishment, and bingers can experience irritability and paranoia to the extent of experiencing hallucinations.

Amphetamines, synthesized in 1932, were first used via inhalation to dilate nasal and bronchial passages of asthmatics and in products for treatment of stuffy noses. However, in the 1970s, they went from being widely used and accepted to being tightly restricted and associated with drug abusing “hippies.” As a reaction, illicit, clandestine laboratories began making methamphetamine. Use of the smoked form, known as “ice” or “crystal meth,” quickly spread from the west coast to the rural midwest of the United States. Methamphetamine increases wakefulness and physical activity, produces rapid heart rate, irregular heartbeat, and increased blood pressure and body temperature.

Club Drugs

Teenagers and young adults at bars, nightclubs, concerts, and parties most often use “club drugs.” Club drugs include MDMA (Ecstasy), gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB), flunitrazepam (Rohypnol), ketamine, and others. They have varying effects. MDMA is a synthetic drug that has stimulant and psychoactive properties. It is taken orally as a capsule or tablet. Negative effects experienced on consumption of the drug Ecstasy include blurred vision, muscle tension, nausea, involuntary teeth clenching, and sweating as well as psychological effects such as anxiety, depression, paranoia, memory loss, and insomnia. Users, specifically those in raves and clubs, may also experience acute dehydration if they are active and are not consuming enough water. MDMA, by itself, is not fatal but can lead to death when accompanied by overheating and dehydration and by inhibiting urine production leading to fatal buildup of fluid in the tissues. MDMA is one of two drugs, the other being alcohol, for which there is significant evidence that it destroys brain cells. Ketamine distorts perception and produces feelings of detachment from the environment and self, while GHB and Rohypnol have sedating effects. GHB abuse can cause coma and seizures. High doses of ketamine can cause delirium and amnesia. Rohypnol can incapacitate the users and cause amnesia and can be lethal, especially when mixed with alcohol.

Prescription Drugs

Misuse of prescription drugs is becoming an increasing problem, especially among America’s youth. Second only to marijuana, it is the most prevalent form of illegal drug use among adolescents and young adults (SAMHSA, 2007). There are two types of misuse: Prescription medication misuse, which is defined as an intentional, risk behavior that involves the improper use of one’s own prescription medications, motivated by a desire to treat one’s symptoms or experiment, or for any other reason. It is a form of nonadherence because the user either fails to use the medication exactly as prescribed (e.g., taking the medication too frequently, or increasing the medication dose without supervision). Another form of misuse is a risky behavior that involves the intentional use of someone else’s prescription medication motivated only by the desire to alleviate symptoms that may be related to an actual or perceived health problem, to experiment, to get high, or to create an altered state.

Drug diversion and sources of nonmedical prescription drug use include “doctor shopping,” leftover supplies from physical illness, friends and peers, buying prescription drugs on the streets, pharmacy and hospital thefts, and stealing from family member’s medicine cabinet (Boyd et al., 2007; Inciardi et al., 2007; Johnston et al., 2008).

Over-the-Counter Medications

The abuse of over-the-counter (OTC) cold medications by adolescents is also on the rise in the United States. There has been a 10-fold increase in cold medicine abuse during 1990 to 2004, with a 15-fold increase among those aged 9 to 17 years (Levine, 2007). An ingredient in many cough and cold remedies, dextromethorphan hydrobromide, or more commonly known by its street name DXM, is the most popular antitussive medication in the United States. Intoxication by DXM occurs by consuming large doses which can lead to different affects ranging from mild distortions of color or sound to “out of body” dissociative sensations, visual hallucinations, and total loss of motor control.

Other OTC products used for weight control and sleep aids are monitored by the FDA for their toxicity and abuse potential; however, herbal products that may also have some psychoactive properties are not (SAMHSA, 2007). Energy drinks and many nonprescription drugs contain large amounts of caffeine. The absorption is rapid after oral intake, with peak levels occurring 30 minutes after ingestion. Caffeine is not extremely toxic, and overdoses are rare but can happen. Death occurs from convulsions, which lead to respiratory arrest. While many people enjoy the stimulating effects of caffeine, its unpleasant symptoms such as irritability, nervousness, insomnia, heart arrhythmias, and gastrointestinal disturbances are often overlooked.

Drug Combinations

A particularly dangerous, and not uncommon, practice is combining alcohol with drugs or combining multiple drugs. The practice ranges from the coadministration of legal drugs such as alcohol and nicotine, to the dangerous random mixing of prescription drugs, to the deadly combination of heroin or cocaine with fentanyl (an opioid pain medication). Whatever the context, it is critical to realize that because of drug–drug interactions, such practices often pose significantly higher risks than the individual risks of the already harmful drugs.

Monitoring incidence and prevalence

In the United States, data on drug use and problems are collected from various sources. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (https://nsduhweb.rti.org/RespWeb/homepage2.cfm) provides national-level and state-level estimates of drug use (including nonmedical use of prescription drugs) and alcohol use as well as patterns and consequences of drug use in the general U.S. civilian population aged 12 years and older. Scientific random samples of households are selected across the United States, and the data from these surveys provide current, relevant information on drug use in the country. (See other secondary resources in this text’s website). In addition, major epidemiological studies such as the National Comorbidity Studies and the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, find consistent comorbidity patterns of SUDs with other psychiatric disorders in the U.S. civilian, noninstitutionalized population aged 18 years and older (Compton et al, 2007; Kessler et al, 2005).

Two additional minority-specific psychiatric epidemiology studies conducted in the United States, using nationally representative samples, are the National Survey of African Americans (NSAA) and the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS). Disclosing the use of drugs is, understandably, a sensitive issue. Thus, every effort, including assurance of anonymity, is made to encourage honesty. Large surveys must rely on self-reported behaviors.

Prevalence of Drug Use and Drug-Related Problems

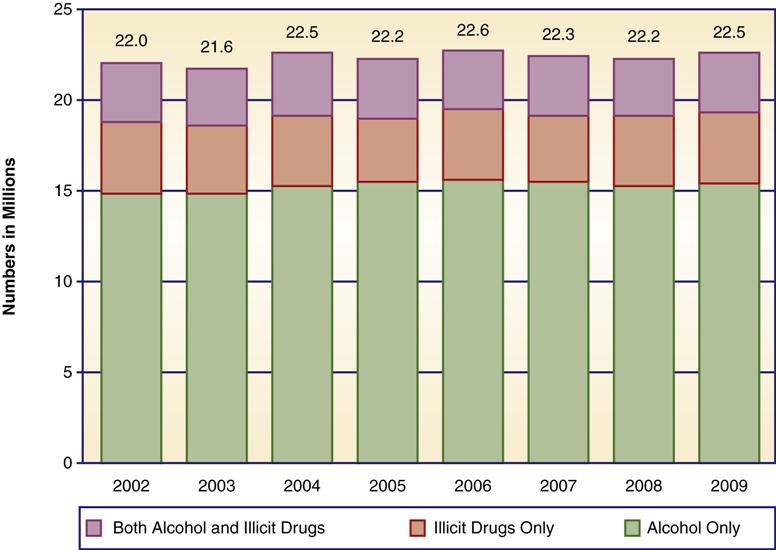

In 2009, an estimated 22.5 million persons (8.9% of the population aged 12 years or older) were classified with substance dependence or abuse in the past year based on DSM-IV-TR criteria (Figure 25-2). Of these, 3.2 million were classified with dependence on or abuse of both alcohol and illicit drugs, 3.9 million were dependent on or abused illicit drugs but not alcohol, and 15.4 million were dependent on or abused alcohol but not illicit drugs (SAMHSA, 2010).

Of nearly 4.6 million drug-related emergency department (ED) visits, half were attributed to adverse reactions to pharmaceuticals, and almost one-half (45.1%, or 2.1 million) were attributed to drug misuse or abuse. ED visits involving misuse or abuse of pharmaceuticals increased by 98.4% between 2004 and 2009, from 627,291 visits in 2004 to1,244,679 visits in 2009 (SAMHSA [DAWN], 2010).

Demographic Distribution of Substance Use and Abuse

Distribution of Alcohol Use

According to the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health NSDUH (SAMHSA, 2010), of Americans aged 12 years or older, 51.9% (more than 130 million people) are current drinkers of alcohol (consumed at least one drink in the past 30 days). Of Americans aged 12 years or older, nearly one-quarter (23.7%, or almost 60 million people) participated in binge drinking (five or more drinks on the same occasion) at least once in the 30 days prior to the survey, and 6.8% (more than 17 million people) reported heavy drinking (five or more drinks on the same occasion, on 5 or more days in the past month).

Rates of alcohol use vary by age; 3.5% among persons aged 12 to 13 years; 13% among those aged 14 to 15 years; 26.3% among those aged 16 to 17 years; 49.7% among those aged 18 to 20 years; and 70.2% among those aged 21 to 25 years. Underage drinking is particularly problematic for many reasons. An estimated 6.3% of 16- to 17-year-olds and 16.6% of 18- to 20-year-olds report driving under the influence (DUI) of alcohol in the past year, but the rate is higher for persons aged 21 to 25 years (24.8%).

Among older age groups, the prevalence of current alcohol use decreases with increasing age, from 66.4% among 26- to 29-year-olds, to 50.3% among 60- to 64-year-olds, and 39.1% among those aged 65 years or older (SAMHSA, 2010).

More males drink (57.6%) compared with females (46.5%), but among younger current drinkers aged 12 to 17 years, the rates are more similar (15.1% for males, 14.3% for females). Males aged 12 to 20 years report more current, binge drinking and heavy alcohol use (28.5%, 20.5%, and 7%, respectively) compared with females in that age group (25.8%, 15.5%, and 3.7%).

Whites are more likely than any other racial or ethnic group to report current use of alcohol (56.7%), compared with 47.6% for persons reporting two or more races, 42.8% for African Americans, 41.7% for Hispanic Americans, 37.6% for Asian Americans, and 37.1% for American Indians or Alaska Natives. Binge drinking was lowest among Asian Americans (11.1%), and highest among whites and Hispanic Americans (24.8% and 25%, respectively), with African Americans, American Indians/Alaska Natives, and individuals reporting two or more races falling in the middle (19.8%, 22.2%, and 24.1%, respectively) (SAMHSA, 2010).

Distribution of Tobacco Use

Annually, tobacco use results in more deaths (443,000 per year) compared with deaths from AIDS, unintentional injuries, suicide, homicide, and alcohol and drug use combined (SAMHSA, 2010).

The rate of current use of any tobacco product among persons aged 12 years or older remained steady from 2008 to 2009 (28.4% and 27.7%, respectively). Young adults aged 18 to 25 years had the highest rate of current use of a tobacco product (41.6%) compared with youth aged 12 to 17 years and adults aged 26 years or older (11.6% and 27.3%, respectively). Between 2002 and 2009, there was a significant decrease in the rates of current use of tobacco products and cigarettes among young adults; in 2002, the rates were 45.3% and 40.8%, respectively. The percentage of cigarette smokers among 12- and 13-year-olds also dropped from 2.1% in 2008 to 1.4% in 2009. About one-fifth (20.4%) of persons aged 35 years or older in 2009 had smoked cigarettes in the past month.

Current use of a tobacco product among persons aged 12 years or older was reported by a higher percentage of males (33.5% and females 22.2%). Among 12- to 17-year-olds, the rate was slightly higher for males, but the difference was not statistically significant.

In 2009, the prevalence of current use of a tobacco product among persons aged 12 years or older was 11.9% for Asian Americans, 23.2% for Hispanic Americans, 26.5% for African Americans, 29.6% for whites, 36.6% for persons who reported two or more races, and 41.8% for American Indians or Alaska Natives. After increasing from 0.7% in 2007 to 1.4% in 2008, use of smokeless tobacco in the past month among African Americans decreased to 0.9% in 2009.

As observed from 2002 onward, cigarette smoking in the past month was less prevalent among adults who were college graduates compared with those with less education. Among adults aged 18 years or older, current cigarette use in 2009 was reported by 35.4% of those who had not completed high school, 30% of high school graduates who did not attend college, 25.4% of persons with some college, and 13.1% of college graduates (SAMSHA, 2010).

Distribution of Illicit Drug Use

The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) obtains information on the use of illicit drugs, including marijuana/hashish, powdered and crack cocaine, heroin, hallucinogens (including among others, LSD, phencyclidine [PCP], mushrooms and MDMA or “Ecstasy”), and inhalants (such as nitrous oxide, amyl nitrite, gasoline, and various other cleaning fluids, and solvents). The NSDUH also collects information on the nonmedical use of prescription-type pain relievers, tranquilizers, stimulants, and sedatives, including drugs which are, or have been, available by prescription, as well as those which may be manufactured and distributed illegally, such as the stimulant methamphetamine.

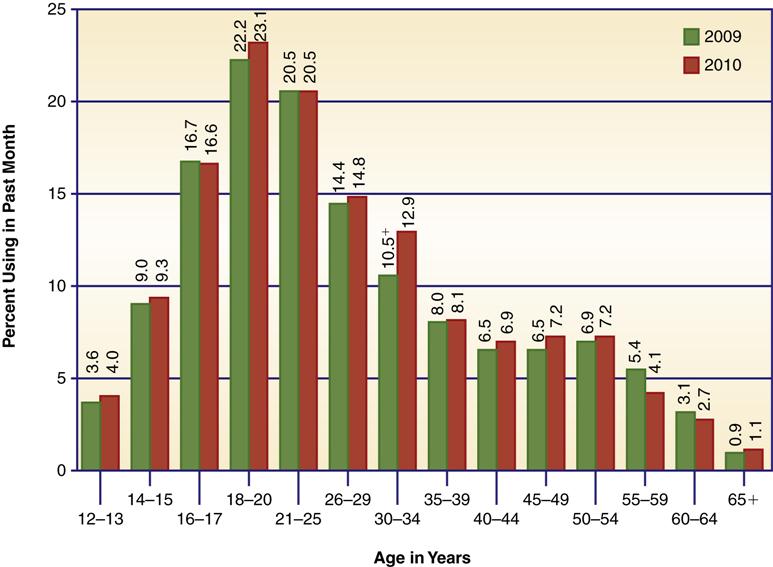

In 2009, an estimated 8.7% of the population aged 12 years or older (21.8 million Americans) were current (past month) illicit drug users, which represents an increase from 8% in 2008 and 7.9% in 2004 (SAMHSA, 2010). Illicit drug use was most prevalent among those 18 to 20 years of age (Figure 25-3). Marijuana was the most commonly used illicit drug (76.6%, or 16.7 million past month users). Of illicit drug users over age 12 years, 58% used only marijuana.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree